By Laura B. Kaufman, Contributing Writer

Interviewing Kathryn A. Colby, MD, PhD, Deborah S. Jacobs, MD, Ken K. Nischal, MD, Stephen C. Pflugfelder, MD, and Bibiana Reiser, MD

This article is from October 2012 and may contain outdated material.

When ophthalmologists think about dry eye patients, the image that most likely comes to mind is that of an individual, often a woman, who is middle aged or older. Symptoms of dry eye are one of the most common reasons that adults seek eye care; and, according to the Academy’s “Eye Health Statistics at a Glance,” nearly 5 million Americans over age 50 are estimated to have dry eye syndrome. Yet even though the condition is considerably rarer in children, cornea and pediatric eye specialists believe that it may be both underdiagnosed and undertreated in kids and teens.

Just as in adults, dry eye in children can be irritating and painful and, in severe cases, can affect vision. These symptoms can have a particularly strong impact on children’s lives by making it more difficult for them to perform school and study activities such as reading and using a computer.

The first step in reducing the impact of dry eye in children is developing a greater awareness of the condition and possible causes. Beyond that, several pediatric and cornea specialists provide their advice on overcoming diagnostic and management challenges in these young patients.

A Wide Range of Causes

The causes of dry eye in children can range from commonplace allergies to severe systemic conditions such as immune or neurologic disorders. Although it’s important to keep an open mind about possible etiologies, start by considering the most likely, the experts advise.

Evaporative eye disease. Ken K. Nischal, MD, a pediatric anterior segment specialist and chief of the Division of Pediatric Ophthalmology at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, said, “The first thing to know about dry eye in children is that the most common cause is evaporative eye disease, most frequently caused by meibomian gland dysfunction [MGD]—which is more common than is realized.”

Kathryn A. Colby, MD, PhD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and a cornea surgeon at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and Boston Children’s Hospital, agreed. “The vast majority of children with dry eye have evaporative dry eye, which is underappreciated.” She added that “in this type, the tear film is of lesser quality. Aqueous tear deficiency dry eye is not as common.” She also noted that many general ophthalmologists don’t recognize there are different types of dry eye.

Blepharitis. This inflammation of the eyelid margins is now classified as a form of MGD and may have an infectious or noninfectious source. It can affect the composition of the tear film and cause dry eye. In some cases, it is associated with rosacea or other skin conditions, especially in people of European descent.

Herpes simplex infections. According to Dr. Colby, “Herpes simplex virus is very common in children, and it’s good to keep it in the back of your mind. HSV can do anything it wants to in the eye and can cause cornea problems or inflammation on the eye’s surface.” For example, although it occurs more rarely in children than in adults, HSV keratitis can disrupt the innervation of the cornea, which impacts tear secretion and composition.

Medications. Bibiana Reiser, MD, director of the Cornea Institute at the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, said that physicians may inadvertently cause dry eye secondary to medications. One example is oral contraceptives in teen girls. “You may not even think of it, but these drugs are frequently prescribed to treat skin problems and dysmenorrhea. Some [ocular] symptoms can mimic what you see in menopausal women.”

|

|

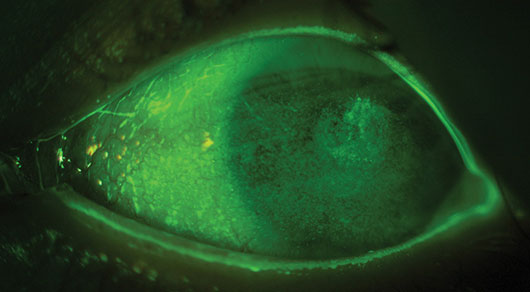

A CONGENITAL CASE. Fluorescein staining confirms dry eye syndrome in an 8-year-old boy with Goldenhar syndrome and congenital corneal anesthesia.

|

More Ominous Etiologies

However, even though dry eye in kids most commonly results from evaporative disorders, Dr. Reiser warned ophthalmologists to rule out a possible “constitutional cause.” She said, “In children, dry eye may not be just dry eye; it could be something worse. If it does not resolve on its own, be leery about treating a child like an adult, and be quick to refer. There may be an undiagnosed inflammatory or infectious cause that can affect their vision permanently. Because kids tend to do well, we tend to underdiagnose.”

Stephen C. Pflugfelder, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine, said, “Eye M.D.s who see children with symptoms of dry eye should also consider systemic or neurological conditions. Severe symptoms that bring kids to me include photophobia or squinting, indicating sensitivity to bright light, or a child who never sheds tears or has stopped shedding tears when crying. These should be warning signs,” pointing to an underlying problem.

Graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD). For example, children who receive allogeneic bone marrow or stem cell transplants for leukemia or genetic conditions often develop GVHD resulting from an immune response to the “foreign” cells. Ocular structures are affected in approximately 80 percent of GVHD patients. The sites most commonly involved are the ocular surface and lacrimal glands, leading to painful dry eye.1

Neurologic disorders. In addition, neurological conditions—either a malfunction of the nervous system or a genetic disease such as Riley-Day syndrome—can be associated with alacrima and severe dry eye. “They are seen at big medical centers along with other systemic issues, such as orthostatic hypotension. We see two to five cases per year; a typical practice might not see one,” Dr. Pflugfelder said.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome. He has also observed that “there seems to be an increase in prevalence of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a severe immune reaction to a medication, causing blistering of the mucous membrane of the eye, which can be very serious.” Among the drugs that may trigger this syndrome are ibuprofen and sulfa drugs such as Bactrim, he said.

Diagnosing Dry Eye in Children

Children may come in complaining of an uncomfortable foreign body or burning sensation, and parents may notice eye rubbing or redness. Youngsters who wear contact lenses may complain about chronic discomfort. These clues should alert the clinician to evaluate for dry eye.

Challenges—and solutions—in diagnosing children. One reason for the underdiagnosis of dry eye, said Dr. Colby, is that children can be so challenging to examine. “The vast majority of affected children are over age 7 and are able to express their symptoms. But often, they are not cooperative with a detailed slit-lamp exam. I’ve learned that, when managing corneal problems in children, you do as much as you can at each exam; and if it is not enough, then you have the patient come back and try again on another day when they may be more cooperative.” She added that, for severe conditions, an examination under anesthesia may occasionally be necessary if it’s not possible to see what you need to see during an office visit.

Another difficulty, said Dr. Nischal, is that “you cannot diagnose dry eye with the Schirmer’s test in children because the moment you put something in the lid, they start to blink and want to rub or scratch, which causes reflex tearing. Diagnosis entails investigating tear meniscus height, epithelial erosion, and tear breakup time—which is longer in children than adults. If it’s under 20 seconds, the child probably has dry eye. For children under age 12, it could be over 25 seconds.”

Dr. Colby noted that it is easy to miss evaporative dry eye if you don’t look for it. She recommends checking tear breakup time as the easiest way to evaluate tear quality.

Look at the patient—and the family. Dr. Reiser suggested that ophthalmologists look closely at the skin and lid margins. “Is it inflamed? It could suggest blepharitis or rosacea.” In addition, Dr. Colby said, “Look at the parents, as children usually come in with parents or siblings, for underlying facial rosacea. It is very common in Boston, where I practice, and parts of the country with a lot of people of northern European descent.”

Gather all the information you can. Dr. Reiser emphasized that it is important to seek all the clues you can. For example, if a child potentially has an immunological condition, such as Sjögren syndrome, “to be a good doctor you also have to take the best history possible, including checking for fluctuating vision, floaters, joint soreness—these can all manifest in children.”

Punctal Plugs for Children

Although punctal occlusion is a standard therapy for dry eye in adults, it is rarely considered for children. Dr. Nischal is a coauthor of a recent study that evaluated the safety and efficacy of punctal plugs in children with dry eye syndrome.1 This retrospective case series of 25 patients (median age 7 years) concluded that the plugs offer a safe, effective form of treatment, especially as children may have poor compliance with a frequent lubrication regimen.

Reasons for trying punctal plugs. Indications for punctal plug insertion were based on presence of ocular surface changes and poor tear film meniscus, with previous unsuccessful management by lubrication and topical medication alone.

“Children hate getting drops in their eyes; everyone gets frustrated because the child is not improving,” Dr. Nischal said. “The real questions are these: How disruptive is putting drops in, and how much benefit is there? It’s hard for children to do at school. So, how can we deliver the care without disruptions? That’s why I think plugs are such a good idea.”

Results. All of the study patients showed improvement in the signs and symptoms of ocular surface disease. In addition, visual acuity improved in 15. The authors note that this is particularly important due to the ocular development that occurs in childhood.

Dr. Nischal said that one of the problems with the use of punctal plugs is a 25 percent extrusion rate, due to rubbing, scratching, and manipulation. He replaces the plugs every six months.

“I envision, in five years, understanding a little more about the physiology of the ocular surface in children. Perhaps there will soon be a drop that solidifies, like a gel, to do what a punctual plug does. That is in process for the adult world.”

___________________________

1 Mataftsi A et al. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(1):90-92.

|

Management Approaches

Similarities and differences. The main treatment strategies are based on tear supplementation, lubrication, and anti-inflammatory agents. Dr. Pflugfelder noted that these approaches are similar to those used in adults. The most common approach taken by general ophthalmologists is to give tear supplementation, said Dr. Colby. But if the patient has evaporative dry eye, tear supplementation alone won’t solve the problem. “You have to improve the quality of the tear secretions.”

Dr. Reiser noted that patients with rosacea-associated dry eye, for example, need stronger measures: “You treat them very differently, using lots of steroids, and systemic azithromycin to decrease ocular surface inflammation and modulate tears. It is a more chronic course, not as innocuous.”

Avoid doxycycline in children. Dr. Colby noted that one mainstay in treating adults with MGD is oral doxycycline, but she does not use it in children younger than 12 to 14 years. “It’s not for kids, due to the risk of dental staining. You can substitute oral erythromycin, which works pretty well. You can also use warm compresses and topical antibiotics.”

Severe GVHD. Dr. Pflugfelder said, “The only FDA-approved drug is Restasis [cyclosporine emulsion]. Although it’s not really approved for children, it can be useful in GVHD, which is often severe in kids—we usually have to get to higher-level therapies, which might consist of cyclosporine eyedrops or ‘tear’ drops made out of blood serum or plasma.”

The PROSE device. If dry eye is associated with severe ocular surface disease that fails to respond to standard therapies, the prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem, or PROSE lens, may be the solution. These custom-made, fluid-ventilated, gas-permeable devices vault the cornea, retaining a pool of oxygenated artificial tears over the corneal surface.2 Developed at the nonprofit Boston Foundation for Sight, the PROSE lens is becoming more widely used in adults, and it can also be effective in children, according to Deborah S. Jacobs, MD, medical director of the foundation and faculty member at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

“We have treated 60 children under age 13 from January 1996 to December 2011, half of them in the last five years. The majority have ocular surface disease, of which dry eye is a part, as their indication for treatment,” she said. “Of those children with ocular surface disease who were fitted with a PROSE lens, about half have neurotrophic cornea and half Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Children with neurotrophic cornea can be fitted in the first year if necessary and anytime through early childhood. It is difficult to fit children with SJS before age 8 because of their intense symptoms and limited capacity for cooperation.”

But, she said, “If a child has a lack of corneal sensation, usually he or she can adapt very well to PROSE treatment, and device insertion is easy. The corneas heal and clear and do very well. It can save the sight of these children, who could proceed otherwise to corneal scarring.”

Dr. Pflugfelder sees 10 to 20 or more children for the PROSE lens each year. He said that the PROSE can provide almost immediate relief when placed on the eye. “It can be a life-changing device: Vision and comfort are brought back for the wearer.”

___________________________

1 Kim SK. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17(4):344-348.

2 Gungor I et al. J AAPOS. 2008;12(3):263-267.

___________________________

Drs. Colby, Jacobs, Nischal, and Reiser report no related financial interests. Dr. Pflugfelder is a consultant for and receives research funding from Allergan.