EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- Trachoma is the most common infectious cause of blindness worldwide.

- It occurs in developing countries in areas of poor sanitation and crowded conditions.

- Global prevalence of active cases of trachoma has decreased from 146 million in 1995 to 84 million in 2007.

- Trachoma is most commonly found in large parts of Africa (particularly Ethiopia and Sudan), the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, South-East Asia, and South America.

- Trachoma is relatively rare in the United States except in areas of the South and on Native American reservations.

- The Trachoma Atlas is an excellent resource for evaluating the prevalence of trachoma throughout Asia, Latin Americas, Africa and the Middle East. (www.trachomaatlas.org). Another excellent resource is Professor Hugh R. Taylor’s book, Trachoma: A Blinding Scourge from the Bronze Age to the Twenty-first Century. (East Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Eye Research Australia, 2008.)

Regional Information (Europe)

- Trachoma was once endemic in Europe but disappeared because of improved living standards.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- Chronic follicular conjunctivitis

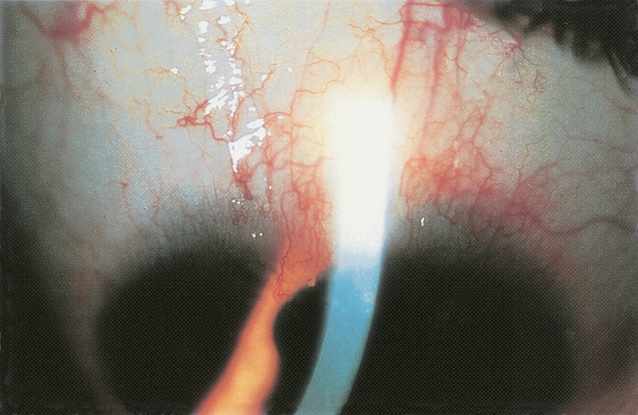

- Chlamydia inclusion conjunctivitis (Figure 1)

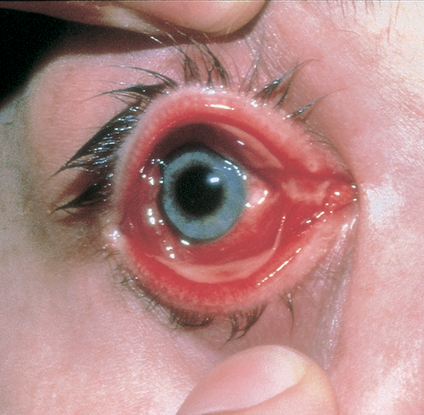

- Viral conjunctivitis (adenovirus) (Figure 2)

- Bacterial conjunctivitis (Moraxella, Staphylococcus aureus)

- Molluscum contagiosum

- Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis

- Toxic conjunctivitis/medicamentosa

- Parinaud oculoglandular conjunctivitis (Figure 3)

- Silent dacryocystitis

- Contact lens–related problems

- Other causes of entropion and trichiasis

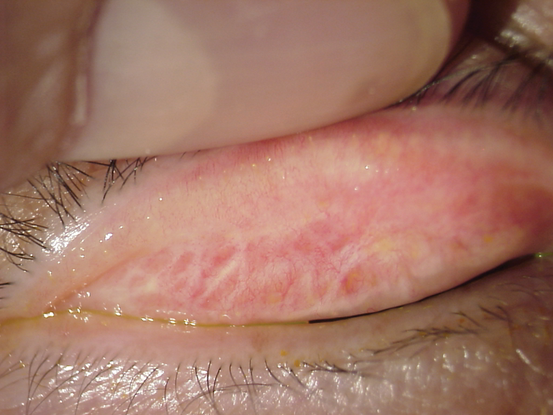

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome (Figure 4)

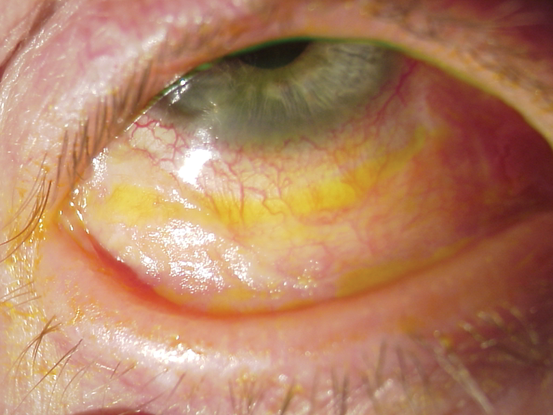

- Mucous membrane pemphigoid (Figure 5)

- Systemic sclerosis (Figure 6)

- Chemical injury and drugs

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY / DEFINITION

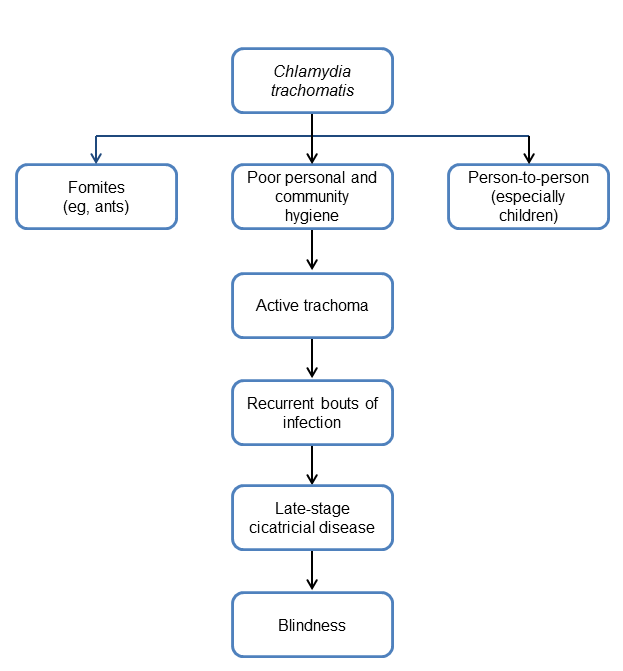

Chart 1. Pathophysiology.

Key Points

- Trachoma is an infectious disease (obligate intracellular, gram-negative bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis).

- Extracellular elementary body is infectious.

- Most infections are transmitted eye-to-eye, in close direct contacts via discharge from the eye and nose.

- A key cause of transmission is person to person. For example, mother to child or child to child.

- Transmission may also occur via flies (Musca sorbens) or other household fomites.

SIGNS, SYMPTOMS

World Health Organization Classification

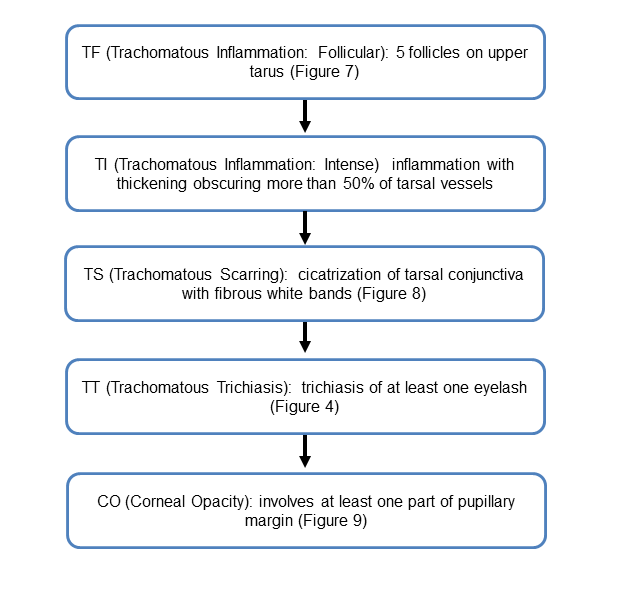

The World Health Organization developed 5 classification criteria for use by trained personnel other than ophthalmologists to assess prevalence and severity in population-based surveys in endemic areas (Chart 2).

Chart 2. World Health Organization classifications of trachoma. See the Image Library for selected figures.

Signs

- Follicular conjunctivitis (Figure 7)

- In acute trachoma, follicles on superior tarsus are obscured by diffuse papillary hypertrophy and inflammatory cell migration

- Arlt’s line (linear or stellate scarring of superior tarsal conjunctiva) (Figure 8)

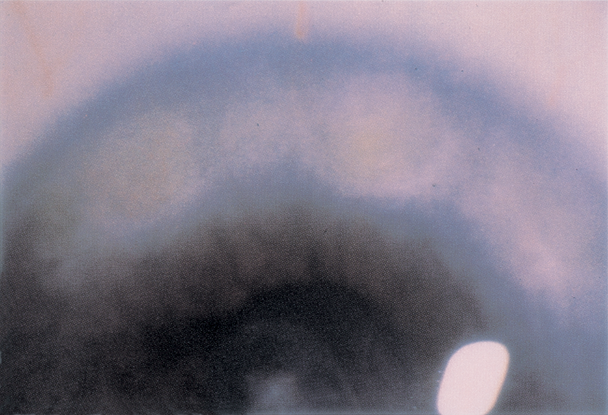

- Herbert’s pits (depressions in superior limbus due to involution and necrosis of follicles) (Figure 9)

- Corneal findings: epithelial keratitis, focal multifocal peripheral and central stromal infiltrates, and superficial fibrovascular pannus (most prominent in superior one-third of the cornea)

- Late stage (cicatricial) from severe conjunctival and lacrimal duct scarring: aqueous tear deficiency, tear drainage obstruction, trichiasis, entropion

Symptoms

- Foreign body sensation

- Eye redness

- Tearing

- Mucopurulent discharge

- Chronic duration of symptoms (>4 weeks)

MANAGEMENT

Workup

- History of exposure to endemic areas?

- Slit lamp examination

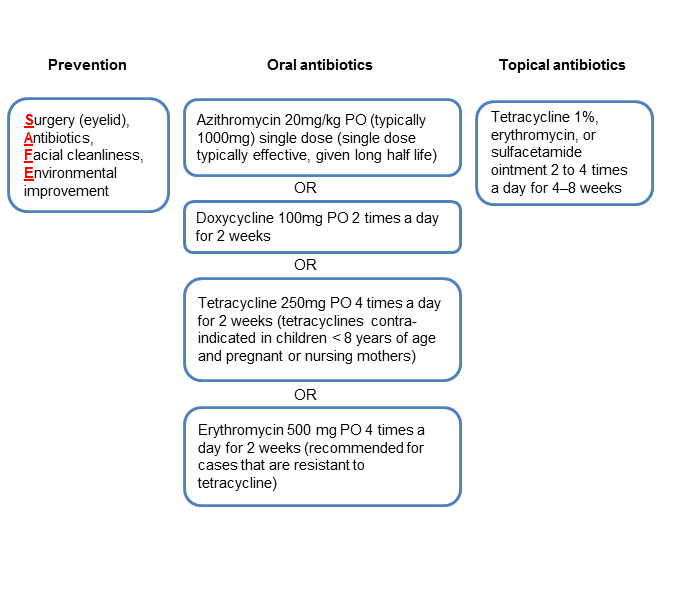

Treatment

Chart 3. Management recommendations.

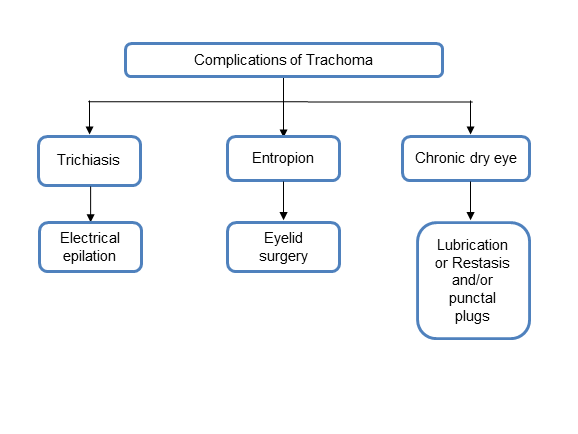

Complications and Their Management

Chart 4. Complications and their management.

CASE STUDY

A 34-year-old woman, an immigrant from Ethiopia currently working and living in the United Sates and having no past medical history, began experiencing redness, itchiness, tearing, and foreign body sensation in her right eye more so than the left eye for the past year. She had occasional mucopurulent discharge. She went to a doctor in the emergency room who prescribed gentamicin eye drops that have not provided resolution of symptoms. Symptoms of redness and discharge would last for a few weeks and then disappear. Over the past year, she has had 5 episodes of the redness and discharge as described and she noticed worsening visual acuity. She presented to the eye clinic for further evaluation.

Examination

- Visual acuity: 20/25 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye

- Pupil exam: PERRL OU, no APD

- Intraocular pressure: 12 mmHg OU

- Confrontational fields: Full OU

- Extraocular muscles: Full OU

Slit lamp examination

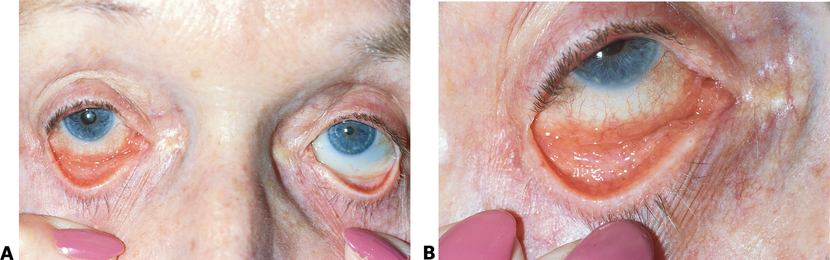

- Lids and lacrimal system: No significant trichiasis of the upper and lower lids OU (refer to Figure 8)

- Conjunctiva: Follicular reaction with Arlt’s line seen (linear scarring of superior tarsus) on everted lids OU, no mucopurulent discharge but tear meniscus was low OU (refer to Figure 9)

Cornea: Diffuse punctate epithelial erosions, superior limbal depressions (Herbert’s pits) OU; superior vascular pannus OU, no significant central corneal scarring OU

- Iris: Round and reactive OU

- Lens: Clear OU

Dilated fundus exam

- Optic nerve, macula and vessels on dilated examination were unremarkable.

Diagnosis

- Despite her currently living in the United States, given the patient’s origin from an area hyperendemic area for trachoma and pathognomonic clinical exam findings, the leading etiology for this chronic, follicular conjunctivitis is trachoma.

- A conjunctival swab/culture for PCR can be considered to evaluate for Chlamydia serotypes (serotypes A-C) that would be consistent with Chlamydia trachomatis.

- The patient has moderately advanced disease with signs of tarsal scarring, but no significant aberrant eyelashes and is without corneal opacification.

Treatment

- Single dose of azithromycin 1g

- Topical ointment 2 to 4 times a day for 4–8 weeks

- Artificial tears to use 4 times a day in both eyes as needed for dry eye

- Aberrant lashes/trichiasis

- If clinically significant entropion has developed from conjunctival and tarsal scarring, consider surgical repair to prevent cornea scarring/opacification.

Follow-Up

- She was lost to follow-up but returned to clinic 6 months later with no further episodes of conjunctivitis, and improved symptoms.

- Her acuity improved to 20/25 OU.

- Her follicular reaction had resolved, but she still had an Arlt’s line in both eyes.

- She continued to be without significant entropion or trichiasis and there was no evidence of significant corneal scarring.

IMAGE LIBRARY

Differential Diagnosis

Figure 1. Chronic follicular conjunctivitis. Chlamydia inclusion conjunctivitis. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 2. Viral conjunctivitis (adenovirus). (Reproduced, with permission from Weisenthal RW. External Disease and Cornea. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 8, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

Figure 3. Parinaud oculoglandular conjunctivitis. (Reproduced, with permission from Raab EL. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 6, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

Figure 4. Stevens-Johnson syndrome. (Reproduced, with permission from Weisenthal RW. External Disease and Cornea. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 8, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

Figure 5. Stevens-Johnson syndrome. (Reproduced, with permission from Weisenthal RW. External Disease and Cornea. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 8, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

Figure 6. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. (Reproduced, with permission from Weisenthal RW. External Disease and Cornea. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 8, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

File Name: trac6

Signs, Symptoms

Figure 7. Follicular conjunctivitis. A. Inflammation of the right eye from glaucoma medication. B. Right eye showing follicular conjunctivitis in the inferior fornix . (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 8. Arlt’s line (linear or stellate scarring of superior tarsal conjunctiva). (Reproduceded, with permission from Weisenthal RW. External Disease and CorneaBasic and Clinical Science Course, Section 8, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014.)

Figure 9. Herbert’s pits (depressions in superior limbus due to involution and necrosis of follicles (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

REFERENCES

Burton MJ. Trachoma: an overview. Br Med Bull. 2007;84:99–116.

Burton MJ, Mabey DC. The global burden of trachoma: a review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e460.

External Disease and Cornea. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 8, 2011–2012. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2011.

Friedberg M, Rapuano C. Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 5th ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2008.

Lewallen S, Courtright P. Blindness in Africa: present situation and future needs.Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:897–903.

Mariotti SP, Pascolini D, et al. Trachoma: global magnitude of a preventable cause of blindness. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:563–568.

Mathew AA, Turner A, Taylor HR. Strategies to control trachoma. Drugs. 2009;69:953–970.

Taylor HR. Trachoma: A Blinding Scourge from the Bronze Age to the Twenty-first Century. East Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Eye Research Australia, 2008.

The Trachoma Atlas. Available: www.trachomaatlas.org. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Whitcher JP, Srinivasan, Upadhayay. Corneal blindness: a global perspective. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:214–221.

Wright HR, Turner A, Taylor HR. Trachoma. Lancet. 2008;371:1945–1954.

CONTRIBUTORS

Executive Editor: R. V. Paul Chan, MD, FACS, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Section Editors:

Europe:

Christiane Isolde Falkner-Radler, MD, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Retinology and Biomicroscopic Laser Surgery, Vienna, Austria

Assistant Editors:

Swetangi D. Bhaleeya, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Kristin Chapman, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Peter Coombs, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Michael Klufas, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Samir Patel, medical student, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Copyright © 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology®. All Rights Reserved.