EPIDEMIOLOGY

General Information

- Worldwide, there are 8000–9000 new cases (1:15000–20000 live births) of retinoblastoma annually.

- Racial predilections and incidence of retinoblastoma are relatively uniform across populations.

- More than 95% of retinoblastoma cases occur before the age of 8 years.

- Retinoblastoma is almost always fatal without treatment.

- Delays in diagnosis and time to presentation have increased morality globally in less-developed countries.

- Occurrence of metastases is higher in low-income countries (32% vs 12% in middle-income countries). See Table 1 for survival data based on income.

|

Table 1. Survival from Retinoblastoma Based on Income

|

|

High-income countries

|

>90%

|

|

Middle-income countries

|

70%–79%

|

|

Low-income countries

|

40%

|

Regional Information (Europe)

- See Table 2 for broader incidence data.

|

Table 2. Incidence of Retinoblastoma in Children (Age 0–14 years) in Europe From 1988–1997

|

|

Region

|

Number

|

Age-Standardized Incidence Rate per Million

|

|

British Isles

|

369

|

4.4

|

|

East

|

152

|

3.4

|

|

North

|

128

|

5.2

|

|

South

|

117

|

3.9

|

|

West

|

627

|

3.9

|

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

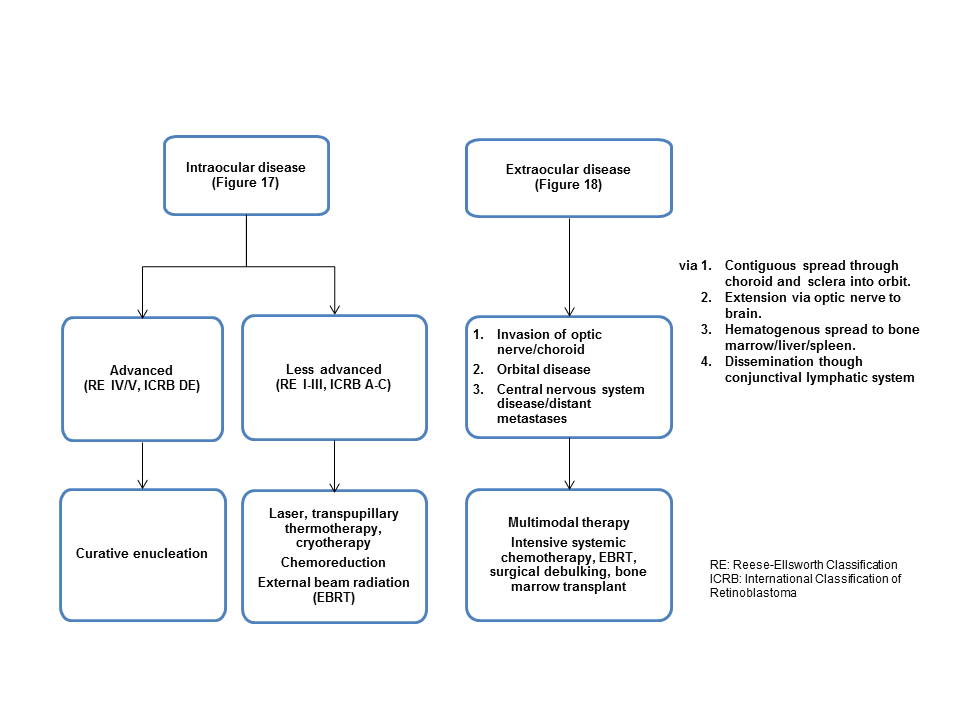

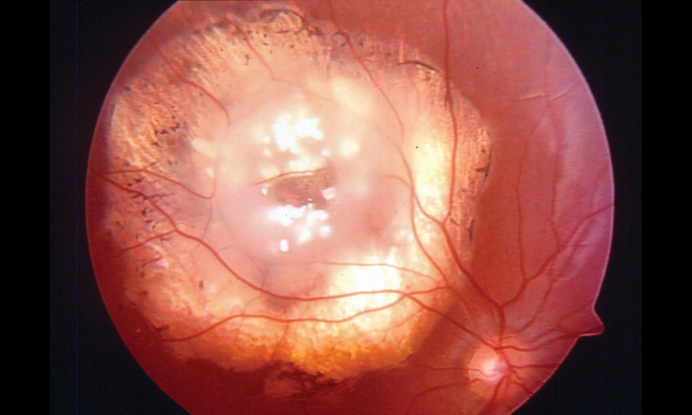

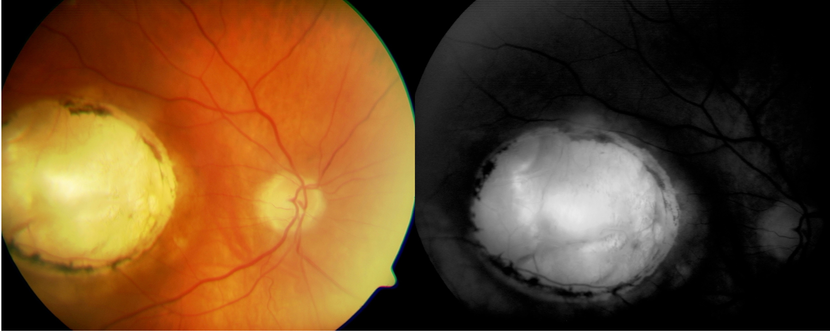

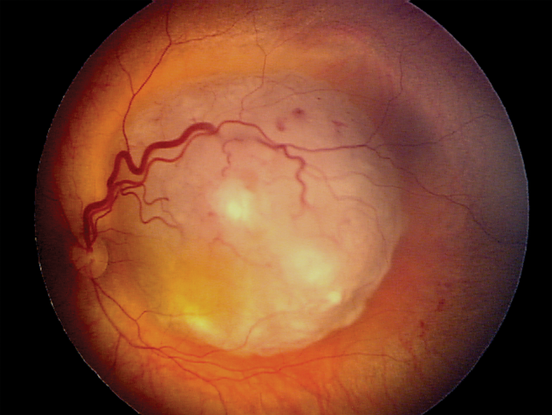

- Coats disease (Figure 1)

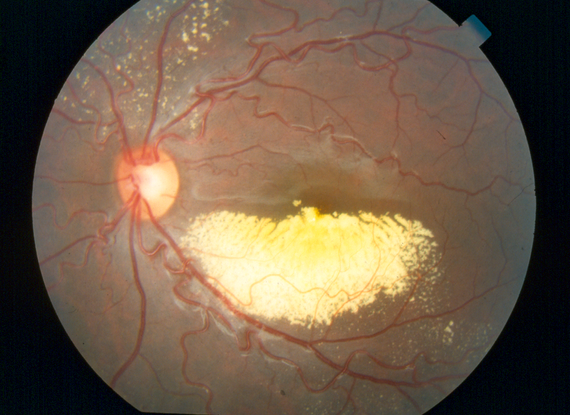

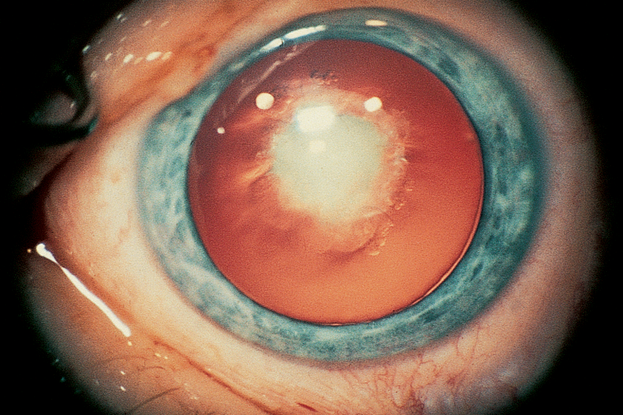

- Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV)/persistent fetal vasculature (PFV) (Figure 2)

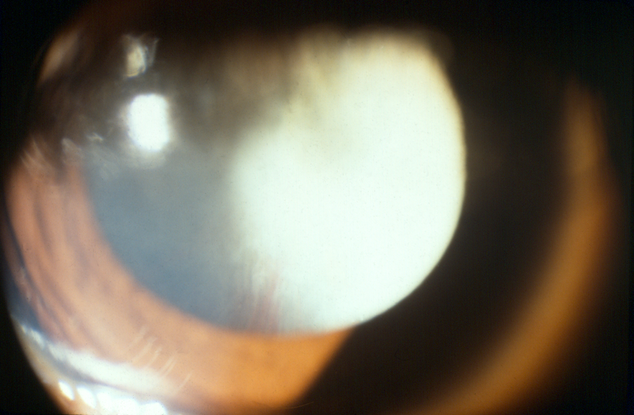

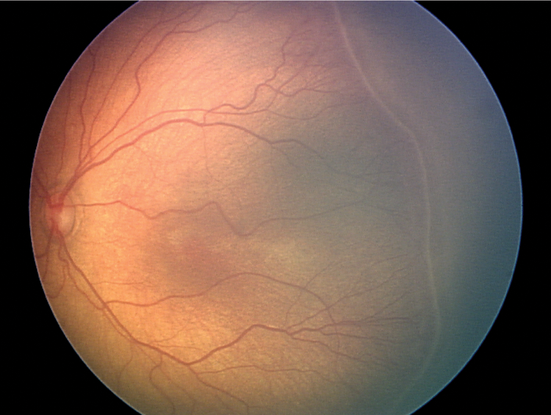

- Ocular toxocariasis (Figure 3)

- Retinocytoma (Figure 4)

- Retinal astrocytoma

- Medulloepithelioma/diktyoma

- Congenital cataract (Figure 5)

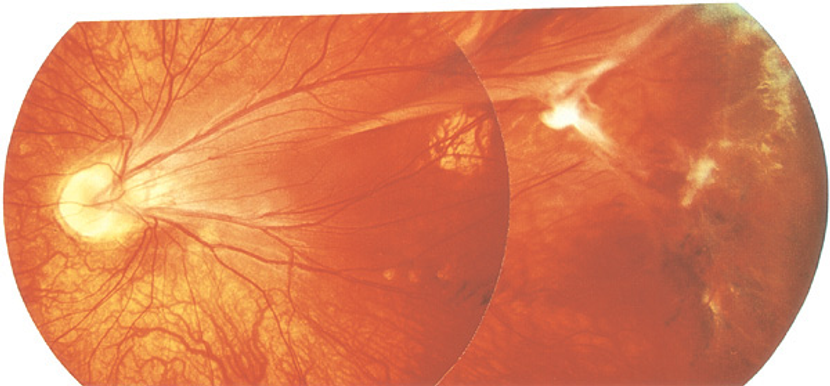

- Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) (Figure 6)

- Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) (Figure 7)

- Norrie disease

- Incontinentia pigmenti

- Choroidal coloboma (Figure 8)

- Uveitis

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY / DEFINITION

Genetics

- The disease is caused by a mutation in the RB1 gene located on the long arm of chromosome 13 (13q14).

- RB1 is a tumor suppressor gene and both copies of the gene must be affected for the tumor to form.

- The lack of a functioning RB1 tumor suppressor gene in a cell leads to retinoblastoma tumor formation,

- Retinoblastoma can be caused by germline or non-germline mutations. Table 3 shows characteristics of both types.

- 95% of cases are sporadic; 5% have a family history of retinoblastoma.

- With a positive family history and germline mutation, the penetrance is approximately 90%.

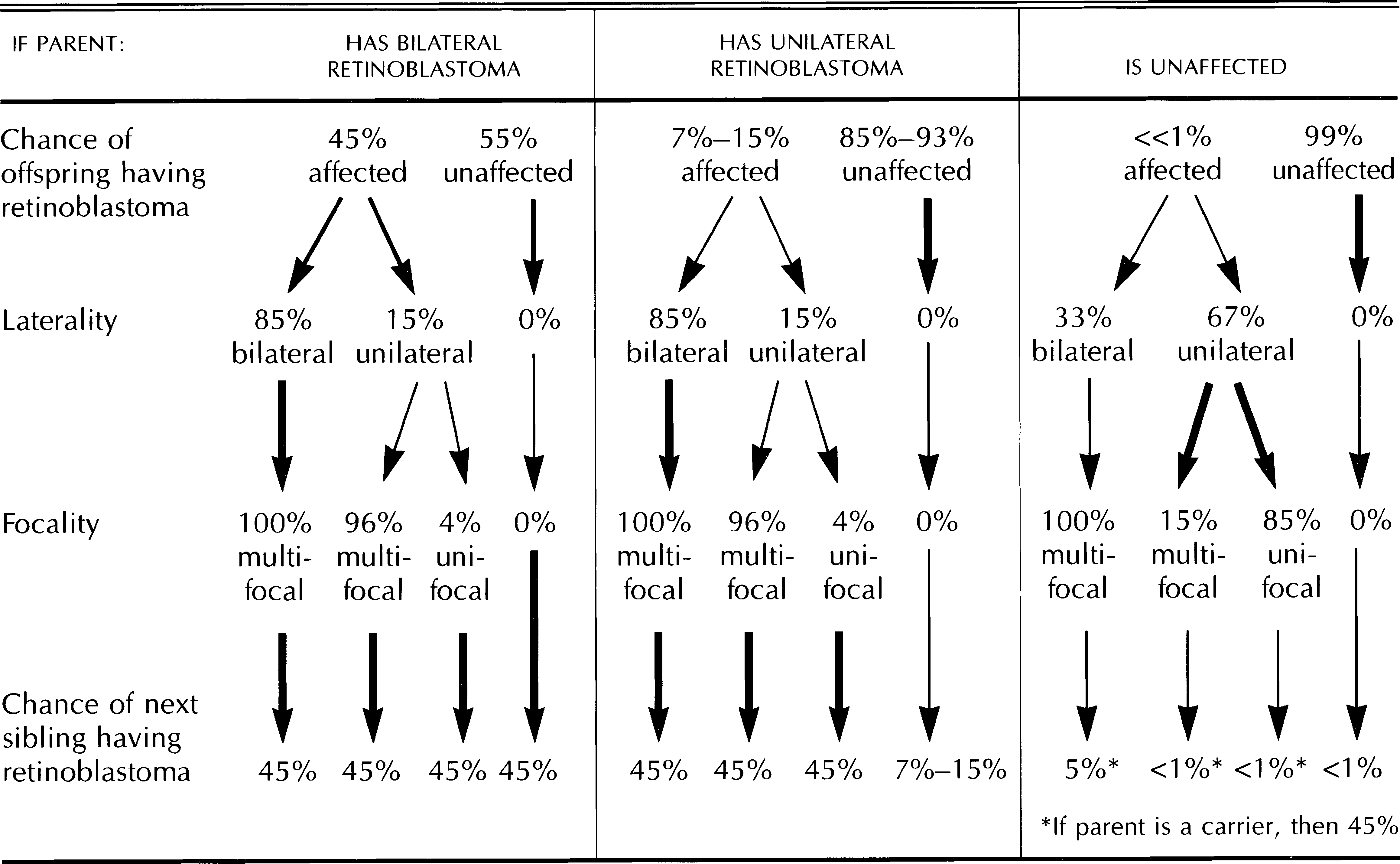

Figure 9 characterizes the genetics of retinoblastoma.

|

Table 3. Characteristics of Non-germline and Germline Retinoblastoma Tumors

|

|

Non-germline

|

Germline

|

|

No 2nd nonocular cancers

|

Life risk of 2nd nonocular cancers

|

|

Later presentation

|

Earlier presentation

Risk bilateral and multifocal disease

|

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of retinoblastoma is clinical and no imaging or biopsy is needed.

B-Scan ultrasonography shows an intraocular mass with the following characteristics:

- High reflectivity

- High focal signals within the mass

- Orbital shadowing behind the mass

Pathology

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNAB) is contraindicated in intraocular disease to avoid extraocular spread of the tumor and is only considered in rare instances by an experienced ocular oncologist.

- There are reports that in some areas of sub-Saharan Africa, oncologists, unaware of the risk, require a tissue diagnosis to initiate treatment, making the accuracy of clinical introcular diagnosis essential. (Africa only)

- Neuroimaging is not necessary to make the diagnosis.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI):

- Tumours are usually dark compared with the vitreous in T2-weighted imaging and slightly hyperintense to the vitreous on T1-weighted imaging.

- In contrast to retinoblastoma, subretinal exudates on T2-weighted imaging in Coats disease appear bright and usually are dark in eyes with retinoblastoma.

- Computed tomography is avoided if MRI is available to avoid radiation exposure; however, scans show intraocular masses with areas of focal high attenuation from calcium.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Retinoblastoma is a clinical diagnosis based on ophthalmic exam and ancillary testing. See Table 4 for signs and symptoms of retinoblastoma.

|

Table 4. Signs and Symptoms of Retinoblastoma

|

|

Children under 5 years of age

|

Children over 5 years of age

|

|

Leukocoria (~60%)

|

Leukocoria (~35%)

|

|

Strabismus (~20%)

|

Strabismus (~15%)

|

|

Ocular inflammation (~5%)

|

Decreased vision (~35%)

|

|

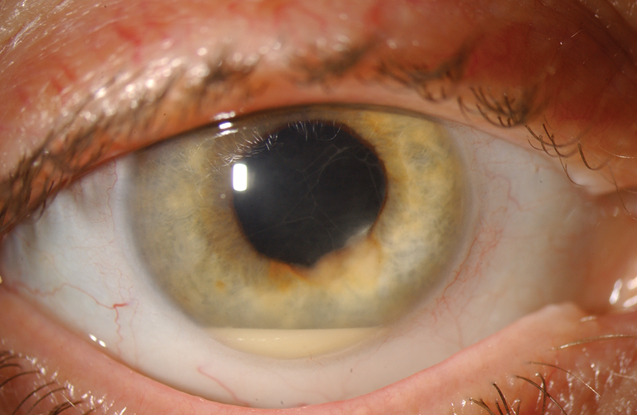

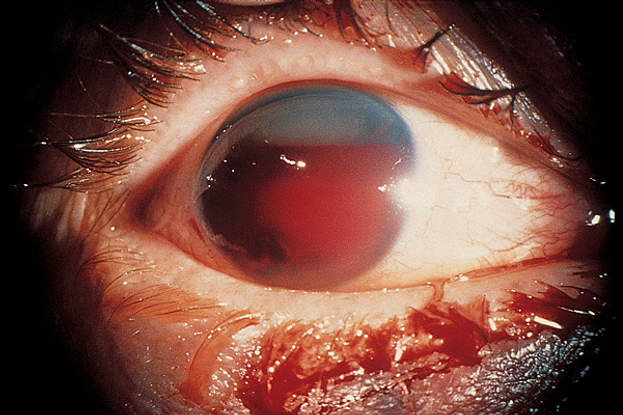

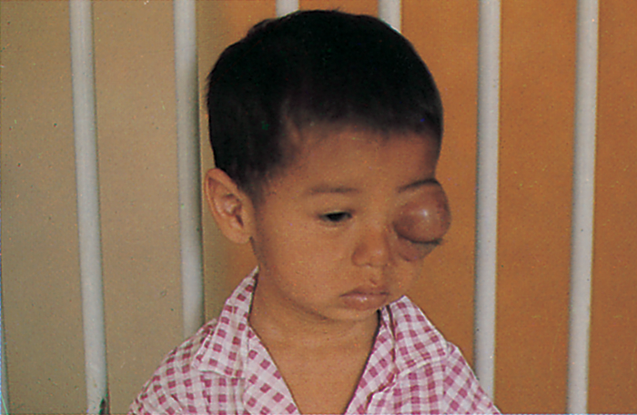

Less common: hypopyon (Figure 10), hyphema (Figure 11), iris heterochromia, spontaneous globe perforation, proptosis (Figure 12), cataract, glaucoma, nystagmus, tearing, anisocoria, poor vision

|

Less common: floaters, pain

|

MANAGEMENT

- Classification of retinoblastoma is important for making correct treatment decisions.

- Multiple classification schemes exist (Table 5, Table 6).

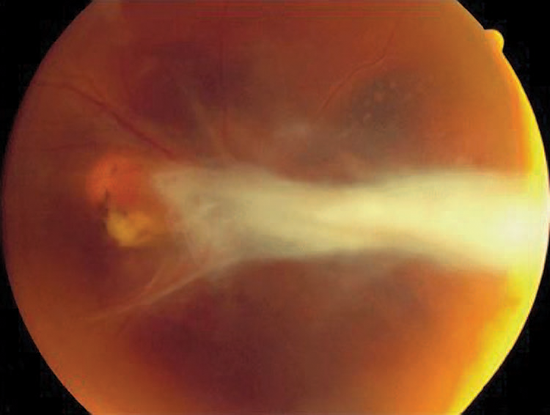

- See Chart 1 for a treatment summary based on classification.

Table 5. Reese-Ellsworth Classification of Retinoblastoma for Eye Preservation With Radiation

|

|

Group

|

A

|

B

|

|

I (very favorable)

|

Solitary tumor 4 disc diameters (DD) at or behind equator

|

Multiple tumors 4 DD at or behind equator

|

|

II (favorable)

|

Solitary tumor 4–10 DD or behind equator

|

Multiple tumors 4–10 DD or behind equator

|

|

III (doubtful)

|

Any lesion anterior to equator

|

Solitary tumor > 10 DD posterior to equator

|

|

IV (unfavorable)

|

Multiple tumors, some larger than 10 DD

|

Any lesion anterior to ora serrate

|

|

V (very unfavorable)

|

Massive tumor occupying half or more of retina

|

Vitreous seeding

|

Reproduced, with permission, from Rosa RH. Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 4, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

|

Table 6.

International Classification of Retinoblastoma (ICRB)

|

|

Group A

|

Small tumors (≤3 mm) confined to the retina; >3 mm from the fovea; 1.5mm from the optic disc

|

|

Group B

|

Tumors (>3 mm) confined to the retina in any location, with clear subretinal fluid ≤6 mm from the tumor margin

|

|

Group C

|

Localized vitreous and/or subretinal seeding (<6 mm in total from tumor margin). If there is more than 1 site of subretinal/vitreous seeding, then the total of these sites must be <6 mm.

|

|

Group D

|

Diffuse vitreous and/or subretinal seeding (>6 mm in total from tumor margin). If there is more than 1 site of subretinal/vitreous seeding, then the total of these sites must be ≥6 mm. Subretinal fluid >6 mm from tumor margin.

|

|

Group E

|

No visual potential; or

Presence of any 1 or more of the following

- Tumor in the anterior segment

- Tumor in or on the ciliary body

- Neovascular glaucoma

- Vitreous hemorrhage obscuring the tumor or significant hyphema

- Phthisical or pre-phthisical eye

- Orbital cellulitis-like presentation

|

Reproduced, with permission, from Rosa RH. Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 4, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

Chart 1. Treatment summary based on classification. See Image Library for figures referenced.

Priorities of Therapy

- Preservation of life and curing retinoblastoma

- Globe salvage

- Retention of vision

Internationally, the first step of management is to determine if there is disease spread outside the eye (ie, extraocular spread). With extraocular spread either via extension through the sclera or more commonly invasion of the optic nerve, survival rates decrease to less than 50%.

Management of Intraocular Retinoblastoma

- Photocoagulation/hyperthermia/transpupillary thermotherapy (TTT)

- Cryotherapy

- Curative enucleation

- Plaque radiotherapy (brachytherapy)

- Chemoreduction

- Intravenous chemotherapy

- Local chemotherapy (sub-Tenon’s injection)

- Intravitreal chemotherapy

- External beam radiation therapy (EBRT)

- Ophthalmic artery chemosurgery (OAC)

Management of Extraocular Retinoblastoma

- Intensive chemotherapy

- Radiation

- Bone marrow transplantation

- Surgical debulking

Follow-Up

- Enucleation is a curative therapy for unilateral, non-germline cases of retinoblastoma without extraocular extension.

- In children who have undergone any eye-sparing therapy, follow-up examinations every 6–8 weeks are required to document tumor regression.

Second Tumor Risk

- Osteogenic sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and melanoma are the most common secondary tumors associated with retinoblastoma. Table 7 summarizes secondary nonocular tumor risk from external beam radiation therapy.

- No standardized protocols to screen for second cancers.

- Some recommend yearly MRI of brain and dermatologic examination

- Some advocate annual full-body MRI scans for long bone evaluation

|

Table 7. Secondary Nonocular Tumor Risk From External Beam Radiation Therapy

|

|

Treatment without EBRT

|

~25% risk of second tumor development within 50 years

|

|

Treatment with EBRT

|

Decreased latency to development of first tumors

Increased incidence of tumors in first 30 years of life

Increased proportion of tumors in the field of EBRT

|

IMAGE LIBRARY

Differential Diagnosis

Figure 1. Coats disease. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 2. Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous/persistent fetal vasculature. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 3. Ocular toxocariasis.(© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 4. Retinocytoma. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 5. Congenital cataract. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 6. Retinopathy of prematurity. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of Colin A. McCannel, MD.)

Figure 7. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 8. Choroidal coloboma. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Courtesy of Damien Luviano, MD, FACS, and Mohammad Khan)

Pathophysiology/Definition

Figure 9. Genetics of retinoblastoma. (Reproduced, with permission, from Rosa RH. Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 4, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Chart created by David H. Abramson, MD.)

Signs and Symptoms

Figure 10. Sterile hypopyon. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 11. Hyphema. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 12. Proptosis. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.).

Management

Figure 13. Retinoblastoma. (Reproduced, with permission, from Rosa RH. Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 4, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Courtesy of Matthew W. Wilson, MD.)

Figure 14. Retinoblastoma, clinical appearance. Proptosis caused by retinoblastoma with orbital invasion. (Reproduced, with permission, from Rosa RH. Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 4, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

REFERENCES

Abramson DH. Retinoblastoma in the 20th century: past success and future challenges the Weisenfeld lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2683–2691.

Abramson DH, Schefler AC. Update on retinoblastoma. Retina. 2004;24:828–848.

Bowman RJ, Mafwiri M, Luthert P, Luande J, Wood M. Outcome of retinoblastoma in east Africa. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:160–162.

Canturk S, Qaddoumi I, Khetan V, et al. Survival of retinoblastoma in less-developed countries impact of socioeconomic and health-related indicators. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1432–1436.

Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 4. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2011–2012.

Rodriguez-Galindo C, Wilson MW, eds. Retinoblastoma, Pediatric Oncology. DOI 10.1007/978-0-387-89072-2_2, New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 2010.

Schefler AC, Abramson DH. Retinoblastoma: what is new in 2007–2008. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19:526–534.

CONTRIBUTORS

Executive Editor: R. V. Paul Chan, MD, FACS, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Section Editors:

Europe:

Christiane Isolde Falkner-Radler, MD, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Retinology and Biomicroscopic Laser Surgery, Vienna, Austria

Assistant Editors:

Swetangi D. Bhaleeya, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Kristin Chapman, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Peter Coombs, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Michael Klufas, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Samir Patel, medical student, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Region Contributor:Sophie Plainer, MD, Ophthalmology Resident, Department of Ophthalmology, Klinikum Klagenfurt, Klagenfurt

Copyright © 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology®. All Rights Reserved.