During the COVID-19 quarantine, five-year-old Joey Spiesman did his best to sit still for virtual kindergarten at home. He burned off energy outside with his soccer ball and kept his parents on their toes with his sharp sense of humor.

That’s why they thought Joey was kidding when he sat in front of a letter chart at an eye exam, with one eye covered, and said, “I can’t see anything!” But he wasn’t teasing. Although Joey’s left eye had 20/20 vision, his right eye was nearly blind.

“We were shocked,” reflected Pamela Spiesman, Joey’s mom. “He did everything that kids with normal vision do and never complained.”

Joey had been referred for an ophthalmology exam after coming up short of 20/20 at his annual pediatric vision screen. His parents had also missed a telltale sign of blinding eye disease; a yellowish glow in his right eye that showed up in photographs.

Childhood is a crucial time for developing healthy vision and symptoms of eye problems in children aren’t always obvious. Regular eye screenings are essential to catching and correcting problems before they lead to irreversible vision loss.

Diagnosing a rare eye condition called Coats’ disease

Joey was referred to Duke University Eye Center, where vitreoretinal specialist Cynthia Toth examined his retina, the light sensitive tissue at the back of the eye.

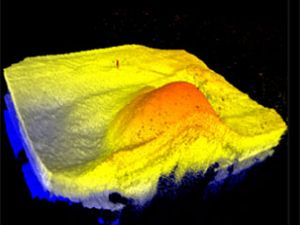

“Joey had a large deposit of yellow, chicken-fat-like material in the center of his vision, leaking blood vessels and a retinal detachment. These are classic signs of Coats’ disease,” said Cynthia Toth, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and biomedical engineering.

Coats’ disease is a rare eye disorder where blood vessels that provide essential blood and oxygen to the retina develop irregularly. In affected people, blood vessels form aneurysms and leak fluid into the back of the eye. The fluid can build up, causing the retina to swell and vision to decline. It can also accumulate beneath the retina and trigger a retinal detachment. If the condition is caught early enough, some lost vision can usually be returned.

Catching Coats' disease early is difficult — but important

Coats' disease almost always affects only one eye. It's far more common in boys than girls. And it's very easy to overlook.

The disease tends to progress gradually. And because one of the child's eyes works normally, children rarely complain — even though their vision may be deteriorating. Children may also have a hard time finding the words to explain their symptoms.

Signs and symptoms include:

- Yellow eye or yellow or white glow in flash photography (similar to red eye)

- A white appearance when looking at the pupil (the dark spot in the center of the iris) of the eye

- Loss of vision

- Eye turning outward or inward (strabismus)

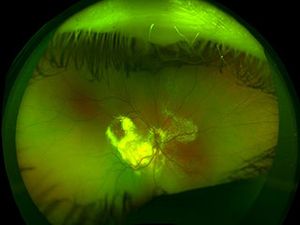

“When we looked back at photographs of Joey in 2020, we found more than one with the yellow glow showing in his right eye,” said Pamela. One of those photos is shown above. A white or yellow glow in photos of a child’s eye can be an indicator of Coats’ disease or another serious eye problem and should be checked out by an ophthalmologist right away.

Aggressive treatment can stop vision loss from Coats' disease

Treatment for Coats’ disease can take one to three years to stabilize the eye. Joey needed a combination of laser surgery and steroid and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections to shrink abnormal blood vessels, quiet inflammation, stop leaking and reduce the growth of abnormal new blood vessels. These procedures were repeated several times over the course of a year.

The treatments succeeded in halting the disease and reversing some of Joey’s vision loss. By March 2022, Joey’s vision had improved ten-fold, and he is now able to read large letters on the eye chart. Despite this, Joey will always have a little lump in the center of his retina that will limit his central vision. Doctors are still learning why this occurs in some patients with the disease.

In a photo of Joey's retina from early 2021 (left), the fatty deposit is large and already has a dome shape (shown in 3D on the right). Joey's eyelashes are visible in the top and bottom of the retinal photo.

By 2022, after aggressive treatment, the fatty deposit has mostly cleared up. A small yellow bump remains.

Growing up with Coats' disease

Joey’s eyes will need to be monitored every six months for the next couple of years, but that hasn’t slowed him down one bit.

“He’s a pistol!” says Dr. Toth. Joey still plays soccer, and also takes pitches for the Blue Jays, his local little league team. He’s also an avid reader of the Dog Man comic books.

Because Joey’s eyes are still growing, he wears a patch for a couple of hours each day to help remind his brain to use input from both eyes. He will always have limited central vision in his right eye, which means he likely won’t be a fighter jet pilot or a commercial truck driver. He’ll need to wear glasses, mainly to safeguard his eyes from injury, and protective head gear when he plays sports. Otherwise, with 20/20 vision in his left eye and strong peripheral vision in his right eye, the sky’s the limit, said Dr. Toth.

Joey’s parents are grateful. “We feel lucky that Joey’s out of danger of losing his eye and are thankful that Dr. Toth helped him regain vision,” said Pamela.