Download PDF

Good physician communication has the potential to be incredibly therapeutic. Beyond improving diagnostic accuracy, patient satisfaction, and adherence to treatment, it’s been shown to influence many types of patient outcomes, including pain control, day-to-day functioning, and physiologic measures such as blood pressure.1,2

“There’s ample scientific evidence showing the benefits of good physician communication,” said Richard A. Harper, MD, at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. “These benefits also extend to the physician, in the form of decreased burnout and malpractice rates, for example.”

Widely recognized as beneficial but unevenly practiced, the ideals of patient-centered communication challenge physicians to embrace a more holistic approach to medicine.

“Treating patients isn’t just about dispensing glasses and contacts, and it’s not just about being a great surgeon,” said Laura K. Green, MD, at LifeBridge Health Krieger Eye Institute in Baltimore. “Treating the whole person includes constantly communicating and building trust with that person.”

And given the documented tendency of physicians to overestimate their abilities in this arena,3 they should regularly review the simple, yet challenging, principles and practices of patient-centered communications.

Principles of Good Communication

Empathy, knowledge, clarity, and credibility are principles at the heart of excellent physician-patient communication, said Laura L. Wayman, MD, at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Empathy. The ability to identify with patients and their problems is a starting point, said Dr. Harper, which you can reinforce with verbal acknowledgment such as, “I understand and can appreciate what you are saying.” Also, he said, give encouragement when possible: “It looks like you’re doing a great job with your drops.”

Knowledge. Physicians learn to deal with complex pathophysiologic disease processes, said Dr. Harper, and are expected to communicate copious amounts of information and therapeutic recommendations. “Although knowledge of the subject matter is essential,” he said, “the only things patients can really judge us on is how they feel about the doctor-patient encounter. They’ll never really know how much we know or how well we operate.”

Clarity and credibility. Clear and credible communication requires excellent knowledge and the ability to speak concisely and in a way that the patient can understand, said Dr. Wayman. “It’s fairly easy to assess a patient’s level of sophistication by asking them up front what brought them in.”

Dr. Green agreed. “I aim to cultivate a way of explaining disease processes and treatments that is clear and free enough of jargon to be used to explain complex information to people with a limited education,” she said.

Challenges to Good Communication

Lack of understanding. One of the biggest barriers to good communication is simply not knowing patients well enough, said Dr. Wayman. For example, if you don’t understand patients’ level of comprehension about the concepts you’re discussing, this can lead to problems, such as talking over patients’ heads.

“Understanding can be further complicated by age or language barriers in immigrant populations or comorbidities such as dementia,” said Dr. Green. Lack of social support may also limit understanding if a patient relies heavily on family members who are not present during the visit, said Dr. Wayman.

Time constraints. “This can be a challenging barrier,” said Dr. Harper, “given that we’re working in a medical model that is volume- and procedure-based, not truly outcomes-based, in the sense that we’re not asking patients to formally evaluate us.”

Dr. Green suggested that this barrier is often one of perception rather than reality. “If you think ahead about different diseases you might see, it is possible to come up with a 30-second explanation using very neutral layman’s terms,” she said. “Then it doesn’t take any significant extra time.”

Regardless, said Dr. Harper, physicians can’t afford not to take the time to communicate well. “If you don’t address patients’ concerns, they may not come back or may fail to take their medications, develop complications, or have a poor surgical outcome,” he said. “Without good rapport, the relationship can become adversarial, translating into an angry patient.”

Angry patient. If you find yourself in this unpalatable position, said Dr. Green, it’s especially important not to reflect anger back at the patient. This can further exacerbate the antagonism. To calmly defuse the situation, you might say, “I see you’re upset. Help me better understand why. I want to hear your side of the story.” And, given the time constraints of an office visit, she said, it’s fair to say at the outset: “I want to give this issue its due, so if we need more time than allotted, let’s make another appointment to continue this discussion.”

Bad news. Time is also a consideration when delivering bad news, said Andreas K. Lauer, MD, at the Casey Eye Institute in Portland, Ore. “Patients and physicians alike need time to process difficult news,” he said. “To prevent delays to other patients waiting in clinic, there can be a tendency to trivialize bad news or not discuss it at all. This can be harmful and only heightens the patient’s anxiety. Giving patients some information is always better than giving none. You can let the patient know that you can use a later teleconference or future visit to continue the conversation. This also often facilitates better questions at the next office visit.”

Tips for Better Communication

“Some people think emotions cloud judgment,” said Dr. Harper. “I would argue that emotions inevitably play a part in every waking moment. Therefore, if I were to distill physician communication down to just one thing, it would be attending to the emotional needs of the patient.”

The following tips take those emotional needs into account.

Be an active listener. If you’ve encountered a conflict or difficult diagnosis with a previous patient during the day, take a deep breath and exhale, actively trying not to carry that into the next room, said Dr. Lauer. First impressions are critically important, added Dr. Harper. “Do you make eye contact? Sit on the same level with the patient? Communicate that you’re giving your full attention?”

Try to set up your keyboard so you can face the patient as you’re entering information into the electronic health record, said Dr. Wayman. If you must turn away for a moment, added Dr. Lauer, you can say, “Keep talking, I’m listening.” People are exquisitely sensitive to small, nuanced cues physicians give off, partly because of the position we’re in, added Dr. Harper. So, if you’re time crunched or frustrated, for example, your body language and demeanor may telegraph that, even if you’re saying all the right things.

By the same token, the patient tells you a lot with facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice, said Dr. Lauer. “Maybe 25 to 30 percent of the content is what they tell me verbally and the rest is communicated by whether they sound or look anxious, angry, or sad.”

Part of active listening involves reflecting back what the patient has told you to ensure that you understand and to communicate that you’re listening, said Dr. Green. Likewise, you can ask the patient to repeat what they understand about the treatment plan.

Adapt. As you get better at recognizing and adapting to different communication styles, said Dr. Harper, you’ll improve at directing the conversation and become faster in addressing the key issues. “This is not a cookie-cutter approach,” he said. “Some patients will talk until you interrupt them. Others will require more specific questions to draw them out.”

Ask open-ended questions. You’ll learn more about the patient if you avoid asking leading questions, said Dr. Green. For example, if you’re trying to verify the medications a patient is taking, don’t ask, “Now, you’re taking all your glaucoma drops as you’re supposed to, right?” And don’t say, “I see here in the chart that you take timolol twice a day and latanoprost at bedtime, right?”

Instead, she advises using a neutral, calm tone of voice to say something like this: “It can be hard to keep all these drops straight. Tell me how you use the drops.” This not only helps you discern what’s going on, said Dr. Green, but also helps you build trust with the patient.

Use aids. In addition to using simpler terms to explain complex concepts, the ophthalmologist can capitalize on aids such as large-print patient education devices and materials, said Dr. Wayman. “A plastic model of the eye is particularly useful when explaining the natural lens of the eye, for example, and the steps of cataract surgery.” It can also help to have family members present to listen and ask questions.

Maximize use of the team. “When people come to your office, they don’t just see you,” said Dr. Wayman. The patient’s experience begins with whoever answers the phone, said Dr. Lauer, and includes front office staff, medical assistants, technicians, and, in academic centers, trainees. “Health care extenders such as technicians may spend a lot of time—often more than you—communicating with patients,” said Dr. Harper. “Through them, you can improve the patient experience without spending extra time yourself.”

End With a Question

At the end of patient visits, many physicians feel the weight of the waiting room bearing down on them. But this is the time to slow down and ask one more question, advises Dr. Green.

Don’t say, “You don’t have any other questions, do you?” or “Do you have any other questions?” These both indirectly communicate, “I hope you don’t have any other questions.” Instead, stop, look the patient in the eye, and ask, “Now, what other questions do you have?” That’s an invitation to questions, she said, and it ends the exam on a positive note because you come across as very caring.

Many physicians are reluctant to answer patients’ questions because patients seem to have so many, said Dr. Green. “But I actually find that the vast majority of the time, people don’t have any more questions by the end of the visit. If they do, it’s often the most important one, and answering it helps prevent a phone call. It also doesn’t keep me from seeing all my patients in a timely fashion.”

Assess and Improve Your Skills

Before you take steps to improve, you need insight about the level of your communication skills.

Assess. Direct, immediate feedback from patients and peers is invaluable. You might ask a staff member to sit in and provide you with an evaluation, said Dr. Green. You can also glean information from patient satisfaction surveys, staff reports, and online reviews, and by assessing the numbers of referrals you are getting.

“Do your patients leave the room understanding their disease and the treatment process?” asked Dr. Wayman. “If you aren’t certain they understand why they need to take the drops, have the injections, or do the surgery, then you probably have work to do.”

Observe. You can gain an understanding of how to improve your communication skills by observing peers or mentors who are physicians, said Dr. Wayman.

Push yourself. To improve your skills, take a leadership position, advised Dr. Wayman. “For example, present at local meetings, participate in workshops, or volunteer to work on a project or committee or to teach a course through the Academy.”

Write. This can help you organize, filter, and refine your thoughts before you communicate them verbally, said Dr. Wayman. “For example, writing a clear and succinct clinical note about the history or exam will help you present that information out loud.”

Find a coach. This doesn’t need to be a paid coach, said Dr. Wayman. It could be a colleague or senior partner you trust who can observe you and provide feedback later. Have them take notes and watch you interact with a few patients in the clinic for a couple of hours. “This person might even help you develop a plan for improvement,” she said.

Take a course. Communication skills can lapse over time. For a regular review, take advantage of resources like these: Institute for Healthcare Communication or Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care.

Some studies show that communication training programs—often taken for CME credit—don’t have to take a lot of time to make a real difference, said Dr. Harper. Even online courses such as Astute Doctor Education, added Dr. Green, can do a great job through the use of patient anecdotes, common real-world scenarios, and evidence-based techniques.

Astute Doctor

The Astute Doctor learning modules that are available to all Academy members at https://www.aao.org/residents cover the following topics:

- Building Strong Patient Relationships

- Eliciting Patient Concerns

- Maximizing Patient Understanding & Recall

- Motivating Patient

- Patient-Centered Information Gathering

- Setting Mutually Agreed Goals.

|

___________________________

1 Travaline JM et al. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2005;105(1):13-18.

2 Stewart MA et al. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;15(9):1423-1433.

3 Fong Ha J et al. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38-43.

___________________________

Dr. Green is an ophthalmologist at LifeBridge Health Krieger Eye Institute in Baltimore. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Harper is professor of ophthalmology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Lauer is professor of ophthalmology at Casey Eye Institute at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Wayman is associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

___________________________

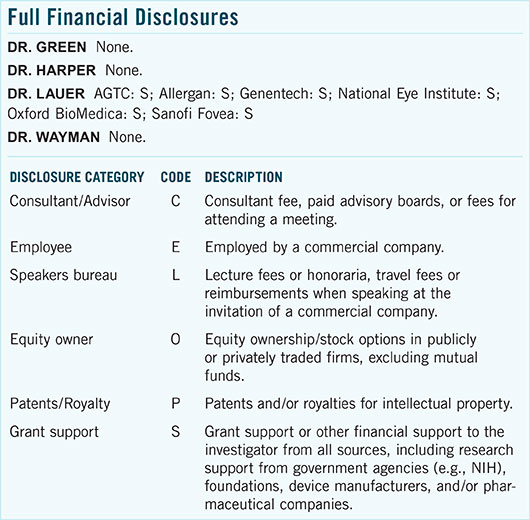

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.