By Margaret L. Pfeiffer, MD, Omar Ozgur, MD, Bradley Thuro, MD, and Bita Esmaeli, MD

Edited by Sharon Fekrat, MD, and Ingrid U. Scott, MD, MPH

Download PDF

Surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for periocular basal cell carcinoma (BCC), the most common eyelid malignancy. Adjuvant radiation may be used in selected cases. Neither radiation therapy as primary modality nor cryotherapy is considered to be as effective as surgery; these techniques have historically been reserved for patients who are not good surgical candidates.

Although distant metastasis of BCC is rare, local invasion and destruction may lead to significant orbital and ocular morbidity. In cases of large tumor size, multiple lesions, or locally recurrent disease, surgical excision or extensive radiation may result in substantial ocular morbidity, facial disfigurement, or loss of the eye.

Medical Alternatives: Vismodegib and Sonidegib

Targeted nonsurgical therapy—specifically, the use of Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway inhibitors—has provided a viable new treatment alternative for locally advanced periocular BCC and metastatic BCC, as well as for patients who have basal cell nevus syndrome with multiple symptomatic lesions.

The 2 targeted SHH pathway inhibitors approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for BCC are vismodegib (Erivedge) and sonidegib (Odomzo). Vismodegib has been used successfully and reported in several series of patients with locally advanced or metastatic periocular BCC or basal cell nevus syndrome with symptomatic periocular lesions. Both drugs are formulated as capsules, to be taken once daily.

|

|

LOCALLY ADVANCED BCC. (1A) At presentation to our hospital, this patient had BCC involving the upper and lower eyelid and a large area of facial skin, with extension onto the ocular surface. (1B) Same patient; treatment effect after 3 months of vismodegib therapy.

|

Mechanism of Action

The SHH pathway is a molecular signaling pathway involved in both fetal development and postnatal tissue regulation. In the fetus, this pathway is involved with the developmental process in the limbs, brain, spinal cord, and more. In the nonmutated hedgehog pathway, a transmembrane receptor and tumor suppressor known as Patched 1 (Ptc) inhibits the downstream receptor Smoothened (Smo).

Mutations of this pathway, which have been implicated in sporadic BCC and in basal cell nevus syndrome, remove the inhibition on Smo and lead to cellular proliferation, tumorigenesis, and angiogenesis.1 Therefore, targeting this mutated pathway with selective SHH pathway inhibitors halts cellular proliferation and tumor growth. Vismodegib and sonidegib both target this pathway through Smo. Vismodegib acts as a competitive antagonist at the Smo receptor,1 while sonidegib inhibits Smo expression.2

Indications and Dosing

The FDA approved vismodegib for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic BCC in January 2012.3 It has since been used successfully for locally advanced BCC in the periocular region and has also shown impressive results in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome.3-7 The approved dose of vismodegib is 150 mg daily by mouth.

In July 2015, sonidegib was approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic BCC at a dose of 200 mg daily by mouth. To our knowledge, there are no randomized trials comparing the efficacy of the 2 drugs.

Outcomes

Outcome data on the efficacy of vismodegib in patients with periocular lesions are limited to several case reports and small case series.4-6,8 We have found no publications that specifically discuss sonidegib for periocular BCC.

In a report on 7 patients with locally recurrent periocular BCC treated with vismodegib for a mean duration of 11 weeks, 6 patients (86%) achieved a response.6 Two patients (29%) had a complete response, and 4 patients had a partial response. One patient’s tumor progressed.

In 12 patients treated with vismodegib at our institution (10 with locally advanced BCC and 2 with basal cell nevus syndrome), 3 patients (25%) had a complete response, 6 (50%) had a partial response (Figs. 1 and 2), and 3 (25%) achieved disease stability.4 Two patients, one with an initially complete response and the other with an initially stable response, went on to develop progressive disease at 38 and 16 months, respectively, after starting treatment.

In another series of 8 patients (7 with locally advanced BCC and 1 with basal cell nevus syndrome), 4 patients (50%) achieved a complete response, and 4 (50%) achieved a partial response.9 In 1 patient with orbital involvement who achieved a complete response, vismodegib was used as adjuvant therapy for positive surgical margins.

Taken together, these results certainly show promise, demonstrating a significant clinical response, even if partial, in a majority of patients. This is particularly important considering that patients included in these reports had often undergone multiple previous surgeries for recurrent lesions and had such large locally advanced lesions that orbital exenteration or other major disfiguring surgery or significant ocular morbidity from surgery would otherwise have been expected.

|

|

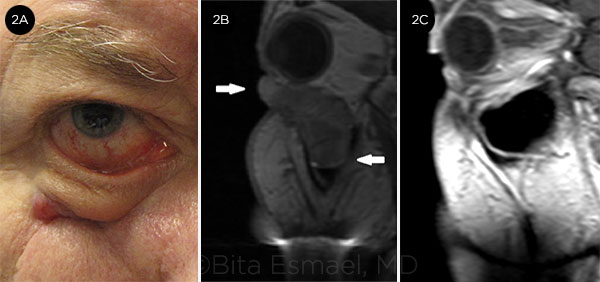

RECURRENT BCC. (2A) BCC in the right lower eyelid and premaxillary area. (2B) MRI shows large, bulky tumor extending into the maxillary sinus. Maxillectomy and probable exenteration were planned; instead, the patient was treated with vismodegib. (2C) After 2 years of treatment, the lesion had almost completely resolved. Biopsies of the lower eyelid and maxillary sinus mucosa revealed no residual cancer.

|

Safety and Adverse Events

Vismodegib. In the study of 104 patients that ultimately led to FDA approval of vismodegib for BCC, all patients experienced treatment-related adverse events (AEs); however, they were categorized as mild to moderate in half of the patients.3,10 These common AEs typically occurred within the first 6 months of treatment. The most frequently reported side effects that led to treatment discontinuation were muscle spasms, anorexia, and dysgeusia (altered sense of taste). Of 104 patients, 18 (17%) discontinued treatment due to AEs.

Serious AEs (including grade 3 or 4 muscle spasms, weight loss, and fatigue) occurred in 31.7% of patients at a median duration of drug exposure of 12.9 months. Seven deaths occurred during the treatment period, but their relationship with the drug is unknown.

Similarly, in 2 case series of patients with periocular BCC, the most frequently reported adverse events of vismodegib therapy were alopecia, dysgeusia, anorexia, and muscle spasms.6,9

Sonidegib. The most common adverse events noted in the recently published study of 230 patients that led to FDA approval of sonidegib were similar to those of vismodegib, notably muscle spasms, dysgeusia, and alopecia.2 Almost all patients experienced at least 1 adverse event. The most common grade 3 adverse event was elevated serum creatine kinase, which occurred in almost 30% of patients, although only a small percentage of these went on to develop rhabdomyolysis.

Teratogenic effects. Both vismodegib and sonidegib carry black box warnings owing to their potential to cause fetal death or severe birth defects. Appropriate precautions should be taken by women of childbearing age.

Cost

The cost of vismodegib in the United States is approximately $7,500 per month, or $250 per capsule.11 We are unable to find information on the anticipated cost of sonidegib.

Future Applications

Currently, vismodegib and sonidegib are FDA approved only for metastatic or locally advanced BCC. Off-label uses such as in the neoadjuvant setting—that is, to cause tumor shrinkage before definitive surgical excision—may be considered as a future application.

One patient in a series of 6 reported by Demirci et al. was treated with vismodegib as neoadjuvant therapy, although that protocol had not been the authors’ initial intention.9 This patient had recurrent morpheaform BCC with invasion into the medial orbit; he was initially treated with vismodegib for 5 months, and the size of the tumor decreased.8 However, because of intolerable muscle spasms, he chose to discontinue vismodegib therapy and to proceed with surgical resection of the residual tumor. Globe-sparing excision was successful, and histopathologic analysis of the resected tumor revealed an absence of Ki-67 protein (a marker of cellular proliferation), which was interpreted by the authors as indicating a histologic response of the tumor to therapy.

As with all off-label uses of medications, the physician must have a careful discussion with the patient of the risks and benefits of the treatment, and informed consent must be obtained.

Conclusion

In cases of metastatic or locally advanced periocular BCC, clinicians should consider the SHH pathway inhibitors vismodegib or sonidegib as an alternative to traditional surgical or radiation therapy only for patients in whom surgery or radiation would mean significant ocular morbidity or possibly loss of the eye. Use of these drugs, possibly followed by surgery for residual disease, may allow some patients to avoid orbital exenteration. SHH inhibitors are taken orally and have a favorable side effect profile with mostly mild (grade I or II) toxicity.

___________________________

1 Athar M et al. Cancer Res. 2014;74(18):4967-4975.

2 Migden MR et al. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):716-728.

3 Sekulic A et al. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(23):2171-2179.

4 Ozgur OK et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(2):220-227e2.

5 Yin VT et al. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;29(2):87-92.

6 Gill HS et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(12):1591-1594.

7 Tang JY et al. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(23):2180-2188.

8 Kahana A et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(10):1364-1366.

9 Demirci H et al. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(6):463-466.

10 Sekulic A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(6):1021-1026e8.

11 Fellner C. P T. 2012;37(12):670-682.

___________________________

Dr. Esmaeli is professor of ophthalmology and director of the Orbital Oncology and Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery Fellowship Programs; Dr. Ozgur is a fellow in Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery; and Dr. Thuro is a fellow in Orbital Oncology; all 3 are at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Pfeiffer is a resident at the Cizik Eye Clinic, University of Texas, Houston. Relevant financial disclosures: Drs. Ozgur, Pfeiffer, and Thuro: None. Dr. Esmaeli served on the Data Safety Monitoring Board for the European trial (STEVIE) of vismodegib for locally advanced BCC.