By Kevin M. Shiramizu, MD, and Sherwin J. Isenberg, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from September 2004 and may contain outdated material.

Initially, the parents of Roman Valenzuela* were happy and relieved. He was a full-term baby, born vaginally and without any complications. In short, everything seemed to be going well. However, when Roman was about 1 month old, they noticed that he tended to tilt his head to the right.

The Misdiagnoses

First Misdiagnosis. Roman’s pediatrician informed them that he just had “weak neck muscles” and that the problem would go away in a month or so. Unfortunately, he continued to tilt his head, although he achieved all of his developmental milestones appropriately.

Second Misdiagnosis. When Roman was 6 months old, a consulting neurologist told his parents that he might have some nerve or muscle injury.

Third Misdiagnosis. Mr. and Mrs. Valenzuela then sought the opinion of a local pediatric ophthalmologist, who diagnosed Duane’s syndrome and suggested surgery to correct this congenital abnormality. Surgery was planned for two months later, but Roman’s mother did her own research and did not see many of the signs listed under Duane’s syndrome. Fearing that Roman would receive the wrong type of surgery, she sought another opinion with us.

|

|

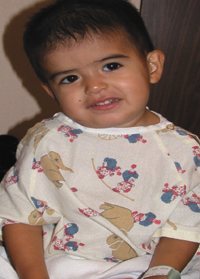

Fig. 1 The patient appeared to have a chronic right head tilt.

|

We Get a Look

At this point, Roman was 18 months old (Fig. 1). Roman’s parents reported that there was no history of developmental delay or head trauma and no family history of strabismus or any ophthalmic disease.

Roman fixed and followed well with each eye and demonstrated a right head tilt of 12 to 14 degrees and some right hemifacial hypoplasia. In forced primary position (when his head was held straight), there was a left hypertropia of 18 prism diopters. In left gaze, there was no change in the hypertropia, but in right gaze, it increased to 35 PD. The left hypertropia was fairly similar in up-gaze (22 PD) and down-gaze (20 PD). There was no hypertropia in forced right head tilt, but it worsened to 30 PD in forced left head tilt. At near, there was a left hypertropia of 12 PD. In addition, there was marked overaction of the left inferior oblique muscle and underaction of the left superior oblique muscle. Roman seemed to perceive the fly in stereopsis testing.

The rest of the examination was unremarkable except for mild excyclotorsion on funduscopic examination of the left eye.

Surgical Correction

Based on his examination and history, we diagnosed Roman with a congenital left fourth nerve palsy causing torticollis and a mild hemifacial microsomia. Roman’s parents agreed to surgery to explore the left superior oblique to look for anatomical anomalies and a possible left inferior oblique recession.

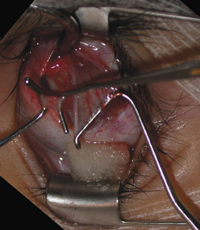

In surgery, forced duction testing revealed left superior oblique tendon laxity (Fig. 2). Direct examination of the tendon also revealed laxity demonstrated by easily elevating the tendon several millimeters off of the globe. It was decided to correct this anomalous laxity by tucking the tendon. The amount to be tucked was determined by estimating how large a tuck would produce a mild restriction to elevation in adduction. Using a tendon tucker, the tendon was overlapped by 7.5 millimeters and sutured, resulting in a 15 mm reduction in length. In addition, the left inferior oblique muscle was recessed 13 mm.

|

|

Fig. 2 Forced duction testing revealed left superior oblique tendon laxity.

|

Etiology of Ocular Torticollis

Infants often present with torticollis. This is a sign and not a specific diagnosis.

Ocular dysfunction can create compensatory head positions depending on the muscles involved. A good test to differentiate nonocular torticollis and ocular torticollis is the cover test. Covering the affected eye will usually result in spontaneous correction of the head tilt in ocular torticollis, but this will not be the case in nonocular torticollis.

There are many possible nonophthalmic causes, infection, neurologic disorders, osseous etiologies and posterior fossa tumors. Other etiologies include paroxysmal torticollis of infancy, drug-induced torticollis, spasmus nutans and inflammatory conditions such as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

Congenital muscular torticollis is one of the most common causes. This is associated with a difficult or breech birth or may be hereditary.

In assessing ocular dysfunction, the three-step test is a fundamental tool. In Roman’s case, this test pointed to left superior oblique paresis, since he had a left hypertropia in forced primary gaze that worsened on right gaze and forced left head tilt. The superior oblique muscle is the major depressor in adduction and the major intortor in all positions of gaze. Manifestations of superior oblique palsy include ipsilateral hypertropia and excyclotorsion. Patients may complain of vertical diplopia or eyestrain. The classic sign, as seen in Roman’s case, is a contralateral head tilt. Congenital cases are usually sporadic and rarely familial, and they can present later in life, having been undiagnosed earlier.

Significant facial asymmetry is often found to correlate with the side of the head tilt in congenital superior oblique paresis. It may occur from deformational molding of the face and skull from the infant sleeping with the head turned predominantly to one side during the first six to 12 months of life. Some surgeons contend that early surgery should be done to prevent this complication.1

In a survey of 190 superior oblique palsy cases undergoing surgical therapy, 28 percent were found to be acquired and 72 percent were congenital.2 Of the congenital cases, 37 percent were found to have facial asymmetry. Surgically, 93 percent underwent inferior oblique weakening, 37 percent underwent vertical rectus recessions, 18 percent underwent superior oblique tuck or resection and 8 percent underwent the Harada-Ito procedure. Overall, 92 percent reported relief of symptoms.

One study revealed that 87 percent of congenital superior oblique palsy cases demonstrated a structural abnormality of the superior oblique tendon.3 The abnormal tendons were either redundant, misdirected or absent. For congenital laxity of the superior oblique tendon, another study cited an average tuck of 12 mm, with 17 percent of patients needing re-operation for residual head tilt or diplopia.4 In any case of suspected congenital superior oblique paresis, it is important to examine the superior oblique tendon and correct any malformation.

Three Months Later

Roman did very well after surgery, and his parents were very pleased that his head tilt was gone. On examination, there was no hypertropia in primary gaze and left hypertropia of only 3 PD in far left gaze and far down-gaze.

_______________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

_______________________________

1 Goodman, C. R. et al. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1995;32(3):162–166.

2 Helveston, E. M. et al. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1996;94:315–328.

3 Helveston, E. M. et al. Ophthalmology 1992;99(10):1609–1615.

4 Helveston, E. M. et al. Aust J Ophthalmol 1983;11(3):215–220.

_______________________________

Dr. Shiramizu is a fellow in vitreoretinal surgery at the University of Southern California and Dr. Isenberg is professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, Los Angeles.