By Poorav Patel, MD, MHS, Michael Ang, MD, and Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS

Edited By: Steven J. Gedde, MD, MHS

Download PDF

Benjamin Beauchamps,* a 65-year-old man, was experiencing an insidious onset of decreased vision in his right eye. As an engineer, he was attentive to detail. He had visited several ophthalmologists, complaining of a 10% to 15% reduction of vision in that eye. When pressed to provide more details, he said that images appeared “pixelated.” At the suggestion of his primary ophthalmologist, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with and without contrast was ordered. It was read as normal.

We Get a Look

When Mr. Beauchamps came to our ophthalmic plastic surgery clinic, he was at his wit’s end. Despite “normal exams” with multiple eye specialists, he insisted that he had decreased vision. His past ocular history was notable for ocular hypertension. To our surprise, he pulled out an Amsler grid on which he had drawn a focal area of visual decline.

Exam. On examination, the patient’s visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes, and his intraocular pressure (IOP) with a Tonopen was 14 mm Hg bilaterally. We noted an extremely small upgaze restriction in his right eye, and Hertel exophthalmometry measured 2 mm of proptosis in the same eye (Fig. 1). Thyroid function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibody assay, rheumatoid factor levels, rapid plasma reagin, and complete blood count with differential were ordered. We asked Mr. Beauchamps to return with lab results and his initial MRI for us to review.

Follow-up. All lab results were within normal limits. Review of the MRI revealed an abnormal swelling in the area of the inferior rectus muscle. This might have been previously overlooked because an artifact from a tooth implant created a suboptimal image. Based on this new finding, we started the patient on an oral prednisone regimen with taper and ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of his orbits with and without contrast.

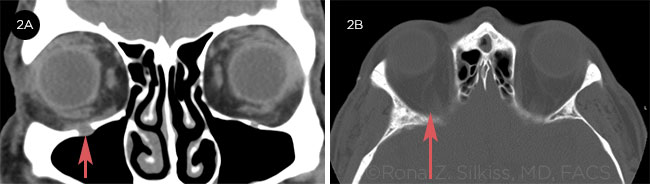

The scan. The CT scan showed an abnormally enlarged right infraorbital nerve (ION) with an enlarged, smoothly eroded canal along its entire visualized length, from the pterygopalatine fossa to the inferior orbital foramen (Fig. 2A). In addition, we observed thickening in the posterior aspect of the right inferior rectus muscle, extending to the orbital apex and likely impinging on the optic nerve (Fig. 2B).

|

|

PROPTOSIS. Hertel exophthalmometry measured 2 mm of proptosis in the patient’s right eye.

|

Differential Diagnosis

Although radiologic evidence demonstrated an orbital process likely contributing to his symptoms, which improved with steroids, we still did not have a diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included immunoglobulin (Ig)G4–related disease, reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH), and lymphoma.1

|

|

CT SCAN. (2A) Coronal CT scan shows right infraorbital nerve enlargement. (2B) Axial CT scan shows right inferior rectus impinging on the optic nerve.

|

Diagnosis and Treatment

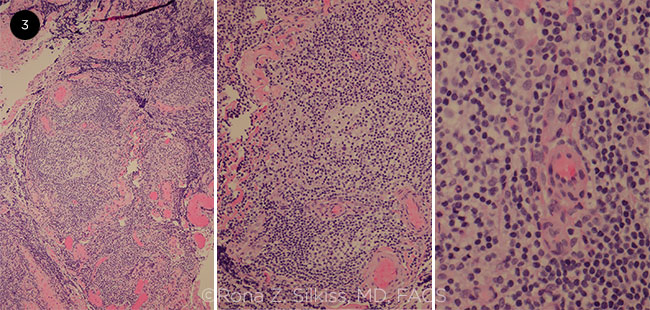

Mr. Beauchamps was then scheduled for a right anterior orbitotomy with biopsy. The biopsy with flow cytometry was consistent with a CD10-positive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, suggestive of low-grade follicular lymphoma (Fig. 3).

We referred Mr. Beauchamps to an oncologist, who performed a bone marrow biopsy, which showed no evidence of lymphoma or leukemia. (Notably, orbital lymphoma can occur in advance of or without systemic involvement.) Analysis revealed normal cytogenetics and negative flow cytometry. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan was performed; it revealed extensive fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid adenopathy from the neck through the pelvis, including the left proximal femur. It was unclear whether the adenopathy was related to lymphoma. Nonetheless, Mr. Beauchamps was treated with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommended therapy of bendamustine and obinutuzumab.2

|

|

SLIDES. (3) Histopathology of the biopsy was consistent with follicular lymphoma.

|

Discussion

Although follicular lymphoma was the diagnosis, the more interesting aspect of this case involved the ION enlargement. Enlargement of the ION has recently been described as strongly suggestive of IgG4 disease. However, it can also be seen in RLH and/or lymphoma.

Nomenclature. Of note, IgG4-related ophthalmic disease forms a significant portion of “idiopathic orbital inflammation” or RLH diagnoses.3,4 The nomenclature of this disease process is evolving, as outlined by McNab et al.3 Patients can also present with sinus disease and lacrimal gland enlargement.

ION enlargement. Hardy et al. describe ION canal enlargement in a retrospective case series of 14 patients taken from the orbital databases of Moorfields Eye Hospital and Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital. All 14 patients had ION canal enlargement with biopsy-proven chronic orbital inflammation. In seven cases, the pathology was suggestive of RLH. The biopsies in the remaining seven patients were consistent with IgG4-related sclerosing inflammation. Of those, six patients had serum elevation of IgG4. One patient developed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.5

RLH. RLH comprises less than 10% of periocular lymphoid lesions. Patients range in age from 23 to 80, with a mean age of 54.8, and they tend to present with an indolent, painless anterior orbital mass.5,6 The lesion cannot be clinically or radiologically differentiated from lymphoma, necessitating a histologic diagnosis. Patients with RLH are at high risk of developing lymphoma (50% progression rate). This may be attributed to chronic, antigen-induced inflammation, which can lead to the emergence of monoclonal lymphoma as seen in other systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis.5

Expansion of the ION and canal is rare and is highly suggestive of IgG4 disease. However, the differential includes lymphoma, sarcoidosis, perineural or endoneural tumor invasion, aspergillosis, neurofibroma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, schwannoma, cavernous hemangioma, and traumatic neuroma.5

Conclusion

Fortunately, Mr. Beauchamps continued to pursue a diagnosis, despite several apparently “normal” exams. He has been doing well on treatment, with regression of the disease and improvement of symptoms.

___________________________

*Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Watanabe T et al. Jpn J Radiol. 2011;29(3):194-201.

2 www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/nhl-follicular_lymphoma/files/assets/common/downloads/SurveyQuickGuide_waldenstroms.pdf.

3 McNab AA, McKelvie P. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(2):83.

4 McNab AA, McKelvie P. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(3):167.

5 Hardy TG et al. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(6):1297-1303.

6 Mannami T et al. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(7):641-649.

___________________________

Dr. Patel and Dr. Ang are ophthalmology residents, and Dr. Silkiss is chief of the Division of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. All are at the California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco and The Eye Institute in San Francisco. Financial disclosures: None.