By Jonathan Tzu, BS, James T. Handa, MD, and Irene C. Kuo, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from June 2008 and may contain outdated material.

It was late on a Friday afternoon when we first saw William Whitemarsh.* He was concerned about a sudden, painless loss of vision in the inferior field of his left eye that had started three days previously. Things seemed grayish and occluded when he looked at them through this eye. He said his right eye seemed fine and there were no other ocular symptoms.

His History

Nine days earlier, Mr. Whitemarsh, who is 60 years old, had undergone heart surgery—an uncomplicated coronary artery bypass graft combined with aortic tissue valve replacement.

His ocular history was significant for blepharitis in both eyes and, 10 years ago, he had LASIK in the left eye. His other medical history was significant for hypertension and Barrett’s esophagus.

His Exam

Visual acuity without correction was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/50 in the left. The visual acuity in the left eye did not improve with manifest refraction. Confrontation visual field testing showed an inferonasal defect in the left eye. There was no relative afferent pupillary defect. Slit-lamp examination revealed bilateral mild cataracts.

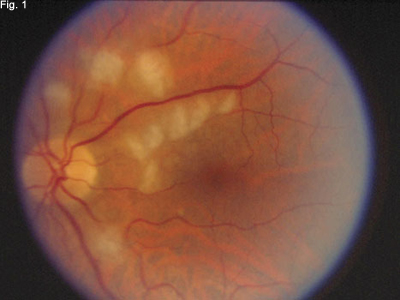

Dilated funduscopic examination was normal in the right eye. In the left eye, there were 10 fluffy, white lesions, the largest measuring one-third the size of the optic disc. The lesions appeared to be in the superficial retina. Topographically, most were located inside the superotemporal arcade, both superior and nasal to the macula, and one lesion lay inside the inferotemporal arcade. An additional lesion was located within 500 µm of the fovea. The vitreous was clear, the optic nerve head was normal and the retinal vasculature showed some arteriolar narrowing.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis included central retinal artery occlusion, branch retinal artery occlusion, commotio retinae, fat embolism and Purtscher’s retinopathy.

The appearance of Mr. Whitemarsh’s fundus and his recent history of surgery were sufficient to make the diagnosis of Purtscher’s retinopathy, which remains a clinical diagnosis. In his left eye, we could see the characteristic Purtscher flecken, which are discrete areas of ischemic retinal whitening in the superficial inner retina (Fig. 1).

Several further observations pointed to Purtscher’s retinopathy: the symptoms and signs were delayed relative to the inciting systemic event, there was no history of ocular trauma, the whitening spared the retina immediately adjacent to the arterioles, and there were no visible emboli on the fundus exam.

|

|

At Initial Presentation. The patient had lost visual acuity in his left eye. When we examined the retina of that eye, we observed fluffy, white lesions.

|

Treatment

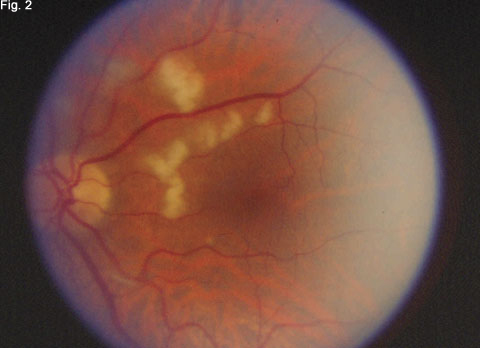

We took a conservative approach and reassured Mr. Whitemarsh that his vision would most likely improve over time as these lesions gradually resolved. He was reexamined two weeks later, at which point the uncorrected visual acuity in the left eye had improved to 20/25. Most of the lesions had decreased in size and/or coalesced (Fig. 2).

|

|

Two Weeks Later. His visual acuity had improved from 20/50 to 20/25, and most of the retinal lesions had decreased in size and/or coalesced.

|

Discussion

In 1912, Otmar Purtscher described “angiopathia retinae traumatica” in a series of five patients with decreased visual acuity after head trauma. Each patient had multiple areas of retinal whitening and hemorrhage in the posterior pole of both eyes.1 Since then, the condition has become known as Purtscher’s retinopathy.

It is associated with a variety of conditions. Purtscher’s retinopathy has most commonly been associated with head or chest trauma, and long bone fractures. However, there are case reports of Purtscher’s retinopathy in association with acute pancreatitis, fat embolic syndrome, chronic renal failure, childbirth, various connective tissue disorders, amniotic fluid embolization and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.2

It has several typical findings. Patients typically present from 24 to 48 hours after the initial trauma or inciting event with decreased visual acuity, loss of visual field or both. Purtscher’s retinopathy more commonly occurs bilaterally, although unilateral cases have been reported.3 Fundus findings in Purtscher’s retinopathy are typically restricted to the posterior pole and can include Purtscher flecken, retinal hemorrhage and optic disc swelling. Purt-scher flecken are cotton-wool spots that are polygonal and are approximately one-third of the disc size. Fluorescein angiogram demonstrates early hypofluorescence followed by late leakage from areas of ischemia.2

Its pathogenesis remains uncertain. Several mechanisms of pathogenesis have been suggested, but emboli are thought to be the most likely etiology. The emboli may consist of air, fat, platelets, blood or a complement-mediated leukoaggregate. It is thought they become lodged and disrupt circulation in the precapillary arteriolar system.2

What etiological evidence does histopathology provide? A patient with Purtscher’s retinopathy who died from acute pancreatitis showed focal areas of retinal edema and cystoid degeneration. There were focal areas of disrupted inner retinal layer architecture that abruptly transitioned to normal retina. Retinal arterioles and choroidal vessels contained occlusive fibrin material.2 Postmortem histopathology from another patient with pancreatitis-associated Purtscher’s retinopathy had all of these findings except for the vascular occlusion.2

Watch and wait may suffice. The majority of patients with Purtscher’s retinopathy recover their visual acuity and visual field without intervention. There have been reports of treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone, experimental use of papaverine (for its vasodilatory properties) and proposed therapy with hyperbaric oxygen,2 but no treatment has proved superior to observation and time. It is possible that local intraarterial recombinant tissue plasminogen activator also could be tried in the future. The degree and location of occlusion and subsequent ischemic injury to the neurosensory retina may be critical determining factors in visual recovery.

Mr. Whitemarsh’s Case

Mr. Whitemarsh represents a case of unilateral Purtscher’s retinopathy after open-heart surgery for bypass graft and valve replacement. To our knowledge, Purtscher’s retinopathy has not been reported previously in the literature in association with such surgery.

The well-documented increase in the number of emboli in the circulation after open-heart surgery suggests multiple emboli served as the likely inciting event for our patient’s retinopathy.

Given the prevalence of coronary artery bypass grafts, it may be worth considering Purtscher’s retinopathy in cases of vision loss after bypass surgery.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Purtscher, O. Graefe’s Arch Ophthalmol 1912;82:347–371.

2 Agrawal, A. and M. A. McKibbin. Surv Ophthalmol 2006;51:129–136.

3 Burton, T. C. Ophthalmology 1980;87:1096–1105.

___________________________

Mr. Tzu is a third-year medical student at Johns Hopkins. Dr. Handa is an associate professor of ophthalmology, and Dr. Kuo is an assistant professor at the Wilmer Eye Institute.