This article is from July/August 2008 and may contain outdated material.

Physicians generally regard bold claims with an understandable mistrust. But every now and then a new treatment makes such a dramatic difference in patients’ lives that some genuine enthusiasm may be in order. That appears to be the case with the emerging use of amniotic membrane to alleviate the severe ocular manifestations of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).

Amniotic membrane has been used for some time in attempts to repair the damaged ocular surface after a bout of SJS. Only recently has it been applied during the onset of inflammation. The evidence thus far suggests that early treatment can mean the difference between preserving normal sight and surrendering to significant, permanent visual impairment.

Devastating Disease

“Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a horrible disease—the worst eye disease one can see. It’s like a burn in the eye,” said Scheffer C. G. Tseng, MD, PhD, who is in private practice in Miami. “In the past, no one did anything about the eyes in the acute phase. They were struggling to save the patient’s life. But by the time you saved the patient’s life, they were blind.”

Prosaic causes, catastrophic effects. SJS is often an allergic reaction to certain common drugs, particularly sulfonamides, penicillins and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories. Less frequently it can result from infections or malignancies.

The reaction presents with widespread exfoliation of the skin and mucous membranes, with clinical manifestations similar to those of partial-thickness burns. As a result, people who develop SJS are typically referred to burn units for treatment. In its most severe form—toxic epidermal necrolysis—the disease is frequently fatal.

Most SJS patients develop inflammation of the conjunctiva during the acute phase of the disease. When the inflammation is severe, it destroys the mucosa of the ocular surface and eyelids, leading to intractable dry eye, vision loss, severe chronic pain and photophobia.1

SJS also affects the lid margins and eyelashes, distorting eyelash structure and increasing the risk of corneal abrasions.

If the corneal limbal stem cells are destroyed, the cornea can be covered by the surrounding conjunctiva and become vascularized, reducing the chances for a successful corneal transplant if needed in the future.

|

|

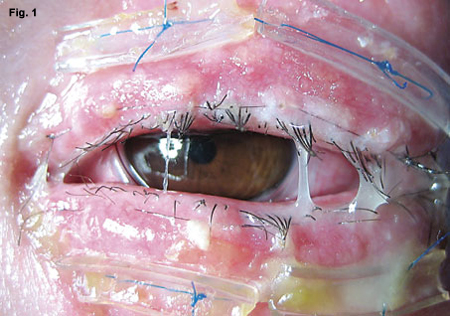

Taming the Terrible. Ten-day postop Stevens-Johnson patient treated by Dr. Gregory with amniotic membrane (Fig. 1). As the membranes degraded they appeared mucopurulent but were not infected. Four months later the patient was completely recovered, with no dry eye or other sequelae (Fig. 2).

|

Placentas to the Rescue

Amniotic membrane is the innermost of the membranes originating in the placenta. It contains a single layer of epithelial cells, a thick basement membrane and a stroma.

The basement membrane supports epithelial cell migration, adhesion and differentiation, and inhibits epithelial cell apoptosis. The stroma is avascular and rich in growth factors and protease inhibitors. Amniotic membrane exhibits strong anti-inflammatory properties, suppresses scar formation and reduces neovascularization of the eye.

Gary N. Foulks, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Louisville, coauthored the first paper on using cryopreserved amniotic membrane in the acute phase of SJS.2 “Amniotic membrane has been used in ophthalmology for a long time, but mostly in treating damage to the ocular surface after the acute disease has subsided,” said Dr. Foulks, who is also editor-in-chief of The Ocular Surface. “It was more of a reconstruction of the damaged surface. But it seems to work very well in the acute treatment of this problem.”

The “Stevens-Johnson guy.” By peer acclaim, Darren G. Gregory, MD, has treated more acute-phase SJS patients with amniotic membrane than anyone else in the United States. Dr. Gregory, an assistant professor of cornea and external disease at the University of Colorado in Denver, began seeing SJS patients several years ago. At the time, he was in charge of inpatient consultations at two university-affiliated hospitals in the Denver area, and because Denver has the only intensive care burn units within a 500 mile radius, SJS patients are transferred in from a very large region.

“I came to realize that the treatments we had for these patients weren’t working very well,” he said. “About two and a half years ago I was searching the literature trying to find something that would help them, and I found Thomas Johns and Gary Foulks’ 2002 article in Ophthalmology describing the use of amniotic membrane for this purpose.”

The first acute-phase patient Dr. Gregory treated with amniotic membrane died the next day from the systemic disease. But his next SJS patient did quite well with only moderately aggressive amniotic membrane treatment, he said, especially considering the severity of her disease. Dr. Gregory subsequently spread the word that the two burn centers in Denver should contact him immediately when they received an SJS patient, and he soon became known as “the Stevens-Johnson guy.” He has since used amniotic membrane successfully to treat many acute-phase SJS patients, all of whom have had good visual outcomes with minimal dry eye problems.

Treat during the window. Dr. Gregory noted that there appears to be a window of opportunity of about two or three weeks to prevent the ocular complications of SJS—but the goal is to treat people as early as possible. A typical scenario is that a patient sees a primary care physician for a skin rash, develops pain in the eyes and mouth within a day or two and is then hospitalized.

Some of Dr. Gregory’s patients have already spent five or six days in another hospital before being transferred to his institution. Because the literature provides little guidance for managing the ocular consequences of SJS, many of the transferred patients have received well-intentioned but not particularly beneficial ophthalmic care.

“I treat the patients as soon as I can, and to do that I’ve had the hospital stock the amniotic membrane on site,” Dr. Gregory said. “Our most recent patient was transferred to our facility three days into her episode, and we were doing surgery on her four hours after she arrived.”

How to Use the Membrane

The cryopreserved amniotic membrane product used to treat acute-phase SJS, Amniograft (Bio-Tissue), was developed by Dr. Tseng. Amniograft is supplied in sheets and can be shipped overnight in North America and thawed just prior to use.

Apply by sliding. Dr. Foulks noted that a general ophthalmic surgeon can successfully apply amniotic membrane to the ocular surface and lids. “The membrane is very thin and tends to wrap around itself, so when removing it from the paper it’s important to slide it onto the surface of the eye and not let it dangle in mid-air,” he said. “But once it’s on the eye, it’s usually very easily manipulated into position to either suture or glue in place.”

Suture for best effect. Dr. Foulks described the suture technique he uses: “Nylon suture on a fine needle can be used to secure the edge of the membrane to the lid margin and two larger silk sutures on large curved needles can be passed through the eyelid in mattress fashion to secure the membrane that is reflected into the fornix. If only the bulbar surface is covered, the fine nylon can be passed through the edge of the membrane and secured to peripheral conjunctiva. When fibrin glue is used to secure the membrane it is spread across the surface to be covered and the membrane quickly spread over the adhesive with a smooth muscle hook until the membrane is securely in place.”

Whenever possible, Dr. Gregory prefers to suture the membrane in the operating room under an operating microscope. His surgical techniques for applying amniotic membrane to the ocular surface and the eyelids are described in the April 2008 issue of The Ocular Surface.1 He believes that using stitches probably allows the membranes to stay in contact with the affected surfaces longer.

Amniotic membrane typically dissolves over a period of one or two weeks. Thus more than one application may be necessary during the acute phase of SJS.

A smaller but easier option. A new product called Prokera (Bio-Tissue), also developed by Dr. Tseng, can be inserted into the eye without sutures. Prokera consists of a polycarbonate ring set with amniotic membrane stretched across the lumen and clipped into place. The device is placed on the eye like a contact lens. Prokera does not provide as much coverage of the ocular surface as a sheet of amniotic membrane, but its ease of use makes it valuable for patients who are on ventilators or who cannot easily be taken to the OR.

Dr. Tseng noted that freeze-dried amniotic membrane is also available but is FDA-approved only as a dressing, not as a surgical graft. The freeze-dried membrane, however, is very easy to work with, according to Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University and codirector of the cornea service at Wills Eye Institute in Philadelphia. Dr. Rapuano has not used amniotic membrane for acute SJS, and his experience using it for chronic changes following an acute episode did not impress him. He has, however, obtained good results using the freeze-dried membrane for some other pathologies.

“You can cut it to the exact size and shape you want in its dry form, place it on the eye and then moisten it. It isn’t as sturdy as the Bio-Tissue frozen version, but works quite well for certain indications, such as chronic epithelial defects,” he said.

Paradigm Shift

Dr. Tseng has treated the largest series of SJS patients in the chronic phase of the disease, after their vision was already damaged. He has listened to countless stories from patients who woke up feeling fine on a particular day but had their lives changed forever when they developed SJS. He is passionate about preventing blindness with the early use of amniotic membrane. “Before we had nothing to offer these people, but now we have a very different outcome,” he said. “It’s a true success story, really a night-and-day type of impact. With amniotic membrane we have changed the paradigm of how we treat these patients.”

Share the news. Dr. Gregory wants to increase awareness of SJS among ophthalmologists and to get the word out on the sight-saving treatment option that is now available.

“It’s possible that an ophthalmologist might be on call at an emergency room or be contacted by a primary care physician who is caring for a Stevens-Johnson patient in the hospital,” he said. “Right now there are isolated case reports, but, on the whole, our field is not aware that this option exists. Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a devastating disease, but the ocular damage seems largely preventable with this membrane. If people aren’t comfortable in performing the procedure themselves, they should find someone who is.”

___________________________

1 Gregory, D. G. Ocul Surf 2008;6:40–48.

2 Johns, T. and Foulks G. N. et al. Ophthalmology 2002;109:351–360.

___________________________

Drs. Foulks, Gregory and Rapuano have no related financial interests. Dr. Tseng has proprietary interests in the products described in this article.

___________________________

Since the use of amniotic membrane for treating acute SJS is relatively new, EyeNet encourages readers to watch for broader peer-reviewed reports in the literature.