By Kevin Talbot, MD, Sasha Strul, MD, and Syed Gibran Khurshid, MD, MMS, FRCS(Ed), FRANZCO, FACS

Edited by Steven J. Gedde, MD

Download PDF

Andrea McJones,* a 66-year-old retiree, showed up at our emergency department with a chief complaint of vision loss in her left eye. Our first-year resident was called in to see Ms. McJones, who said that the vision in her left eye had deteriorated rapidly over the previous 48 hours and described it as “like looking through a gray veil.”

History. Ms. McJones told the resident that she hadn’t experienced any pain and also denied any associated trauma, flashes, floaters, photophobia, or recent febrile illness. Her past ocular history was significant only for high myopia of –7.00 D in each eye.

Initial exam. Ms. McJones had normal visual acuity in her right eye but only hand motion vision in her left. Her ocular movements were full, and her pupils were equally round with a trace afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. The confrontation visual field was full to counting fingers in the right eye and full to movement in the left. Her intraocular pressure was normal. The slit-lamp examination of her anterior segment was unremarkable in both eyes. She was phakic, and Schaffer’s sign (pigment granules in the anterior vitreous) was absent bilaterally.

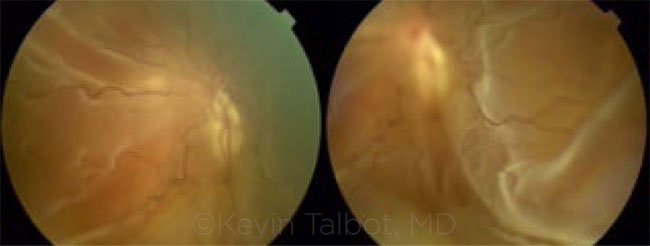

A 360-degree examination of both retinas, using indirect ophthalmoscopy with a 20-D lens, revealed no lattice degeneration, retinal breaks, or tears in the right eye—but the left eye was found to have a total retinal detachment without an identified causative break or shifting subretinal fluid. At this point, the first-year resident contacted us for help.

|

|

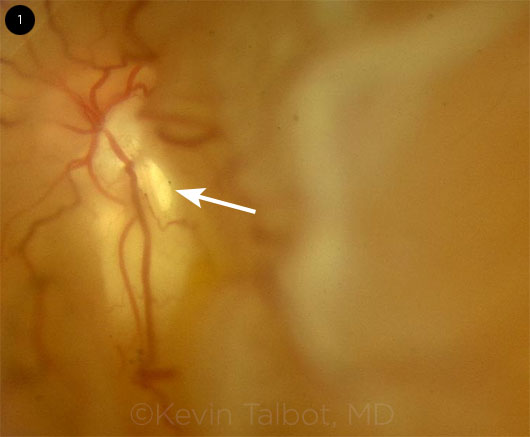

SURPRISE IN THE LEFT EYE. Peripapillary retinal break within 1 disc diameter of the optic disc.

|

Discussion and Next Steps

Successful repair of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) relies on identifying the causative retinal break(s) so they can be sealed off.1 Typically, performing a B-scan ultrasound exam for an underlying mass is appropriate if there is concern about possible exudative retinal detachment. Even though Ms. McJones’ detachment was rhegmatogenous, we performed a B-scan to confirm that there was no mass.

In the case of a total retinal detachment without any identifiable peripheral breaks, the next step should be to thoroughly examine the disc and peripapillary retina. In this high myope, the examiner initially focused attention on the periphery and overlooked the causative peripapillary break, which was subsequently found within 1 disc diameter of the optic disc (Fig. 1).

Peripapillary breaks. It has been well reported that retinal detachments in patients with morning glory disc anomaly are commonly due to a disc-associated break.2 Peripapillary microholes have also been the cause of symptomatic RRD in pathologic myopia with posterior staphylomas.3 Our case illustrates that clinicians should thoroughly examine for peripapillary breaks in all RRD patients, even in those patients with discs that appear normal.

|

OVERLOOKED IN THE INITIAL EXAM. Although a thorough peripheral exam was negative for any retinal holes, tears, or breaks, indirect ophthalmoscopy revealed a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

|

Treatment. Commonly, scleral buckling procedures may be selected (with or without pars plana vitrectomy) when repairing retinal detachments with unseen breaks. However, a scleral buckle would not have addressed the cause of RRD in our patient. Careful attention to the disc area in the clinic allowed for proper preoperative planning and counseling of the patient.

Treatment options for patients with peripapillary retinal breaks causing RRD are limited given the area of retina that would require barricade laser and the limited utility of gas tamponade or scleral buckles. We treated Ms. McJones with a pars plana vitrectomy, conservative barrier laser, and long-term silicone oil. We won’t remove the silicone oil until the clinical exam is indicative of retinal reattachment based on laser scarring. The silicone oil will otherwise remain in situ long-term.

When we saw Ms. McJones at her 1-month postop follow-up, the retina was attached despite the open break, and her best-corrected visual acuity had improved to 20/80.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Saxena S, Lincoff H. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2001;49(3):199-202.

2 Yamakiri K et al. Retina. 2004;24(4):652-653.

3 Dinah CB et al. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1089-1095.

___________________________

Dr. Talbot is a first-year resident, Dr. Strul is a third-year resident, and Dr. Khurshid is a professor of ophthalmology and a vitreoretinal specialist; all 3 are in the department of ophthalmology at the University of Florida, Gainesville. Relevant financial disclosures: None. This article was supported in part by an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Membrane Removal

Watch a brief video (courtesy of the Aravind Eye Care System) that shows an RRD with proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR). The video, which is shorter than 3 minutes, shows how to manage the PVR membranes and reattach the retina.

|

More at the Meeting

Grand Rounds: Cases and Experts From Across the Nation (Sym49) will feature a series of memorable case reports at AAO 2016 in Chicago. Nicholas J. Volpe, MD, the event’s chair, has solicited submissions from residents across the country and will select the most interesting and best teaching cases for presentation. When: Tuesday, Oct. 18, 10:15-11:30 a.m. Where: Room S406a. Access: Free.

|