EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- The prevalence of pterygium was found to be 10.2% in the world, with highest prevalence in low altitude regions (Liu et al, 2013).

- Increased incidence of pterygium is noted in the tropics and in an equatorial zone between 30° north and south latitudes (Liu et al, 2013).

- Higher incidence is associated with chronic sun exposure (ultraviolet light), older age, male sex, and outdoor activity (Liu et al, 2013).

Regional Information (EUROPE)

- A study in Western Spain found the prevalence of pterygium to be 5.9% among the general population (Viso et al, 2011).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY / DEFINITION

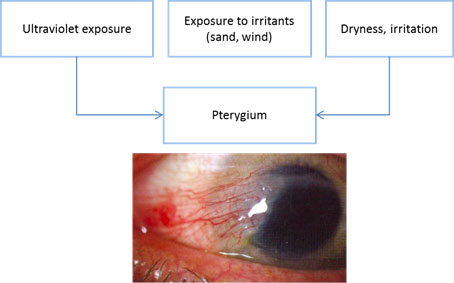

Chart 1. Pterygium pathophysiology. See Image Library for figure.

- Pterygium comes from the Greek word meaning wing, pterygos.

- Pterygium is a triangular fibrovascular growth that extends from the conjunctiva toward the cornea.

- It is more common in the interpalpebral fissure area and may occur nasally or temporally or both. The nasal location is more common.

- Although the pathophysiology is not clearly understood, ultraviolet (UV) light is identified as the most important risk factor.

- UV light forms free radicals that induce damage in DNA, RNA, and the extracelluar matrix of cells.

- Ultraviolet-B (UVB) induces expression of cytokines and growth factors in pterygial epithelial cells.

- Polymorphisms of the DNA break repair gene Ku70 have been associated with genetic predisposition to pterygia development.

- Increased levels of T-cells and inflammatory markers have also been noted in pterygial tissue compared to normal conjunctival tissue.

Risk Factors

- Ultraviolet exposure (single most significant risk factor)

- Exposure to irritants (dust, sand, wind)

- Inflammation

- Dry ocular surface

SIGNS/SYMPTOMS

Signs

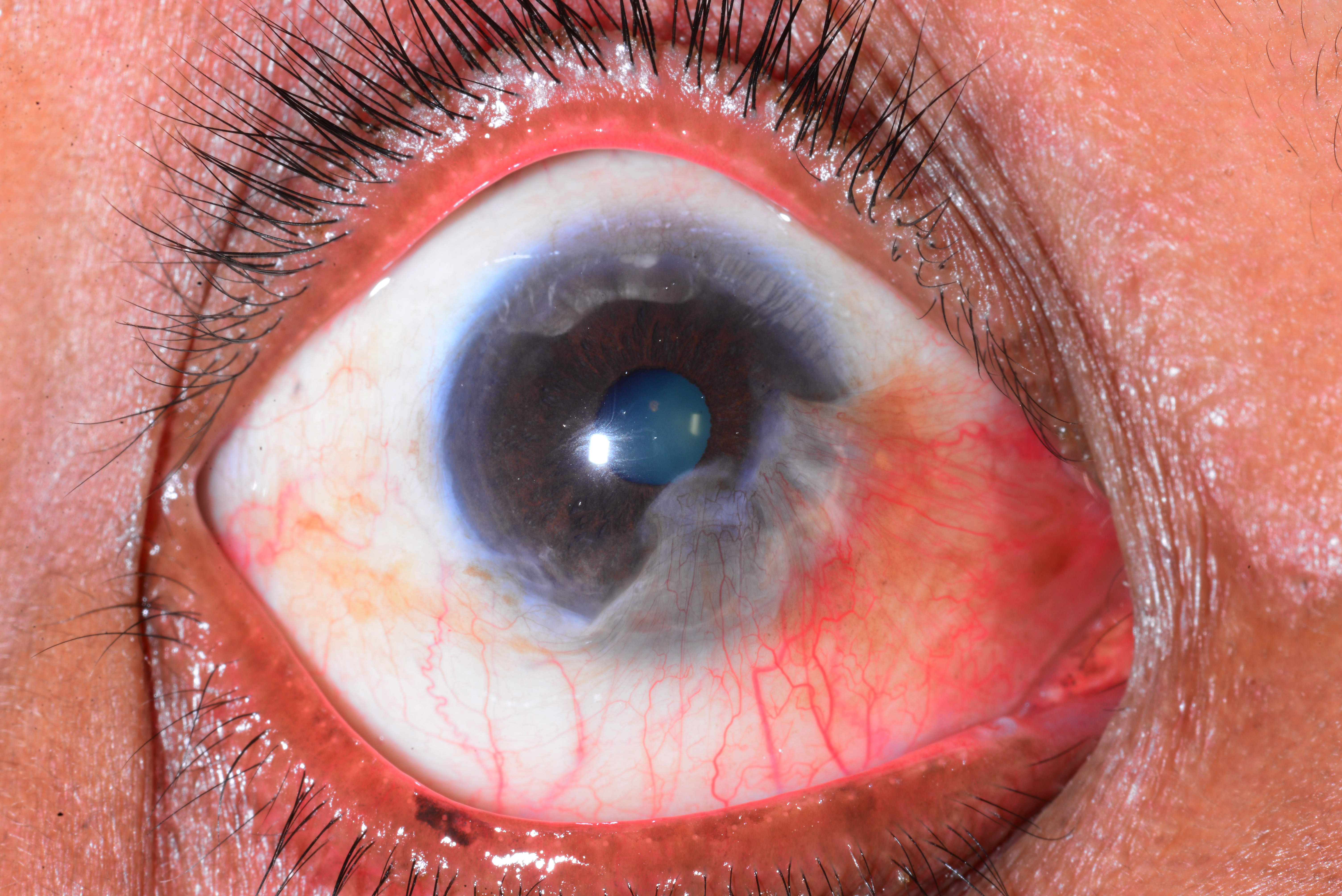

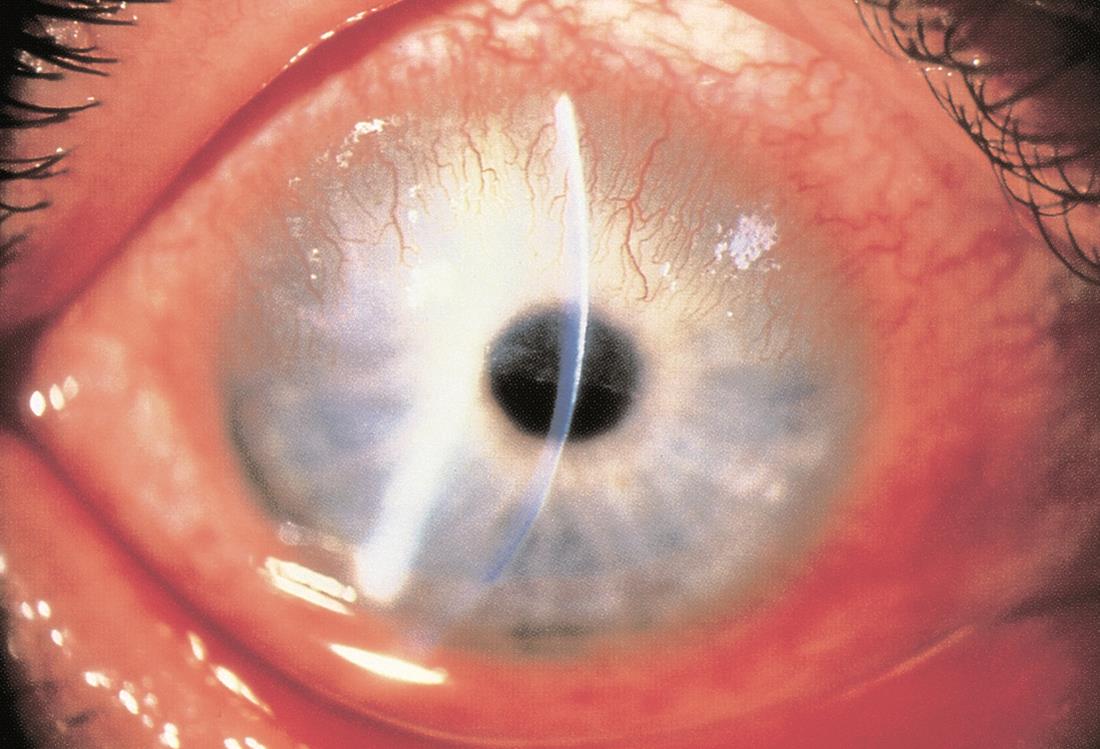

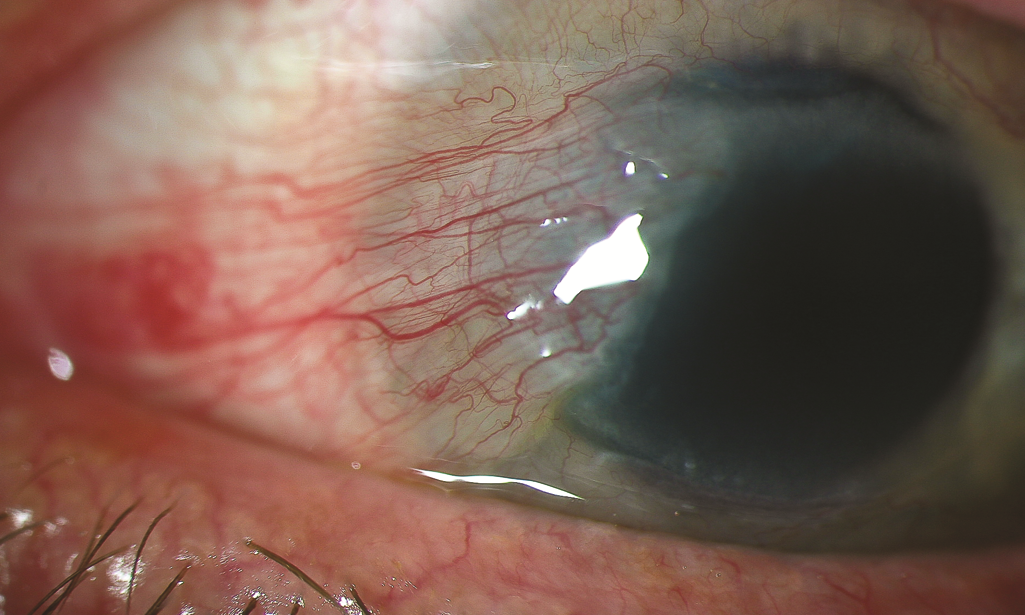

- Wedge-shaped, translucent membrane with apex extending onto cornea (Figure 6)

- White to pink in color, depending on vascularity

- Vascular straightening in the direction of the advancing head of the pterygium

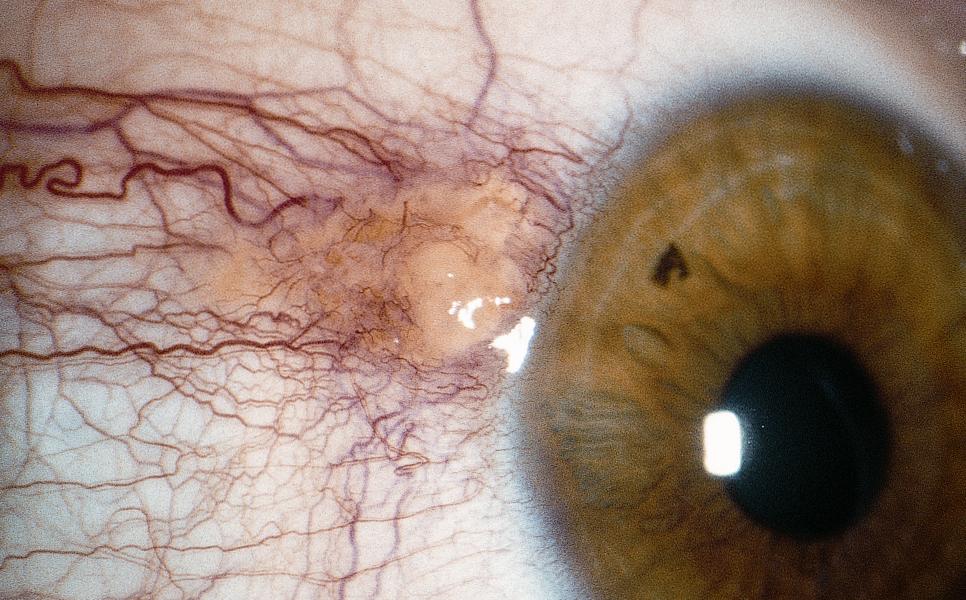

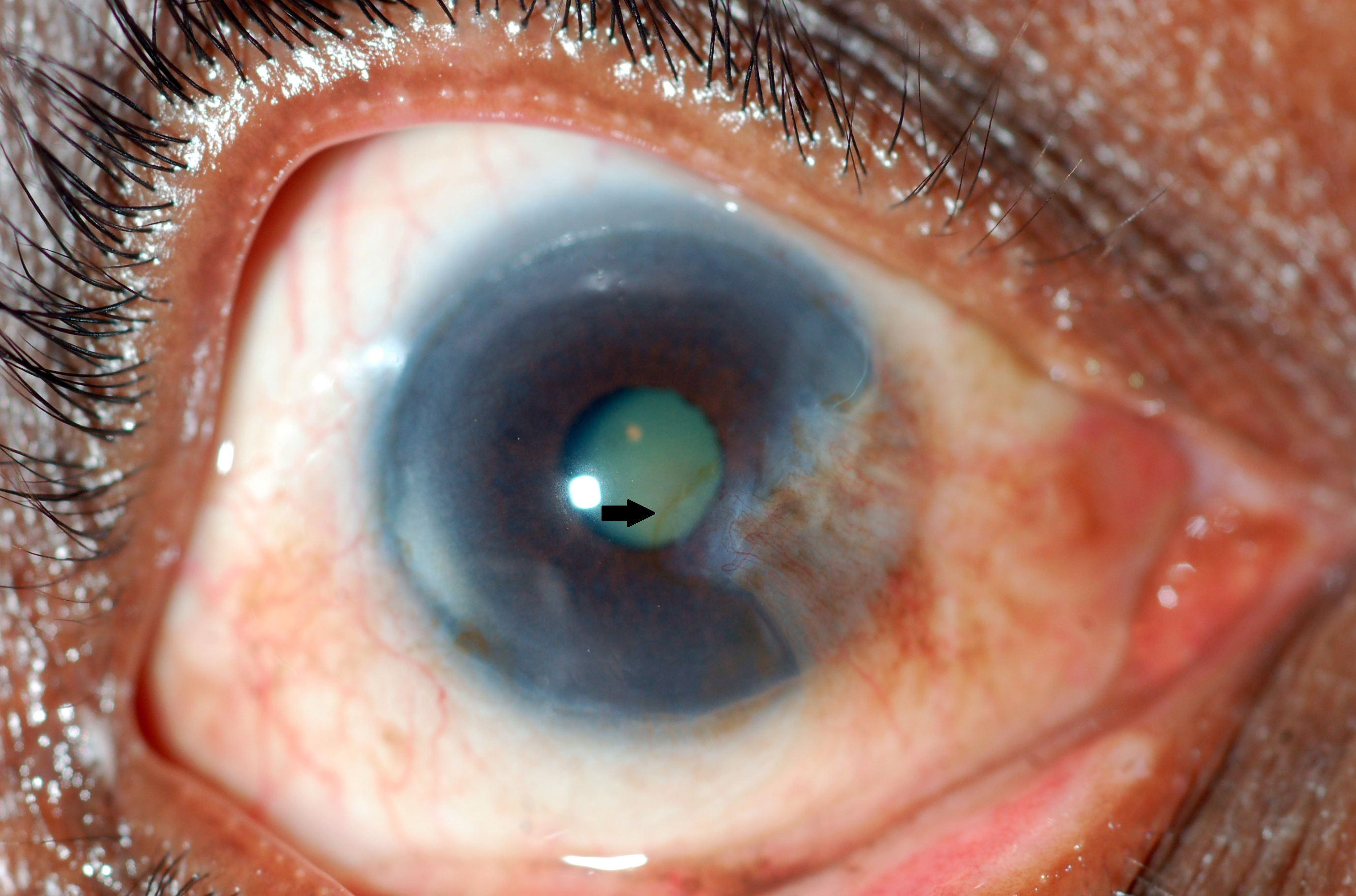

- Stocker line: iron line on cornea at leading edge of pterygium (Figure 7)

- Regular or irregular astigmatism

- Degenerative changes such as cystic changes

Symptoms

- May be asymptomatic

- Redness

- Irritation

- Decreased vision

Diagnosis

- Diagnosis is made clinically based on slit-lamp examination and typical appearance of the lesion (Figure 1).

MANAGEMENT

Prevention

- Wearing eye protection, sunglasses, goggles, and/or a brimmed hat is recommended when one is exposed to sunlight or dust.

- Sunglasses that block 99%–100% of both UVA and UVB rays are preferred.

Medical Management

- Small pterygia without visual impairment can be treated symptomatically with artificial tears and ocular lubricants.

- Medical treatment (artificial tears and lubricants) does not decrease progression or cause regression of pterygia.

- In patients with irritative symptoms, preservative-free artificial tears are recommended for mild inflammation and topical steroids are recommended for moderate inflammation.

- Monitoring pterygia at 6–12 months is reasonable.

Surgical Management

Surgical removal is considered for the following conditions:

- Decrease in visual acuity due to astigmatism or encroachment onto visual axis

- A cosmetically significant pterygium

- When it interferes with contact lens wear

- Symptomatic degenerative changes like cystic changes

- Restriction of extraocular movements

Surgical techniques include the following:

- Simple excision (without transplantation, aka bare sclera) is associated with a higher recurrence rate and hence it has been supplemented with conjunctival transplantation.

- Adjuvant therapies including mitomycin C (MMC), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), ethanol, irradiation, and anti-angiogenic agents, among others, are used to reduce recurrence rate, but there is insufficient evidence that one is superior (Kaufman et al, 2013).

- The ideal treatment recommended involves excision of pterygium with conjunctival autograft (CAG) supplementation. Alternatively, if there is not enough conjunctiva, then amniotic membrane transplant (AMT) may be glued or sutured into place (Figure 8).

- Procedures using fibrin glue take about half the time as surgeries using sutures and patients often report less postoperative surgical pain and discomfort (Marticorena, Joaquin et al, 2006).

- However, fibrin glue is more expensive and can be difficult to obtain in some countries.

- The glue is a blood-derived product and carries the risk (however minimal) of viral and prion disease.

- Another approach is autoblood graft fixation, a technique also known as suture- and glue-free autologous graft. This approach affixes the graft into place with the patient’s own blood, eliminating the concern of disease transmission.

Postoperative Management

- Patch/shield overnight

- Drops: Steroid antibiotic combination 4 times a day for 1 month

Complications of Pterygium Surgery

Intraoperative:

- Buttonhole of the conjunctival autograft

- Injury to extraocular muscles

Postoperative (immediate):

- Graft slippage

- Graft retraction

- Donor site granuloma formation

Long-term complications:

- The most common complication is recurrence after removal.

- The recurrence rate is as high as 50% within 4 months and 97% recurrence rate within 12 months without autograft or amniotic membrane transplant (Hirst LW, 2003).

- The recurrence rate is higher with fleshy, nontranslucent pterygia and increased postoperative inflammation. It is often dependent on the surgical procedure.

- The recurrence rate is decreased to 5%–10% with conjunctival flap/graft supplementation.

- Other complications include corneal scarring, corneal perforation, strabismus, nonhealing defect (especially with mitomycin C), scleral melt (especially with mitomycin C), and scleral dellen (Figure 9) (Kaufman, SC et al, 2013).

- If scleral dellen are present, aggressive lubrication with artificial tear ointment every 2 hours.

- Scleral graft patch is placed in severe cases of scleral thinning. (Tsai et al, 2002)

CASE STUDY

History of Present Illness

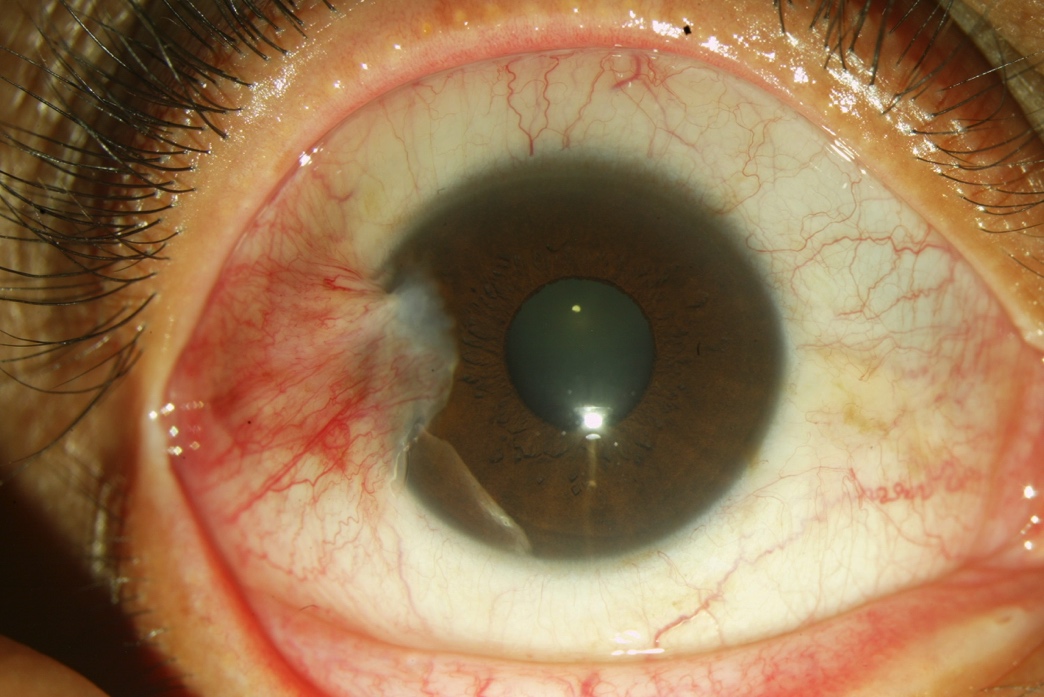

A 45-year-old patient presented with hyperemia, foreign body sensation, and itchiness in her right eye without improvement after artificial tears. Her family history is significant for diabetes. Eyelids of the right eye were within normal limits. The right eye had mild conjunctival hyperemia and a 2–3 mm temporal pterygium without involvement of the papillary area (Figure 10). Ocular examination of the left eye was normal.

Treatment

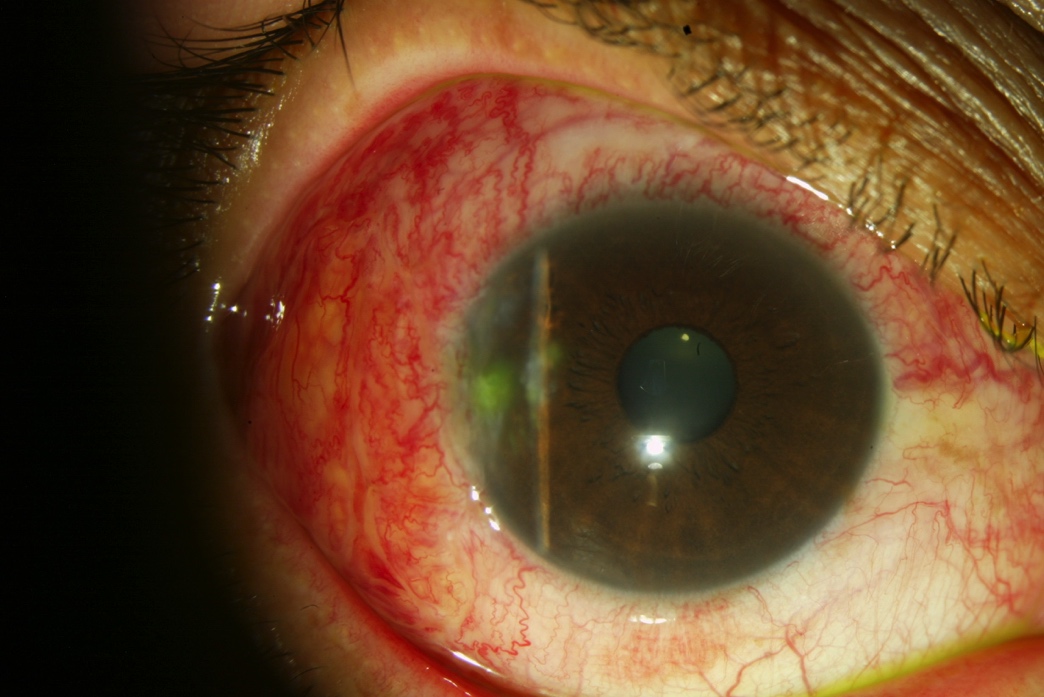

Resection of pterygium plus conjunctival autograft in right eye. One week after surgery, there is mild conjunctival hyperemia and chemosis with complete resection of the pterygium (Figure 11).

IMAGE LIBRARY

Differential Diagnosis

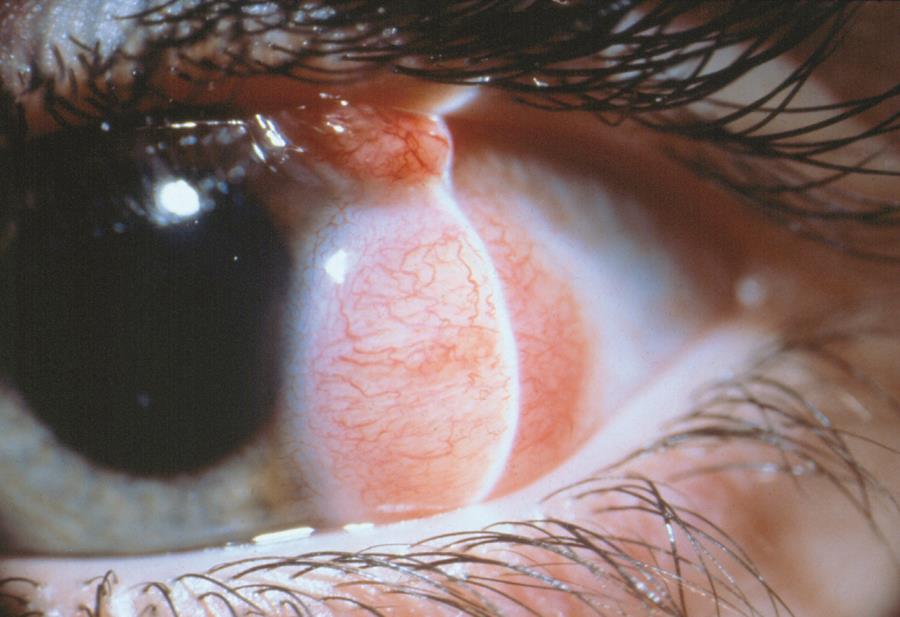

Figure 1. Pseudopterygium. (Courtesy Dr. N. Nenkatesh Prajna.)

Figure 2. Pinguecula. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 3. Pannus. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

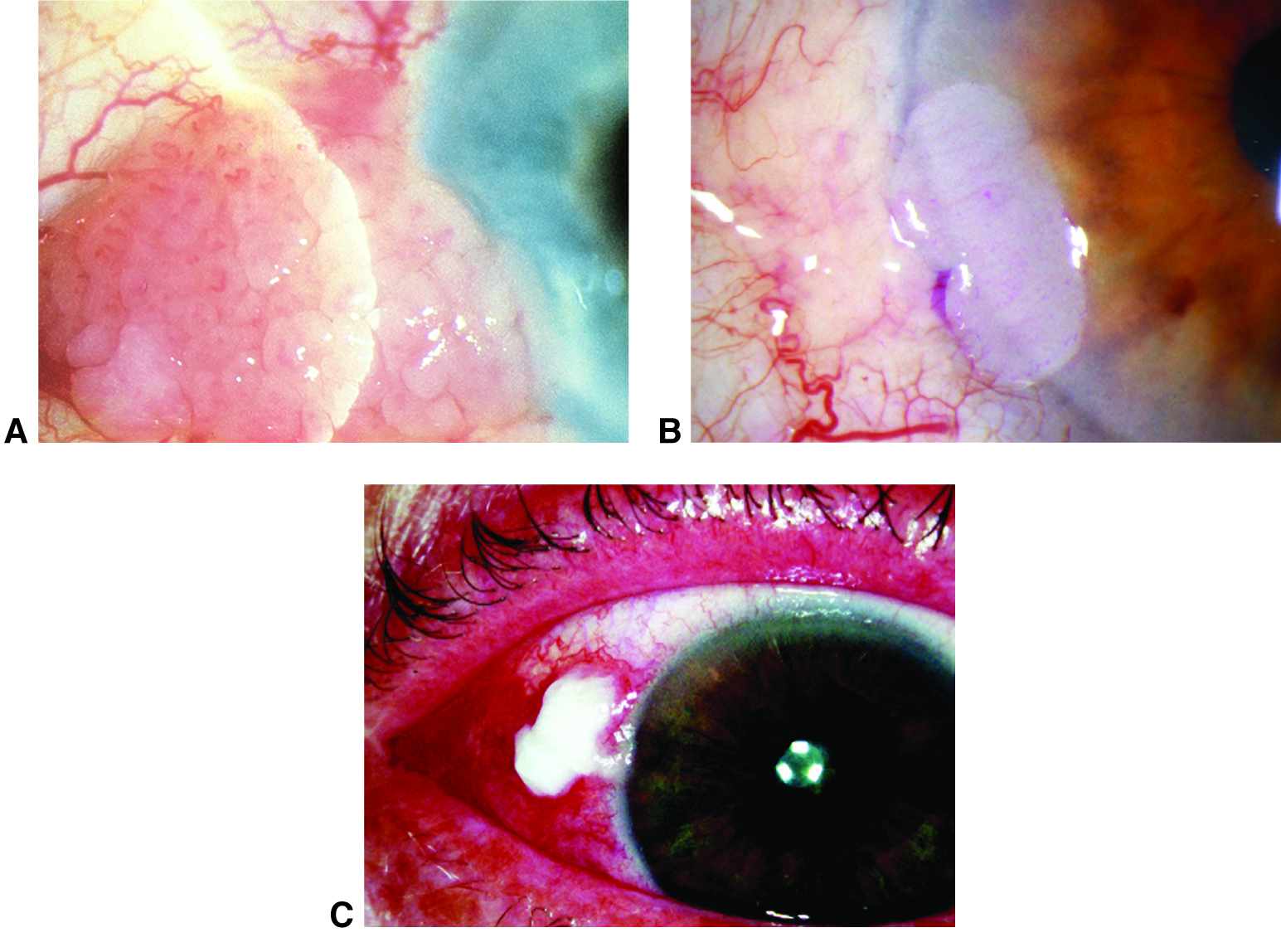

Figure 4. Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. A. Papilliform. B. Gelatinous. C. Leukoplakic. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 5. Limbal dermoid. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Signs/Symptoms

Figure 6. Slit-lamp image of a pterygium. (Reproduced, with permission, from Reidy, JJ, Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 8: External Disease and Cornea. American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2010–2011).

Figure 7. Stocker line (arrow). (Courtesy Dr. N. Nenkatesh Prajna.)

Management

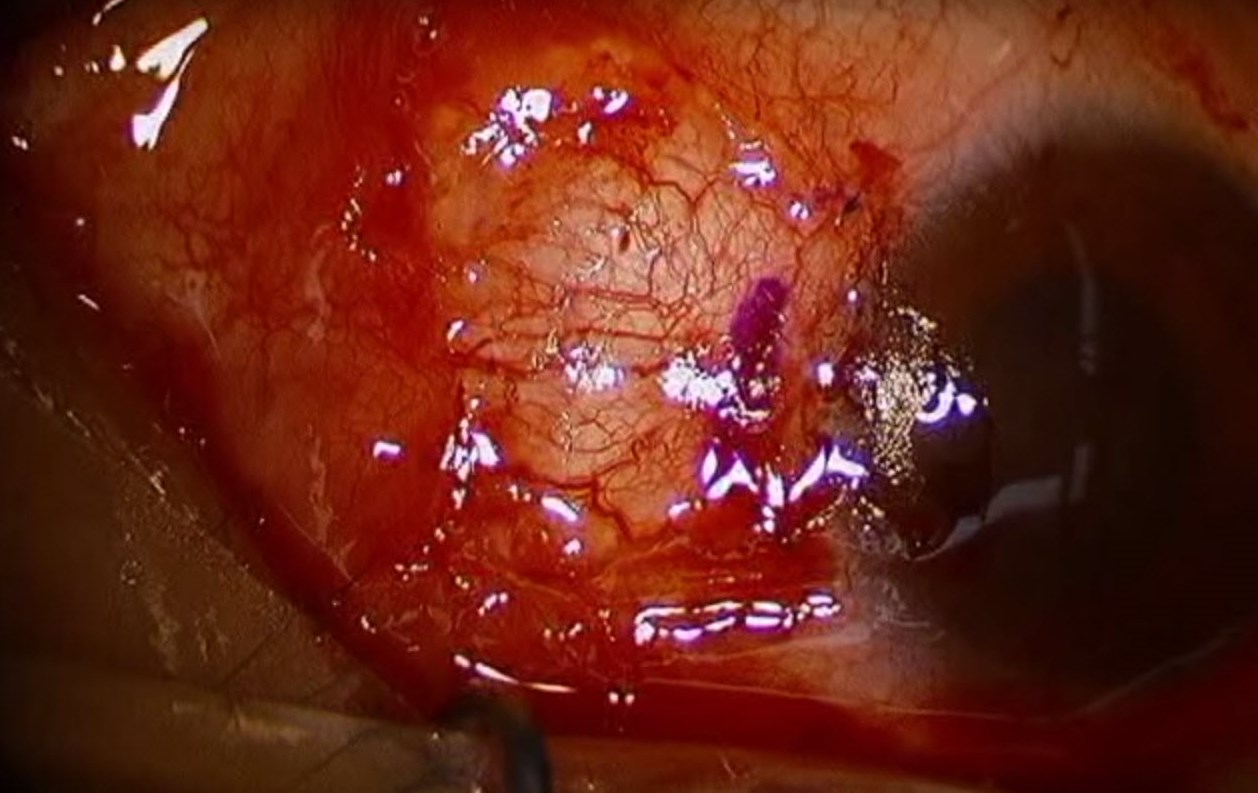

Figure 8. Immediate postoperative photograph showing a suture conjunctival autograft after pterygium excision. (Reproduced from Ward M. Pterygium excision with conjunctival autograft. EyeRounds Online Atlas of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 9. Scleral dellen. (Reproduced from Garcia-Medina JJ et al. Severe scleral dellen as an early complication of pterygium excision with simple conjunctival closure and review of the literature. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2014;77[3].)

Case Study

Figure 10. A 2–3 mm temporal pterygium without involvement of the papillary.

Figure 11. One week after resection of the pterygium and placement of temporal conjunctival autograft.

REFERENCES

Ajayi Iyiade A, Omotoye Olusola J. Pattern of eye diseases among welders in a Nigeria community. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12(2):210–26.

Alqahtani JM. The prevalence of pterygium in Alkhobar: A hospital-based study. J Family Community Med. 2013;20(3):159–61.

Bueno-Gimeno I, Montés-Micó R, España-Gregori E, et al. Epidemiologic study of pterygium in a Saharan population. Ann Ophthalmol. 2002;34(1):43–6.

Cajucom-Uy H, Tong L, Wong TY, et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for pterygium in an urban Malay population: the Singapore Malay Eye Study (SiMES). Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(8):977–81.

Chan TC, Wong RL, Li EY, et al. Twelve-year outcomes of pterygium excision with conjunctival autograft versus intraoperative mitomycin c in double-head pterygium surgery. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:891582.

Durkin SR, Abhary S, Newland HS, et al. The prevalence, severity and risk factors for pterygium in central Myanmar: the Meiktila Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(1):25–9.

External Disease and Cornea. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 8, 2015–2016. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2015.

Eze BI, Maduka-okafor FC, Okoye OI, Chuka-okosa CM. Pterygium: a review of clinical features and surgical treatment. Niger J Med. 2011;20(1):7–14.

Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K. Prevalence and risk factors of pterygium and pinguecula: the Tehran Eye Study. Eye (Lond). 2009;23(5):1125–9.

Friedberg M, Rapuano C. Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 5th ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

Gazzard G, Saw SM, Farook M, et al. Pterygium in Indonesia: prevalence, severity and risk factors.Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(12):1341–6.

Hirst, Lawrence W. The treatment of pterygium. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(2):145–80.

Kaufman S C, Jacobs D S, Lee WB, Deng SX, Rosenblatt MI, Shtein RM. Options and adjuvants in surgery for pterygium: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(1):201–8.

Kumah DB, Oteng-Amoako AO, Apio H. Prevalence of pterygium among kitchen staff in senior high schools in the Kumasi metropolis, Ghana. Ghana Journal of Science. 2011;13(2): 83–88.

Liu L, Wu J, Geng J, Yuan Z, Huang D. Geographical prevalence and risk factors for pterygium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):e003787.

Lu P, Chen X, Kang Y, Ke L, Wei X, Zhang W. Pterygium in Tibetans: a population-based study in China. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35(9):828–33.

Ma K, Xu L, Jie Y, Jonas JB. Prevalence of and factors associated with pterygium in adult Chinese: the Beijing Eye Study. Cornea. 2007;26(1)\0):1184–6.

Marcovich AL, Bahar I, Srinivasan S, Slomovic AR. Surgical management of pterygium. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50(3):47–61.

Marticorena, Joaquín, et al. "Pterygium surgery: conjunctival autograft using a fibrin adhesive." Cornea 25.1 (2006): 34-36.

McCarty CA, Fu CL, Taylor HR. Epidemiology of pterygium in Victoria, Australia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84(3):289–92.

Meseret A, Bejiga A, Ayalew M. Prevalence of pterygium in rural community of Meskan District, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2009;22(2):191–4.

Rojas JR, Málaga H. Pterygium in Lima, Peru. Ann Ophthalmol. 1986;18(4):147–9.

Sarac O, Toklu Y, Sahin M. The prevalence of pterygium in Ankara: a hospital-based study. Turk J Med Sci. 2012;42(6):1006–9.

Shiratori CA, Barros JC, Lourenço Rde M, Padovani CR, Cordeiro R, Schellini SA. Prevalence of pterygium in Botucatu city - São Paulo State, Brazil. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2010;73(4):343–5.

Shiroma H, Higa A, Sawaguchi S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of pterygium in a southwestern island of Japan: the Kumejima Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(5):766–771.e1.

Srinivasan S,Dollin M,McAllum P, Berger Y, Rootman DS, Slomovic AR. Fibrin glue versus sutures for attaching the conjunctival autograft in pterygium surgery : a prospective observer masked clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(2):215–8,

Todani A, Melki SA. Pterygium: current concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2009;49(1):21–30.

Tsai YY, Lin JM, Shy JD. Acute scleral thinning after pterygium excision with intraoperative mitomycin C: a case report of scleral dellen after bare sclera technique and review of the literature. Cornea. 2002;21(2):227–9.

Viso E, Gude F, Rodríguez-Ares MT. Prevalence of pinguecula and pterygium in a general population in Spain. Eye (Lond). 2011;25(3):350–7.

West S, Muñoz B. Prevalence of pterygium in Latinos: Proyecto VER. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(10):1287–90.

Wu K, He M, Xu J, Li S. Pterygium in aged population in Doumen County, China. Yan Ke Xue Bao.2002;18(3):181–4.