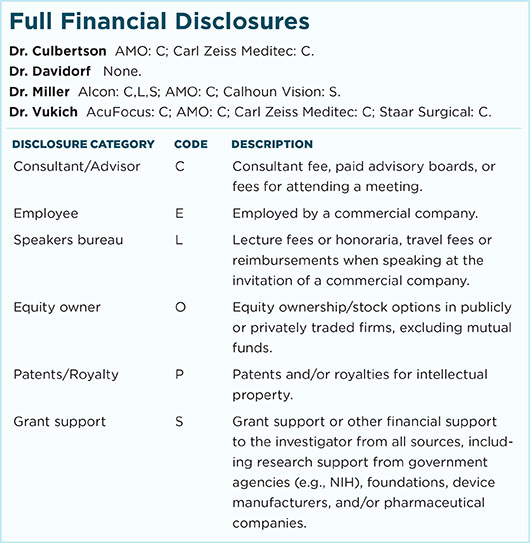

By Kevin M. Miller, MD, with William W. Culbertson, MD, and John A. Vukich, MD

Download PDF

Although debate continues on the value of femtosecond laser–assisted cataract surgery (FLACS), many ophthalmologists are currently using the technology, and others are interested in learning how it might fit into their practices. Here, Kevin M. Miller, MD, of UCLA’s Stein Eye Institute, hosts a roundtable with 2 other surgeons who regularly perform FLACS: William W. Culbertson, MD, of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, and John A. Vukich, MD, of the University of Wisconsin Medical School in Madison. Drawing on personal experience, the trio provide their perspectives and clinical insights on the technique. (Note: Dr. Miller uses the Alcon LenSx laser, Dr. Culbertson predominantly uses the AMO Catalys laser but also the Alcon LenSx, and Dr. Vukich uses the AMO Catalys.)

Femto in the Practice

Dr. Miller: Why have you chosen to add FLACS to your practice? Is FLACS better than traditional cataract surgery?

Dr. Culbertson: Well, the literature is a little bit at odds, with some articles showing some benefit and others not showing any benefit. In my practice, it is beneficial for simplifying the act of removing the cataract and for correcting corneal astigmatism with both anterior penetrating relaxing incisions and intrastromal relaxing incisions.

In dealing with both our faculty and our trainees, it’s been my experience that the surgery simplifies and automates many of the more difficult parts of the procedure, such as making a capsulotomy and chopping and emulsifying the lens. I think it makes the procedure more straightforward; and, in my hands, it leads to fewer complications.

Dr. Vukich: It’s difficult to say what’s better. FLACS introduces another step, and instrument, into the process, and it involves additional time as well. As a practical matter, each step that the laser does for the surgeon is something that surgeons can do themselves. For example, capsulotomies, while not perfect when done manually, don’t cause surgeons a great deal of difficulty. The challenge is making them consistently the right size, the right shape, and in the right location—and the laser does that far better than we can do by hand.

For more difficult lenses—those that have weak zonules, milky white lenses in which there is pseudoexfoliation—it does a very good job of 1) creating a capsulotomy, and 2) softening the lens and diminishing the amount of phaco time. There are benefits to introducing less energy into the eye and diminishing the phaco time.

I think you have to look at it in total and ask whether having additional steps (docking the laser, doing the measurements, and performing the lasing part of the surgery) balances out to create a better procedure. For many of us who are used to it, the answer is yes. But with each step, there’s room for argument to say, “Well, I can do each one of those steps anyway. I’m not sure that, in total, it makes sense.” And I think that’s why we’re having this debate. There’s clearly a path forward with technology, and femtosecond laser is an important step, but we have to maximize its use as well.

|

|

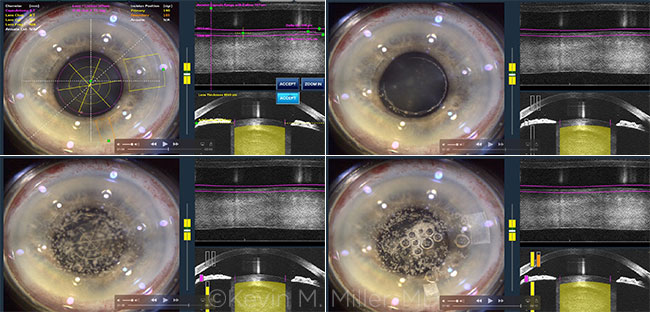

FEMTO. Four images, taken in sequence, of an eye undergoing FLACS on an Alcon LenSx laser.

|

Clinical Relevance

Dr. Miller: Are the benefits that we’ve described—a more circular and central capsulorrhexis, reduced energy dissipated into the eye, maybe nicer-looking relaxing incisions—clinically relevant, or are they just artistic?

Dr. Vukich: Artistically, [a femtosecond capsulotomy] is beautiful to look at, and it eliminates the issue about overlap of the optic or optic capture; so, in specific circumstances, the aesthetics do count for something. You also get a more controlled healing response in terms of capsular fibrosis over time, and you can maintain better centration of the IOL. I believe that those are real benefits, and I find this appealing about the technology.

Dr. Culbertson: We have always assumed that various parts of cataract surgery, such as phacoemulsification, removal of the individual nuclear fragments, chopping and segmentation of the fragments, etc., sometimes take considerable energy, have sudden fallout for the endothelium and iris and inflammation, and create some hazard for the capsule. And you can say, “Well, if we can make these things much more straightforward, reduce phaco energy, and reduce the maneuvers that we make to remove the nucleus, that must count for something.”

People who have used this technology feel that it does make a difference with the surgery and that it should make a difference with the outcomes as well.

Dr. Vukich: We haven’t been able to demonstrate a significant improvement in the outcomes, however, and that’s one of the things that leads to debate. Yes, we may be doing individual steps better, but what we are trying to do in the end is get a better visual outcome and achieve the refractive correction we intended. What is important to patients is not necessarily how the cataract is removed but rather how they see afterward. To that extent, it’s difficult to tease out a difference in our attempt to achieve the results of our IOL calculations. And that’s what many of us struggle with.

Risks

Dr. Miller: What do you tell patients about the risks of FLACS, if any?

Dr. Culbertson: I don’t elaborate on the risks in that I feel they are nominal compared with the risk of cataract surgery in general. Any added risk of the laser is outweighed by the benefits of the pretreated lens, pretreated capsulotomy, reduced complications (in my experience), etc.

What are the added risks of using a laser? They are rare, such as displacement of the interface during the lasing and subsequent “treatment” of the cornea, so-called radial tears, an incomplete capsulotomy, the laser cutting through the posterior capsule, or added pressure of the gas breaking out the posterior capsule. But those are very uncommon.

Dr. Miller: Dr. Vukich, do you have a different or similar approach?

Dr. Vukich: An identical approach. I talk about the risk of cataract surgery, but I don’t break it down into the elements of the cataract surgery. Similarly, I don’t talk about the risks of an IOL. Certainly, there are things that can be displaced, and there are other issues, and you could talk about the elements of the surgery and say, “Each one of these has a risk”—but that becomes confusing to the patient. Instead, we talk about the risk of the surgery as a whole. But I certainly agree with Dr. Culbertson that the added risk of the FLACS procedure is nominal at best, and it doesn’t add risk in terms of the overall surgery.

Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

Dr. Miller: Do you mention the likelihood that patients will have a subconjunctival hemorrhage—because that does make FLACS different from conventional phaco?

Dr. Vukich: I don’t mention that, but we do mention that during routine cataract surgery it’s not uncommon for there to be small subconjunctival hemorrhages either from grasping with a .12 forceps at the level of the conjunctiva or when making the incision—sometimes there can be bleeding from limbal vessels. That’s not an uncommon finding, so I don’t necessarily attribute it to the laser itself, other than to say that there could be some redness associated with the surgery that will heal and go away with time.

Dr. Culbertson: I don’t really single out the subconjunctival hemorrhage. I always talk to patients about the major risks of surgery such as infection, hemorrhage, retinal detachment, etc. All the companies have improved their patient interfaces and their docking to the eye so that the problem of subconjunctival hemorrhages is relatively rare now. Actually, if the upper lid comes down to the upper limbus and the lower lid comes up to the lower limbus, it’s hardly visible except in a very exceptional case.

More at the Meeting

Cataract Monday takes place Oct. 17 and features the following:

- Spotlight on Cataract: Complicated Phaco Cases—My Top 5 Pearls (Spo2), 8:15 a.m.-12:15 p.m.

- Novel Technology in 2016—What’s Available Around the World (but not in the United States) (Sym40), 2:00-4:00 p.m.

Find more cataract events with www.aao.org/programsearch. |

“Is FLACS Best for Me?”

Dr. Miller: This question comes in various forms, but a patient might ask, “Is FLACS better than conventional surgery?” or “Would you recommend the laser for me?”

Dr. Vukich: That’s a common question. I think people are enamored with the concept of laser. In fact, even before we had FLACS, there were patients who believed that ultrasound was laser based. They really don’t understand necessarily what they’re asking, but they want the best technology. They want the latest. So, when they ask, “Is it better than conventional cataract surgery?” my answer is that it adds to the consistency of the procedure. I think that this added element of technology makes what I do reproducible, and that is better by definition.

Is it a necessary component? I think that’s where we have to be careful to explain that if, for some reason, we can’t use the laser—we can’t dock it or the pupil is too small, or some other issue—that they’re not getting second best. It’s important for the patient to know that I’m going to use the best technology to provide the best outcome, and I’ll only use it if I believe it is safe and it’s going to work well in their specific instance.

Dr. Culbertson: I tell patients that I think that for the average cataract—that is, a grade 2 nuclear cataract in a patient with no clinically significant astigmatism or other issues—the benefits are marginal. In fact, just as John alluded to, many patients come asking for laser cataract surgery. They’ve heard about it on the Internet, and they come ready to have it. For every one of those patients who are not receiving a premium IOL, do not need a relaxing incision to treat their astigmatism, or do not have an intraocular problem such as endothelial dystrophy or loose zonules, I tell them they don’t need it. In fact, I spend more time talking patients out of it than I do talking patients into it. Often, it’s quite a process to have them understand that, for them, it would be of marginal clinical significance to have the laser.

Dr. Miller: I will often tell patients, “I like the incisions that the laser makes. They look beautiful under the slit lamp. Unfortunately, I get to see that, you don’t, and it doesn’t really make much difference in your final visual outcome.” But some patients want to know that they have a sweet-looking incision.

I also tell them that we’re in the early stages of laser adoption. It’s kind of like in the early days of phaco: When we had to open up our 3-mm phaco incision to a 7-mm incision to accommodate a nonfolding PMMA lens, phaco didn’t make a whole lot of sense. Then foldable lenses came along, and suddenly there was a compelling reason to use phaco to remove the cataract. We need a compelling reason to use the femtosecond laser, and that will probably come with new lens designs—perhaps where you can incorporate the anterior capsule in some sort of groove. We haven’t gotten to that stage, but I think it will come.

___________________________

Dr. Culbertson is professor of ophthalmology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, Fla. Relevant financial disclosures: AMO: C; Carl Zeiss Meditec: C.

Dr. Miller is professor of ophthalmology at the UCLA Stein Eye Institute in California. Relevant financial disclosures: Alcon: C,L,S; AMO: C.

Dr. Vukich is associate clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Wisconsin Medical School in Madison. He is also the surgical director of the Davis Duehr Dean Center for Refractive Surgery in Madison. Relevant financial disclosures: AMO: C; Carl Zeiss Meditec: C.

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.

A Case for Phaco

The MD Roundtable above is one part of a larger discussion about FLACS. In fact, some cataract surgeons are unenthusiastic about the femtosecond laser for cataract surgery in its current state of development. Among them is Jonathan M. Davidorf, MD, assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at Stein Eye Institute in Los Angeles, who cited some recent studies and clinical observations to inform his position.

The literature. While some studies support the use of femtosecond laser in cataract surgery, others question the benefit of this technology. Some of Dr. Davidorf’s concerns are supported by some recent studies.

Visual outcomes. Ewe et al. assessed the visual outcomes of 988 eyes that underwent FLACS and 888 eyes that underwent standard phacoemulsification cataract surgery (PCS) in a prospective multicenter comparative case series. At 6 months postoperatively, the authors found no clinically meaningful visual benefit to femto surgery over standard phaco.1 Although best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was marginally better with FLACS than PCS (20/24.5 vs. 20/26.4), the letter gains achieved after surgery were greater in the phaco eyes, which had lower BCVA at baseline; and the percentage of eyes within 0.5 D of the preoperative aim refraction was higher in the PCS group (PCS, 82.6% vs. LCS, 72.2%; p < .0001). The authors concluded that, given the refractive outcomes, FLACS is not cost-effective at this time.

Safety. The study by Ewe et al. also looked at safety issues. The study found that the FLACS group had 15 anterior capsule tears (1.52%) compared with 3 (0.34%) in the phaco group (p = .0087) and 11 posterior capsule tears (1.11%) versus 2 (0.02%) in the phaco group (p = .024). “An anterior capsular tear rate of 1 to 2 per hundred cases would be totally unacceptable in my practice,” Dr. Davidorf said, “and a posterior capsular tear rate of 1% would be a disaster.” He noted that another study found similar results for anterior capsule tear (1.84%).2

Time considerations. Northwestern University researchers conducted a retrospective comparative case series to examine the impact on surgical times of the FLACS learning curve of one experienced anterior segment surgeon.3 Grewal and colleagues reviewed the surgeon’s first 200 FLACS cases and divided them into 5 sequential groups. From there, the authors examined times for various aspects of the procedure from femtosecond time (from application of the suction ring to removal of the suction ring) to total OR time (from the time that the patient was wheeled in to the OR to when he or she was wheeled out). As the surgeon and OR staff gained experience with FLACS, times shortened, sometimes significantly. However, when total OR times were compared with a control group of the surgeon’s phaco cases, the FLACS group’s time was 17.2% longer (p = .0001).

Cost considerations. The Northwestern study also discussed the impact of OR times on costs. According to the authors’ calculations, by the end of the study—when the surgeon and OR were most efficient—costs for FLACS, including OR fees and other costs driven by charges/minute, such as an anesthesia professional and other OR personnel costs, were approximately 45% greater than for phaco. “This study tells us what we already know,” said Dr. Davidorf. “That the cost of femtosecond cataract surgery far exceeds that of gold-standard phaco.”

A matter of observation. “Generally speaking, most cataract surgeons make a good capsulorrhexis without using a femtosecond laser,” said Dr. Davidorf. “If we as surgeons really believed that a perfectly centered, perfectly circular capsulotomy had any advantage on clinical outcomes compared with a slightly less-than-perfect capsulotomy, we would have been using, for years, an optical zone marker on the cornea as a guide to improve the consistency of our already excellent manual capsulotomies. Why is it that surgeons have rarely done this? Because we really believe that it doesn’t matter.”

Talking with patients. Considering that Dr. Davidorf doesn’t think that femtosecond laser is typically in his patients’ best interest, how does he handle patients who request laser surgery? He has a standard reply. “I will say, ‘Sure, we can do the laser, no problem. Or we can just use ultrasound.’ And the patients will say, ‘Wow, you can use ultrasound for my cataract surgery!’ They can’t believe it. They have positive associations with ultrasound because they know from their experiences—with prenatal ultrasound or other medical uses—that it doesn’t hurt, and they perceive it as a cool technology.”

___________________________

1 Ewe SYP et al. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(1):178-182.

2 Abell RG et al. J Cat Ref Surg. 2015;41(1):47-52.

3 Grewal DS et al. J Refract Surg. 2016;32(5):311-317.

___________________________

Dr. Davidorf is in private practice at the Davidorf Eye Group in Los Angeles and is assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at the UCLA School of Medicine, Stein Eye Institute. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

|