By R. Keith Shuler Jr., MD, and Prithvi Mruthyunjaya, MD

Edited Ingrid U. Scott, MD, MPH, and Sharon Fekrat, MD

This article is from February 2006 and may contain outdated material.

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) is often a straightforward clinical diagnosis when it presents as a typical serous neurosensory retinal detachment in a middle-aged male. However, atypical presentations or chronic cases are more of a challenge. CSCR is a diagnosis of exclusion. Care must also be taken to ensure that corticosteroid administration is not exacerbating the CSCR.

Etiology

Despite observations using indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) that suggest that CSCR is primarily a choroidopathy,¹ debate continues over whether the primary underlying pathology is at the level of the choroid, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) or both.

Presentation

Demographically, CSCR is believed to be predominantly a disease of men 20 to 45 years of age; however, in women and older patients (> 50 years) CSCR may be more common than initially reported. CSCR diagnosed after age 50 should raise a high suspicion of neovascular age-related macular degeneration instead.

CSCR is more common in Cauca-sians, Hispanics and Asians, and less common in those of African descent. Persons with CSCR have a reported higher prevalence of migrainelike headaches or psychiatric conditions, including hypochondria, hysteria and conversion disorder. High-stress occupations or lifestyles also have been associated with CSCR.

Patients with CSCR may complain of decreased visual acuity, micropsia, metamorphopsia, abnormal color vision and scotomas. Patients may be asymptomatic if the fovea is uninvolved.

Corticosteroids have long been described as an exacerbating or precipitating factor in CSCR.² The ophthalmologist should carefully question a patient with CSCR to determine any recent corticosteroid use. Affected individuals may have forgotten previous intraarticular corticosteroid injections or may not realize that their inhaler, nose spray or skin cream contains corticosteroids. The ophthalmologist may need to communicate with the other physicians coman-aging the patient’s care to ensure that only corticosteroid-sparing medications are being used. This is particularly crucial in chronic or recurrent cases because the lack of resolution may be due to unrecognized corticosteroid use.

A patient with CSCR usually presents with visual acuity in the range of 20/20 to 20/200, with an average presenting visual acuity of 20/30. Visual acuity can often be improved with a small hyperopic correction given the associated shallow neurosensory detachment.

Amsler grid testing may demonstrate metamorphopsia in eyes with near-normal visual acuity. The anterior segment and vitreous are normal with no evidence of inflammation.

A dilated fundus examination with biomicroscopy and indirect ophthalmoscopy is essential to appreciate the characteristic findings of CSCR. These typically include a round, well-delineated, shallow, serous macular neurosensory detachment, which is often surrounded by a halo light reflex. If the fovea is involved, the normal foveal light reflex is absent and a prominent yellow-colored dot—presumably due to retinal xanthophyll—may be visualized in the foveal region. Subretinal fibrin precipitates may be seen as multiple, gray-white, dotlike condensations on the posterior surface of the detached retina. Small, round, yellow or gray serous RPE detachments (PEDs) may be discernable. These serous PEDs are typically less than a quarter of a disc diameter in size, are located in the superior half of the neurosensory detachment and may be surrounded by a pink halo. RPE atrophy may be pres-ent in one or both eyes as evidence of an active or previous CSCR episode. Occasionally, the neurosensory detachment is isolated below a serous PED due to a gravitational force acting on the subretinal fluid.

Inferior, peripheral, atrophic RPE tracts (linear pigment lines) characterize a less common type of CSCR associated with a poorer prognosis. Excessive or prolonged subretinal leakage is responsible for this type of CSCR. Gravity causes the subretinal fluid to collect inferiorly, forming a “teardrop” or “hourglass” shape. If the patient is placed in a recumbent position, the subretinal fluid shifts. Additional manifestations of chronic retinal detachment in these eyes may include cystoid macular edema, extrafoveal cystoid changes in the detached retina, lipid deposits, retinal telangiectasia, CNV and perivascular or bone spicule pigmentation patterns. This more severe type of CSCR is more common in persons of Hispanic or Asian ancestry.

Another atypical variant of CSCR usually is found in healthy middle-aged men and presents with multiple PEDs and multiple bullous serous neurosensory detachments that demonstrate shifting fluid. These detachments are located in the midperiphery or more posteriorly. This form of CSCR is characterized by a more fibrinous subretinal exudate that imparts an opaque appearance to the subretinal fluid. Late sequelae of this fibrinous exudate include subretinal fibrosis, CNV or RPE rips.

Ancillary Testing

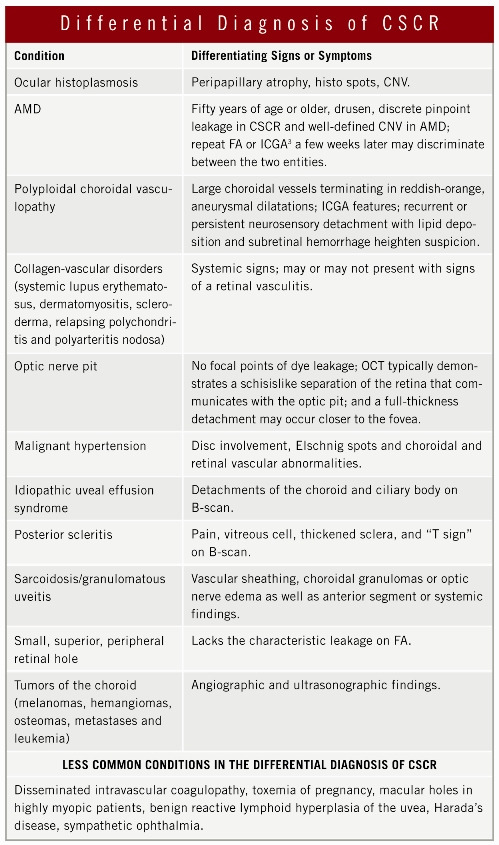

Fluorescein angiography is often used to establish the diagnosis of CSCR and rule out other conditions (see the table “Differential Diagnosis”). Frequently, FA demonstrates single or multiple discrete leakage points that evenly distribute dye throughout the subretinal fluid or that may reveal evidence of a PED. The classic “smokestack” appearance occurs in less than 20 percent of cases.

Ocular coherence tomography demonstrates the neurosensory detachment in addition to any PED associated with the CSCR. Also, OCT is an objective way to follow changes in the amount of subretinal fluid. In some cases, ICGA may be required to differentiate between CSCR and AMD or polyploidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV). Multiple areas of choroidal hyperpermeability in the mid-to-late phases of ICGA are indicative of CSCR and not AMD or PCV.³

Natural History

Generally, CSCR has a good prognosis for spontaneous visual recovery, with the vast majority of eyes stabilizing with 20/30 to 20/40 visual acuity. The neurosensory detachments usually resolve within three to four months, but vision may continue to improve up to a year later. One-third to one-half of CSCR cases will recur, and 10 percent of recurrences will have at least three episodes. Of the eyes that have more than one episode, nearly 50 percent recur within one year of the initial incident. Even after anatomical resolution, visual symptoms may include abnormal color vision, metamorphopsia, micropsia and relative scotomas.

Certain features and coexistent conditions are associated with lower final visual acuity. Patients who develop persistent or recurrent foveal detachments, CNV, subretinal fibrosis, subfoveal RPE atrophy, multiple sites of leakage, larger PEDs, cystoid macular edema, dependent detachments and atrophic RPE tracts have a poorer prognosis. Also associated with a poorer prognosis are concomitant end-stage renal failure, organ transplantation, pregnancy, corticosteroid use or elevated endogenous cortisol levels.

Treatment

No medical treatment has proven effective for CSCR; however, acetazolamide has been suggested to hasten the resolution of subretinal fluid. Corticosteroids are contraindicated and have no therapeutic role in CSCR.²

Direct focal laser photocoagulation, with low-intensity laser burns to the leakage site, abbreviates the disease course but has no effect on final visual acuity or recurrence rate. Because of the generally good prognosis of CSCR and the tangible risks associated with laser photocoagulation to the macula, including scarring and secondary CNV formation, laser treatment is seldom indicated for CSCR.

______________________________

1 Guyer, D. R. et al. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:1057–1062.

2 Haimovici, R. et al. Ophthalmology 2004;111(2):244–249.

3 Spaide, R. F. et al. Retina 1996;16(3):203–213.

______________________________

Dr. Shuler is a vitreoretinal fellow and Dr. Mruthyunjaya is assistant professor of ophthalmology on the vitreoretinal service as well as the director of the ocular oncology service; both are at Duke University. This work is supported in part by the Heed Ophthalmic Foundation.