While many common ocular surface diseases can be managed well with medical therapy, there are times when medical management just isn’t enough or appropriate. This article discusses several ocular surface disorders that a comprehensive ophthalmologist can treat with surgical procedures performed in the office or minor surgery setting. Performing these procedures is rapid, straightforward, has a low risk of complications and can often delay or prevent the need for more aggressive surgeries.

Curettage of molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum are dome-shaped, viral, wart-like skin lesions. When located near the eyelid margin, the viral particles can cause chronic follicular conjunctivitis.

While molluscum is often a self-limited condition, it can be prolonged and quite dramatic in some cases, such as immunocompetent individuals,.

There are numerous treatment options for molluscum lesions, including cautery, cryotherapy and shave biopsy. However, simple curettage is easy to perform and usually successful and relatively painless for the patient. In cooperative patients, it can be done without anesthesia at the slit lamp.

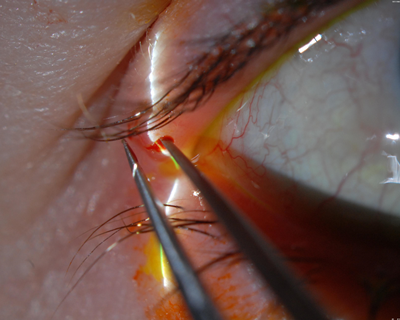

Using a small chalazion scoop or my preference, a jeweler’s forceps, the central core of the molluscum is carefully removed. I am fairly aggressive, as the goal is to cause a small amount of bleeding (Figure 1).

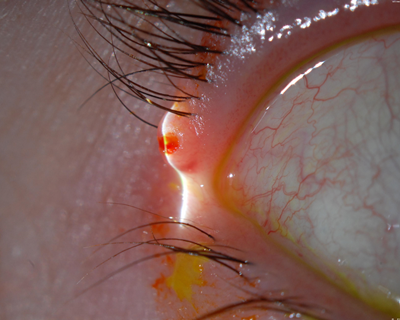

Figure 1: a) Molluscum contagiosum lesion of the right upper eyelid near the lateral canthus. b) Jeweler’s forceps reaching deep into a molluscum contagiosum lesion aggressively enough to cause a small amount of bleeding. c) At the end of the procedure, the molluscum contagiosum lesion is left to involute over several weeks.

This direct lesional trauma is thought to induce an immune response that causes the lesion to disappear over several weeks. Resolution of the follicular conjunctivitis often takes a bit longer, around 4 to 6 weeks.

Smoothing out shield ulcers

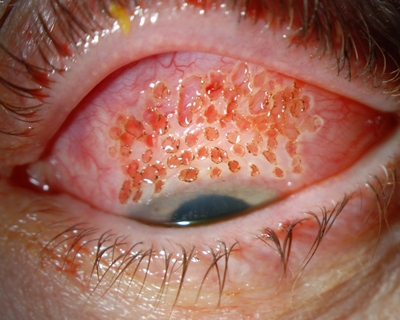

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis often presents with giant papillae under the upper eyelid. There is also a variant with limbal follicles. The giant papillae can cause trauma to the corneal surface, inducing a corneal epithelial defect, which can evolve into a shield ulcer.

Depending on the severity of the condition, numerous topical medical treatments can be used, including allergy medications, such as anti-histamines/mast cell stabilizers, cyclosporine, steroids and antibiotics. Systemic allergy medications may also be helpful.

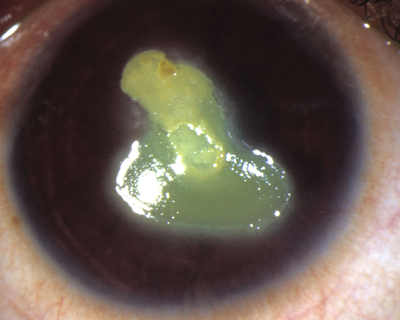

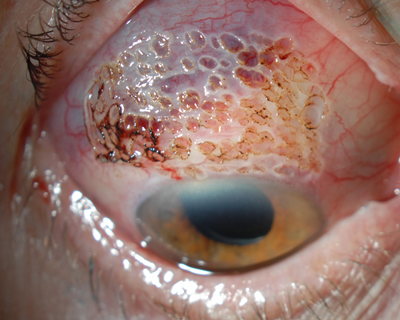

Shield ulcers with smooth stroma can heal with medical therapy. However, the surface of some shield ulcers develop a fibrotic or calcified appearance; in my experience, this type of shield ulcer does not heal without surgical debridement, which can be performed easily at the slit lamp.

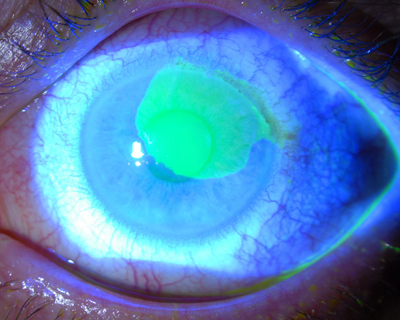

After placing topical anesthetic drops and an eyelid speculum in the eye, a #15 blade can be used to aggressively scrape off the abnormal material with the goal of reaching a smooth (or relatively smooth) Bowman’s layer, which is often somewhat hazy (Figure 2).

Figure 2: a) A chronic shield ulcer unresponsive to medical therapy in a 12-year-old girl with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Note the elevated calcified fibrotic surface. b) Immediately after the lesion was debrided with a #15 blade, the surface was much smoother. It epithelialized within a week with significant improvement in corneal clarity and visual acuity.1

Once smooth, use either frequent ointment application, a bandage soft contact lens or a nonsecured amniotic membrane to help heal the epithelial defect. These initial therapy options should also be considered long-term treatment.

Burning off superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) can be an extremely frustrating condition for both patients and doctors. The classic history is months to years of dry eye/blepharitis symptoms that do not respond to conventional therapy.

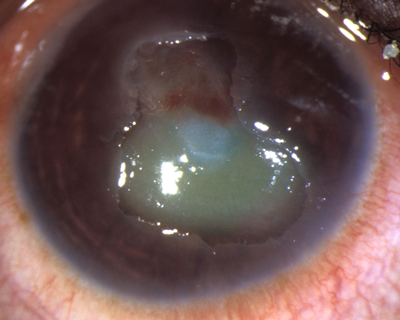

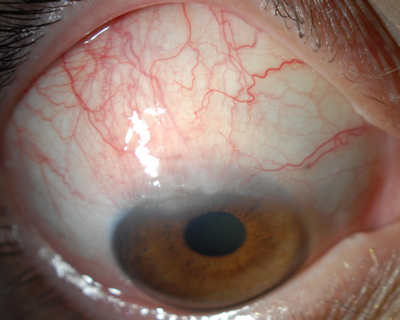

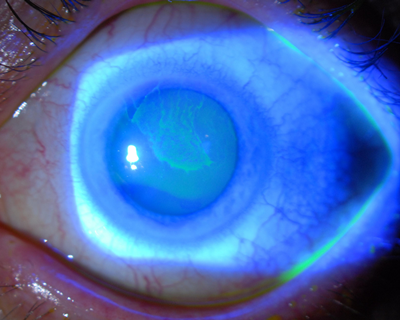

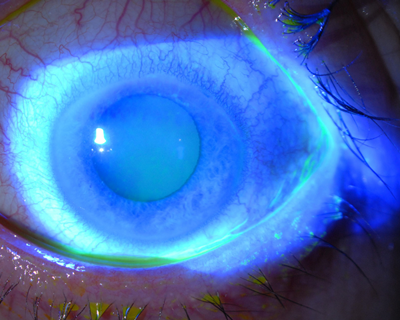

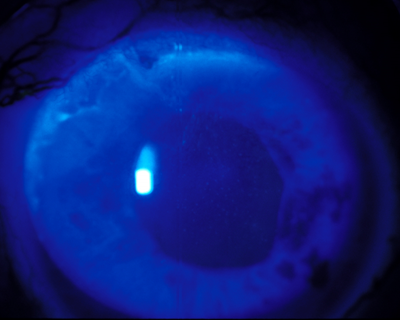

The key to making the diagnosis is to make sure to evaluate the superior conjunctiva. SLK will typically demonstrate a leash of thickened, inflamed bulbar conjunctiva superiorly, fine papillae of the superior palpebral conjunctiva and often superior corneal neovascularization and filaments. (Figure 3).

Figure 3: a) Significant superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis causing thickened bulbar conjunctiva, superior corneal pannus and neovascularization. b) Note the localized lissamine green dye staining of the superior bulbar conjunctiva.

Medical treatment includes topical preservative-free lubrication, mast cell stabilizers, cyclosporine and steroids but is often ineffective. Punctal occlusion may be helpful. Conjunctival recession or resection may be effective but is generally performed in the operating room.

However, localized conjunctival cautery can take place in the office in cooperative patients and can significantly improve SLK symptoms. To perform this surgery, I place an eyelid speculum and anesthetic drops in the eye and then inflate the superior bulbar conjunctiva with local lidocaine on a tuberculin syringe.

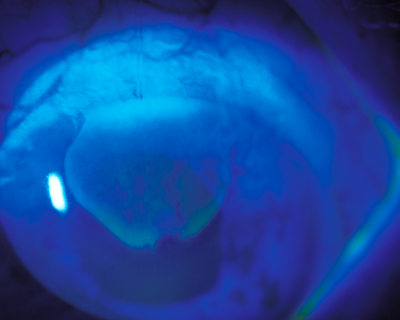

With a hand-held battery-operated cautery unit, I apply 50 to 100 burns to the area of SLK, taking great care to burn just the conjunctiva and not the sclera (Figure 4).

Figure 4: a) Immediately following a localized cautery treatment of the superior bulbar conjunctiva in a middle-aged woman. b) Immediately after a somewhat more extensive localized cautery treatment of the superior bulbar conjunctiva in an elderly woman.

I treat the burns with an antibiotic ointment. They heal within a week, tighten up the conjunctival tissue and improve SLK symptoms. In my experience, the symptomatic improvement can last for years, but the procedure can also be repeated if symptoms recur.

Debridement for partial limbal stem cell deficiency

Another simple office procedure, selective epithelial debridement, can be used to treat partial limbal stem cell deficiency.

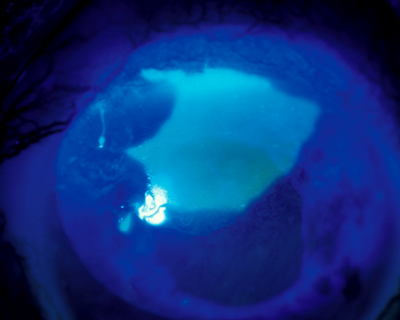

Some patients have a localized area of damaged corneal limbal stem cells that cause irregular epithelial cells to grow onto the cornea. Common etiologies include long-term contact lens wear and prior ocular surgery. These abnormal epithelial cells are less adherent than normal corneal epithelial cells, which can lead to recurrent erosions, and if these cells reach into the visual axis, they can adversely affect vision.

After application of topical anesthesia and placement of an eyelid speculum, I easily debride the abnormal epithelium all the way to the limbus with a cellulose sponge and a #15 blade (Figures 5 and 6). Then I treat the area with topical antibiotics and a bandage soft contact lens.

Figure 5: a) An extensive tongue of abnormal epithelium due to limbal stem cell damage has crossed the visual axis and caused poor vision in this long-term soft contact lens wearer. b) A large epithelial defect is present immediately after selective epithelial debridement in this eye. c) Three days after debridement, the epithelial defect has healed and filled in with normal, smooth corneal epithelial cells, and corrected vision improved to 20/20.

Figure 6: a) A leash of abnormal epithelium due to superior limbal stem cell deficiency is reaching into the visual axis and beginning to cause visual symptoms. b) The epithelial defect is healing nicely 1 day after selective epithelial debridement in this eye. c) Eleven days after the procedure, the epithelial defect has completely resolved with normal, smooth corneal epithelium centrally. There is a small amount of recurrent abnormal epithelial cells at the superior limbus.

The concept is to remove the abnormal cells, which allows normal corneal epithelium to grow in from the corneal side. Since success relies on the presence of some normal corneal epithelium, the procedure is not successful in eyes with total limbal stem cell deficiency.

Abnormal cells will again grow in from the limbus, as this procedure doesn’t treat the actual limbal stem cell deficiency. Generally, most of the epithelial defect will be replaced by healthy epithelium, but there is usually a small area of recurrent abnormal epithelium near the limbus.

As long as normal epithelium covers the pupil, the patient’s vision should improve significantly. If a large area of abnormal epithelium has grown back, either soon after the procedure or years later, selective epithelial debridement can be repeated. I am frequently amazed by how long the beneficial effects of a single procedure can last.

Adding to your armamentarium

While medical therapies for ocular surface diseases commonly seen in clinical practice are the first line of treatment and often successful, minor surgical procedures, like those discussed here, can be quite beneficial for some conditions when they don’t respond to medical treatment. Ophthalmologists should consider adding them to their treatment armamentarium.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Rapuano is a consultant for Allergan, Bausch & Lomb/Valeant, Bio-Tissue, Nicox/Valeant, Shire, TearLab and TearScience. He serves as a lecturer for Bausch & Lomb/Valeant, Bio-Tissue and TearScience. He owns stock in Rapid Pathogen Screening, Inc.

References

- Ozbek Z, Burakgazi AZ, Rapuano CJ. Rapid healing of vernal shield ulcer after surgical debridement: A case report.Cornea. 2006;25(4):472-473.