EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- In 2010, the worldwide estimated prevalence of angle-closure glaucoma was 15.7 million with nearly 25% of cases resulting in bilateral blindness.

- PACG is more commonly seen in women and certain ethnic groups.

- Higher in Inuits, East Asians, mixed ethnic groups in South Africa

- The rate of PACG among Inuits older than 40 years is 2.1%–5.0% of the population and 0.4%–1.3% among East Asians. In comparison, rates are exceedingly lower in Caucasians (0.1%–0.6%) and Africans (0.1%–0.2%).

- Most cases of PACG occur in the sixth to seventh decade of life. It is thought to be explained by age-related growth and forward movement of the crystalline lens. PACG is rare in patients younger than 40. (When observed in this age group, an etiology other than pupillary block should be suspected as detailed below.)

- See Table 1.

|

Table 1. Geographic Distribution of Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma

|

|

Latin America and the Caribbean

|

1.6%

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa

|

0.6%

|

|

Middle East/North Africa/South-west Asia

|

1.3%

|

|

China

|

37.1%

|

|

India

|

12.7%

|

|

Other Asian & Pacific countries (high income)

|

8.8%

|

|

Other Asian & Pacific countries (low income)

|

17.6%

|

|

Source: World Bank, 1994.

|

|

Regional Information (Asia)

|

Table 2. Geographic Prevalence of Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma

|

|

Country

|

Reported Prevalence (%)

|

|

Taiwan

|

3.0 (age ≥ 40)

|

|

Guangzhou (China)

|

1.5 (age ≥ 50)

|

|

Mongolia

|

1.4 (age ≥ 40)

|

|

Singapore

|

1.1 (age 40 – 79)

|

|

Southern India

|

0.5 - 1.08 (age ≥ 40)

|

|

Thailand

|

0.9 (age ≥ 50)

|

|

Bangladesh

|

0.4 (age ≥ 40)

|

|

Japan

|

0.34 – 0.6 (age ≥ 40)

|

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology Glaucoma Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Primary Angle Closure. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2010. Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Differential diagnosis of acute increase in intraocular pressure (IOP):

- Inflammatory open angle glaucoma

- Retrobulbar hemorrhage or inflammation

- Traumatic (hemolytic glaucoma)

- Glaucomatocyclitic crisis (Posner-Schlossman syndrome)

- Pigmentary glaucoma

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DEFINITION

Angle closure refers to a diverse group of anatomical disruptions of the anterior segment that lead to mechanical blockage of the trabecular meshwork by the peripheral iris, thereby resulting in increased IOP with subsequent optic disc and visual field changes that together diagnostically is referred to as angle-closure glaucoma.

Key Points

- Relative pupillary block is thought to account for >90% cases of primary angle closure (PAC) and primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) in East Asians.

- Plateau iris is an important cause of PAC and PACG in up to 30% of Chinese patients.

Etiology of Primary Angle Closure

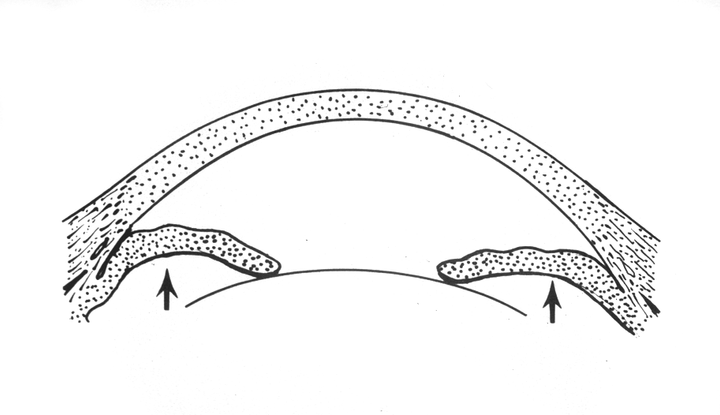

- Relative pupillary block (apposition of lens and posterior iris at pupil leads to blockage of aqueous humor from anterior to posterior chamber) (Figure 1)

- Angle crowding secondary to plateau iris or other abnormal iris configuration (Figure 2)

Etiology of Secondary Angle Closure

- Peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) secondary to inflammation including uveitis

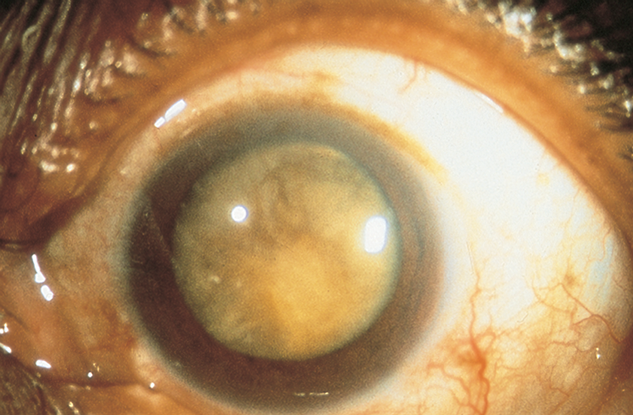

- Neovascular or fibrovascular membrane pulling angle closed (neovascular glaucoma, NVG) (Figure 3)

- Membrane obstructing angle in iridocorneal endothelial syndrome (ICE) or epithelial downgrowth

- Lens-induced

- Phacomorphic (iris-trabecular contact as a result of a large lens) (Figure 4)

- Nanophthalmos (small eye)

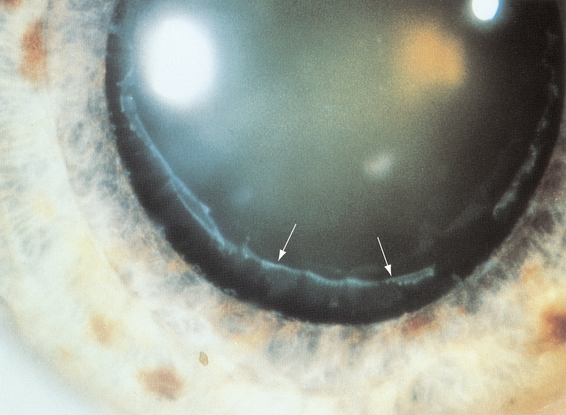

- Pseudoexfoliation syndrome (zonular loss/weakness) (Figure 5)

- Miotic-induced angle closure

- Drug sensitivity (topiramate and sulfonamides, also: antidepressants, anticholinergics, allergy and cold medications containing antihistamines) presenting with bilateral angle closure due to supraciliary effusion and ciliary body swelling, with consequent anterior rotation of lens–iris diaphragm

- Choroidal swelling following tight encircling scleral buckle, extensive retinal laser, retinal vein occlusion

- Posterior segment tumor

- Hemorrhage choroidal detachment

- Aqueous misdirection syndrome/malignant glaucoma

- Uveal effusion

- Posterior scleritis

- Retrolenticular tissue contracture (ROP/PHPV)

SIGNS, SYMPTOMS

Symptoms

- Pain (may radiate in CN V distribution with associated secondary lacrimation)

- Blurred vision

- Colored rings around lights

- Frontal headache

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Sweating

- Bradycardia

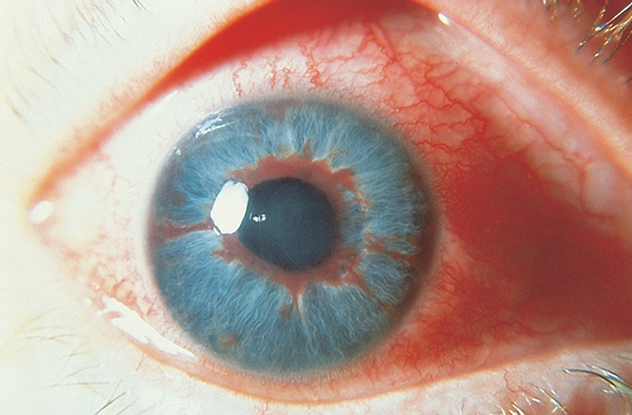

Signs

- Closed angle in involved eye

- Elevated IOP (sometimes as high as 70 mmHg)

- Cornea edema (microcystic)

- Conjunctival injection

- Fixed mid-dilated pupil

- Eyelid edema

Note:

- Examination of the fellow eye usually demonstrates shallow anterior chamber and narrow angle (useful in differentiating primary from secondary angle closure).

- Fundus examination may reveal optic disc edema and hyperemia in acute angle closure

Anterior Chamber Angle Assessment

- Van Herick technique: Peripheral temporal depth anterior chamber with slit-lamp beam < one-fourth depth of normal corneal thickness thought to be highly suspicious for angle closure.

- Not a substitute for gonioscopy

- Gonioscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis, indirect gonioscopy using a 4-mirror lens. Ideal conditions include:

- Completely dark room

- Thin slit-lamp beam

- No pressure on gonio lens initially

- Visualization of the entire angle 360° before any indentation

- During indentation, corneal curvature is altered thereby aqueous is sent peripherally into the angle recess opening an appositionally closes angle.

- Indentation gonioscopy useful in differentiating between appositional closure versus PAS, dynamic change observed under direct visualization

- Variety of angle grading systems, most common being the Shaffer and Spaeth systems

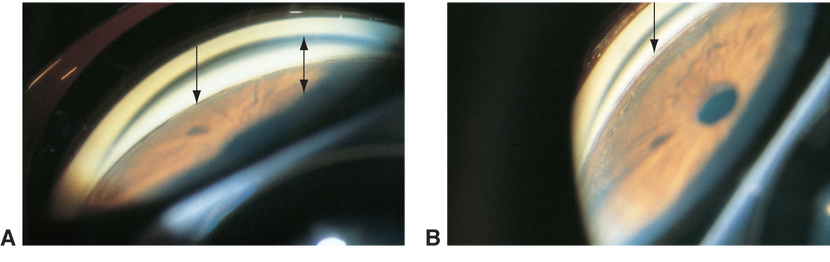

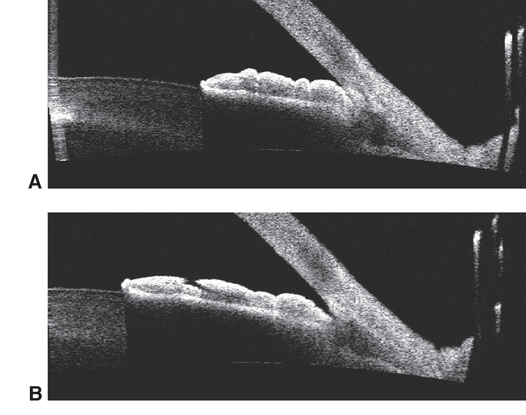

- If available, ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) is noninvasive and may assist in diagnosis and provide detailed information about the anterior chamber, ciliary body, zonules, iris configuration, lens, and posterior chamber (Figure 6).

- Newer technologies to further examine the angle include anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS- OCT), SPAC depth analyzer, Pentacam (www.meditec.zeiss.com).

MANAGEMENT

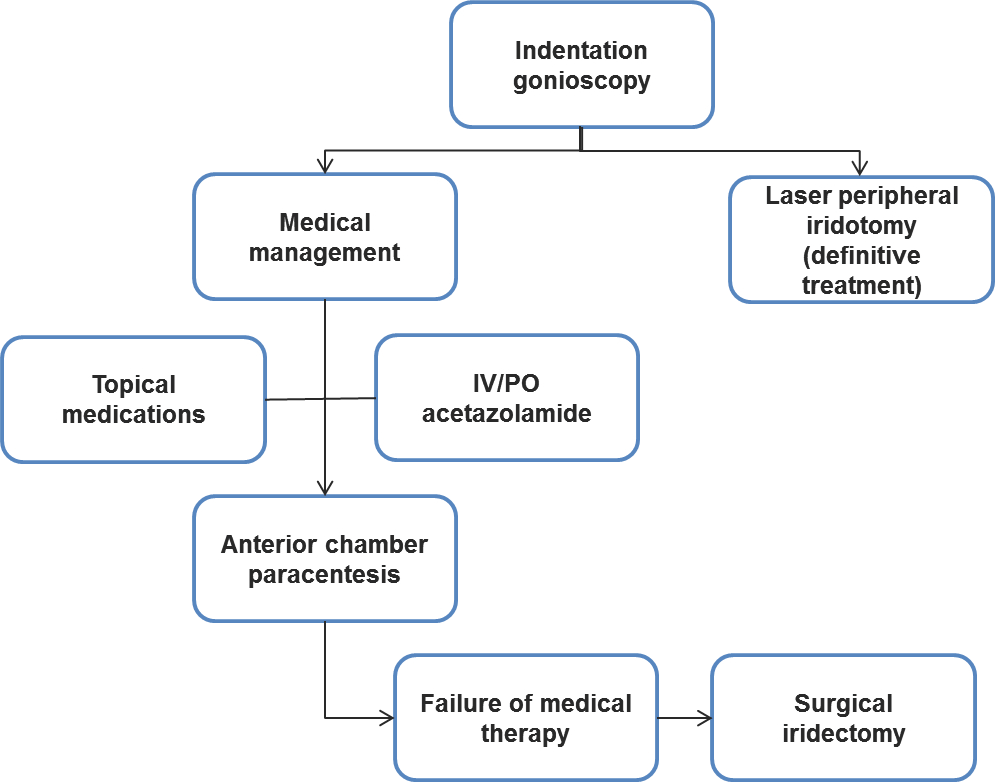

Chart 1. Management of primary angle-closure glaucoma

- Severe, permanent vision loss can occur within several hours.

- If visual acuity is severely reduced (worse than hands motion), urgent IOP-lowering therapy is needed.

Medical Management

- Indentation gonioscopy—may break an acute attack

- Topical aqueous suppressants

- Alpha 1-agonists (brimonidine 0.1%–0.2%)

- Topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (dorzolamide/brinzolamide)

- Topical beta-blocker (timolol 0.5%)—used with caution in asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Prostaglandin analogues (latanoprost/bimatoprost/travoprost)

- Steroids (prednisolone acetate 1%)

- Miotic agents (pilocarpine)—controversial

- Topical glycerin may be used to improve view through edematous cornea for examination or laser therapy

- Oral or intravenous carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (acetazolamide 250–500 mg) — caution with renal dysfunction

- Hyperosmotic agents (mannitol/glycerol)

- Anterior chamber paracentesis:

- May provide rapid lowering of IOP, pain and corneal edema

- Caution in phakic patients and large pupils

- Corneal indentation:

- Acute angle closure possibly relieved by forcefully pressing on the cornea with a 4-mirror indirect gonioscopy lens

- Laser iridotomy

- ND:YAG, argon diode, or combination of both

- Should be strongly considered in all patients

- Eliminated pressure differential between anterior and posterior chamber

- Contraindications: neovascular glaucoma, ICE syndrome, choroidal effusion

- Peripheral iridoplasty:

- Consider in cases where laser iridotomy not possible or does not eliminate appositional angle.

- Procedure places contracting burns in extreme iris periphery to contract iris stroma and physically pull open angle.

Surgery

- Indications similar to those for open angle glaucoma, principally when IOP cannot be managed with medical and/or laser therapy

- Trabeculectomy

- Glaucoma drainage tube implants

- Lens extraction with or without trabeculectomy

- Surgical iridectomy—patients uncooperative or nonsuitable for standard laser therapy

Note: There is increased risk of aqueous misdirection/malignant glaucoma following glaucoma surgery.

Management Plan

The following management plan is based on preferred practice at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, UK (Courtesy of Anthony Khawaja, MB, MA (Cantab), MRCOphth, University of Cambridge).

The basic principles of treatment of acute angle-closure are as follows:

- Treat acute attack.

- Break pupil block (pilocarpine, aqueous suppressants (by opening the angle) and indentation).

- Control IOP.

- Treat inflammation.

- Prevent future attacks with peripheral iridotomies.

- Detect and control ongoing glaucomatous optic neuropathy.

CASE STUDY

History of Present Illness

A 56-year-old woman presents with no prior medical history. She had gone with her family to see a matinee movie in the early afternoon and noticed that her right eye began to ache when leaving the theater. The pain increased through the afternoon and the eye became progressively more red. Upon presentation the next day, she had a severe right-sided headache, photosensitivity, nausea, an episode of emesis, epiphora, and blurry vision of the right eye.

Examination

- Visual acuity: 20/80 vision in the right eye, 20/15 vision in the left eye with a refractive error of +2.75 in both eyes.

- Pupil examination: Her right pupil was fixed and mid-dilated at 6 mm and did not change in light or dark. Her left pupil was round and reactive, and there was no afferent pupillary defect by reverse.

- Intraocular pressure: 65 mmHg in the right eye and 25 mmHg in the left eye

- Slit lamp examination: Conjunctiva was injected OD. Cornea was edematous and hazy OD. Anterior chamber was narrow and there was cell and flare present OD. Iris, pupil was fixed and mid dilated OD.

- Fundus examination (non-dilated): optic nerve, macula, and vessels were unremarkable.

- Gonioscopy: Closed angle in the right eye and a narrow angle in the left eye with no neovascularization.

Treatment

Initial therapy:

- Diamox 500mg po x1

- Three rounds of one drop of alpha 1-agonist (brimonidine 0.1%–0.2%),

- A topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (dorzolamide/brinzolamide),

- A topical beta-blocker (timolol 0.5%),

- A topical prostaglandin analogue (latanoprost/bimatoprost/travoprost) and

- A topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1%) in the right eye only.

All drops were separated by 5 minutes and serial intraocular pressure measurements were made. Her intraocular pressure was decreased to 22 mmHg. She was sent home on Diamox 500 mg po daily and topical brimonidine, timolol, and bimatoprost.

The following day her intraocular pressure was 21 mmHg. She was maintained on the topical regimen and Diamox was discontinued. She returned to the clinic a week later with 20/15 visual acuity in both eyes and intraocular pressures of 22 mmHg in both eyes. Peripheral laser iridotomy was performed in the right eye. She returned one week later and had peripheral laser iridotomy of the left eye.

IMAGE LIBRARY

Pathophysiology/Definition

Figure 1. Sketch of pupillary block. A relative seal between iris and lens traps aqueous in the posterior chamber. The aqueous pushes the peripheral iris forward, causing iris bombe and eventual angle closure. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 2. Angle crowding secondary to plateau iris or other abnormal iris configuration © 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of M. Roy Wilson, MD.)

Figure 3. Neovascular or fibrovascular membrane pulling angle closed. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of Steven T. Simmons, MD.)

Figure 4. Phacomorphic secondary angle closure (iris-trabecular contact as a result of a large lens). (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of Steven T. Simmons, MD.)

Figure 5. Pseudoexfoliation syndrome (zonular loss/weakness). (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Signs, Symptoms

Figure 6. Anterior chamber angle assessment. Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) is noninvasive and may assist in diagnosis and provide detailed information about the anterior chamber, ciliary body, zonules, iris configuration, lens, and posterior chamber. (Reproduced, with permission, from Cioffi GA. Glaucoma. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 10, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Courtesy of Yaniv Barkana, MD.)

REFERENCES

American Academy of Ophthalmology Glaucoma Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern®Guidelines. Primary Angle Closure. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2010. Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

Friedberg M, Rapuano C. Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 5th ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2008.

Glaucoma. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section10, 2011–2012. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2011.

Tsai JC, Tello C, Ritch R. Angle-closure glaucoma update. Focal Points: Clinical Modules for Ophthalmologists. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2009, Module 6.

Sakata K, Sakata LM, Sakata VM, et al. Prevalence of glaucoma in South Brazilian population: projeto glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;11:4974–4979.

Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Francis BA, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1439–1448.

Quigley HA, West SK, Rodriguez J, Munoz B, Klein R, Snyder R. The prevalence of glaucoma in a population-based study of Hispanic subjects: Proyecto VER. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1819–1826.

Packzka JA. Epidemiología del Glaucoma en América Latina. Vision 2020 Latinoamérica Boletín Trimestral. Vision2020la.wordpress.com/2013/03/26/1521/. Accessed October 2, 2013.

CONTRIBUTORS

Sandra Belalcazar-Rey. Glaucoma Department at Fundación Oftalmológica Nacional. Bogotá, Colombia

Kristin Chapman, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York, New York

Executive Editor: R. V. Paul Chan, MD, FACS, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Section Editors:

Timothy Y. Lai, MBBS, MD, MMedSc, FRCS, FRCOphth, FHKAM, Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Manish Nagpal, MBBS, MS, FRCS, Retina Foundation & Eye Research Center, Ahmedabad, India

Assistant Editors:

Swetangi D. Bhaleeya, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Kristin Chapman, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Peter Coombs, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Michael Klufas, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Samir Patel, medical student, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Region Contributor:

Kristin Chapman, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Copyright © 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology®. All Rights Reserved.