Steven T. Charles, MD, is an icon in the world of retina. “As someone who has practiced in the retinal field for 30 years, I can unequivocally state that Dr. Charles’ instruments, techniques, and thought processes assist me daily in immeasurable ways and have helped me to save many eyes,” said John C. Hoskins, MD, president of the Tennessee Academy of Ophthalmology. “He is inherently blessed with a brilliant mind, and it’s difficult to truly measure his contributions to our field because, unquestionably, they are profound.”

The 3 T’s

Dr. Charles is the first person to admit that he’s not good at everything ophthalmologic. “I literally don’t know how to do any coding or billing. I just tell our people in the office, ‘Go to the meetings, play by the rules, and learn how to do it.’” What he does pride himself on are the 3 T’s: technique, technology, and teaching. “The 3 T’s are intertwined,” he said. “Developing a new surgical technique is dependent on also developing a technology that enables performance of the technique. And so I believe in teaching technique and technology together— focusing on concept learning, which is robust and useful, as opposed to content learning, which is rote, fragile, and more difficult to apply.”

These 3 T’s are in his blood and have been the driving force of his career. Dr. Charles’ father was a college professor, his maternal grandfather was an engineer, and his paternal grandfather and uncle were both surgeons. Accordingly, it’s quite natural that his career transpired the way it did. After graduating high school, he attended 4 years of engineering school—an experience that would greatly inform his career as an ophthalmologist. “Being a cabinetmaker, a machinist, a welder, and an electronics technician as a young man, I knew I wanted to work with my hands,” said Dr. Charles. “But it wasn’t until about halfway through engineering school that I started to think about being a doctor.” Dr. Charles cut his program short and, in 1965, enrolled in medical school at the University of Miami, where he conducted research at the fledgling Bascom Palmer Eye Institute under the guidance of Edward W.D. Norton, MD. After a medical internship and residency in ophthalmology at Jackson Memorial Hospital, he served as a clinical associate at the National Eye Institute in 1973. Today he is a clinical professor at the University of Tennessee and runs the Charles Retina Institute.

On Innovation

The list of surgical techniques that he has developed traces the entire history of vitrectomy: endophotocoagulation, fluid-air exchange, forceps membrane peeling, scissors segmentation and delamination, linear suction, and punch-through retinotomy for subretinal bands, to name just a few.

Despite it all, he has never been interested in the “fame game.” Eschewing what he calls “aspirational innovation,” his singular focus is on how collaboration with others can push forward innovation that will truly help patients. “Innovation doesn’t come about because it’s something you plan, want, or hope for,” said Dr. Charles. “You’ve got to roll up your sleeves and work. I haven’t taken a vacation in 22 years.” Even though Dr. Charles does not have a life of luxury, he does have friends around the world, and it’s the collaboration with these colleagues that fuels his accomplishments. “We can’t be obsessed with money or the fame game or naming an instrument after ourselves—nothing good comes from that because few innovations are actually the result of a single individual. But if multiple surgeons and multiple engineers collaborate, this working together will keep our focus on our patients and their outcomes.”

What’s truly important about innovation, said Dr. Charles, is getting a product into widespread clinical use. “I’m always learning technology at the highest level so that I can really engage in high-volume, unmet clinical needs. Of course, it’s rewarding to focus on curing the rare diseases that affect small amounts of people with a specific genetic disorder. But our biggest technological breakthroughs in the past have come from—and into the future, will come from—improvements in managing the common diseases that we typically manage poorly: glaucoma, macular degeneration, proliferative vitreoretinopathy.”

A Defining Moment

Dr. Charles performing vitreoretinal surgery.

Dr. Charles has been instrumentally involved in engineering the earliest vitrectomy surgical systems, and he remains involved by refining present-day systems. He has more than 100 issued or pending patents. He was the founder of MicroDexterity Systems, which developed robots to aid in spine surgery and minimally invasive knee and hip replacement. He is also the cofounder of CamPlex, a company pioneering advanced visualization technology for neurosurgery and the treatment of head and neck cancers.

But of all his achievements, Dr. Charles is most satisfied with his work at Alcon Laboratories, where he has served as the principal architect for the Accurus Surgical System and the Constellation Vision System—both of which have revolutionized vitreoretinal surgery. The Accurus and the Constellation aren’t his inventions, though; they came to fruition through many years of working with over 100 engineers. This collaboration culminated in a moment that he has never forgotten—a moment when the 3 T’s came together to push the limits of patient care. For Dr. Charles, it’s a moment that encapsulates his career.

“Years ago, I went on a trip to Beijing to assist a team of ophthalmologists with the Accurus system. They had a giant waiting list for surgeries and were more than 2 years behind. I asked them, ‘How many cases do you do a day?’ They said 2. ‘How many employees do you have in the OR?’ They said 25. I replied, ‘I have 1 scrub tech and 1 circulating nurse, and I do 12 cases a day. I’m done by 5:30. Let me show you how.’ So rather than travel around to the Great Wall and all of the tourist spots during my stay, we operated all day every day. I don’t believe in rest— it’s bad for you—so I did 42 cases in a week in their OR.”

But that wasn’t the most rewarding part, said Dr. Charles. “What was truly fulfilling was when I returned a few years later, they had huge smiles on their faces as they posed in front of the Accurus machine that I helped develop and showed me ‘the list.’ They were now doing 10 cases a day, and their backlog was almost gone. Now that’s cool—being able to apply what I’ve learned in engineering to retinal surgery and to design good things for real people with real problems.”

For Dr. Charles, this story is also a reminder of the power of efficiency in ophthalmology. “When I departed, I told my Beijing colleagues that if you set out to perform ‘show-off ’ procedures that take an hour, there’s no lasting value. Instead, focus on the middle-of-the-road cases— not the easiest and not the hardest—and do them quickly and efficiently. That’s how we can truly save time, money, and, most importantly, vision

Two Traits for Success

Reflecting on 5 decades in medicine, Dr. Charles has identified 2 traits common to the most successful physicians. The first is emotional intelligence. This concept gained popularity in 1995 from the best-seller Emotional Intelligence by science journalist Daniel Goleman. “It’s especially important for a physician,” said Dr. Charles. “This type of intelligence comes down to being aware of your own emotions as well as those of others and managing these emotions to achieve your goals. To be good in business, for example, you need to sense buyer anxiety and sales resistance. In the case of medical outcomes, it’s especially important to read patients and empathize with and sense what they are feeling.”

Emotional intelligence is common parlance in the medical world, but there’s another important character trait that not enough physicians focus on, said Dr. Charles. It’s the idea of robustness. This concept has its roots in engineering and involves feedback loops that ensure stability despite changing variables.

“Think of a large, empty building,” said Dr. Charles. “Five hundred people enter for a meeting, yet the building temperature remains the same—feedback sensors in the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system are continuously making adjustments to keep things stable. Now apply this in human terms. It’s shocking how many people are effective until they happen upon a stressful event. They just aren’t able to make the necessary adjustments to remain competent in what they are performing. But to be successful, you have to. I can’t be rattled or upset in the OR; if I am, I’m going to hurt somebody or blind them. We can’t let things knock us down, be it illness, divorce, business failures, or whatever stands in our way.”

Dr. Charles’ favorite metaphor for this idea of robustness is one he learned from a college friend who played wide receiver at the University of Oklahoma. “No matter how well he was covered by how many opponents, he’d yell at his quarterback, ‘Give me the ball. I’m wide open!’ I’ve told my colleagues the same thing my entire career. It doesn’t matter if it’s patient care or working to get the latest technology to market. ‘Don’t worry.’ ‘Give it to me.’ ‘I can handle this.’”

Looking Ahead

Dr. Charles doesn’t have plans to retire anytime soon. He’s currently engaged in 3 large projects: as an engineer for Alcon’s fifth-generation vitreoretinal machine; as the main surgeon for the National Eye Institute’s iPSC project, coaxing induced-pluripotent stem cells into retinal pigment epithelium for surgical implantation; and as a developer of new visualization technology for retinal physicians in the operating room.

Looking ahead, he sees a bright future for ophthalmology. But to fulfill that future, said Dr. Charles, ophthalmologists young and old should reflect on 1 thing: simply being a good doctor. This means attending as many meetings as possible, reading journals, and getting to know other surgeons. This also means worrying less about money and reimbursement.

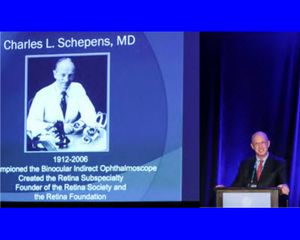

Dr. Charles delivers the Retina Society’s 2016 Schepens Lecture.

“As a whole, we should concern ourselves less with the business side of ophthalmology and focus more on practicing state-of-the-art medicine. And you can’t achieve that by constantly worrying about coding or billing or hanging out in your clinic. You’ve got to attend the big ophthalmic gatherings, listen to the top surgeons talk, ask questions, and watch people operate so that, collectively, we all improve each other’s skill sets.” For Dr. Charles, the expression “a rising tide lifts all boats” rings especially true. “A tremendous number of physicians isolate themselves in their offices, clinics, and operating rooms. Instead, let’s get out and learn together. Let’s pay attention to the pace of technological development. Let’s take more active risks—no more paralysis by analysis. Let’s work with device manufacturers and the people who are going to make the next-generation biologics. Let’s improve one another’s craft. After all, ophthalmology is a lifetime education. It’s not about the golf games, the wine collections, and the Ferraris. We are here to devote our energy to making patients see better and to producing better outcomes. And you know what? It’s fun!”

Next story from AAO 2018—Update on Uveal Melanoma Case Clusters: John O. Mason III, MD, talks about "unique study populations" with uveal melanoma.