Download PDF

Every six months or so, Ronald W. Pelton, MD, PhD, sees a patient who sets off a particular alarm in his mind. “Often, I will see obvious physical signs of facial trauma, such as bruises or a broken nose—and falling in the tub or walking into a door frame won’t do that kind of damage.” At other times, the signs may be less obvious, “but I can just tell that something’s wrong,” he said.

Whether the evidence of intimate partner violence (IPV) is overt or covert, Dr. Pelton will ask questions about what’s going on in the patient’s life. But that opens the door to another dilemma: If patients confide that they are being abused by their partner, what comes next? In Colorado, where Dr. Pelton practices, there is no mandatory reporting requirement for episodes of IPV. Thus, if an abused patient doesn’t want to take the next step, once Dr. Pelton has treated any eye injuries, all he can do is watch—and wait.

On Your Doorstep

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognize four categories of IPV: physical violence, sexual violence, threat of physical or sexual violence, and psychological or emotional abuse.1

Prevalence and severity. In the United States, nearly 31 percent of women and 26 percent of men report experiencing some form of IPV during their lifetime.2 Women typically experience more severe forms of IPV than men.

Impact on children. Children living in households with IPV are at increased risk of being abused, emphasized Peter F. Cronholm, MD, MSCE, and Angelo P. Giardino, MD, PhD. Indeed, in its guidelines on IPV screening, the American Academy of Pediatrics states: “Intervening on behalf of battered women is an active form of child abuse prevention.”3

Common ophthalmic injuries. Ophthalmologists may be called to treat orbital fractures, globe ruptures, hyphemas, and retinal tears and hemorrhages, Dr. Pelton said. In addition (particularly if they are pediatric subspecialists), ophthalmologists may find themselves making the diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome, also known as abusive head trauma.

Use Your Radar

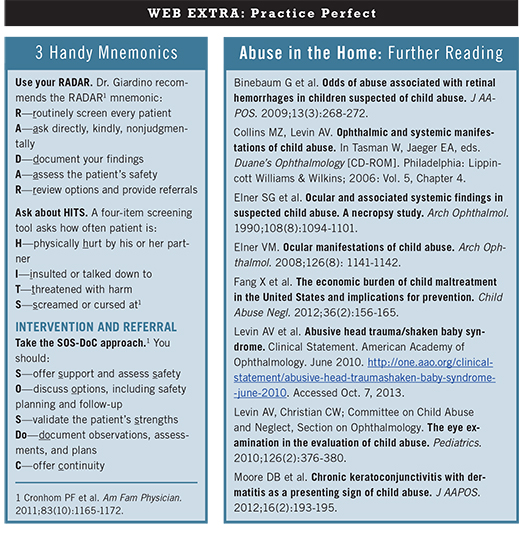

Dr. Giardino recommends the RADAR1 mnemonic:

R—routinely screen every patient

A—ask directly, kindly, nonjudgmentally

D—document your findings

A—assess the patient’s safety

R—review options and provide referrals

___________________________

1 Cronhom PF et al. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(10):1165-1172.

|

Is It Safe to Go Home?

“In some ways, physicians have been afraid to ask about IPV,” said Dr. Cronholm. “There’s a misplaced fear of the potential to do harm.” Essentially, the concern has been that the act of encouraging a patient to seek safety has the potential to escalate the cycle of violence. “But if you approach the issue from the perspective of increasing patient safety, the data from domestic violence screening show that there isn’t harm in asking,” he said. As a result of this and emerging data on IPV-related interventions, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force now recommends that clinicians screen for IPV—and that they either refer patients to or provide appropriate intervention services.2

How to raise the question of abuse. Primary care specialists are now expected to routinely screen for IPV, said Dr. Giardino. “It can be a little more complicated in surgical specialties, in that patients usually are seeking treatment for a specific issue and may wonder why the physician is asking about IPV. But for ophthalmologists, having a differential diagnosis that includes inflicted harm would be a reasonable approach.”

Screening can help build awareness. “A focused, directed screening process is appropriate, if it’s done in a caring manner,” said Dr. Giardino. “And it will achieve one of two things: First, if the person is being harmed, he or she may answer accurately, and you can make a referral to the appropriate agency. If that’s not the case, and the person is not quite ready to answer, your questions will start to build awareness in that patient’s mind that she doesn’t have to put up with this—and that someone is interested in helping.”

Specialists should be involved in screening. It’s important for ophthalmologists to not delegate this process to primary care specialists, Dr. Cronholm said. The timing may be right for the patient to confide in you, or “you may be on call and get an emergency referral,” he said. “With some fundamental, commonsense approaches, you can be helpful. It’s most important to be nonjudgmental, to validate their experience, and to reassure patients that it’s not their fault. At a minimum, ask ‘Is it safe to go home?’”

(click to expand)

Referral Tips

If a patient confides that he or she is being abused, what comes next? The process of guiding a patient toward the appropriate resources doesn’t need to be overwhelming for the physician, Dr. Cronholm said. “Much of the onus isn’t on the MD. Hopefully, you can bring in care managers and nurses; you’re part of a medical neighborhood. It takes a team approach.”

Resources in your area. Dr. Giardino agreed, noting that “not everyone has to be an expert.” He added, “If you have the luxury of practicing in the hospital setting, you will have a lot of support through the hospital’s social services department.” Outside of that setting, most counties and metropolitan areas have IPV resources, he noted. “Look first to the people in the women’s health arena.”

Resources online. Drs. Giardino and Cronholm recommended the Institute for Safe Families (www.instituteforsafefamilies.org) and Futures Without Violence (www.futureswithoutviolence.org) for their comprehensive lists of resources.

For the patient’s safety, handouts should be discreet. “Usually, a violent partner will be conducting some kind of monitoring or surveillance of the abused person, so you don’t want to give a patient an 8-by-10 folder that screams ‘Domestic Violence,’” said Dr. Giardino.

Legal Tips

In cases of child abuse, almost all states mandate that you report your findings. But the question of whether or not a physician must report a case of IPV is less clear-cut.

“It’s important to know your state laws,” Dr. Cronholm said. Some states and municipalities mandate reporting all cases of IPV, but this is relatively uncommon. Reporting requirements change in cases of criminal behavior, especially if weapons are involved, he said. “This is one instance in which providers are in a mandated role” in most states and must make a report.

Dr. Cronholm added, “Physicians should know that, in some states, their documentation of what the patient says is an exception to the hearsay laws and thus can be admitted as evidence. A physician should write down the specifics and take pictures of injuries as part of the clinical note taking; it’s all potentially part of the evidence.”

Dr. Giardino acknowledged that mandatory reporting is a controversial issue. “Some physicians are concerned that it makes patients reticent to volunteer information; others feel that it is the best way to promote screening. It still comes back to the discussion between the patient and the physician—and, in any case, making those referrals is essential.”

Honor Thy Patient

Dr. Pelton noted that the Academy Code of Ethics (www.aao.org/ethics) does not deal directly with IPV. However, the issue falls under the umbrella of patient confidentiality, he said. “If a patient admits to spousal abuse or violence, according to our code, we have to respect their wishes on how to handle it.” Of course, local and state laws must be taken into account, he added.

He has wrestled with this dilemma himself in treating patients who have experienced IPV. Several years ago, a patient of his was murdered by her husband. “I see her face very clearly to this day. One Tuesday, I’m talking to her in my office about her abuse; less than a week later, she’s the headline in the local newspaper,” he said.

In grappling with the complexity of IPV, physicians sometimes fall back on the position of “I don’t know what to do,” Dr. Pelton said. “But there are things you can do. In the aftermath of that tragedy, my wife and I got involved with a women’s shelter here in town. We’ve been involved with fundraisers, and I provide ophthalmic care on a pro bono basis. There are always ways to contribute.”

___________________________

1 www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pub/IPV_factsheet.html. Accessed Sept. 17, 2013.

2 Moyer VA; on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(6):478-486.

3 Thackeray JD et al. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):1094-1100.

___________________________

Peter F. Cronholm, MD, MSCE, is assistant professor of family medicine and community health at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Financial disclosure: None.

Angelo P. Giardino, MD, PhD, is vice president and chief medical officer of the Texas Children’s Health Plan and section chief of academic general pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Financial disclosure: None.

Ronald W. Pelton, MD, PhD, is an oculofacial reconstructive surgeon in Colorado Springs, Colo. He also is a member of the Academy Ethics Committee. Financial disclosure: None.