There is no clear consensus on the optimal treatment of patients with nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO) following failed nasolacrimal duct probing. Clinicians currently choose between repeat nasolacrimal duct probing, intubation of the nasolacrimal duct, balloon catheter dilation, dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) or a combination of procedures. Many surgeons perform intubation or balloon catheter dilation at the time of the initial procedure. Some clinicians base their treatment decisions on patient age since some studies have reported lower success rates in older patients.1,2

Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO) is relatively common among young children. Many cases resolve spontaneously or with lacrimal sac massage. Unresolved NLDO is often successfully treated with nasolacrimal duct probing performed in infancy or early childhood either in the office with topical anesthesia and physical restraint or under general anesthesia in a surgical facility. However, the optimal timing and setting for the procedure is not known. Resolution of symptoms is achieved in the majority of cases, although around 20percent of children have persistent NLDO symptoms following initial probing.3

Repeat probing

One of the tactics clinicians sometimes adopt after failed NLDO is performing repeat probing. The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group (PEDIG) reported successful resolution of symptoms in 56 percent of children under four years after repeat probing in a prospective, multi-center study.4 This was similar to previously reported success rates.

Repeat probing with intubation

Repeat probing with intubation of the lacrimal drainage system, another option after failed NLDO, can be performed via a monocanalicular or bicanalicular approach. The two approaches may be equally efficacious, and there is no consensus as to which technique is superior. 5,6 There are multiple materials available for each approach.

Monocanalicular stenting intubation has the advantages of quicker placement, ease of removal at home with dislodgement and easier removal in the office. Another recent PEDIG study suggests that for optimal results the stent should remain in place for at least two to five months.7 Another study showed no significant difference between results with two or five months' duration of intubation.8 Double bicanalicular stenting has been suggested in order to avoid the need for DCR in recalcitrant cases.9

Balloon catheter dacryoplasty

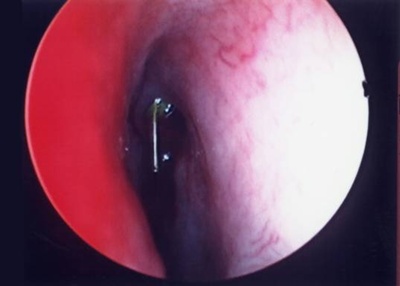

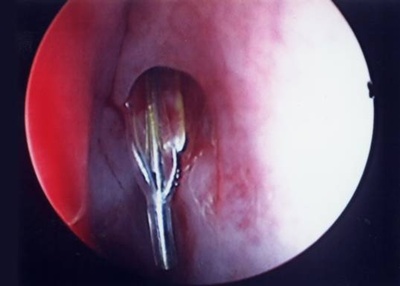

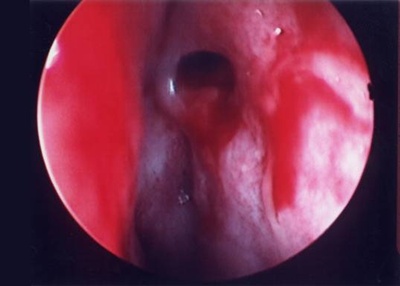

Balloon catheter dilation of the nasolacrimal duct, with or without subsequent stent placement, is another viable option. The procedure involves passing a balloon catheter through the nasolacrimal duct in a manner similar to traditional probing (Figure 1). The catheter remains in the duct while a series of dilations are performed via inflation and deflation of the balloon. (The catheter tip is shown deflated in Figure 2 and inflated in Figure 3). The resulting dilation of the valve of Hasner at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figures 4A, B, C and D

The fact that there is no requirement for subsequent tube removal is a benefit, but the device used does incur additional cost. A PEDIG study found that 77 percent of nasolacrimal duct balloon catheter dilations were successful compared with 84 percent of intubations after previous failed primary probing,7 and concluded that either choice was appropriate. Another study found modestly higher rates of success for both procedures,6 similarly concluding that there was no significant difference between the procedures.

Inferior turbinate infracture

Infracture of the inferior turbinate at the time of nasolacrimal duct probing has been reported to increase success in difficult cases.10 The infracture technique is performed by using a straight hemostat to grasp the inferior turbinate and rotate it 90 degrees medially. However, a more recent review in the European literature revealed no significant difference in efficacy between probing with or without infracture.11

Nasal endoscopy

Concurrent nasal endoscopy may be a helpful modality to identify nasal anatomic abnormalities that contribute to persistent nasolacrimal duct obstructions in difficult cases.12 This procedure typically requires the presence of a skilled otolaryngologist or oculoplastic surgeon. However, even when known anatomic anomalies are corrected surgically, nasal endoscopic assistance has not been proven to be more effective than standard probing and intubation techniques.13

Additional options

Successful resolution of NLDO symptoms can be achieved with the procedures discussed in the vast majority of cases, even after a failed initial probing procedure. If these more straightforward interventions fail, a DCR via either an external or endoscopic approach or a conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy (CDCR) with Jones tube may be considered (depending on clinical findings and patency of the canalicular system). Additionally, a new technique that may prove beneficial is a balloon catheter dilation-assisted DCR performed via nasal endoscopy without a concurrent skin incision.

References

- Kashkouli MB, Kassaee A, Tabatabaee Z. Initial nasolacrimal duct probing in children under 5: cure rate and factors affecting success. J AAPOS. 2002;6(6):360-363.

- Paul TO, Shepherd R. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: natural history and the timing of optimal intervention. J AAPOS. 1994;31(6):362-367.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, Repka MX, Chandler DL, et al. Primary treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction with probing in children younger than 4 years. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(3):577-584.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, Repka MX, Chandler DL, et al. Repeat probing for treatment of persistent nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2009;13(3):306-307.

- Ostrow G, Iyengar SE, Olitsky SE, Stass-Isern M, Hug D, Smith LP. Monocanalicular versus bicanalicular silicone tube intubation for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2007;11(1):100.

- Goldstein SM, Goldstein JB, Katowitz JA. Comparison of monocanalicular stenting and balloon dacryoplasty in secondary treatment of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction after failed primary probing. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20(5)352-357.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, Repka MX, Chandler DL, et al. Balloon catheter dilation and nasolacrimal duct intubation for treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction after failed probing. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(5):633-639.

- Kominek P, Cervenka S, Matousek P. Does the length of intubation affect the success of treatment for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction? Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(2):103-105.

- Mauffray RO, Hassan AS, Elner VM. Double silicone intubation as treatment for persistent congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophth Plast Reconst Surg. 2004;20(1):44-49.

- Wesley RE. Inferior turbinate fracture in the treatment of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction and congenital nasolacrimal duct anomaly. Ophthalmic Surg. 1985;16(6):368-371.

- Attarzadeh A, Sajjadi M, Owji N, Reza TM, Farvardin M, Attarzadeh A. Inferior turbinate fracture and congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16(4):520-524.

- Kouri AS, Tsakanikos M, Linardos E, Nikolaidou G, Psarommatis I. Results of endoscopic assisted probing for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction in older children. Int J Ped Otorhinolarygol. 2008;72(6):891-896.

- Gardiner JA, Forte V, Pashby RC, Levin AV. The role of nasal endoscopy in repeat pediatric nasolacrimal duct probings. J AAPOS. 2001;5(3):148-152.