This article is from January 2007 and may contain outdated material.

In 2005, more than 2.8 million cataract surgeries were performed in the United States, a rate of nearly 7,700 per day. Until recently, this procedure was considered successful when postoperative patients achieved a Snellen visual acuity score of 20/40 or better. However, what were once considered good results are no longer regarded as optimal and are currently being redefined: Quality of vision as measured by contrast sensitivity—which was previously given little attention—has now become an important factor in the detection of postoperative complications of cataract surgery.

|

Could Have Been Prevented?

|

|

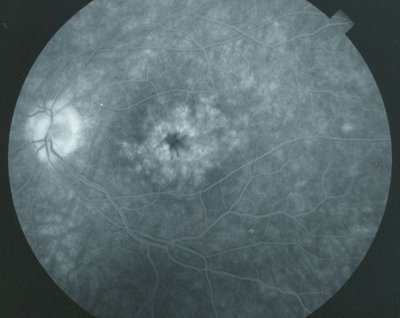

| Cystoid macular edema. |

Insidious CME. Cystoid macular edema is the most common cause of decreased vision in patients following cataract surgery, occurring much more frequently than either retinal detachment or endophthalmitis. Although CME was clinically recognized and described over 50 years ago, much remains unknown about it. Even the rate of occurrence is uncertain, with estimates ranging from 1 to 19 percent. But it could be much higher. “If you just look at macular thickness as observed in ocular coherence tomography, the incidence of CME may be as high as 60 to 70 percent,” said Eric D. Donnenfeld, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology, New York University. Moreover, “all patients who have increases in macular thickness as measured by OCT will show some decrease in quality of vision as measured by contrast sensitivity,” said Calvin W. Roberts, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology, Cornell University.

“Increased patient expectations and increased quality of vision issues have dictated that measures we used in the past, such as Snellen visual acuity, were really inadequate to describe the visual loss associated with CME,” said Dr. Donnenfeld. David S. Rho, MD, clinical associate professor of ophthalmology, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, explained: “I think we’re realizing that there are more subtle ways in which patients will complain about their vision when they, in fact, have bona fide CME. For example, subtle contrast sensitivity deficits, reading speed deficits or color deficits may indeed be part of a patient’s subjective appraisal that they are not seeing properly after cataract surgery. And yet they may test at 20/20 on the Snellen chart. This suggests that there’s more to it than just Snellen visual acuity.”

Looking for, Even Preventing, CME

There have also been shifts in case management paradigms as new data emerge about controlling the development of CME. Unless a patient presented with risk factors for developing CME—diabetes, previous vein occlusions, uveitis or epiretinal membrane, for example—prophylactic intervention prior to cataract surgery has not been traditionally indicated. Similarly, unless a patient was symptomatic, or CME was suspected, ophthalmologists did not generally test for CME, and yet it may not be symptomatically perceptible to patients and physicians without diagnostic testing.

Herein lies the problem: “The longer CME exists, the more permanent damage occurs in the retinal architecture. If you can catch CME early and treat it, you can get a nice resolution of the problem. Once CME becomes chronic, there is permanent damage to the retinal architecture and loss of quality of vision,” said Dr. Donnenfeld.

“The edema has a small but lasting effect, which makes the argument for prevention more compelling,” Dr. Roberts said. “If ophthalmologists pre-treat patients with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the inflammatory cascade of prostaglandins is interrupted, which fosters less inflammation and less CME.” Dr. Roberts coauthored a study presented at the 2006 Joint AAO/APAO Meeting in November that compared the use of pre- and postop ketorolac (Acular) plus postop steroid treatment with steroid treatment alone in cataract surgery. When final visual acuity, OCT changes and contrast sensitivity were compared in the two groups, the patients on ketorolac exhibited significantly less retinal thickening and a lower incidence of CME.1

Options Now in the Running

There are several NSAIDs being studied for the management of CME, although the jury is still out on which one is safest or most effective.

At the 2006 Association for Research Vision and Ophthalmology Annual Meeting, Dr. Rho presented findings from his study comparing bromfenac (Xibrom), diclofenac (Voltaren) and ketorolac for the treatment of post-cataract CME. He found that bromfenac dosed twice daily was as efficacious as either diclofenac or ketorolac dosed four times per day.2 “The data indicate that for the 85 patients currently enrolled in the study, for the bromfenac treatment group, the average letters gained on the ETDRS chart was 15.1. For diclofenac it was 10.9 and for ketorolac it was 11.1. As such, the data demonstrated a strong trend toward superiority of bromfenac over diclofenac or ketorolac,” Dr Rho said.

Adversity and adherence. Dr. Rho also found a difference in terms of the perceived burning and stinging associated with bromfenac, when compared with ketorolac and diclofenac. “It’s much better tolerated in terms of comfort,” he said. Further, he said, the easier dosing of bromfenac may result in increased patient adherence. “We’ve learned that the less frequently you dose a medication, the more likely that the patient will adhere to a prescribed regimen. Even if bromfenac ultimately is found to be equally efficacious as ketorolac or diclofenac, the two advantages of BID dosing and enhanced comfort are noteworthy.”

“The prophylactic use of NSAIDs is an important part of maximizing our outcomes,” said Dr. Roberts. “We’re implanting more and more multifocal IOLs. By design alone, contrast sensitivity will decrease. The use of this type of lens requires that the macula be in tip-top shape to achieve the full benefits of surgery. These patients, in particular, need NSAIDs to appreciate the full benefit of the lenses.”

Cost Effectiveness of Prophylaxis?

Is it cost-effective to pursue treatment that may not be necessary for most patients? “You have to factor in the cost of the NSAID vs. the costs incurred by sending some patients for a retinal referral, fluorescein angiogram, OCT, chronic medications or recurrent visits,” said Dr. Donnenfeld. “There’s a big savings to society by using a NSAID because you cut down on the inherent costs of managing a case of CME after surgery. That’s in addition to quality of vision issues.”

Established standards of care and community practice are not always in step with each other. But Dennis M. Marcus, MD, noted that “The results of recent studies demonstrating decreased macular thickness with prophylactic NSAIDS prior to cataract extraction are compelling. While the absolute impact on patients’ objective and subjective visual functioning has not been definitive, routine NSAID use for CME prophylaxis is a reasonable approach.” Dr. Marcus is a professor of clinical ophthalmology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C.

And not only that, but . . . Dr. Donnenfeld said the use of NSAIDs also has underlying advantages, such as preventing pupillary miosis. “When you operate on someone with smaller pupils it takes longer to complete the surgery. So, by having maximal dilation, which is achieved with an NSAID, you operate faster as well. In addition to the obvious cost benefits of operating faster, there is a theory that the less time you spend operating on an eye, the less risk there is of developing CME, because there’s less invasive time in the eye and less damage to the structures. It’s very rare in ophthalmology where we can get better outcomes for both the surgeon and patient and it ends up costing less as well.”

Dr. Roberts seconded those ideas. “The history of cataract surgery is a history of small, incremental improvements. Singly, these improvements mean little, but together they give us the magnificent surgery we have today. The use of an NSAID to reduce postoperative macular edema is just another surgical tool to improve outcomes. In fact, it is fair to ask: Why implant a high-technology IOL if you are not also going to take the steps to preserve the macula so that the patient retains the physiological capacity to appreciate the image the lens can produce?”

___________________________

1 Wittpenn Jr, J. R. et al. A masked comparison of Acular LS plus steroid vs. steroid alone for the prevention of macular leakage in cataract patients; Nov. 10–Nov. 14, 2006, Las Vegas, Nev.

2 Rho, D. S. et al. Bromfenac 0.09% versus diclofenac sodium 0.1% versus ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% in the treatment of acute pseudophakic cystoid macular edema; April 30–May 4, 2006; Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

___________________________

Dr. Donnenfeld is a consultant to Allergan and Alcon, and has received research support from Allergan, Alcon and Ista. Dr. Marcus reports no related interests. Dr. Rho is a consultant to Ista. Dr. Roberts is a consultant to Allergan.