Download PDF

From the narrowing of networks to an increasing emphasis on value-based payments—how has the ACA affected eye care?

Three primary goals of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 were to expand comprehensive health coverage to the uninsured, improve quality, and decrease costs.1

“The ACA addressed significant abuses,” said George A. Williams, MD, the Academy Secretary for Federal Affairs, who chairs the ophthalmology department at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in Royal Oak, Mich. “These included exclusions for preexisting conditions and other discrimination based on health status, as well as lifetime limits on coverage. We have good evidence that approximately 11 million Americans have been added to the insurance rolls since the inception of the ACA, and by those criteria, we’ve had some success.”

“But if the real question is how many have insurance they can really use, the answer may be a little different,” added David B. Glasser, MD, chair of the Academy Health Policy Committee and assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Does it make it more accessible to the patient, or is it coverage in name only?” When these questions are combined with concerns about cost and quality control, most might agree that the ACA is still a work in progress.

How have ophthalmologists and their patients fared thus far? Four experts provide some insights.

How ACA Affects Ophthalmology

For better or worse, the ACA has influenced the health care landscape in many ways—including greater coverage, higher cost sharing, narrow networks, value-based purchasing, new payment models—and many ophthalmologists have wondered how their professional lives, and the health of their patients, might change as a result.

Although new insurance plans under ACA may bring access to more patients, said Dr. Glasser, some ophthalmologists have expressed concerns about a profusion of proverbial hoops to jump through, as well as reimbursement challenges, to name just two problems.

Impact on ophthalmology has been relatively limited so far. A large proportion of ophthalmology patients are on Medicare, said Michael X. Repka, MD, Academy Medical Director for Governmental Affairs and professor at Johns Hopkins University. “So we are somewhat protected from the impacts of ACA.” In addition, he said, eye care is not hospital based, nor does it constitute a huge portion of commercial insurance portfolios. Considering that those entities are dealing with big-ticket items, such as heart disease or diabetes, ophthalmology is not one of their priorities—at least not yet.

Vertical integration of health care around health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and hospitals predated ACA, said William L. Rich III, MD, Academy Medical Director for Health Policy, who practices at Northern Virginia Ophthalmology Associates in Washington, D.C., but the trend was encouraged by ACA. “That gave hospitals tremendous financial stimuli to buy physician practices,” he said. “But ophthalmologists generate the lowest percentage of revenue per year with hospitals, so these institutions have little incentive to hire them.”

Other influences beyond ACA. It’s true that the ACA has accelerated or adjusted a few trends that do affect ophthalmology, such as narrow networks and quality reporting, said Dr. Repka. “But some physicians blame ACA for many things it’s not responsible for, such as electronic health record (EHR) requirements and ICD10.” And while the ACA expanded the use of value-based purchasing, ophthalmologists were already subject to programs like the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), used by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to evaluate the quality of physician services under Medicare, he said.

|

|

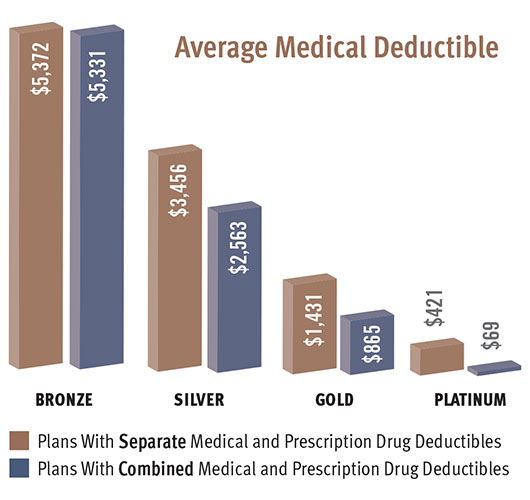

STICKER SHOCK. Patients who opted for plans with cheaper premiums are frequently stunned by the size of the deductibles. “We’re encountering patients who believe they have insurance but don’t realize they have a significant copay,” said Dr. Williams. “They sign up for a plan, pay their premiums, walk into a doctor’s office with an acute problem like a retinal detachment, and are told they’re responsible for the first $6,000.”

|

Impact of Cost Sharing

Today, there are patients covered by some type of insurance—whether Medicaid or commercial plans on the exchanges—who might have been charity cases before, said Dr. Rich.

There was also a significant number of people shopping for new insurance on the exchanges because their previous insurance was not compatible with the ACA mandates. “There’s no question that their new coverage is better,” said Dr. Williams. “But is the price worth the better coverage? One side of the aisle will say yes, the other side no.”

Insurance companies strive to keep their costs down. As ACA brings more people on board, insurance companies have looked for ways to cut costs. “They basically have two levers they can move—increase premiums or increase deductibles and copays,” said Dr. Williams. “To make the pricing politically palatable, the structure of the ACA allows for very high deductibles. It permits insurance companies to structure plans with deductibles as high as $6,500 for an individual and $12,700 for a family.”

Although the exchanges offer four levels of coverage, said Dr. Repka, many patients have gone for lower premiums, choosing silver or bronze. Bronze plans, in particular, have high deductibles, said Dr. Rich, “and we are just starting to see the impacts on chronic care with these massive outlays out of pocket.”

Patients experience sticker shock. Many patients who are new to these plans, such as those previously on Medicaid or covered through an employer, have been surprised by the high deductibles, said Dr. Repka. It’s not only a shock for the patient, he said, but also creates a difficult situation for the ophthalmologist who has to explain, “Yes, you have medical insurance, but no, it won’t cover what you need here without a substantial out-of-pocket expense.”

The physician-patient relationship is further stressed because physicians are increasingly responsible for collecting larger amounts directly from patients, as opposed to being paid by a third-party payer, said Dr. Glasser.

And how much trouble do these larger payments cause? According to the Federal Reserve’s most recent report on the economic well-being of U.S. households, only 48 percent of Americans would be able to completely cover an emergency expense costing $400 without selling something or borrowing money.

Insureds’ changing behaviors. A major concern with high-deductible health plans is that the costs may discourage patients from seeking the care they need to help manage a condition so that it doesn’t progress to crisis stage, said Dr. Glasser. “High-deductible plans may cause patients to skip ‘routine’ checkups, which in reality are important for detection and management of diseases such as glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration,” he said. “We’ve managed to reduce blindness from AMD by 90 percent since the introduction of anti-VEGF agents for patients who are appropriately followed. But if follow-ups are too costly for patients, they won’t access that benefit.”

In addition, Dr. Williams has seen more individuals declining elective surgeries or putting them off until the last quarter of the year when they’ve fulfilled their deductible.

What’s next? Other cost questions remain: Will premiums also go up significantly? What about more changes in drug formularies?

“There are $12 generics that have gone up to $100,” said Dr. Glasser, “and glaucoma medications with copays that have gone from $5 for a generic up to $50. Patients are being asked to switch medicines and pay more out of pocket. Some of these changes may be related to the ACA and the need for third-party payers to save money. Others may be related to the huge price run-up in generics. It’s difficult to sort out how much to attribute to ACA.” (For more on the pricing of generics, see “The State of Generic Drugs” in the January 2015 EyeNet.)

|

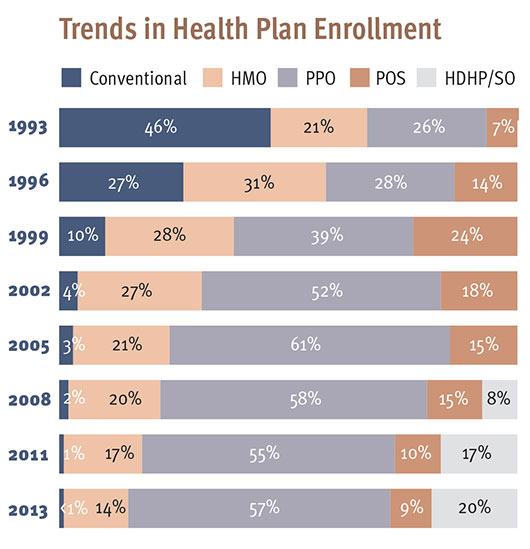

THE RISE OF THE HIGH-DEDUCTIBLE PLAN. The trend toward high-deductible plans predates the ACA, according to Kaiser surveys of nonfederal private and public employers. Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred provider organization; POS, point of service; HDHP/SO, high-deductible plan with a savings option. Conventional plans are indemnity plans—the traditional fee-for-service plans.

SOURCE: Kaiser/HRET survey of Employer-Sponsored Health benefits, 1999-2013.

|

Impact of Narrower Networks

Another cost-cutting effort by insurance companies is to limit access to physicians they consider high cost. In narrow networks, some providers may take a lower payment in exchange for seeing more patients, said Dr. Repka, whereas other providers, who are more expensive, will have increasingly difficult access to patients in these networks.

“With ACA,” said Dr. Glasser, “there were predictions that payers would be selective in the hospitals they used, have more restrictive formularies, require more preauthorizations, and contract with lower-cost providers. We anticipated problems but weren’t prepared for the suddenness with which this all hit.”

Networks based on incomplete data. Insurance companies have accumulated data to determine which providers are most expensive. “Narrow network is a tool that has allowed them to price their insurance products less expensively,” said Dr. Repka. “The problem is, the data about physicians may be very accurate on price, but not very helpful when it comes to analyzing quality outcomes.”

Comparing apples with oranges. In addition, this system lumps together all ophthalmologists. “Many subspecialists would either appear to not meet quality measures because data are lacking about what they do,” said Dr. Repka, “or they have a few expensive patients, which makes them look like price outliers.”

Retina specialists are a prime example, said Dr. Williams. “If you look at their utilization of resources, they appear as high-cost providers because they use very expensive drugs that are necessary for certain diseases such as AMD or diabetes. Therefore, they are at greater risk of being dropped from plans.”

Inappropriate exclusion and tiering. “Physicians taking care of the sickest patients are either excluded from their own networks,” said Dr. Rich, “or they’re tiered so the patient with a higher copay has a marked financial incentive to not see the doctor who can deliver the highest level of care for more advanced disease.” Some exclusions may be justified, he added, but this “blunt instrument” disproportionately affects subspecialists.

This has left some physicians with fewer patients, said Dr. Glasser, and in many cases, patients lack access to the specialist care they need—sometimes forcing them to drive a long way or wait a long time to see a doctor. It has also become very disruptive to the physician-patient relationship, added Dr. Williams.

How to respond. It’s important to monitor how the insurance company is tiering you and how your patients are affected by it, advised Dr. Repka. “It’s worth calling provider relations.” In some cases, added Dr. Glasser, specialists who’ve been dropped have been reinstated, but the results have been somewhat variable.

“The glaucoma specialists responded,” he said, “by developing a set of severity codes for glaucoma, which will appear in ICD-10. They are hoping this will help insurance companies differentiate care between the less and more complex patients and prevent unfair profiling.”

In addition, said Dr. Williams, the Academy remains involved with Congress and regulators to ensure that plans provide adequate access to specialty physicians—whether ophthalmologists or other specialists. “There’s broad support for this throughout medicine,” he said.

Impact of Value-Based Purchasing

Value-based payment modifiers (VBM) are a cost-control mechanism put in place by CMS to measure physicians in two domains, quality and cost. Required by ACA, they are applied to all Medicare physicians’ fee-for-service claims starting in 2015, said Dr. Williams. “Some of this predated ACA, but it’s part of what I call the ACA mindset at CMS: to pay physicians based on performance criteria as CMS chooses to define them.”

VBM penalties pay for VBM bonuses. This system, which is budget neutral, involves a two-step process with the potential for bonuses and penalties, said Dr. Glasser. “The bonus pool is funded by dollars that are assessed by penalties. So bigger penalties equal bigger bonuses. This year, groups of 100 or more physicians are subject to penalties or bonuses. In 2016, it will be groups of 10 or more; and in 2017, it will impact all providers.”

PQRS. The first step is based on PQRS success. “If you don’t clear the PQRS hurdle, you get a 1.5 or 2 percent PQRS penalty. In 2015, it’s 1.5 percent, based on what you did in 2013. In 2016 and going forward, it’s a 2 percent penalty on what you achieved two years previously,” said Dr. Glasser.

“The PQRS program has been around for a while,” said Dr. Williams, “but it’s become much more onerous, requiring completion of an increased number of measures. The easiest way to successfully qualify and not be penalized is to participate in a qualified clinical data registry. In ophthalmology, the only one available is the IRIS Registry,” he said. (At time of press, the IRIS Registry had successfully been integrated with 26 different types of EHR. If you don’t have EHR, you can report PQRS via the IRIS Registry Web portal. Learn more at www.aao.org/irisregistry.)

VBM tiering. If you report successfully on PQRS, said Dr. Glasser, you avoid PQRS-related penalties, and then you go into the second step—a tiering competition that awards bonuses and assesses penalties based on cost and quality. “It, too, uses two-year-old data with high-cost, low-quality providers receiving the maximum penalty and low-cost, high-quality providers receiving the maximum bonus.”

“This again will have a varying impact on ophthalmologists,” said Dr. Williams. “Anyone who uses branded anti-VEGF agents, for example, will be identified as a high-cost provider and, therefore, face potential penalties.”

Pending legislation may expand use of VBM. In late March, a bill was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives that would eliminate Medicare’s flawed Sustainable Growth Rate formula while, starting in 2019, also doubling down on VBM. At time of press (early April), the Senate hadn’t indicated whether it would endorse, modify, or reject the House bill.

Ophthalmology: A Minor Role for ACOs?

There has been a proliferation of ACOs on both the Medicare and commercial sides, with well over 600 in existence, said Dr. Repka. “The commercial ACOs are focusing mainly on outpatient care and behavior modification,” he said, “while those in Medicare are largely focusing on inpatient care, or reducing the number of days in the hospital.”

What’s the impact? Although ACO penetration is regional, said Dr. Williams, they have limited impact on ophthalmologists overall. Because ophthalmology doesn’t cost a lot and isn’t hospital based, added Dr. Repka, ACOs are not putting their emphasis here. “They may get around to it,” he said. “There are clearly places in drug formulary they will look at in the future, but to the best of our knowledge we’re not there yet.”

“The reality is, unless you’re employed by Kaiser or a hospital that’s in an ACO, it has no impact on your fees,” said Dr. Rich. “You still get paid directly fee-for-service Medicare.”

What to do. “If you do choose to participate,” said Dr. Williams, “the Academy advises you not to sign any exclusive contracts that limit your participation to a single ACO.” However, even if you don’t participate, consider that the ACO may be looking for ophthalmologists in its area who can deliver the most cost-effective care, said Dr. Glasser. “You may see fewer referrals from ACO primary care physicians if you’re not providing care the ACO considers cost-efficient.”

|

Testing New Payment Models

Through the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, the government has invested more than $11 billion to explore novel payment methods such as medical homes, accountable care organizations (ACOs), and bundling of care, said Dr. Rich. “Unfortunately, these payment models are poorly designed and failing.”

False starts. Similar to the diagnosis-related groups and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) of the past, said Dr. Glasser, ACOs and medical homes were supposed to save money by paying for episodes of care under one roof—holding the provider responsible for ensuring that patients get what they need in a cost-efficient manner.

“Medical homes, however, often do not achieve the goals of decreasing costs and emergency room visits,” said Dr. Rich. “Fewer primary care doctors and internists are participating than expected, apparently because they can make more money going into concierge medicine.”

With ACOs, the group assumes risk, said Dr. Glasser. “If they perform better than target, they have the potential for earning more. If they perform worse than target and the care costs more than expected, they are at financial risk.” This concept has also met with varied success, he said.

Few savings. Few savings have been reported with the Medicare ACOs, said Dr. Repka. “With more people involved, the commercial ACOs may show some promise, but we have limited data on their success.” Due to lack of financial rewards, about half the innovative ACOs have gotten out of pilot risk-sharing programs with the federal government, said Dr. Rich.

It remains to be seen whether CMS’ recently announced revisions to ACO regulations will help stem that receding tide by introducing more choice and flexibility.2

Practice patterns. Dr. Glasser noted that we have seen some changes in practice patterns—for example, the Kaiser system is considering bilateral same-day surgery or immediately sequential cataract surgery, and changes in anesthesia support in the OR—“but I’m not sure these changes relate to ACOs. They probably would have been coming anyway.”

Primary concerns. The biggest impact on medicine may have less to do with the ACA and more to do with a philosophical approach to payment, said Dr. Rich. Specifically, there seems to be a widespread belief that primary care doctors are underpaid and specialists overpaid. The need for primary care doctors is driving some of the payment policies in fee-forservice Medicare, shifting money from specialists to primary care, with dramatic impacts on minor office procedures and major surgeries, he said.

ACA Advocacy Priorities

Fee for service and Medicare Advantage will remain a focus of the Academy’s advocacy efforts, said Dr. Repka, simply because these are key to ophthalmology practices for the foreseeable future. But the commercial space must also be monitored to make sure narrowing networks don’t squeeze out access to patients.

Maintaining access is an overriding priority, agreed Dr. Williams. “We also want to assure fair and reasonable payment for our services, and to maintain control over the physician-patient relationship, ensuring that treatments aren’t dictated by insurance companies or the federal government. As problems develop, we’ll address them through our regulatory advocacy efforts.”

Dr. Glasser emphasized that the mantra of evidence-based medicine should be applied to regulation. “For example, before asking 100 percent of Medicare providers to report new PQRS measures, why not first do a pilot study to see if they actually improve outcomes? A lot of regulations get put into place by altruistic and enthusiastic congressional staffers, but what looks good on paper doesn’t always translate well to the exam room.”

To prevent destabilization of Medicare, added Dr. Rich, the Academy will need to advocate for prevention of cuts under PQRS and EHR meaningful use to physicians who are not in primary care, making clear to policymakers that the bar for reporting specialty quality measures is no longer feasible for practicing physicians who are not part of a large group.

For the latest advocacy news, go to www.aao.org/advocacy. For advocacy tips, see this month's Practice Perfect.

___________________________

1 U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Accessed March 23, 2015.

2 CMS Federal Register/Vol. 79, No. 235/Monday, December 8, 2014: Medicare Program; Medicare Shared Savings Program: Accountable Care Organizations. Accessed March 23, 2015.

|

The Future of the ACA

At this point, there are many unknowns.

Vulnerable financing. “If the Republicans can manage to get rid of either the mandate or the various taxes, it may make the financing look even less favorable than it did when the legislation passed,” said Dr. Repka. “We don’t expect any major overrides this year or next because of the veto threat. But what happens in 2017 is an open question.”

In the meantime, tax-credit subsidies for health plans purchased through federal exchanges have been challenged and will be reviewed by the Supreme Court, with a ruling expected in June. In King v. Burwell and the set of related lawsuits, the plaintiffs argue that the ACA only allows for subsidies on state-run exchanges. More than half of state exchanges, however, are currently run by the federal government. “There’s no question that a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs would be very disruptive and affect millions of people,” said Dr. Williams. “Many experts believe that if the Supreme Court rules federal exchanges invalid, the whole ACA structure will collapse.”

Down the road. If this fails to transpire, however, Dr. Rich doesn’t see major changes within three to five years, although he thinks hospitals may have more employee physicians and may hire more ophthalmologists.

“I think fee for service will still be here,” he said, “mainly because insurers, hospitals, and pharmaceuticals will never allow single payer to take root. In the U.S., the largest employers in 80 percent of counties are hospitals, and single payer is simply against their interests.”

Meet the Experts

DAVID B. GLASSER, MD Assistant professor of ophthalmology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore; managing partner, Patapsco Eye MDs in Columbia, Md.; Academy chair of the Health Policy Committee. Financial disclosure: None.

MICHAEL X. REPKA, MD, MBA David L. Guyton, MD and Feduniak Family Professor of Ophthalmology and Professor of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore; Academy Medical Director for Governmental Affairs. Financial disclosure: None.

WILLIAM L. RICH III, MD Senior partner at Northern Virginia Ophthalmology Associates in Washington, D.C.; Academy Medical Director for Health Policy. Financial disclosure: None.

GEORGE A. WILLIAMS, MD Professor and chair of ophthalmology, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in Royal Oak, Mich.; Academy Secretary for Federal Affairs. Financial disclosure: None.

|