By Tahira Scholle, MD, Mina Naguib, MD, Kanwal Matharu, MD, and John Chancellor, MD

Edited by Ahmad A. Aref, MD, MBA

Download PDF

Luis Aguilar* is a 31-year-old carpenter who was using a nail gun on a piece of wood when a splinter flew into his left eye. He immediately noted a foreign body sensation and a cloud coming over his vision. Worried, he went straight to the ER of a hospital that is outside of our network.

Initial Management at the ER

A first look at the wound. At the ER, the ophthalmologist on call examined Mr. Aguilar and noted a 4-mm full-thickness corneal laceration centrally with vitreous prolapse through the wound. Mr. Aguilar had a traumatic cataract and a 2-mm hyphema. There was no view to the retina. Computed tomography (CT) showed no intraocular foreign body.

Repair of the ruptured globe. The patient was given a tetanus shot, and the ophthalmologist repaired his ruptured globe. After vitreous was trimmed with Vannas scissors, the corneal laceration was closed with six 10-0 nylon sutures.

He was seen on post-op day 1, but no records were available from that visit.

Post-op day 3: Worsening inflammation. Mr. Aguilar was seen again at the same hospital on post-op day 3 and was noted to have increased inflammation. Vision was hand motion (HM), IOP was 20 mm Hg, and he had 2+ injection, a closed central corneal laceration that was Seidel negative, and 3+ Descemet folds. His hyphema had resolved, but he had a 0.5-mm hypopyon with 3+ fibrin in the anterior chamber. There was a poor view, but he was noted to have iris sphincter tears and a complete traumatic cataract.

Records for this visit noted that prednisolone acetate 1% drops were increased from every two hours to every hour and that he was continued on topical moxifloxacin, atropine, timolol, and brimonidine.

Because Mr. Aguilar did not have insurance, he was instructed to go to the county hospital ER so he could be evaluated by a retina specialist.

|

|

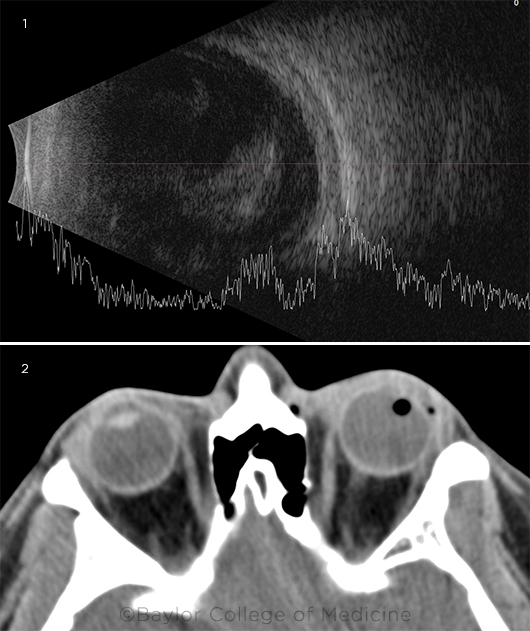

WHAT WE SAW. When Mr. Aguilar arrived at our ER, five days after the initial ruptured globe repair, (1) B-scan ultrasound showed vitritis. (2) CT orbit showed no radiopaque foreign bodies. Punctate foci of air in the vitreous cavity were consistent with recent ruptured globe.

|

We Get a Look

Post-op day 5: The patient arrives at our hospital. Two days later (five days post-op), Mr. Aguilar arrived at our county hospital ER, where he was examined by an ophthalmology resident and retina fellow.

Examination. Mr. Aguilar reported decreasing pain and poor vision, though the latter was stable. His visual acuity was still HM, and he was noted to have 1+ injection, corneal edema with Descemet folds, vitreous in the anterior chamber, a 1.5-mm hypopyon, and some nonlayered blood on the inferior iris, as well as a white cataract. Due to corneal edema and cataract, the retina could not be viewed.

Imaging. B-scan ultrasonography showed vitritis with an attached retina (Fig. 1). Because the CT performed at the outside hospital could not readily be obtained, a CT of the orbit without contrast was performed in our ER to rule out an intraocular foreign body. This showed no radiopaque foreign bodies, but it did show mild periorbital superficial swelling with punctate air foci in the lateral aspect of the vitreous cavity and in the left lateral preseptal soft tissue (Fig. 2), consistent with a recent ruptured globe.

Differential Diagnosis

Given the worsening hypopyon and vitritis on B-scan ultrasound in the setting of a recent ruptured globe, post-traumatic endophthalmitis was high on our differential diagnosis.

We also considered the possibility of a retained intraocular foreign body (IOFB). Although CT showed no radiopaque IOFB, wood can have various densities on CT due to type and hydration status and thus can be missed.1

Phacoantigenic uveitis was also high on the differential, as Mr. Aguilar had a known traumatic cataract and had less pain than typical for infectious endophthalmitis. However, the amount of vitritis on B-scan was greater than expected for phacoantigenic uveitis.

We also considered that the hypopyon could be a pseudohypopyon from dehemoglobinized red blood cells, as hyphema was noted at presentation. The hyperechoic areas on B-scan ultrasound could represent vitreous hemorrhage secondary to trauma, rather than vitritis.

Treatment

Given the potentially blinding nature of endophthalmitis, we decided to perform a vitreous tap and to inject intravitreal antibiotics. We advised Mr. Aguilar that surgery might be needed if the eye did not improve. The vitreous tap was dry, so an anterior chamber tap was performed subsequently. Vancomycin, ceftazidime, and voriconazole were injected intravitreally. We administered the antifungal agent, voriconazole, due to the history of injury with organic matter (wood).

Follow up after tap and inject. The following day, Mr. Aguilar’s vision remained HM. The hypopyon had decreased from 1.5 mm to 0.5 mm, but the exam and B-scan ultrasound findings were otherwise unchanged. The aqueous fluid gram stain showed 1+ white blood cells with no organisms, and cultures showed no growth. We started the patient on 60 mg of oral prednisone daily, and all the other topical agents were continued.

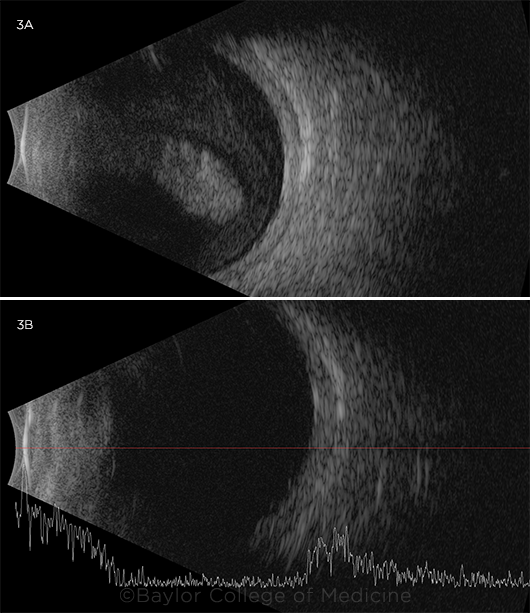

The decision to operate. The next day (two days after tap and inject), Mr. Aguilar’s vision and hypopyon were stable, and aqueous cultures continued to show no growth, but there was increased fibrin in the anterior chamber and worsened vitritis on B-scan ultrasound (Fig. 3A). Therefore, we performed an emergent pars plana vitrectomy, pars plana lensectomy, vitreous biopsy, and intravitreal injection of vancomycin, ceftazidime, and voriconazole.

|

|

FURTHER IMAGING. Two days after tap and inject, (3A) B-scan ultrasound showed increased density of vitritis. One day after we had performed vitrectomy and lensectomy, (3B) the view to the fundus was limited by corneal edema but the vitreous cavity appeared clear on ultrasound.

|

A Surprise in the OR

Intraoperatively, we had a very poor view owing to corneal edema and sutures through the central corneal laceration, so we scraped the corneal epithelium, sparing the area immediately around the laceration. Then we washed the fibrin and hypopyon out of the anterior chamber.

After a pupillary membrane was removed, we were expecting to see a traumatic cataract. We were surprised to see a torn capsular bag but no lens in the lens plane. Instead, there was dense, white vitritis immediately behind the capsule, which is what we had thought was a white cataract preoperatively. The vitrector was then used to clear the vitritis, and the vitreous fluid was sent for gram stain and cultures. As the vitritis was cleared, we saw that the cataractous crystalline lens was completely dislocated into the vitreous cavity. The vitrector was used to remove the lens, and Mr. Aguilar was left aphakic. Once the remaining vitreous and vitritis were cleared, there was an adequate view to the retina, which was attached and appeared healthy. Vancomycin, ceftazidime, and voriconazole were injected intravitreally.

Postoperative Course

Gram stain from the vitreous biopsy showed 2+ white blood cells. Bacterial and fungal cultures showed no growth after three weeks. By Mr. Aguilar’s three-week post-op visit, vision in the left eye had improved to 20/125 with a +11 lens and was deemed to be limited by aphakia, astigmatism from corneal sutures, and residual corneal edema. Mr. Aguilar noted continuing improvement in vision and decreased pain. IOP was 10 mm Hg with 1+ anterior chamber cell, no hypopyon, clear vitreous, and normal optic nerve and retina, with a limited view due to the corneal edema. B-scan ultrasound confirmed a clear vitreous cavity (Fig. 3B). We tapered his oral prednisone and atropine and stopped his timolol and moxifloxacin drops. Prednisolone drops were continued as part of normal post-op care.

Final Diagnosis

Mr. Aguilar was given the final diagnosis of phacoantigenic uveitis.

Lens-associated uveitis can be divided into phacolytic uveitis and phacoantigenic uveitis. Phacolytic uveitis is inflammation caused by leakage of lens protein through an intact lens capsule in mature or hypermature cataracts, whereas phacoantigenic uveitis is inflammation caused by lens proteins that have been released through a ruptured lens capsule.2

Phacoantigenic uveitis typically presents days to weeks after trauma or cataract surgery. Symptoms include a red, painful eye, anterior chamber cell, keratic precipitates, occasional hypopyon, and sometimes elevated IOP. Its former name, phacoanaphylactic uveitis, is no longer used because immunoglobulin E (IgE), which mediates true anaphylaxis, is not present.3

The diagnosis of phacoantigenic uveitis is supported by a traumatic cataract with a ruptured lens capsule, aqueous and vitreous cultures that show no growth, lack of significant improvement after intravitreal antibiotics/antifungals, and marked improvement after vitrectomy/lensectomy. We went back and reviewed Mr. Aguilar’s B-scans prior to vitrectomy/lensectomy (Figs. 1 and 3A) and determined that the more hyperechoic area was actually his dislocated traumatic cataract rather than a focal area of vitritis, as had been previously thought.

Because post-traumatic endophthalmitis can mimic phacoantigenic uveitis and can have dire consequences, patients may need to be treated for endophthalmitis until infection is ruled out. Definitive treatment for phacoantigenic uveitis consists of steroids and removal of the inciting lens material.4

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Fortenbach CR et al. Adv Ophthalmol Vis Syst. 2016;4(4):123-124.

2 Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 9. Uveitis and Ocular Inflammation. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2020-2021:136-137.

3 aao.org/pols-snippet/3218. Accessed Sept. 7, 2021.

4 Nche EN et al. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(7):1359-1365.

___________________________

Dr. Scholle is a retina specialist and assistant professor of ophthalmology and Dr. Chancellor is a retina fellow. Both are at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Dr. Naguib is a retina fellow at New York University and Dr. Matharu is a cornea and refractive fellow at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Financial disclosures: None.