Two patients with advanced neovascular AMD have regained reading ability after receiving a specially engineered patch of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells derived from stem cells.

"We've restored vision where there was none,” lead investigator Lyndon da Cruz, MD, told the BBC. Dr. da Cruz is a consultant retinal surgeon at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London and first author on the paper, which appeared in Nature Biotechnology on March 19, 2018.

The team is the first to use a human embryonic stem cell (hESC)–derived RPE monolayer to treat AMD. In one previous stem cell study, Japanese scientists relied on induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which minimize the risk of rejection but must be harvested from individual patients and grown for a lengthy period before they can be used.

It’s exciting that the hESC-treated patients—a woman in her early 60s and a man in his 80s—did not require systemic immunosuppression, says Ajay Kuriyan, MD, a retina specialist and assistant professor at the Flaum Eye Institute in Rochester, NY. Instead, the patients received local therapy—an intravitreal fluocinolone implant—and neither showed signs of rejection.

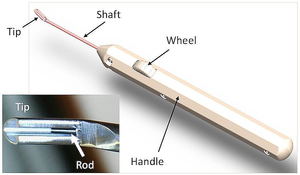

Researchers grew the commercially available hESCs on a coated synthetic membrane, creating a rigid structure that could be inserted through a small opening in the retina. Surgeons used a custom microsurgical tool (shown in the image) to steer a 6 x 3-mm patch to a subretinal space under the fovea. The procedure took less than 2 hours. Afterward, one patient experienced retinal detachment and the other had an exposed suture.

Researchers grew the commercially available hESCs on a coated synthetic membrane, creating a rigid structure that could be inserted through a small opening in the retina. Surgeons used a custom microsurgical tool (shown in the image) to steer a 6 x 3-mm patch to a subretinal space under the fovea. The procedure took less than 2 hours. Afterward, one patient experienced retinal detachment and the other had an exposed suture.

Over the next 6 months, the authors used OCT to monitor the patch’s growth as the stem cells proliferated and spread outward, then stabilized.

The patients gained an “impressive” 29 and 21 letters, respectively, during the 12 months of follow-up, says Dr. Kuriyan. The Japanese study using iPSCs was effective in halting chronic AMD progression but that treatment did not improve vision.

It’s worth noting, however, that this new study included patients with acute submacular hemorrhage, which could have a different etiology from patients with more chronic vision loss.

“That may be part of why the vision improvement was greater than previous stem cell studies, and may not necessarily mean that this implant works better,” says Dr. Kuriyan, adding that patients with submacular hemorrhage have varying visual outcomes with different treatment regimens, including anti-VEGF with or without displacement of the hemorrhage.

Larger, longer studies are needed before researchers can weigh the pros and cons of various stem cell treatments for blindness, he says.