EPIDEMIOLOGY

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cataract is the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment in the world (47.9%).

- The overall prevalence of visual loss as a result of cataract increases each year as the world’s population ages.

- In 2002, cataract caused reversible blindness in more than 17 million (47.8%) of the 37 million blind individuals worldwide; this figure is projected to reach 40 million by year 2020.

- Cataract accounts for 30%–50% of blindness in most African and Asia countries.

- Cataracts occur earlier in life in developing countries and in rural areas, and the incidence is higher.

|

Table 1. Population Surveys of Blindness Due to Cataract

|

|

Country

|

Prevalence of Blindness by WHO definition1 (%)

|

Blindness Due to Cataract and Complications (%)

|

|

Nepal

|

0.84

|

72.1

|

|

Chad

|

2.31

|

48.0

|

|

The Gambia

|

0.7

|

55.0

|

|

India

|

0.7

|

80.1

|

|

SE Turkey

|

0.4

|

50

|

|

Morocco

|

0.76

|

54.6

|

|

1WHO blindness definition: less than 3/60 in the better eye, with best correction

|

|

Table 2. Estimates of Worldwide Distribution of Cataract Surgery

|

|

WHO Region

|

Population (millions)

|

Number of Cataract Operations per Year (millions)

|

Cataract Surgical rate (operations/million/year)

|

|

Africa

|

650

|

0.2

|

300

|

|

Eastern Mediterranean

|

500

|

0.5

|

1000

|

|

Western Pacific

|

1650

|

1.65

|

1000

|

|

Western Europe

|

400

|

1.6

|

4000

|

|

Eastern and Central Europe

|

500

|

0.5

|

1000

|

|

South East Asia

|

1500

|

3..6

|

2400

|

|

North America

|

300

|

1.65

|

5500

|

|

Central and South America

|

500

|

0.5

|

1000

|

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

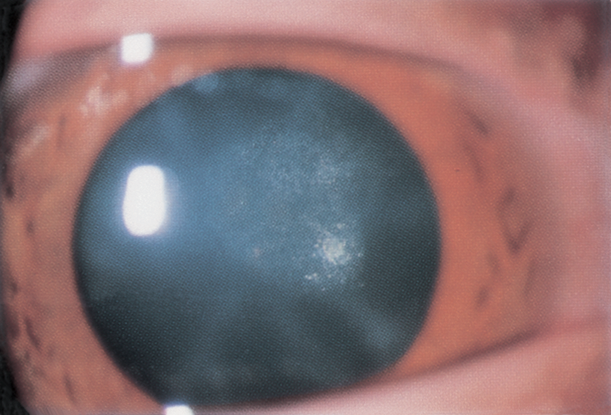

- Posterior subcapsular cataract (Figure 1)

- Cortical cataract (Figure 2)

- Congenital cataract (Figure 3)

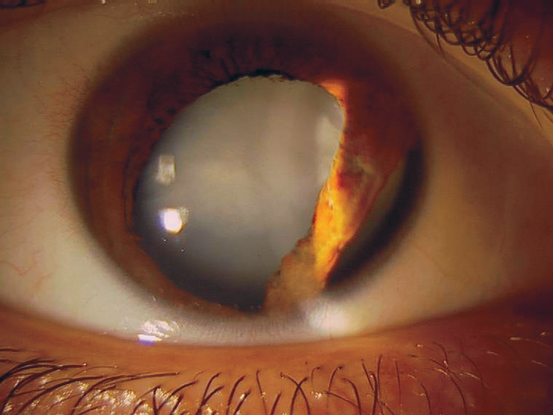

- Traumatic cataract figure (Figure 4)

- Drug-induced cataract

- Uncorrected refractive error

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DEFINITION

- Nuclear sclerotic cataract is sclerosis and yellowing of the lens.

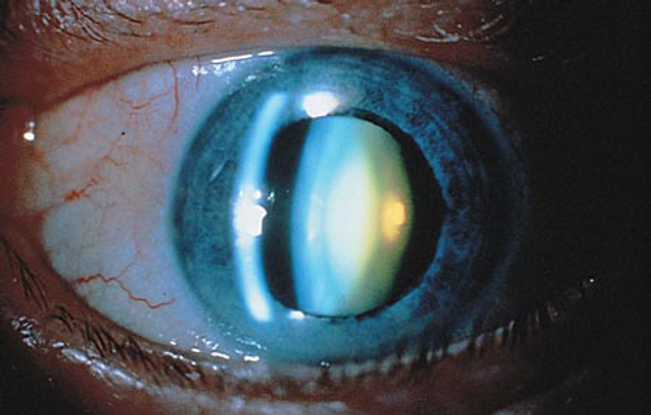

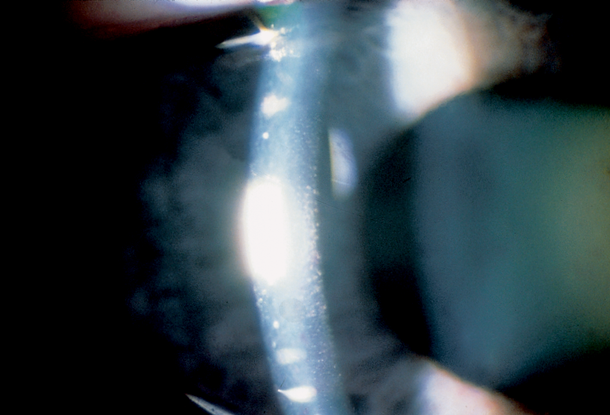

- This is evaluated on exam with a slit-lamp biomicroscope (Figure 5).

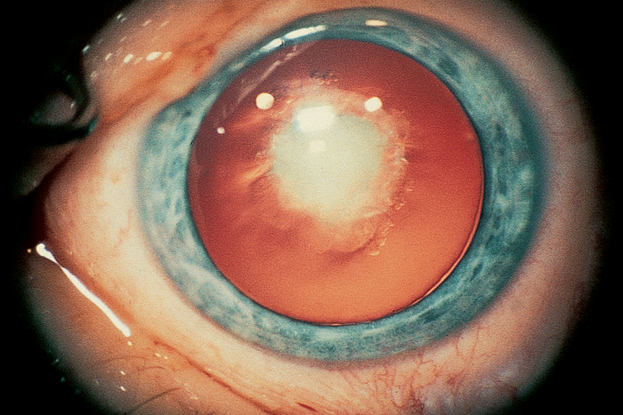

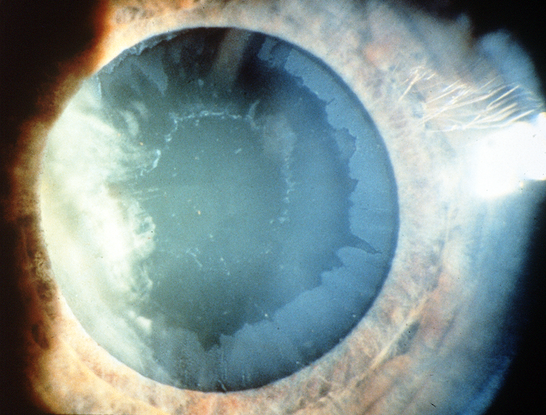

- Nuclear cataracts progress slowly over years to decades. A cataract is called mature when the lens is totally opacified (Figure 6).

- They are usually bilateral and often asymmetric.

- Nuclear cataracts typically cause greater impairment of distance vision than of near vision.

- In advanced cases, the lens nucleus becomes opaque and brown and is called a brunescent nuclear cataract.

Histopathology

- Lens fibers are continually produced throughout life in the adult lens eventually causing mechanical compression

- This compression causes hardening of the lens nucleus.

Nuclear cataracts are associated with changes in the lens structural proteins (a-, b- and g-crystallins). This causes formation of high-molecular-weight proteins. Altered lens proteins cause yellowing.

- On electron microscopy, the cells are very electron dense, exceedingly folded, and tightly packed, with obliteration of the intercellular spaces.

Wilmer Nuclear Opacity Grading

The Wilmer system uses 4 nuclear standard photographs for grading nuclear opacities (Figure 7). The grades are defined as follows:

- Nuclear Grade 0: No opacity. Less dense or less extensive than standard photograph 1.

- Nuclear Grade 1: Nuclear opacity present but consistent with 20/20 vision. At least as dense and as extensive as standard photograph 1, but less dense and less extensive than standard photograph 2.

- Nuclear Grade 2: Nuclear opacity consistent with vision in the range 20/25 to 20/30. At least as dense and as extensive as standard photograph 2 but less dense and less extensive than standard photograph 3.

- Nuclear Grade 3: Nuclear opacity consistent with vision 20/40 to 20/100. At least as dense and as extensive as standard photograph 3 but less dense or less extensive than standard photograph 4.

- Nuclear Grade 4: Nuclear opacity consistent with visual acuity of less than 20/100. At least as dense and extensive as standard photograph 4.

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the greatest risk factor for cataract. Other risk factors for nuclear sclerotic cataract include the following:

- Old age

- Female

- Nonwhite race

- Genetics

- Low socioeconomic status

- Cigarette smoking

- Low educational status

- High body max index (BMI)

- High sun exposure at younger age

- Ionizing radiation

- Diabetes mellitus

SIGNS/SYMPTOMS

- Moderate lenticular induced myopia

- The development of cataract may increase the dioptric power of the lens.

- Glare

- Dyschromatopsia

- Progressive decreased visual acuity

- Monocular diplopia

- Focal or diffuse lens opacification

- Grey, yellow, green or brown

MANAGEMENT

Nonsurgical Management

- Refraction for spectacle correction to improve distance and near vision

- Increased ambient light

- Pupillary dilation with mydriatic eye drops to possibly improve visual function in patients with small axial cataracts

- Low vision aids such as magnifiers

Surgical Management

Indications:

- Visual improvement as desired by the patient

- The presence of phacolytic or phacomorphic glaucoma, phacoantigenic uveitis, and dislocation of the lens into the anterior chamber.

Risk Factors for Surgical Complications

- Current or past use of sympathetic alpha-1A antagonist medications such as prazocin and tamsulosin are associated with intraoperative floppy iris syndrome

- Previous vitrectomy or vitreous hemorrhage

- A pupil with poor dilation may cause inadequate exposure during surgery

- Corneal abnormalities can cause a poor view during surgery or poor wound closure following surgery (Figure 8)

- Cataract surgery in patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome are a risk for a poorly dilating pupil, zonular dialysis and capsular tear (Figure 9)

Methods of Surgical Intervention

Extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE):

- Indicated for dense and mature cataracts (Figure 5).

- The lens nucleus and cortex are removed through an opening in the anterior capsule, leaving the capsular bag in place.

Phacoemulsification:

- An extracapsular technique performed with an ultrasound instruments that fragments the nucleus of the cataract and aspirates the material.

- There are different techniques of emulsification:

- Divide and conquer technique

- Phaco and chop technique

- Stop and chop technique

- Choo choo chop and flip technique

- Chip and flip technique

- Crack and flip technique

IMAGE LIBRARY

Differential Diagnosis

Figure 1. Early cataract formation. Note posterior subcapsular location of opacity. (Reproduced, with permission from Raab EL, Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 6, Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

Figure 2. Cortical cataract. A. Focal cortical cataract from a small perforating injury to the lens capsule. B. Focal cortical cataract viewed by retroillumination. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 3. Congenital cataract. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 4. Traumatic cataract and iridodialysis secondary to a paintball injury. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of Mark H. Blecher, MD.)

Pathophysiology/Definition

Figure 5. Nuclear cataract. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 6. Mature cataract. A cataract is called mature when the lens is totally opacified. A red reflex cannot be obtained; the pupil appears white and the fundus completely obscured. The radial spokes in this figure reflect variations in density of the radially arranged fibers in the cortical layers of the lens. Light still reaching the retina is totally diffused and will allow the perception of light but not form. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 7. The Wilmer grading system of nuclear opacities(© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of Sheila West, PhD.)

Figure 8. Specular reflection can make visible deep corneal guttae (orange-peel-like, dark indentations of the endothelium caused by focal excrescences of Descemet’s membrane) in early Fuchs corneal dystrophy (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 9. Pseudoexfoliation. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

REFERENCES

Al-Akily SA, Bamashmus MA. Causes of blindness among adult Yemenis: a hospital-based study. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2008;15:3–6.

Foster A. Vision 2020: the cataract challenge. Community Eye Health. 2000;13:17–19.

Friedman NJ, Kaiser PK. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2009.

Javitt JC, Wang F, West SK. Blindness due to cataract: epidemiology and prevention. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:159–177.

Kanski JJ, Bowling B. Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. 7th ed. Edinburgh; New York : Elsevier/Saunders, 2011.

Khanna R, Pujari S, Sangwan V. Cataract surgery in developing countries. Current Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:10–14.

Lens and Cataract. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 11, 2009–2010. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2009.

Malhotra R. Eye Essentials: Cataract Assessment, Classification and Management. Edinburgh; New York: Butterworth Heinemann/Elsevier, 2008.

Ministry of Health, Jordan. WHO. “Summary of the National Prevalence Study for Blindness and Low Vision.” Jordan: 2008.

Oduntan AO, Prevalence and causes of low vision and blindness worldwide. S Afr Optom. 2005; 64:44–54. Accessed October 2, 2013.

Taylor HR. Cataract: how much surgery do we have to do? Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1–2.

West SK, Rosenthal F, Newland HS, Taylor HR. Use of photographic techniques to grade nuclear cataracts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:73–77.

Yanoff M, Duker JS. Ophthalmology. 3rd. Edinburgh: Mosby/Elsevier, 2009.

World Health Organization. “Causes of Blindness and Visual Impairment.” Geneva: Health Organization. Accessed October 2, 2013.

Yanoff M, Sassani JW. Ocular Pathology.6th ed. Edinburgh: Mosby/Elsevier, 2009.

CONTRIBUTORS

Executive Editor: R. V. Paul Chan, MD, FACS, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Section Editors:

North Africa/Middle East:

Ebtisam S. Kadhem Al-Alawi, FRCS, MRCOpht, DO, Salmaniya Medical Center, Bahrain

Assistant Editors:

Swetangi D. Bhaleeya, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Kristin Chapman, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Peter Coombs, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Michael Klufas, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Samir Patel, medical student, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Region Contributor:

Ahmed Nageeb Shokry Zewar, MD, Ophthalmology Department, Jordan University Hospital, Amman, Jordan

Ghada AlBayat, MD, Senior Resident, Salmaniya Medical Complex, Bahrain

Copyright © 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology®. All Rights Reserved.