George Kiyoshi Kambara, MD (1916-2001) was a first year resident in 1942 at the ENT department of Stanford Lane Hospital, San Francisco. He and his wife, a registered nurse, were both of Japanese descent. That year they each receive a letter from the United States Public Health Service informing them that they had been “selected” to serve as medical personnel at the Marysville Assembly Center - a depot for Japanese Americans established by Executive Order 9066 which asserted the government’s right to send all Japanese Americans living along the U.S. coastline into relocation or work camps.

George Kiyoshi Kambara, MD (1916-2001) was a first year resident in 1942 at the ENT department of Stanford Lane Hospital, San Francisco. He and his wife, a registered nurse, were both of Japanese descent. That year they each receive a letter from the United States Public Health Service informing them that they had been “selected” to serve as medical personnel at the Marysville Assembly Center - a depot for Japanese Americans established by Executive Order 9066 which asserted the government’s right to send all Japanese Americans living along the U.S. coastline into relocation or work camps.

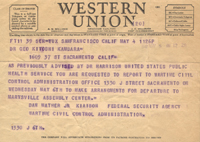

With that letter, Dr. Kambara and his wife became just two of the 120,000 Japanese Americans forced into internment camps during World War II. Like many Japanese Americans well integrated into American life, Dr. Kambara’s family was forced to sell personal property and businesses at a great loss to comply with government orders to immediately relocate.

After 6 weeks in the Marysville Assembly Center, Dr. Kambara and his wife were sent to the Tule Lake Relocation Center on the California-Oregon border. There, Dr. Kambara learned that he had been placed in charge of the camp’s eye, ear, nose and throat clinic, serving a community of 17,000 detainees. He had less than two months experience in eye work. Dr. Kambara reached out to his former ENT department and in September 1942 began a correspondence with ophthalmologist, Jerome Bettman, MD. Dr. Bettman answered questions about treatment of eye diseases through the mail and in early November he was given special permission to visit the Tule Lake Camp in what Dr. Kambara recalled as a “baptism into ophthalmology over one weekend.”

After 6 weeks in the Marysville Assembly Center, Dr. Kambara and his wife were sent to the Tule Lake Relocation Center on the California-Oregon border. There, Dr. Kambara learned that he had been placed in charge of the camp’s eye, ear, nose and throat clinic, serving a community of 17,000 detainees. He had less than two months experience in eye work. Dr. Kambara reached out to his former ENT department and in September 1942 began a correspondence with ophthalmologist, Jerome Bettman, MD. Dr. Bettman answered questions about treatment of eye diseases through the mail and in early November he was given special permission to visit the Tule Lake Camp in what Dr. Kambara recalled as a “baptism into ophthalmology over one weekend.”

In 1943, the American government began to allow Japanese Americans to move out of the internment camps and back into unrestricted areas of the country. Unfortunately, prejudice against the Japanese forced many to stay in the camps. Dr. Kambara applied for residencies around the country but found few programs willing to take him and his family. In July 1943, Dr. Kambara was given permission to relocate to the Memphis EENT Hospital and as he noted later, “the people in Memphis were wonderful to us.” Over the next 18 months, Dr. Kambara decided he wanted to concentrate in ophthalmology and eventually moved to Madison, Wisconsin to finish his studies, take his examination with the American Board of Ophthalmology, and become a fellow in the American College of Surgeons.

In 1948, Dr. Kambara was finally able to return to California where he set up a practice in Los Angeles.