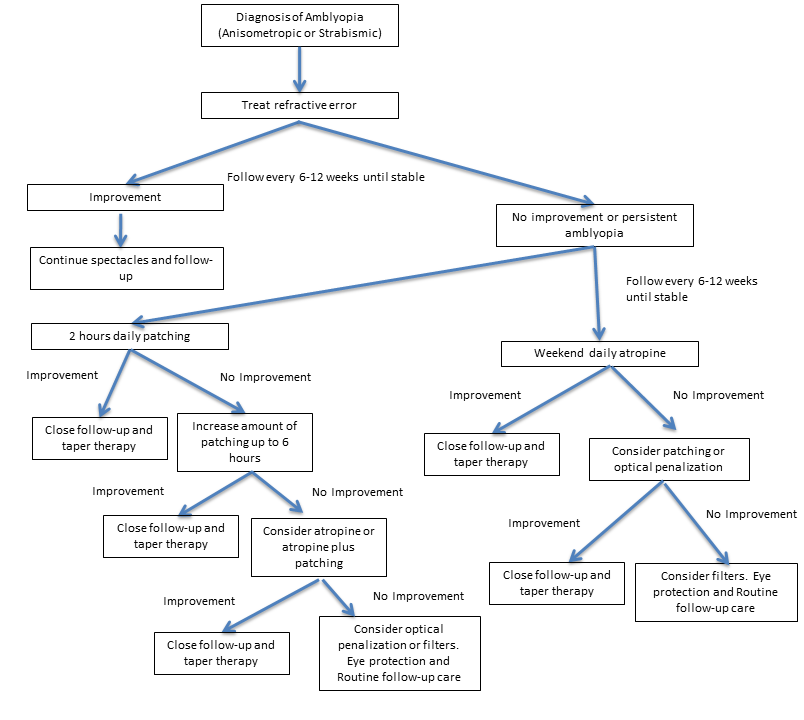

The general principle behind the treatment of amblyopia is to blur the image in the non-amblyopic eye, therefore forcing the amblyopic eye to be used for visual tasks. This has most commonly been accomplished with occlusion therapy (patching) or atropine penalization therapy. Figure 1 shows a basic amblyopia treatment algorithm, though treatment should be individualized based on family and physician preferences as well as assessment of compliance.

Figure 1. Amblyopia treatment algorithm.

A child’s brain maintains a high degree of cortical plasticity until visual maturity around the age of 9 to 10 years old. Visual plasticity is inversely related to age, therefore treatment at a younger age is more effective. However, studies have shown that occlusion and atropine therapy can be effective in adolescent children, especially if amblyopia has not been previously treated.1,2

Correction of Refractive Error

Spectacle correction alone is often the first line of therapy for amblyopia. While in the past many physicians have instituted occlusion therapy along with spectacles at the time of diagnosis, recent studies have shown that glasses alone can fully treat amblyopia in some patients. When glasses alone do not treat amblyopia fully, patching and atropine penalization are considered.

One study of patients with anisometropic amblyopia treated with glasses alone found that amblyopia improved by 2 or more lines in 77% of patients and had resolved completely in 27%.3 Other studies have demonstrated that patients with strabismic amblyopia also show significant improvement with glasses alone.4,5

The time course of improvement is variable. Some studies report an average of 14-16 weeks,3,4 while others report up to 30 weeks and beyond.3,6 Resolution of amblyopia is related to better baseline visual acuity in the amblyopic eye and smaller amounts of anisometropia.3 Patients with severe amblyopia will likely require patching.

There are several benefits of optical correction alone as the initial treatment. First, many patients will not progress to require additional therapy if amblyopia resolves with glasses alone. Second, patients who do require occlusion or penalization will start treatment with better visual acuity, which may improve compliance and therefore outcomes.

Occlusion

Occlusion therapy refers to patching the sound eye to stimulate the amblyopic eye. It is the most traditional and widely used treatment of amblyopia, though opinions vary widely on its application. Patching may be instituted at the time of amblyopia diagnosis or after a trial period of glasses alone. The dosing of patching has historically varied greatly among practitioners. Recently, the regimen has become more standardized based on several randomized amblyopia treatment trials.7,8 Many practitioners will now prescribe an initial dose of 2 hours of daily patching for strabismic or anisometropic amblyopia when visual acuity stops improving with spectacles alone. When the vision in the amblyopic eye stops improving with 2 hours of daily patching, increasing the dosage to 6 hours has been shown to be more beneficial than continuing patching at 2 hours a day.9 Visual acuity should be monitored every 6-12 weeks depending on the density of amblyopia and the age of the child.

Patching therapy can be extremely challenging and stressful for families, especially for toddlers who pull off the patch immediately after it is placed. The caregiver must understand the importance of patching in order to feel motivated to continue treatment of the child. Reward systems (eg, the child may watch TV or use electronic devices only when wearing the patch) and patching diaries with stickers can help improve compliance in older children. Clinicians should review with families the correct way of patching, applying the patch stuck with adhesive directly to the skin. When patches are instead placed on the spectacles, the child has the opportunity to look around the patch, defeating its purpose. For children who are adverse to adhesive patches or have an allergy to the adhesive, felt patches for spectacles are available with side pieces that prevent peeking.

Atropine

Atropine penalization has been used for decades as an alternative to patching therapy, but it has only recently become popular as a primary treatment for amblyopia. Atropine 1%, a cholinergic antagonist, is instilled into the non-amblyopic eye and causes pupillary dilation and reduced accommodation subsequently forcing the amblyopic eye to be used for near-vision tasks. The blurring caused by atropine is greater in hyperopic eyes because accommodation can no longer be used to obtain a clear image. In hyperopic children, the spectacle correction can be reduced to further augment the effect of atropine (see below: Optical Penalization). Historically, atropine penalization has been advocated for mild to moderate amblyopia with vision better than 20/100 because the blurring effect was considered insufficient to improve vision in severely amblyopic eyes. However, a recent study has shown that atropine does improve amblyopia even in severely amblyopic eyes (20/125 – 20/400).10

The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group (PEDIG) has played an important role in the study of atropine use in the treatment of amblyopia. In a randomized trial, atropine 1% daily was compared with 6 hours of patching in children aged 3-7 with moderate amblyopia (20/40-20/100).11,12 Researchers found similar improvements in both the patching and atropine groups, though patching showed faster improvement. Based on a parental questionnaire, atropine had a higher acceptability. Further studies have shown that weekend and daily atropine lead to similar visual acuity outcomes. 13

Comparison of Patching to Atropine for Amblyopia Treatment

|

| |

Patching |

Atropine |

| Dose |

Initially 2 hours daily |

One drop daily on weekends |

| Reversibility |

Immediate |

Effect lasts 1-2 weeks |

| Binocularity |

None |

Peripheral binocularity |

| Compliance |

Poor if child continues removes patch |

Ensured compliance once drop placed |

| Complications |

Local irritation and allergy |

Rare but serious: flushing, dry mouth, hyperactivity, tachycardia, seizures |

| Stress to child and family |

Often very high if child resists patching |

Minimal |

| Results |

Equal to atropine if compliant

|

Equal to patching but slower improvement in vision |

Optical Penalization

Both the near and distance vision of a hyperopic patient being treated with atropine penalization can be further blurred by reducing the hyperopic correction. This is referred to as “optical penalization.” In studies to date, optical penalization combined with atropine has not led to significantly better outcomes than atropine alone.14,15 However, given the small sample sizes and large confidence intervals in these studies, there may be a small benefit to augmenting atropine treatment with a plano lens over the fellow eye in those patients who stop improving with atropine alone.15 Reverse amblyopia has been described in a few patients treated with this approach, so clinicians should monitor for it. All reported cases of reverse amblyopia were reversible.

Neutral Density Filter

Although not as popular as patching or atropine for the treatment of amblyopia, Bangerter filters (Ryser Optik AF, St. Gallen, Switzerland) placed on the glasses of the non-amblyopic eye may be effective and represent a lower treatment burden compared with patching. In a study comparing part-time patching to filters, Bangerter filters did not meet the authors pre-specified criteria for non-inferiority after 24 weeks of treatment. However, because the mean visual acuity was only a half line better in the patching group and the treatment burden was lower in the filter group, the authors concluded that filters may be an effective alternative for treating moderate amblyopia in patients with poor compliance.16

Follow-Up

The Academy has proposed the following follow-up criteria in their Preferred Practice Pattern for treatment of amblyopia:17

- If the visual acuity in both eyes is unchanged, consider increasing treatment intensity or changing treatment modality, if appropriate. For example, if currently patching the fellow eye 2 hours per day, consider increasing to 6 hours per day or switching to pharmacologic penalization.

- If the visual acuity in the amblyopic eye is improved and the fellow eye is stable, continue the same treatment regimen.

- If the visual acuity in the amblyopic eye is decreased and the fellow eye is stable, recheck the refractive status, retest visual acuity, retest the pupillary examination, and assess adherence in greater depth. If there is no improvement despite good compliance, suspect an alternative diagnosis such as optic nerve hypoplasia, subtle macular abnormalities, or other anterior visual pathway disorders.

- If the visual acuity in the fellow eye is decreased, consider the diagnosis of reverse amblyopia and again recheck the refractive status of both eyes and retest visual acuity. If the diagnosis of reverse amblyopia is made, the treatment should be interrupted and follow-up should take place within a few weeks. The visual acuity should be retested to determine whether it has returned to the pretreatment level prior to resuming amblyopia therapy.

Complications of Treatment

Treatment of amblyopia is generally low risk with minimal side effects. With any of the recommended treatment modalities, reverse amblyopia is a potential risk. Reverse amblyopia is a decrease in vision of the sound eye as a result of amblyopia therapy. It can occur with both patching and atropine treatment and is usually reversible if discovered in a time. Most clinicians monitor children undergoing amblyopia treatment at least once every 2-3 months, with more frequent monitoring in younger children and those undergoing more intense occlusion regimens.

The most common side effect of atropine is light sensitivity, and therefore sunglasses are often recommended when patients are outdoors. With long-term atropine use, patients are at risk for retinal phototoxicity; however, atropine has been used long-term for the prevention of myopic progression without adverse effects on visual acuity. Allergic conjunctivitis and dermatitis are other possible local side effects. More serious systemic side effects are rare and include facial flushing, dry mouth, dizziness, tachycardia, mental status changes, and very rarely seizures. Atropine therapy should be discontinued if a patient experiences these systemic side effects.

A commonly overlooked consequence of treatment is the psychosocial impact patching therapy has on the child and caregivers. When patching is used during school, the child may be subjected to ridicule and the stigma of wearing an eye patch. When used at home, the treatment is often a struggle between the parent and child. The child may view the patch as punishment, and this could potentially damage the parent-child relationship. The studies that have evaluated the emotional impact of treatment show that patching does cause considerable stress for the child and family but that there are no long-term adverse psychological impacts on the child.18

References

- The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Randomized trial of treatment of amblyopia in children aged 7-17 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:437-47

- The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Patching vs atropine to treat amblyopia in children aged 7 to 12 years. Arch Ophthaomol. 2008;126:1634-42.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Treatment of anisometropic amblyopia in children with refractive correction. Ophthalmology. 006;113:895-903.

- Stewart CE, Moseley MJ, Fielder AR, et al. Refractive adaptation in amblyopia: quantification of effect and implications for practice. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1552-6.

- Cotter SA, Foster NC, Holmes JM, et al; Writing Committee for the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Optical treatment of strabismic and combined strabismic-anisometropic amblyopia. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:150-8.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial to evaluate 2 hours of daily patching for strabismic and anisometropic amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:904-12.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of patching regimens for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:603-11.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial to evaluate 2 hours of daily patching for strabismic and anisometropic amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:904-12.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of increasing patching for amblyopia. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2270-77.

- Repka MX, Kraker RT, Beck RW, et al. Treatment of severe amblyopia with weekend atropine: Results from 2 randomized clinical trials. J AAPOS. 2009;13:258-63.

- The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of atropine vs patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:268-78.

- The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Two-year follow-up of a 6-month randomized trial of atropine vs patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. 2005;123:149-57.

- The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of atropine regimens for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2076-85.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Pharmacological plus optical penalization treatment for amblyopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 009;127:22-30.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of adding a plano lens to atropine for amblyopia. J AAPOS. 2015;19:42-48.

- The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial comparing bangerter filters and patching for the treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:998-1004.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Panel. Amblyopia. Preferred Practice Pattern. 2012.

- Hrisos S, Clarke MP, Wright CM. The emotional impact of amblyopia treatment in preschool children. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1550-56.