EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- Worldwide, fungal keratitis is a significant cause of ocular morbidity and unilateral blindness.

- The incidence varies with climate and fungal keratitis is more common in tropical regions.

- In the US, fungal keratitis remains rare, but fungi are a more common cause of corneal ulcers in Southern states (35% in South Florida) than in Northern ones (8.3% in New York).

- Contact lens wear increases the risk of fungal keratitis.

- Topical steroid use is also associated with increased risk of fungal keratitis, especially Candida keratitis.

- In 2006, an outbreak of 130 cases of Fusarium keratitis in the United States was linked to Bausch & Lomb ReNu contact solution.

- Fungal keratitis is a common cause of corneal ulcers in developing nations, accounting for 44% of corneal ulcers in South India, 36% in Bangladesh, 37.6% in Ghana, and 17% in Nepal.

- Fungal keratitis often occurs following ocular trauma from vegetable matter; thus, agricultural workers are at greater risk.

- Fungal keratitis is more common in males than in females.

Regional Information (India)

- Prevalence varies by region and is highest in South India (36.7% of corneal ulcers) but is also common in West India (36.3%) and East India (26.4%). Fungal keratitis is a much less common cause of corneal ulcers in Northern India (7.3%).

- Males are affected more commonly than females (65-71% of patients are male).

Fungal keratitis occurs more frequently during the wet monsoon season (June-Sept).

- History of recent ocular trauma is common (reported by 54.4% of patients in one study).

- Fusarium and Aspergillus species are the most common isolates (37.2% and 30.7%, respectively).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DEFINITION

Fungal keratitis may be caused by filamentous or nonfilamentous fungi.

Fungal keratitis caused by filamentous fungi (Fusarium or Aspergillus species) typically occurs secondary to ocular trauma from vegetable matter in previously healthy eyes. Fungi are ubiquitous in the environment and gain access to the cornea through epithelial defects. The epithelial defect is often caused by the trauma that introduces the fungus but may be secondary to contact lens wear or to prior ocular surgery. In developing countries, ocular trauma among agricultural workers is the most common setting of fungal keratitis.

Once in the cornea, fungi can penetrate through an intact Descemet membrane and into the anterior chamber via proteolytic enzymes. As such, fungal keratitis is devastating, difficult to treat, and remains a common cause of unilateral blindness in tropical countries.

Nonfilamentous yeasts (Candida species) typically cause keratitis in eyes with preexisting ocular surface disease or eyes that have recently been treated with topical steroids.

SYMPTOMS/SIGNS

Symptoms

- Pain

- Blurry vision

- Photophobia

- Red eye

- Tearing

- Discharge

- Foreign body sensation

- Corneal ulceration

- History of contact with vegetable matter

Signs

| Filamentous fungi (i.e. Fusarium, Aspergillus, Curvularia) |

Nonfilamentous fungi (i.e. Candida)

|

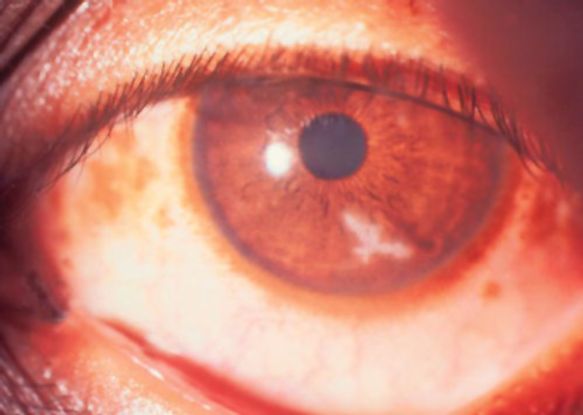

- Gray-white corneal stromal opacity with feathery white border (Figures 7-11)

- Satellite lesions surrounding 1° infiltrate

- Epithelial defect or corneal ulcer

- Anterior chamber reaction

- Hypopyon

- Inflammatory ring

|

- Yellow-white stromal infiltrate

- Epithelial defect or corneal ulcer

- + /- Anterior chamber reaction

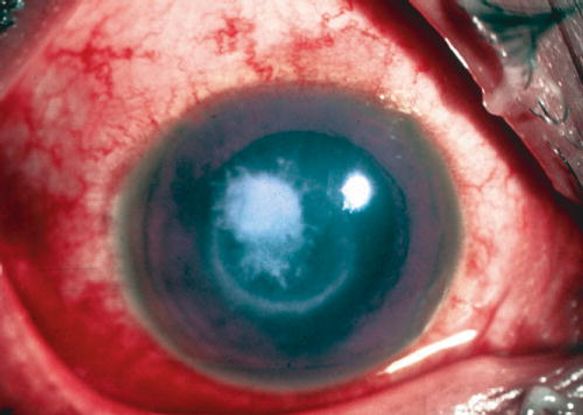

- + / - Hypopyon (Figure 12)

|

MANAGEMENT

History

- Contact lens wear

- Recent ocular trauma

- Use of ocular medications

- Recent ocular surgery

Slit-Lamp Examination

- Stain with fluorescein to assess for epithelial defects

- Assess for corneal infiltrate and record the size if present

- Assess for anterior chamber reaction

- Evert upper eyelid to check for retained foreign body

- Hypopyon

- Check intraocular pressure (IOP)

Laboratory Evaluation:

- Obtain scrapings of the corneal ulcer for microscopy and culture

- Scrape deep into the ulcer margin to obtain adequate material

- Microscopy should ideally include:

- Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) prep

- Gram stain

- Giemsa stain

- Calcufluor white (or Gomori methenamine silver)

- Various sensitivities have been reported

- Large South Indian series of studies of 1352 patients with culture-proven fungal keratitis found the following sensitivities for the detection of fungal keratitis: KOH prep 91%, calcufluor white 91.4%, gram stain 88.2%, and Giemsa stain 85.1%.

- The KOH wet mount is a simple, inexpensive, and rapid test that is easy to interpret. As such, the KOH prep (Table 1) is the preferred test in resource-poor areas.

|

Table 1. KOH prep technique and interpretation

|

|

After obtaining specimen:

- Place specimen on a clean slide.

- Add a drop of 10% KOH to the specimen.

- Cover the specimen with a cover slip, being careful to avoid air bubbles.

- Incubate for 5-10 minutes at room temperature.

- Examine saline wet mount with 10x and 40x objective to identify any budding yeast, pseudohyphae, organisms, or cells.

- Examine KOH mount with 10x for yeast pseudohyphae and 40x for smaller blastospores.

|

Fungal Cultures

- Corneal scrapings should be sent for culture in all suspected cases

- Media should include (where available):

- Blood agar (most bacteria, fungi)

- Sabouraud dextrose agar (fungi)

- Chocolate agar (Haemophilus, Neisseria)

- If cultures are negative but have high clinical suspicion, consider corneal biopsy

- In some cases, it may be necessary to proceed to penetrating keratoplasty for diagnosis and treatment (see Surgical Management below)

TREATMENT

General Concerns

- Fungal keratitis is difficult to treat and often has a long, protracted course

- Even with appropriate treatment, fungal keratitis may take weeks or months to resolve

- Daily exams are required until clinical improvement or stabilization is observed

- Close follow-up is essential and hospital admission may be necessary

- Corneal transplant may be required for severe or recalcitrant cases.

Medical Management

- The mainstays of treatment for keratomycosis are topical antifungal agents.

- Natamycin (5% topical solution) initially q1-2h, then tapered over 4-6 wks

- FDA-approved for fungal keratitis; available as ophthalmic drops

- Drug of choice for filamentous fungi

- Poor penetration limits use in deep or severe infections

- Expensive and not widely available in developing countries

- Amphotericin B (0.15-0.5% topical solution) initially q1-2h, then tapered over 4-6 wks

- Good activity against Aspergillus and Candida (Figures 12, 13)

- Not available as a topical solution – must be compounded for intravenous (IV) formulation. (50 mg of amphotericin B diluted in sterile water = 0.166%)

- Inexpensive, widely available in IV form

- Can be used via the topical, subconjunctival, intracameral, intravitreal, or intravenous route

- Voriconazole (0.5 mg/mL) q1h, then tapered over 4-6 wks

- Broad spectrum of activity against Candida, Aspergillus, Scedosporium, Fusarium, and Paecilomyces

- Difficult to obtain as topical or IM – needs to be compounded

- Dilute 1 mL of IV voriconazole (10 mg/mL) with 19 mL of sterile water;filter prior to topical administration

- Econazole (1% topical solution is available in India)

- Found to be equivalent to natamycin 5% in a randomized clinical trial (RCT) by Prajna et al

- Clotrimazole (1% topical solution is available in India)

- Other antifungals: not available as topical solutions and need to be compounded

- Miconazole

- Ketoconazole

- Fluconazole

- Recent review (2012) found no significant differences between treatment regimens and no evidence that any particular drug or combination of drugs is more effective in the management of fungal keratitis.”

- The Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial found that natamycin was associated with significantly better clinical and microbiological outcomes compared to voriconazole treatment for smear-positive filamentous fungal keratitis. This was mainly attributed to improved results with natamycin in Fusarium cases.

Surgical Management

- Epithelial debridement may help remove necrotic tissue, decrease microbial load, and improve drug penetration

- May be repeated q 24-48 hours

- Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and bandage contact lens may be used in the management of perforation or impending perforation

- Penetrating or lamellar keratoplasty is the definitive management of intractable fungal keratitis or perforating corneal ulcer

- Adequate facilities, trained practitioners, and donor material may not be available.

- Recent study reported successful outcomes after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty using acellular glycerol-preserved cornea. These grafts could prevent allograft rejection and promote graft survival rate in infected corneas.

Treatment Considerations

- Hold all topical steroids: If the patient is currently on topical steroids, they should be tapered rapidly.

- Add a cycloplegic such as scopolamine 0.25% (atropine 1% if hypopyon present)

- Systemic antifungals (p.o. fluconazole or voriconazole) may be a useful adjunct, especially in severe cases (deep ulcer, endopthalmitis)

- IOP should be checked frequently because of the risk of inflammatory glaucoma. Treat ocular hypertension if present

- Systemic ascorbic acid may be useful to accelerate corneal remodeling and healing by inhibiting polymorphonuclear cells.

- Currently the use of corneal collagen crosslinking is being evaluated and may become another option for refractory fungal keratitis.

- Inflammatory response from topical toxicity may be confused with persistent inflammation.

CASE STUDY: INDIA

History of the Present Illness

- 27-year-old male farm worker presented with eye pain, blurry vision, tearing, and red eye OS after getting hit in the left eye with something while threshing wheat

Family History

- Grandfather is blind from cataracts; a cousin is blind from trachoma

Physical Exam

- OD: wnl.

- OS: Corneal ulcer on fluorescein exam;corneal stromal infiltrate with feathery border and inflammatory ring

- 1 mm hypopyon

Laboratory Results

- Fusarium species grew from corneal scrapings within 48 hours on Sabouraud dextrose agar

Treatment

- The patient underwent a 6-week course of voriconazole 0.5 mg/mL

Follow-Up

- The patient was seen daily for the first two weeks, until clinical improvement was observed. He was then seen every three days, then weekly, until complete resolution was observed

IMAGE LIBRARY

Figure 1. Suppurative ulcerative keratitis caused by P aeruginosa. (© 2014 American Academy of Ophthalmology)

Figure 2. Ring infiltrate in Acantamoeba keratitis. (© 2014 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of Elmer Y. Tu, MD)

Figure 3. Eye with primary HSV infection shows characteristic eyelid margin ulcers. (Courtesy of Cornea Service, Paulista School of Medicine, Federal University of Sao Paulo.)

Figure 4. Atypical mycobacterial infection. Slit-lamp photograph of a patient who suffered an abrasion while doing yard work with superficial nontuberculous mycobacterial infection after chronic treatment with topical antibiotics and steroids. (Reproduced from Ophthalmology journal, Ford JG, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial keratitis in south Florida. Ophthalmology. 1998; 105(9): 1652–1658.)

Figure 5. Slit-lamp microscope photograph showing sterile melting ulcers (arrowhead) of left cornea with fluorescence staining. (Courtesy of Masters Publishing. Yin-Tsu Liu, Ko-Hua Chen, Wen-Ming Hsu. Int J Biomed Sci. 2006; 2(3): 299-301.)

Figure 6. Foreign bodies seen on the everted surface of the upper eyelid. (© 2014 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

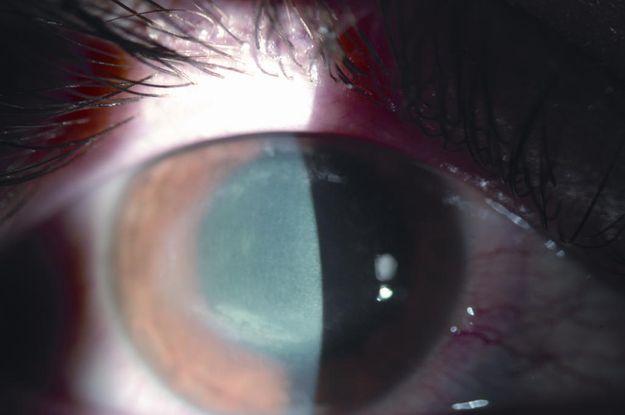

Figure 7. Early fungal keratitis resembling dendritic ulcer.

Figure 8. Fungal keratitis caused by Fusarium solanii. (© 2014 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 9. Fungal keratitis (© 2014 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of Damien Luviano, MD, FACS)

Figure 10. Fungal keratitis. (© 2014 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 11. Immune ring, with raised surface and hyphate edge, in a case of fungal keratitis. (© 2014 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

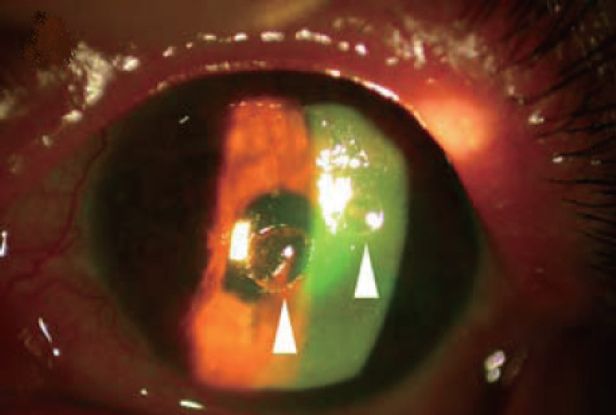

Figure 12. 43-year-old male with fungal keratitis from Aspergillus. Note the feathery edges of the infiltrate and the elevated appearance of the lesion, which are commonly seen in fungal keratitis. There is also a 1 mm layered hypopyon. (Courtesy of University of Iowa http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/atlas/pages/Fungal-keratitis-201208.html.)

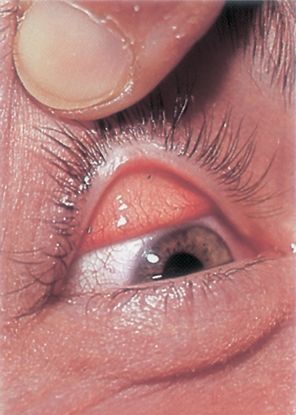

Figure 13. Subacute onset of Candida keratitis in a young adult after dust blew into her eye. A slightly “feathery” edge to stromal involvement is suggestive of fungal infection (Image courtesy of EyeRounds Online Atlas of Ophthalmology, John Chen, MD, PhD, The University of Iowa. http://www.aspergillus.org.uk/secure/image_library/other/eye9AT.jpg.)

REFERENCES

Alcaraz-Micheli L. Fungal Keratitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeWiki. Accessed May 12, 2014.

FlorCruz NV, Peczon IV, Evans JR. Medical interventions for fungal keratitis. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2012; 2: CD004241.

Gajjar DU, Pal AK, Ghodadra BK, Vasavada AR. Microscopic evaluation, molecular identification, antifungal susceptibility, and clinical outcomes in Fusarium, Aspergillus and, Dematiaceous keratitis. BioMed Res Int. 2013; 2013: 605308.

Gopinathan U, Garg P, Fernandes M, Sharma S, Athmanathan S, Rao GN. The epidemiological features and laboratory results of fungal keratitis: A 10-year review at a referral eye care center in South India. Cornea. 2002; 21(6): 555–559.

Gorscak JJ, Ayres BD, Bhagat N, Hammersmith KM, Rapuano CJ, Cohen EJ, et al. An outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens use in the northeastern United States. Cornea. 2007; 26(10): 1187–1194.

Gower EW, Keay LJ, Oechsler RA, Iovieno A, Alfonso EC, Jones DB, et al. Trends in fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001 to 2007. Ophthalmology. 2010 ; 117(12): 2263–2267.

Li Z, Jhanji V, Tao X, Yu H, Chen W, Mu G. Riboflavin/ultravoilet light-mediated crosslinking for fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013; 97(5): 669-671.

Li JL, Yu L, Deng Z, Wang L, Sun L, Ma H, Chen W. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty using acellular corneal tissue for prevention of allograft rejection in high-risk corneas. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011; 152(5): 762-770.e3.

Mascarenhas J, Lalitha P, Prajna NV, Srinivasan M, Das M, D’Silva SS, et al. Acanthamoeba, fungal, and bacterial keratitis: a comparison of risk factors and clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 157(1): 56–62.

Pfister RRL, Haddox JL, Lank KM. Citrate or ascorbate/citrate treatment of established corneal ulcers in the alkali-injured rabbit eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988; 29(7): 1110-1115.

Prajna NV, John RK, Nirmalan PK, Lalitha P, Srinivasan M. A randomised clinical trial comparing 2% econazole and 5% natamycin for the treatment of fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003; 87(10): 1235–1237.

Prajna NV1, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Prajna L, Srinivasan M, Raghavan A, Oldenburg CE, Ray KJ, Zegans ME, McLeod SD, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM; Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013; 131(4): 422-429.

Ramakrishnan TL, Constantinou M, Jhanji V, Vajpayee RB. Factors affecting treatment outcomes with voriconazole in cases with fungal keratitis. Cornea. 2013; 32(4): 445-449.

Rautaraya B, Sharma S, Kar S, Das S, Sahu SK. Diagnosis and treatment outcome of mycotic keratitis at a tertiary eye care center in eastern India. BMC Ophthalmol. 2011;11: 39.

Srinivasan M. Fungal keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004; 15(4): 321–327.

Tuli SS. Fungal keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol (Auckl NZ). 2011; 5: 275–279.

CONTRIBUTORS

Executive Editor:

R. V. Paul Chan, MD, FACS, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Section Editor:

Asia-Pacific:

Timothy Y. Lai, MBBS, MD, MMedSc, FRCS, FRCOphth, FHKAM, Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Associate Editors:

Jeff Pettey, MD, University of Utah Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, John Moran Eye Center's Residency Program Director

Grace Sun, MD, Weill Cornell Eye - Lower Manhattan, Weill Cornell Medical College Residency Program Director

Assistant Editors:

Samir Patel, BS, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Peter Coombs, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Region Contributors:

Asia Pacific:

Vishal Jhanji, Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences, Chinese University of Hong Kong

American Academy of Ophthalmology

P.O. Box 7424

San Francisco, CA 94120-7424

415.561.8500

Copyright © 2014 American Academy of Ophthalmology®. All Rights Reserved.