Download PDF

In a matter of weeks, lower vertebrates such as lizards and frogs can regenerate a lost limb or tail—fish can regrow an entire eye or even half a heart or brain. Now, U.S. and Chinese researchers have discovered a novel method to harness the regenerative potential of the human lens by using endogenous lens epithelial stem cells (LECs). Their method has been used to regrow a new, functioning lens in 24 eyes of 12 children under age 2 whose congenital cataracts were removed.1 Because the patient’s native LECs are used, this technique theoretically avoids the risks of infection, tumor formation, and immune rejection linked to pluripotent stem cells.

Standard procedures damage LECs. Early clues to this capability emerged from observing the unwanted aberrant lens regeneration that occurs after removal of congenital cataracts, said coauthor Kang Zhang, MD, PhD, chief of ophthalmic genetics at University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine. The standard capsulorrhexis and lensectomy procedure subjects these eyes to insults from large incisions, he said, and removes more than half of the lens stem cells, increasing the risk of scarring and inflammation. “Lacking the proper environment and support,” he said, “the remaining LECs randomly regenerate into disorganized lens tissue known as posterior capsular opacity, which requires a laser procedure to remove it and open the posterior capsule.”

New method spares LECs, allows regrowth. Dr. Zhang and colleagues developed and tested a minimally invasive method to remove the cataract while preserving the lens epithelial stem cells, first in rabbits and macaques and then in humans. It involved creating a 1.5-mm self-healing incision in the periphery of the anterior capsule—out of the visual axis—and removing the soft cataractous lens. “This preserved the integrity of the lens capsule and a sufficient number of stem cells to proliferate and differentiate into a new functioning lens, along with the support of growth factors,” said Dr. Zhang.

In the study, all 12 human infants regenerated a clear, biconvex, functioning lens at 3 months, and there was no sign of cloudiness or significant complications at 6 months. Refractive power increased significantly from the first week to 8 months after surgery, at which time the average central thickness of the regenerated lens was comparable to that of a native lens.

In comparison, 25 infants who had a large capsulorrhexis and standard surgery in both eyes experienced a higher incidence of postsurgical inflammation, early-onset ocular hypertension, and increased lens clouding. Moreover, removing the whole lens—a standard procedure for infants under age 2 with congenital cataracts—disrupts ocular development and puts the child in need of frequent refractions and at high risk for complications such as glaucoma.

Caveats and challenges. Dr. Zhang cautions that this preliminary research needs independent replication with larger numbers of patients and longer follow-up. In addition, he cannot exclude the possibility that the regenerated lens may become cloudy again. “If the cataract is caused by an inherited mutation, we have not solved the root problem,” he said.

Earlier research by Dr. Zhang and colleagues found that an endogenous molecule called lanosterol may prevent protein aggregation.2 He is optimistic that lanosterol might prove useful in the regenerated lens. “Regardless, keeping the lens clear for even a year or two buys an infant precious time for visual development,” he said, “and gives the ophthalmologist a chance to later insert an intraocular lens, if needed, during a preferable time.”

Future areas of research. The investigators are also turning their attention to age-related cataracts, looking for ways to overcome the reduced regenerative capacity in older adults, as well as to minimize damage to lens stem cells by using smaller incisions and lower-energy removal of cataracts.

—Annie Stuart

___________________________

1 Lin H et al. Nature. 2016;531(7594):323-328.

2 Zhao L et al. Nature. 2015;523(7562):607-611.

___________________________

Relevant financial disclosures: Dr. Zhang—None.

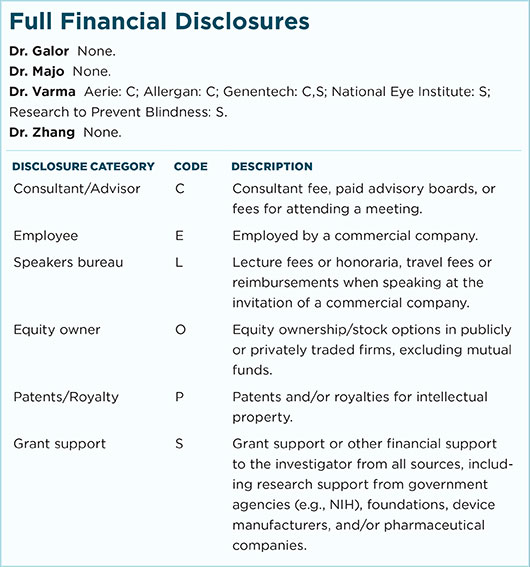

For full disclosures and disclosure key, see below.

More from this month’s News in Review