Download PDF

Several years ago, Thomas A. Oetting, MD, was performing cataract surgery with a resident at the University of Iowa, as he had done hundreds of times in his career. Toward the end of the case, the anterior chamber temporarily shallowed. Dr. Oetting asked the resident what conditions could lead to this finding, and “malignant glaucoma” aka aqueous misdirection was mentioned briefly.

The temporary shallowing turned out to be insignificant, and the surgery was completed uneventfully. But when the patient came in for his one-month postoperative visit, he asked Dr. Oetting to give it to him straight: “When are you going to tell me about my cancer?” The patient had heard the word “malignant” in the operating room and spent the month believing he had cancer.

“It was a compelling lesson on how important patient communication during cataract surgery can be,” said Dr. Oetting, “and how easy it is to forget, especially in a teaching environment, that the patient is listening.”

The Patient’s Experience

Given that cataract surgery is generally conducted while the patient is awake, it’s important to be aware of how intraoperative conditions and communication affect the patient’s experience and satisfaction. High levels of anxiety can lead to restlessness and interfere with cooperation, thus affecting outcomes as well.

Reinforcing the patient’s confidence in the surgical team is one of the best ways to minimize anxiety, according to Dr. Oetting. “It’s helpful to make sure everyone in the operating room is on the same page and following the same procedures. Everything should feel routine, without a lot of questions between staff members,” said Dr. Oetting. “That goes a long way toward promoting a sense of confidence.”

Steven I. Rosenfeld, MD, at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, uses intravenous midazolam whenever possible in addition to topical anesthesia with high-viscosity tetracaine and intracameral lidocaine to keep his patients calm and comfortable throughout the surgery. “My patients really appreciate it, and, in fact, look forward to it. They liken it to having all the benefits of being knocked out for a colonoscopy without the dreaded bowel prep the night before.”

Another option is preoperative oral sedatives. Dr. Oetting uses them at the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, where he is chief of the eye service, and reports excellent effects.

According to Bonnie A. Henderson, MD, at Tufts University, the amnesia related to intravenous midazolam makes patient communication all the more crucial. “Even if the surgery was performed flawlessly, the patient’s perception of the outcome may be colored by what he or she remembers from the surgery. Patients sometimes recall a few words that, when taken out of context, give them the wrong impression that something unexpected occurred. I frequently have patients suspiciously ask if I was even present during the procedure.”

Studies have identified several factors that influence a patient’s intraoperative experience: confidence, pain perception, comprehension, memory, reassurance, and satisfaction.1 Effective communication is a common denominator in addressing these issues. It begins with a clear informed consent discussion a week or so before surgery—one that reassures the patient but does not trivialize the procedure or minimize risk.

The Preop Counseling Challenge

“It’s the first time for them, but the ten thousandth time for you. Somehow, you have to muster enthusiasm for the preoperative discussion,” said Dr. Oetting. Trying to keep it fresh is not easy. Dr. Oetting often challenges himself to convey the most information possible in the fewest number of words that raise the fewest number of questions from the patient.

“Because we spend so much time during preop visits discussing the type of intraocular lens [IOL] and the logistics of the surgery and follow-up, we don’t tend to talk about the intraoperative experience,” said Dr. Rosenfeld. But the preoperative discussion is a valuable opportunity to set realistic patient expectations regarding discomfort, level of consciousness, visual sensations, and complications.2 Often this can make the patient more confident when he or she enters the operating room.

Dr. Oetting is always looking to improve his “script” with pithy lines. To help dispel misapprehensions about what conscious surgery may be like, for example, he tells patients that most people find the removal of the drape at the end to be the worst part, as it may be moist and stick to the face a little. “That’s something everyone can relate to and isn’t a big deal. It goes a long way toward allaying fears of what kind of discomfort the patient worries he or she might be in for.”

When Dr. Rosenfeld’s patients tell him they’re nervous, he usually tells them: “The fact of the matter is that I get nervous when a patient doesn’t get nervous. Your nervousness tells me that you understand the risks and benefits of what we’re about to do. This isn’t like going to a drive-through McDonald’s where every hamburger is made the same way. Even though there’s a 98 percent success rate around the country, there’s still risk involved.” He assures the patient that he’ll do everything in his power to achieve optimal results. “We’re in this together,” he says.

Verbal Anesthesia

Two common fears patients have about cataract surgery are receiving insufficient anesthesia and seeing the surgeon or surgical instruments coming at the eye. Dr. Rosenfeld recommends emphasizing to your patients that the anesthesia will not wear off too soon, although immediate action can and will be taken in that unlikely event. Frequent verbal reassurance regarding what sensations visual or otherwise the patient may be experiencing throughout the surgery is also essential.

How much information to share about what’s happening at each step of the surgery depends on the individual patient. “Most patients give you very clear signals about how much they want to know,” according to Dr. Rosenfeld. “There are some who want to know every detail about what you’re doing, and there are some who just want to be snowed.”

It’s usually about fifty-fifty, according to Dr. Henderson. “Either way, I always warn patients before injecting intracameral lidocaine, before inserting the phaco or I&A probe, and before injecting the IOL,” she said. “This allows them to brace themselves for any pressure or pain and to avoid any abrupt movements.”

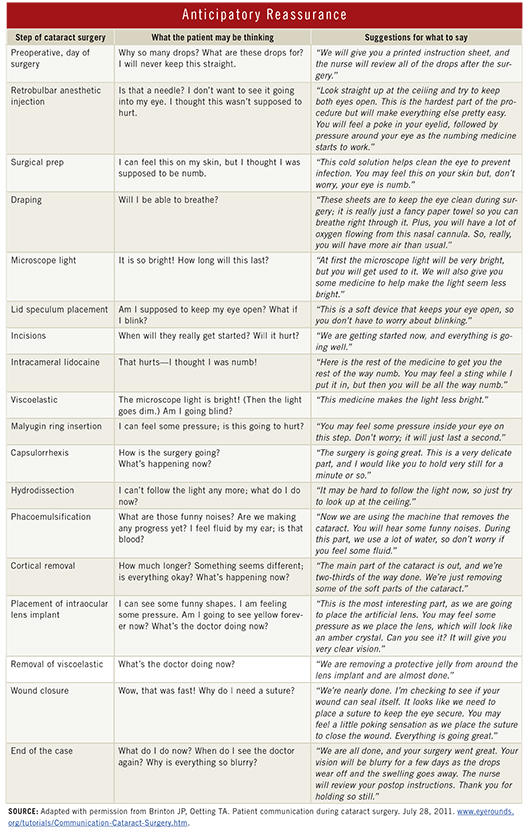

Anticipatory reassurance is also essential when there is a discussion about reloading an IOL, repriming the phaco machine, or any other change from the normal procedure. “While the surgical team understands that these types of slight irregularities are inconsequential and occur regularly, a patient lying on the table may become anxious if they believe there is a complication,” said Dr. Henderson.

Dr. Oetting finds that prefacing patient instructions during surgery with a phrase such as “For your safety, I’d like you to do x, y, or z,” sets a calm, professional tone. An appropriate amount of anticipatory reassurance balanced with silence provides great comfort to the patient, he said.

(click to expand)

Nonverbal Comfort

Some anesthesiologists, anesthetists, or nurses hold the patient’s hand to provide support during surgery. The power of this practice cannot be overstated, said Dr. Rosenfeld. In one study of cataract surgery patients under local anesthesia, hand-holding by a nurse significantly reduced patient epinephrine levels and self-reported intraoperative anxiety.3

Drs. Rosenfeld, Henderson, and Oetting all like to have music playing in the OR, as it decreases anxiety for the patient and surgical team alike. New research shows that listening to soothing music and nature soundscapes through headphones can significantly reduce anxiety during cataract surgery. Embedding “binaural beats” audio two different pitch frequencies, one transmitted into each ear through stereo headphones into the music also lowers anxiety, heart rate, and blood pressure, according to one study.4

___________________________

1 Mokashi A et al. Eye Lond. 2004;182:147-151.

2 American Academy of Ophthalmology Cataract and Anterior Segment Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines: Cataract in the Adult Eye. October 2011. Accessed April 25, 2013.

3 Moon JS, Cho KS. J Adv Nurs. 2001;353:407-415.

4 Vichitvejpaisal P. Soothing sounds during cataract surgery reduces patient anxiety. Poster presented at: Annual Meeting of American Academy of Ophthalmology; Nov. 12, 2012; Orlando, Fla. Accessed June 18, 2013.

___________________________

Bonnie A. Henderson, MD, is clinical professor of ophthalmology at Tufts University and is in practice with Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston. Financial disclosure: Is a consultant for Alcon and Bausch + Lomb and has royalty interest in the Virtual Mentor cataract training system.

Thomas A. Oetting, MD, is professor of clinical ophthalmology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and chief of the eye service at Iowa City Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Financial disclosure: None.

Steven I. Rosenfeld, MD, is voluntary professor of ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute and is in practice with Delray Eye Associates, Delray Beach, Fla. Financial disclosure: Is a lecturer for Allergan and a consultant for Modernizing Medicine.