This article is from June 2012 and may contain outdated material.

What’s the best way to treat acute corneal hydrops? Given that most cases of hydrops—corneal edema resulting from tears in the Descemet membrane—eventually resolve spontaneously, many ophthalmologists rely on conservative management for this relatively uncommon condition associated with keratoconus, keratoglobus, and pellucid marginal corneal degeneration (PMCD).

More recently, however, a growing number of cornea specialists havebeen turning to a treatment approach that promises quicker resolution of the edema but may carry additional risks.

A Shift in the Paradigm

Conventional treatment of hydrops includes topical antibiotics, cycloplegics, and hypertonic saline as well as patching and bandage soft contact lens. When treated conservatively, the edema tends to resolve over two to four months, with some patients achieving acceptable visual results and others requiring subsequent surgery.1

The rethinking of hydrops treatment grew out of an observation taken from cataract surgery: When the Descemet membrane is detached after surgery, ophthalmologists have been using intracameral injections of air to reattach the membrane to the corneal stroma. In hydrops, there is a break in the Descemet membrane that allows aqueous humor to enter the stroma. Could an injected air bubble act as a tamponade to prevent aqueous humor penetration into the stroma?

This possibility prompted researchers to try using intracameral air to treat hydrops.2 That approach was followed, in turn, by the use of intracameral injections of sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) gas and perfluoropropane (C3F8) gas, which also act as mechanical barriers and prevent the entry of aqueous into the corneal stroma, but their resorption is much slower than that of air. These gases have long been used as a treatment for retinal detachment.

Research Overview

Intracameral air. In 2002, Miyata et al. published a retrospective study of intracameral air injections to treat hydrops secondary to keratoconus.2 Of 30 eyes with acute hydrops, 21 were treated with either no therapy or standard conservative management, while nine received 0.1-mL injections of filtered air.

The results: Corneal edema persisted for an average of 20 days in those who received the injections versus an average of 64.7 days in the control group. Similarly, patients who received the air injections were able to begin wearing hard contact lenses an average of 33.4 days after the onset of hydrops, while those in the control group had to wait an average of 128.9 days. BCVA after the hydrops subsided was similar between the two groups, and the injections induced no complications.

Intracameral SF6 gas. In 2007, Panda et al. reported results with the use of intracameral SF6 gas in nine eyes with acute hydrops secondary to keratoconus. Another nine eyes were treated conservatively.3

The results: Edema in the eyes that had received the injections resolved at four weeks versus 12 weeks in those treated conservatively. In addition, the mean BCVA at 12 weeks was slightly better in the eyes treated with SF6.

Intracameral C3F8 gas. Last year, a retrospective study of intracameral injections of C3F8 in eyes with hydrops secondary to keratoconus, PMCD, and keratoglobus was published in Ophthalmology. The study group consisted of 62 eyes of 57 patients; the control group included 90 eyes of 82 patients who were treated conservatively.4

The results: Edema resolved more quickly in eyes treated with C3F8 than in those managed conservatively. This effect was most evident in eyes with keratoconus; the time to resolution averaged 57.2 days in eyes treated with C3F8 versus an average of 104 days in the control group. Although edema also resolved more quickly in patients who had PMCD or keratoglobus and who had been treated with C3F8 than in the controls, the advantage was not as marked, possibly because of the position or size of the tear in the membrane, the researchers noted.

Final BCVA was roughly the same in the treatment and control groups, with a higher proportion of the C3F8-treated eyes with keratoconus achieving 20/40 vision or better.

|

|

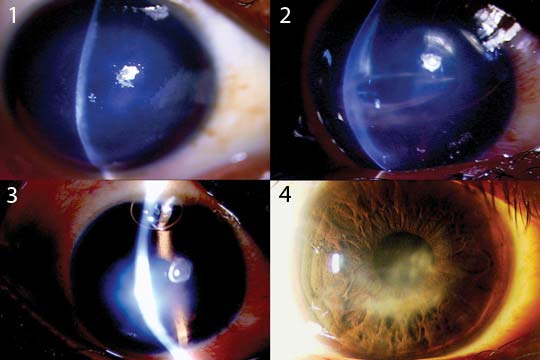

KERATOCONUS WITH ACUTE HYDROPS. (1) Three days after onset of symptoms. (2) One day after intracameral C3F8 injection, the gas bubble covers the break in the Descemet membrane. (3) One month after injection. (4) Seventy days after injection, edema has resolved, and visual acuity is 20/40 with contact lenses.

|

Real-World Concerns

“At the moment, I am not a big fan of using air or the retinal gases; I tend to be a little more conservative in managing hydrops,” said Michael B. Raizman, MD, codirector of the cornea and cataract service at New England Eye Center in Boston. However, he knows cornea specialists who routinely perform such intracameral injections, “so it definitely has been accepted by some,” Dr. Raizman noted.

For clinicians who are considering following suit, two experts who perform the injections offer several points to consider.

Timing of intervention. If you choose to do intracameral injections, how soon should you proceed? “You want to jump in early,” said William B. Trattler, MD, a cornea specialist with the Center for Excellence in Eye Care in Miami. “The goal is to get the Descemet membrane back into position flush against the back surface of the cornea so that it can heal. The gas works to block fluid entry into the cornea, which results in reduced corneal swelling. The sooner you can initiate the treatment, the quicker the recovery.”

Choice of gas. Which option is best—air, SF6, or C3F8? “My recommendation is to use one of the retinal gases, as they last longer in the eye than air,” Dr. Trattler said. Pravin K. Vaddavalli, MD, a cornea specialist with the LV Prasad Eye Institute in Hyderabad, India, agreed. “The thought process behind injecting an intracameral gas bubble is to have it present in the anterior chamber for a longer duration, leading to a sustained tamponade of the torn edges of the Descemet membrane. An air bubble wouldn’t suffice, as it would get absorbed too quickly. Both C3F8 and SF6 are good options.”

Choice of concentration. “C3F8 and SF6 should be used in isoexpansile concentrations to prevent further expansion of the bubble after surgery,” said Dr. Vaddavalli, a coauthor of the 2011 Ophthalmology study. “For C3F8, this would be a concentration of 14 percent; for SF6, it would be 18 percent.” Dr. Trattler proceeds on a case-by-case basis, using concentrations ranging from 16 to 18 percent.

Choice of setting. Dr. Vaddavalli recommended performing intracameral injections in the OR: “As the procedure involves a peripheral iridotomy and intracameral tamponade with frequent changes in the depth of the anterior chamber, peribulbar anesthesia in the OR would be ideal.” However, he added, “a topical procedure could be tried with intracameral anesthesia.” In contrast, Dr. Trattler performs the injections at the slit lamp.

Anterior chamber fill. “You want to do a 70 percent fill to avoid pupillary block,” Dr. Trattler said. As Dr. Vaddavalli noted, a complete anterior chamber fill followed by saline exchange, as is performed in Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK), is not advisable. “The principle behind a gas bubble to tamponade the torn edges of the Descemet membrane is different from that in DSEK surgery, which requires only a short period of contact of the Descemet graft with the posterior stroma to adhere,” Dr. Vaddavalli said. “Following hydrops, it would be desirable to have a constant-sized bubble in the anterior chamber to tamponade the curled edges of the membrane. Moreover, an air-gas exchange or an air-fluid exchange could have the potential of changing the isoexpansile nature of the gas bubble, potentially reducing its efficacy.”

Question of risks. Potential risks associated with intracameral injections include the following:

- Cataracts. Dr. Raizman noted that his primary concern with intracameral injections is that the introduction of air or gas into the anterior chamber could cause cataracts. “Cataracts have been reported after air in the anterior chamber with DSEK in phakic patients. These tend to be young patients who otherwise would not need cataract surgery.” The air or gas is left in place even longer with hydrops. Anterior subcapsular cataracts are a potential concern, Dr. Vaddavalli agreed, “as most of the patients are young.” He added, “The risk of developing an anterior subcapsular cataract was not evaluated in our paper but may be minimized by using miotics to constrict the pupil during surgery. However, reduced pupil size can increase the risk of a pupillary block, and this can be surmounted by performing an intraoperative peripheral iridectomy.”

- Endothelial cell loss. “This has been reported with both air and perfluoropropane in the anterior chamber in a rabbit model,” Dr. Vaddavalli said. “However, we believe the mechanical tamponade afforded by the gas bubble in the anterior chamber reduces the endothelial redistribution over the torn and detached Descemet membrane, eventually minimizing endothelial migration and resulting in lesser endothelial cell loss compared with eyes where no intervention is performed.” And Dr. Trattler noted that he has experienced no issues with endothelial cell loss.

- Pupillary block. There is an immediate postoperative risk of pupillary block, said Dr. Vaddavalli. “This can be avoided to a certain extent by titrating the amount of gas injected intracamerally and making sure the concentration of the gas-air mixture is in the right proportion to avoid postop expansion of the bubble.”

Question of compliance. Theoretically, patients should remain supine for two weeks after receiving intracameral gas injections. “It’s not necessarily for weeks; it’s more like a couple of days to a week,” said Dr. Trattler. “Still, patients aren’t always compliant, and you some- times have to make a point of urging them to keep their proper head position to maximize the effect of the gas.”

Looking Forward

What are the odds that intracameral injections will become standard practice? “None of the measures used in standard medical management have any clear indication or benefit,” argued Dr. Vaddavalli. “A surgical intervention to hasten the resolution of hydrops seems the natural course of action, as it is the only proven technique to reduce the time taken for the hydrops to resolve.”

But to settle the issue and, especially, to define the extent of cataract development and other risks, Dr. Raizman noted, “We need a prospective clinical trial, and that will be hard to do for such a rare condition.” Indeed, Dr. Vaddavalli and his coauthors estimate that a prospective trial to validate the efficacy of C3F8would require 63 patients in both the study and control groups for statistical power of 80 percent; for 90 percent power, the number of patients jumps to 85. In the meantime, Dr. Raizman said, “I still advocate conservative management. I realize that it’s frustrating for patients to have blurry vision for a couple of months, but that’s still the approach I use.”

But even before a clinical trial could be put together, it’s entirely possible that current corneal research could take the debate over treatment of hydrops in a completely different direction, Dr. Raizman said. “My hope is that, with collagen cross-linking and other techniques, we’ll be able to strengthen and reshape the cornea; and then hydrops could become a thing of the past.”

___________________________

1 Grewal S et al. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1999;97:187-198.

2 Miyata K et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(6):750-752.

3 Panda A et al. Cornea. 2007;26(9):1067-1069.

4 Basu S et al. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(5):934-939.

___________________________

Drs. Raizman, Trattler, and Vaddavalli report no related financial interests.