Yet another corneal ulcer walks in while you’re on call. What now? Follow these 10 simple tips to deal with this very common diagnosis.

1. Culture the corneal ulcer.

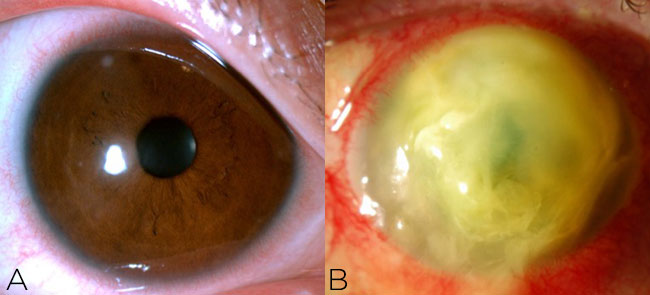

The only exception to this might be if you rupture a descemetocele. Oftentimes it is unnecessary to culture small (<2 mm) peripheral infiltrates if there are no suspicious features. All other corneal infiltrates should be scraped for diagnostic purposes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A small peripheral infiltrate (A) does not require culture, but any corneal ulcer that is large or central (B) or presents with suspicious features should be cultured.

2. Choose the right scraping tool.

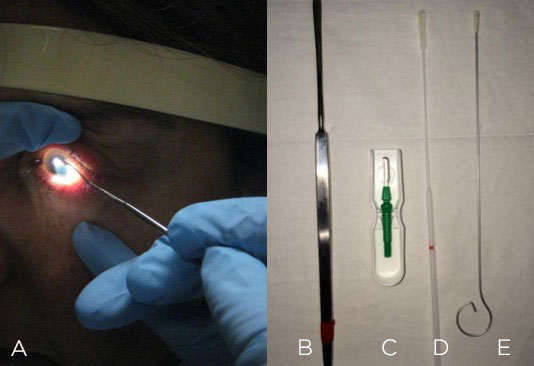

There are many choices: for example, a 67 blade, Kimura spatula or calcium alginate swab (Figure 2). If nothing else is available, you can always use a sterile cotton swab.

Figure 2. Corneal scraping (A) can be performed with a Kimura spatula (B), blade (C), culturette swab (D) or calcium alginate swab (E).

3. Don’t exclude non-bacterial causes.

Look out for suspicious features such as feathery edges, satellite lesions or endothelial plaque that may suggest fungus or yeast. A ring ulcer easily brings to mind Acanthamoeba keratitis, but the early presentation may simply be epitheliopathy with pain that’s out of proportion to the exam. Herpetic keratitis can present in many ways, but be especially wary if you see prior scars in multiple stromal planes, neovascularization, focal edema with keratic precipitates or branching dendritic staining.

Figure 3. Beware of atypical or suspicious features suggestive of fungal keratitis (A), Acanthamoeba keratitis (B) or herpetic keratitis (C).

4. Become friends with the microbiology department at your institution.

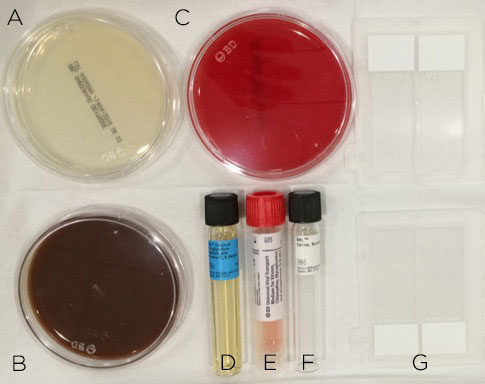

Most commonly, you will have blood, chocolate and Sabaroud agar, thioglycolate broth and viral transport media available to you (Figure 4). Make sure these are not expired or already growing colonies. In some institutions, you can submit a specimen and the plating is done in the lab. If you suspect something exotic, like mycobacteria, be aware of what culture media (e.g., Lowenstein-Jensen) is needed. (Although the media probably won’t be readily available in the clinic, you can go ahead and send the lab a swab in sterile saline.) Don’t forget to swab onto glass slides for Gram, KOH, PAS and Giemsa stains. If you are lucky, something seen on the stains will give you a clue about the diagnosis before the culture results are returned.

Figure 4. Corneal scraping should be prepared on the appropriate culture media: Saboraud agar (A) for fungal culture; chocolate agar (B) for aerobes; blood agar (C) and thioglycolate broth (D) for aerobes and anaerobes; viral transport media (E) for viral and Chylamydia culture and sterile saline (F) to transport specimens that require plating in the lab with otherwise unavailable media. Glass slides (G) should be used to create smears for microbial stains.

5. Don’t wait for positive cultures to begin therapy.

The cultures could take days to come back. Alternatively, they may finalize with no growth despite a clinical diagnosis consistent with infectious keratitis. Frequent application of topical fourth-generation fluoroquinolone is a common first-line therapy because it is readily available and covers most commonly encountered bacteria.

6. Be familiar with your compounding pharmacy.

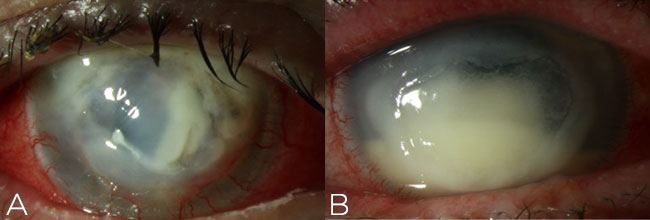

For severe ulcers that obscure the visual axis and are accompanied by stromal necrosis or hypopyon (Figure 5), consider use of fortified antibiotics. Remind the patient to refrigerate the drops. Some institutions have an in-house pharmacy to supply these; others will have you mix them yourself after hours.

Figure 5. Fortified antibiotics should be employed for severe cases of infectious keratitis, such as infiltrates resulting in stromal necrosis (A) and hypopyon (B) along the visual axis.

7. Adjust to prior treatment, if needed.

If the patient is already being treated with antibiotics or was never cultured previously, the yield of a corneal culture may be low. Nonetheless, you should still make an attempt. In addition, be sure to question the patient about whether he or she still has the contact lens from when the infection began. If so, you can culture the lens, fluid and/or case.

8. Use a positive culture appropriately.

Heavy growth is unusual for eye cultures, but does a lone colony represent true infection or simply a contaminant? Always request speciation and sensitivities, as this will help you hone and adjust the antimicrobial regimen.

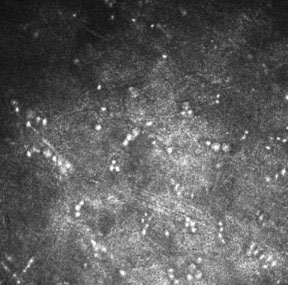

9. Use confocal microscopy or biopsy when needed.

Figure 6. Acanthamoeba cysts can be seen on in vivo confocal microscopy.

In these situations, consider confocal microscopy to look for Acanthamoeba cysts (Figure 6). You could also perform a partial-thickness corneal biopsy, which accesses deeper stromal tissue than a scraping.

10. Treat perforated ulcers carefully.

In such cases, consider the globe ruptured. If the perforation is less than 2 mm, use cyanoacrylate glue to seal the perforation. For perforations that are greater than 2 mm or have uveal or lens prolapse, surgical intervention is necessary.

* * *

About the author: Olivia L. Lee, MD, is a specialist in uveitis and cornea/external disease at the Doheny Eye Institute and assistant professor of ophthalmology at UCLA. She joined the YO Info editorial board in 2015.

About the author: Olivia L. Lee, MD, is a specialist in uveitis and cornea/external disease at the Doheny Eye Institute and assistant professor of ophthalmology at UCLA. She joined the YO Info editorial board in 2015.