When you visit the eye doctor for a checkup, you may be asked to read an eye chart. The chart measures your visual acuity, or sharpness of vision. If you don’t wear glasses or contacts, your eye doctor will use the results to find out whether you need them. If you wear corrective lenses, the results will show if your prescription needs to change.

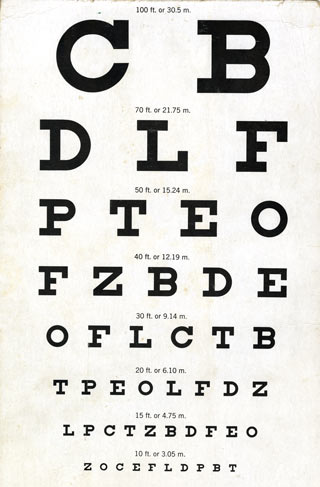

A standard Snellen vision testing chart from the 1950s.

Are All Eye Charts the Same?

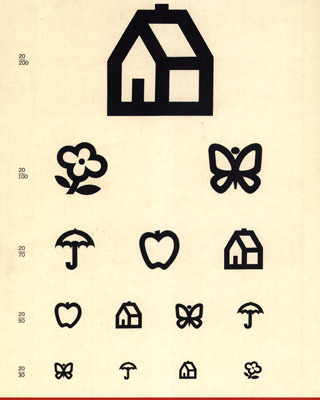

Various types of eye charts are available. Some charts use pictures or patterns, while others use letters. Eye care providers might use certain charts for measuring distance vision and others for measuring near vision. Some eye charts are especially for children while others work for both children and adults. The Snellen eye chart, however, is the most common and the most recognizable.

How To Use the Snellen Eye Chart

The Snellen chart usually shows 11 rows of capital letters. The first line has one very large letter. Each row after that has increasing numbers of letters that are smaller in size.

You stand 20 feet away from the Snellen chart, and read from it without your glasses or contacts. You cover one eye and read out the smallest line of letters you can see. Then you cover the other eye and do it again. In some offices, you view the chart through a mirror. This means the test can be done with less than 20 feet of space. The results are the same whether or not a mirror is used.

If you have 20/20 vision, you have normal visual acuity.

The top number refers to the distance in feet that you stand from the chart. The bottom number is the distance at which a person with normal sight can read the same line you correctly read. A person with 20/20 vision can see what an average person can see on an eye chart when they are standing 20 feet away.

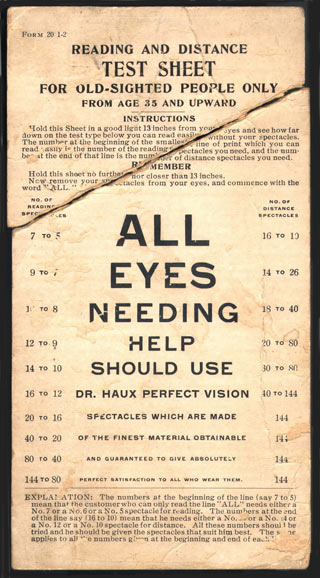

A travelling salesman's vision testing pocket card from the 1910s.

History of the Snellen Eye Chart

Dutch eye doctor Hermann Snellen developed the Snellen eye chart in the 1860s. He was a colleague of Dr. Franciscus Donders. Donders diagnosed vision problems by asking people to look at a chart on a wall and tell him what they could see. According to The New York Times, he asked Dr. Snellen to make the chart.

Dr. Snellen also created a chart called the “Tumbling E” eye chart. People who cannot read and young children who don’t know the alphabet can use it. Instead of using different letters, this chart uses a capital letter E that faces in different directions. The person being tested uses their fingers to show the direction in which the “fingers” of the E are pointing.

A vision testing chart using simple pictures of houses, flowers and other objects. These kinds of charts can be used with young children or people who cannot read.

“Before Dr. Snellen created the standardized eye chart, each ophthalmologist or oculist had a chart they preferred,” says Jenny E. Benjamin, MA, Director of the Truhlsen-Marmor Museum of the Eye. “The Snellen eye chart allowed a person to go from any eye care provider to any eyeglass maker and get the same results.”

The eye chart came along during a time of rapid industrialization. People needed good eyesight for many jobs, from railroad engineers to factory workers, Benjamin says.

When Should You Get an Eye Exam?

Your visual acuity is measured as part of an eye exam. The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends that you get a baseline eye examination at age 40. This is when early signs of disease or changes in vision may happen. Eye charts do not help the eye doctor tell whether you have an eye disease such as glaucoma or a problem with your retina. They also do not measure other vision problems such as loss of peripheral (side) vision.