EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- Congenital glaucoma is a heterogeneous group of diseases with the following classifications based on age:

- Congenital glaucoma (~40% of cases) is existent or becomes evident at birth.

- Infantile glaucoma (~50% of cases) becomes evident during early childhood (<3 years old).

- Juvenile glaucoma (~10% cases) becomes apparent in later childhood (>3 years old).

- The incidence of primary congenital glaucoma (PCG) is about 1 in 10,000–18,000 live births and depends heavily on ethnic origin.

- PCG is highly prevalent in inbred populations and consanguinity is strongly associated with the disease (Elder MJ, 1993).

- Glaucoma-induced blindness in children is responsible for 18% of children in blind institutions and 5% of pediatric blindness worldwide (Gilbert et al, 1994).

- In general, males are more affected than females (Ellong et al, 2007; Das et al, 2001).

- In 75% of cases, both eyes are affected.

- Ninety percent of cases occur sporadically, and only 10% of cases have an increased frequency in their family, mostly with an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance.

- Penetrance varies in the range 40%–100%.

Regional Information (SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA)

- One report from Cameroon using a hospital-based sample estimated a prevalence of 0.4% for juvenile glaucoma (Ellong et al, 2007).

- Another hospital-based study from Ethiopia estimated that PCG accounted for 2% of all glaucoma cases (Melka et al, 2006)

- In Nigeria and most of Africa, the majority of children with PCG present late with advanced disease as evidenced by large corneal diameters and cloudy corneas.

- In a study done in Ethiopia, patients were diagnosed and treated at a relatively late age (mean, 3.3 years; range, 0.4–10 years) (Ben-Zion et al, 2011).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- For the classic triad of epiphora, photophobia, and blepharospasm:

- Nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- Conjunctivitis

- Uveitis

- For corneal clouding and edema:

- Corneal dystrophies

- Dysgenesis of the anterior segment (Peters anomaly, sclerocornea, congenital anterior staphyloma)

- Corneal dermoids

- Corneal abrasion, forceps trauma

- Keratitis

- Posterior corneal defects (posterior keratoconus)

- Metabolic disorders, such as mucopolysaccharidoses or cystinosis

- Aniridia

- For buphthalmos

- High axial myopia

- Megalocornea

- For optic nerve cupping

- Physiologic cupping

- Optic nerve coloboma

- Optic nerve atrophy

- Optic nerve hypoplasia

- Optic nerve malformation

- Optic nerve pit

- Megalopapilla

- Morning-glory papilla

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DEFINITION

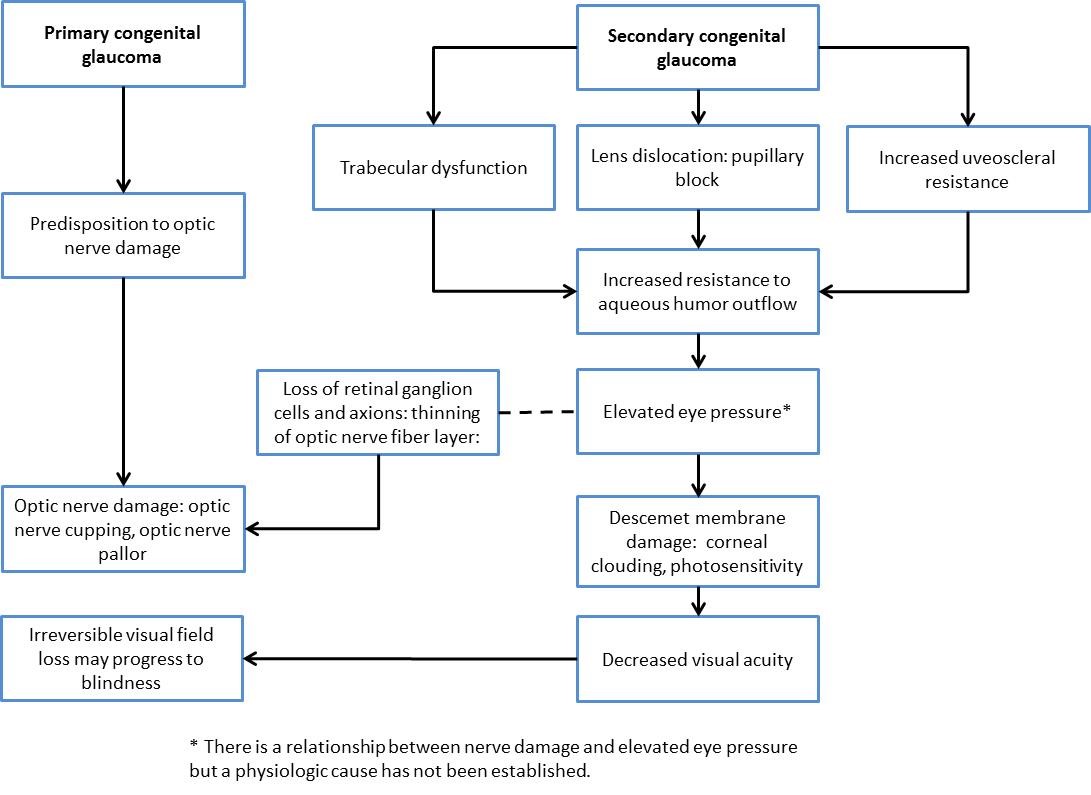

Chart 1. Pathophysiology of primary and secondary congenital glaucoma.

- Abnormalities in anterior chamber development lead to the obstruction of the outflow of aqueous humor. There are several theories of pathogenesis :

- Anomalous trabecular meshwork development (neural crestopathy)

- Barkan membrane covering the trabecular meshwork

- Anterior insertion of the ciliary body (due to arrest in normal migration of the uvea) may contribute to narrowing or collapse of Schlemm canal

- Absent Schlemm canal

- Resistance to the flow of aqueous causes intraocular pressure (IOP) to rise.

- The rise in IOP then induces a decline in viable retinal ganglion cells, just as in adult glaucoma, which leads to damage of the visual field and eventually a decline of visual acuity.

- Causes for these developmental abnormalities can be primary like genetically founded abnormalities of the outflow pathways or secondary due to tumors, traumas, systemic medication, or inflammation, or following cataract extraction (Table 2).

- Congenital glaucoma involves increased intraocular pressure and associated atrophy of the optic nerve with subsequent functional impairment.

- Primary congenital glaucoma is the result of isolated abnormal development of the anterior chamber angle structures Figure 1.

- Secondary congenital glaucoma is associated with a variety of ocular and systemic syndromes and with surgical aphakia (absence of the lens).

|

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Associations with Congenital Glaucoma

|

|

Primary

|

Incomplete development of trabecular meshwork in embryogenesis:

- Autosomal recessive: CYP1B1 (2p21), GLC3B (1p36) and GLC3C on (14q24.3)

- Autosomal dominant: GLC1A TIGR/myocele gene (MYOC)

|

|

Secondary

|

Associated with congenital disease:

- Aphakia (most common form of pediatric glaucoma)

- Trisomy 13-16 (Patau syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), trisomy 21, Turner (XO/XX)

- Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome

- Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous

- Stickler syndrome (hereditary progressive arthro-ophthalmopathy)

- Zellweger (cerebrohepatorenal syndrome)

- Hallermann-Streiff syndrome (dyscephalic mandibulo-oculofacial syndrome)

- Oculodentodigital dysplasia

- Prader-Willi syndrome

- Cockayne syndrome

Iridotrabeculodysgenesis: aniridia

Phakomatoses:

- Sturge-Weber syndrome/encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis on eye with port-wine mark (Figure 2). Syndrome includes cerebral calcifications, seizures, developmental delay.

- Neurofibromatosis 1 with glaucoma and Lisch nodules on glaucomatous eye

- Angiomatosis retinae et cerebelli

- Oculodermal melanocytosis

Iridocorneal trabeculodysgenesis:

- Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome and Peter anomaly

- Systemic hypoplastic mesodermal dysgenesis (Marfan syndrome or Weill–Marchesani syndrome)

Associated with metabolic disease:

- Lowe/oculocerebrorenal syndrome: X-linked recessive syndrome with bilateral disciform cataracts, renal tubular dysfunction, developmental delay and glaucoma

- Homocystinuria

Associated with mitotic disease:

- Juvenile xanthogranuloma (nevoxantho endothelioma)

- Retinoblastoma

Infections and other:

- Congenital rubella

- Herpes simplex iridocyclitis

- Maternal use of topiramate

- Fetal alcohol syndrome

|

SIGNS/SYMPTOMS

Signs

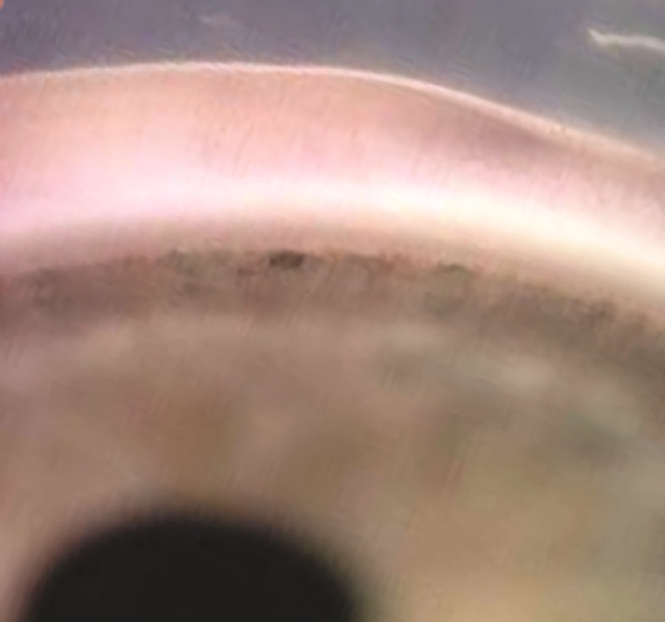

- Enlarged optic cupping (cup to disc ration >0.2) and/or asymmetric cupping (Figure 3)

- Newborn IOP >10–12 mmHg

- Anterior insertion of the iris and Barkan membrane

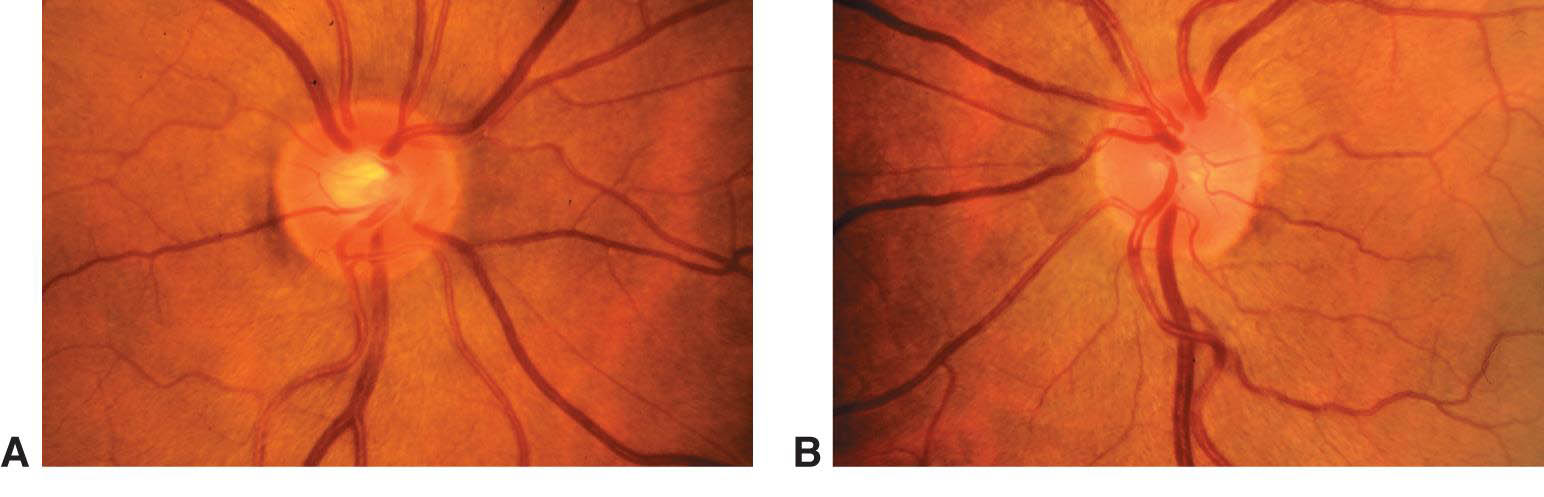

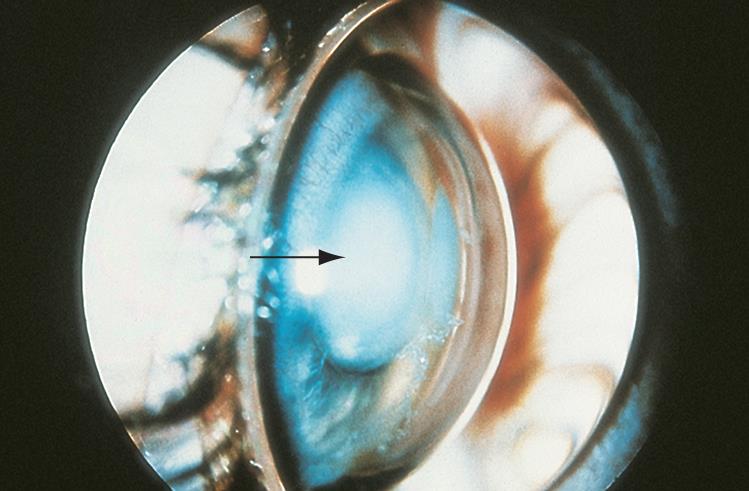

- Haab-striae (cracks in Descemet membrane, Figure 4)

- Increased horizontal corneal diameter (above 11mm in first year of life, above 13 mm thereafter)

Symptoms

- Triad

- Epiphora

- Photophobia

- Blepharospasm

- Corneal opacities (Figure 5)

- Buphthalmos (Figure 6)

- Aniridia (increased IOP and glaucoma frequently due to blockade of outflow pathway by hypoplastic iris stump) (Figure 7)

- Iris heterochromia

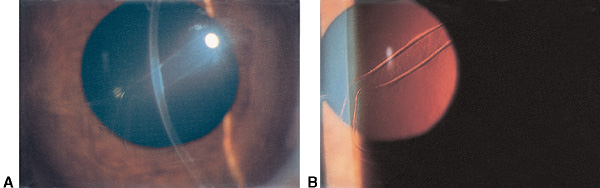

- Ectopia lentis (Figure 8)

- Nystagmus

- Microcystic edema

- In severe, untreated cases, lens dislocation and globe perforation

Note: Normal gonioscopy differences in all infants include trabecular meshwork more lightly pigmented, Schwalbe line less distinct, and uveal meshwork translucence (Figure 9).

MANAGEMENT

The treatment of congenital glaucoma needs a team approach to normalize IOP, correct existing errors of refraction and anterior segment architecture and to enable physiologic maturation of the visual pathway to achieve as much vision as possible in the affected cases. If treated promptly and aggressively, useful vision may develop, which in most cases is far from physiological but much improved compared to decades before when PCG lead to blindness in nearly all cases.

- Generally, the preferred mode of treatment for congenital glaucoma is surgical not medical.

- Topical medication is rarely effective.

- Compliance cannot be expected to be very high in a life-long disease that may lead to blindness.

Examination Under Anesthesia

- To confirm glaucoma and find the appropriate diagnosis

- Measurement of IOP

- Thorough examination of all parts of the eye

- Depending on the correct diagnosis, further surgical treatment is planned.

Surgical Treatment

First-line treatment:

- Goniotomy and trabeculotomy (collectively, “angle surgery”) is the preferred treatment: ~90% success rate

- Goniotomy is performed when the cornea is clear and there is a clear view of angle structures.

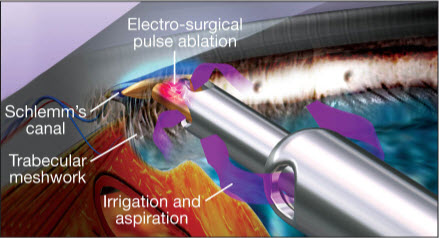

- Trabeculotomy (Figure 10) is performed when the cornea is cloudy.

- 50%–95% success rate; difficult because of higher risk for infection, flat anterior chamber, and hypotony (eye-rubbing)

Treatments for patients in whom angle surgery is not adequate:

- Trabeculectomy with mitomycin C: 67%–87% success at 1 year, but 58%–59% success at 2 years

- Combination trabeculotomy/trabeculectomy

- Molteno, Baerveldt, and Ahmed device implantation (glaucoma drainage devices, Figure 11): 50%–85% success with IOP-lowering drops

Treatments for challenging cases that have failed multiple, more conservative treatments, and cases with limited visual potential:

- Cyclodestructive procedures

- Cyclocryotherapy: 33% success with high complications, suitable for cases with altered anterior segment architecture due to repeated glaucoma surgery

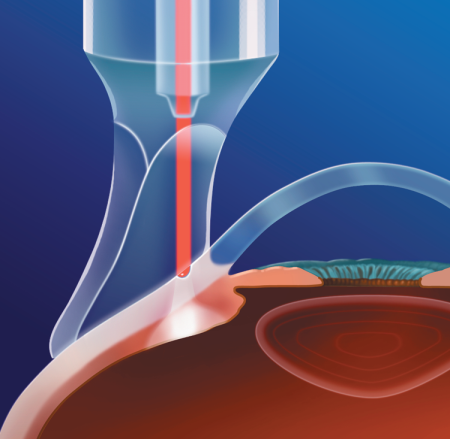

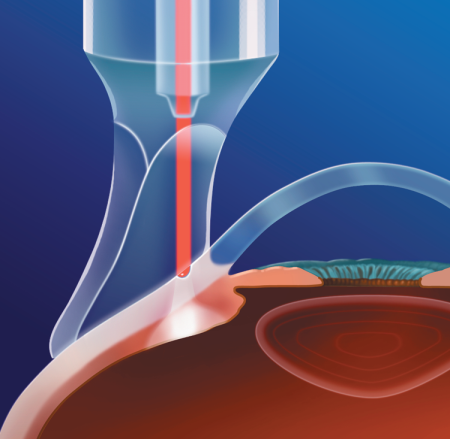

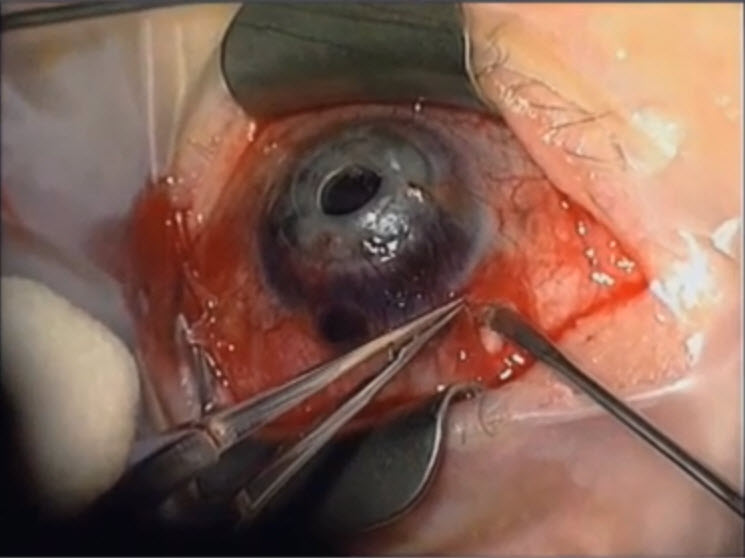

- Transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation; 50% success in refractory glaucomas (Figure 12 and Figure 13)

- Endolaser cyclophotocoagulation: 50% success (Figure 14)

- Cycloablation/YAG for resistant cases

Medical Management

Medical management is preferred only in selected cases and as temporary treatment:

- Oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (eg, acetazolamide and methazolamide) are most effective.

- Topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (eg, dorzolamide 2%, brinzolamide 1%) are less effective at lowering IOP but have fewer systemic side effects.

- Topical beta-blockers (timolol 0.25%, levobunolol 0.25%, betaxolol) have been used for 30+ years.

- Can cause respiratory distress, caused by apnea or bronchospasm, and bradycardia

- Combination drops such as timolol/dorzolamide (Cosopt) may increase compliance in children requiring more than one topical agent to control IOP.

- Prostaglandin analogs (latanoprost 0.005%, travoprost 0.004%, bimatoprost 0.03%) are not for uveitic glaucoma and can cause iris pigmentation and eyelash growth.

- Pilocarpine miotics are rarely used.

- The α2-adrenergic agonist apraclonidine should be used only for the short term.

- The α2-adrenergic agonist brimonidine use is limited for systemic effects and is absolutely contraindicated in children less than 2 years of age. It should be used with caution in young children until 8 years old.

Additional Treatment

- Spectacles for refractive error

- Treat amblyopia and strabismus

- Tinted (or transition) lenses (may help with photophobia)

- Frequent cycloplegic refraction (every 4–6 months) often necessary with rapid IOP changes

Regional Information (Sub-Saharan Africa)

- Most patients present late with advanced stages of disease evidenced by corneal opacities, precluding goniotomy in most cases.

- Recently, combined trabeculotomy/trabeculectomy has been used in these patients.

- For older children in whom a second trabeculectomy has failed, glaucoma drainage using the Ahmed glaucoma drainage device is available.

- Initial medical therapy often with timolol 0.25% in infants is offered in the interim while awaiting surgery.

CASE STUDY

History of Present Illness

Baby Jones was born at full term with no complications during his gestation. At 1 month after delivery, the mother noticed that his eyes were watering, and he appeared to not like bright lights. She noticed that at times it seemed as if he would squeeze his eyes shut. The baby’s pediatrician noticed that his corneas appeared cloudy, and he was referred to an ophthalmologist.

Examination

The ophthalmologist found an elevated intraocular pressure, an increased corneal diameter of 15mm, and microcystic edema with Haab striae. On dilated fundus exam, the child’s optic nerve heads appeared normal.

Treatment

He was started on a topical prostaglandin analog. IOP was reduced below 12mmHg in both eyes. He was then referred to an ophthalmological center with experience in congenital glaucoma treatment. After a thorough examination under anesthesia, goniotomy was performed in the right eye and at a later point in time in the left eye. On further examinations, though IOP was normal, a mild amblyopia was detected in the left eye, probably due to an anisometropic refractive error. Patching was carried out and the refractive error was treated with glasses. Baby Jones is now 11 years old and has a visual acuity of 20/80 in his right eye and 20/200 in his left eye. He attends a special school.

IMAGE LIBRARY

Pathophysiology/Definition

Figure 1. Typical appearance of the anterior chamber angle of an infant with congenital glaucoma.

(© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org. Courtesy of Ken K. Nischal, MD.)

Signs/Symptoms

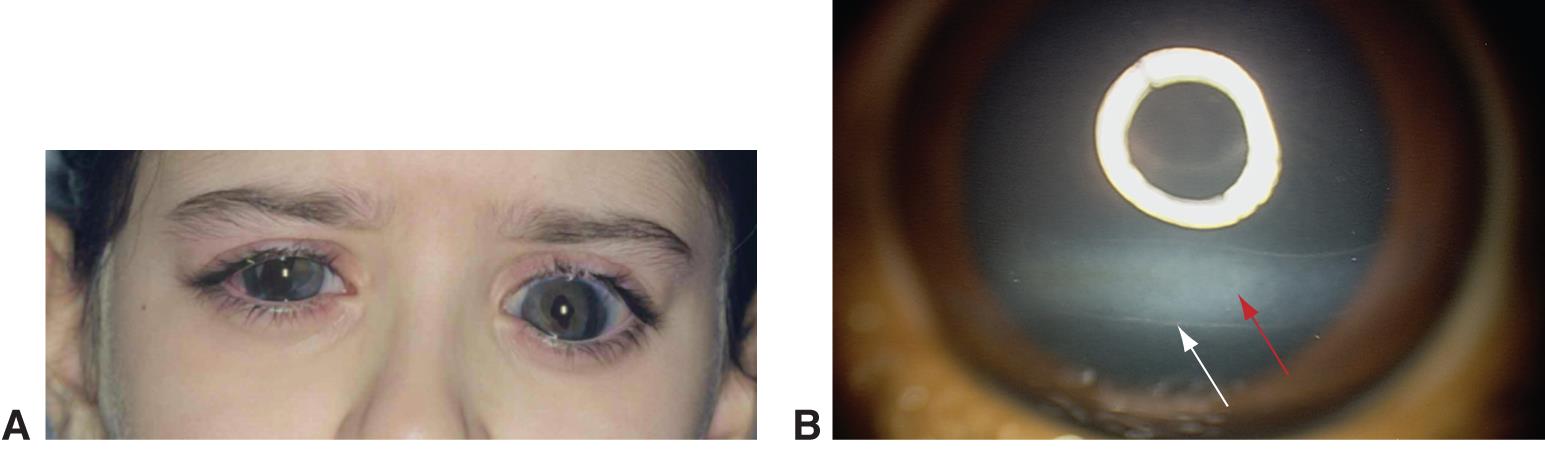

Figure 2. Sturge-Weber syndrome. A. Sturge-Weber syndrome with increased tortuosity of limbal blood vessels due to elevated venous pressure leading also to an increase in intraocular pressure. B. Sturge-Weber syndrome classically comprises the triad of port-wine facial telangectasias (nevus flammeus) in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve that respects the vertical midline, ipsilateral glaucoma, and intracranial angiomata. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org).

Figure 3. Asymmetry of optic nerve cupping. Note the generalized enlargement of the cup in the right eye (A) as compared with the left eye (B). Asymmetry of the cup–disc ratio of more than 0.2 occurs in less than 1% of individuals without glaucoma. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 4. Haab striae. A. Haab striae in Descemet membrane. B. Better seen with retroillumination. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 5. Corneal clouding. Right eye demonstrates cloudy and enlarged cornea in this infant with congenital glaucoma. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 6. Buphthalmos. A. Buphthalmos in a child with a history of congenital glaucoma. B. Haab striae with corneal edema and opacification. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 7. Aniridia in an infant. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 8. Ectopia lentis. Anterior displacement of the lens into the anterior chamber resulting in iris bombe and shallow anterior chamber. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 9. The anterior chamber angle of a normal infant’s eye, as seen by direct gonioscopy with a Koeppe lens. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org. Courtesy of Ken K. Nischal, MD.)

Figure 10. Example of handpiece (Trabectome) used in microsurgical management of adult and infantile glaucoma. (Image courtesy of NeoMedix Corp.)

Figure 11. Examples of glaucoma drainage devices (aqueous shunts). A. Single-plate (left) and double-plate (center and right) Molteno implants. B. Baerveldt glaucoma implants: 250 mm2 (left), 350 mm2 (center), and 425 mm2 (right). C. Krupin eye valve with disk, D. Ahmed glaucoma valve. (Reproduced, with permission, from Sidoti P. “Aqueous Shunting Procedures.” Focal Points: Clinical Modules for Ophthalmologists. American Academy of Ophthalmology, No. 3, 2002.)

MANAGEMENT

Figure 12. Cyclophotocoagulation. Probe handpiece attachment, which facilitates orientation parallel to visual axis. (Courtesy of Iridex.)

Figure 13. Transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation being performed in a child with congenital glaucoma refractive to other treatments. Transillumination probe being utilized to aid in the correct localization of ciliary body. (Reproduced from Morales J, et al. Current surgical options for the management of pediatric glaucoma. Journal of Ophthalmology. Hidawi Publishing: 2013.)

Figure 14. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation in a case where a tube shunt may be failing . (Reproduced from video. Subspecialty Day 2012: Pediatric Ophthalmology, David A. Plager, Advances in Glaucoma Care: New Technologies in Pediatric Glaucoma.)

REFERENCES

Al-Obeidan SA, Osman Eel-D, Dewedar AS, Kestelyn P, Mousa A. Efficacy and safety of deep sclerectomy in childhood glaucoma in Saudi Arabia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;92(1):65–70.

Aponte EP, Diehl N, Mohney BG. Incidence and clinical characteristics of childhood glaucoma: a population-based study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(4):478–82.

Banchio C, Castro RI. Ceguera infantil en la provincia de Neuquén. Médico Oftalmól. 2008;21(5):38–40.

Ben-Zion I, Tomkins O, Moore DB, Helveston EM. Surgical results in the management of advanced primary congenital glaucoma in a rural pediatric population. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(2):231–5.

Bhattacharjee H, Das K, Borah RR, et al. Causes of childhood blindness in the northeastern states of India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56(6):495–9.

Das J, Bhomaj S, Chaudhuri Z, Sharma P, Negi A, Dasgupta A. Profile of glaucoma in a major eye hospital in North India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2001;49(1):25–30.

Dorairaj SK, Bandrakalli P, Shetty C, RV, Misquith D, Ritch R. Childhood blindness in a rural population of southern India : prevalence and etiology. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(3):176–82.

Ellong A, Ebana Mvogo C, Nyouma Moune E, Bella-Hiag A. Juvenile glaucoma in Cameroon. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;305:69–77.

Elder MJ. Congenital glaucoma in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:413–416.

Friedberg M, Rapuano C. Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 5th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

Genĉík A. Epidemiology and genetics of primary congenital glaucoma in Slovakia. Description of a form of primary congenital glaucoma in gypsies with autosomal-recessive inheritance and complete penetrance. Dev Ophthalmol. 1989;16:76–115.

Gilbert CE, Canovas R, Kocksch de Canovas R, Foster A. Causes of blindness and severe visual impairment in children in Chile. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36(4):326–33.

Gilbert-Lucido ME et al. Estudio epidemiológico de glaucoma en población mexicana. Rev Mex Oftalmol. 2010; 84(2):86–90.

Glaucoma. Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 10. 2011–2012. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2011:139–58.

Grehn F, Mackensen G. Die Glaukome. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer ; 1993.

Jaafar, Mohamad S. "Care of the infantile glaucoma patient." Ophthalmology annual 7 (1988): 15-37.

Kanski JJ, Bowling B. Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. 7th ed. New York: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.

Mandal AK, Naduvilath TJ, Jayagandan A. Surgical results of combined trabeculotomy-trabeculectomy for developmental glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2007;105(6): 974–82.

Melka F, Alemu B. The pattern of glaucoma in Menelik II Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2006;44(2):159–65.

Moore DB, Tomkins O, Ben-Zion I. A review of primary congenital glaucoma in the developing world. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(3):278–85.

Morales J, Al Shahwan S, Al Odhayb S, Al Jadaan I, Edward DP. Current surgical options for the management of pediatric glaucoma. J Ophthalmol. 2013;2013:763735.

Mullaney PB, Selleck C, Al-Awad A, Al-Mesfer S, Zwaan J. Combined trabeculotomy and trabeculectomy as an initial procedure in uncomplicated congenital glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(4):457–60.

Papadopoulos M, Cable N, Rahi J, Khaw PT, BIG Eye Study Investigators. The British Infantile and Childhood Glaucoma (BIG) Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(9):4100–6.

Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 6. 2011–2012. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2011:233–44.

Qiao CY, Wang LH, Tang X, Wang T, Yang DY, Wang NL. Epidemiology of hospitalized pediatric glaucoma patients in Beijing Tongren Hospital. Chin Med J. 2009;122(10):1162–6.

Silva AM, Matos MH, Lima Hde C. [Low vision service at the Instituto Brasileiro de Oftalmologia e Prevenção da Cegueira (IBOPC): analysis of the patients examinedon the first year of the department (2004)]. Portuguese. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2010;73(3):266–70.

Sothornwit N, Jenchitr W, Pongprayoon C. Glaucoma care and clinical profile in Priest Hospital, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(Suppl 1):S111–8.

Yanoff M, Duker JS. Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby/Elsevier; 2008.