By Nandini G. Gandhi, MD, Thomas A. Oetting, MD, and Pat Kirby, MD

This article is from January 2008 and may contain outdated material.

About four months ago, Patricia Petersen* was driving to work when she suddenly noticed “water spots” in both of her eyes. They moved around a bit but never went away. She assumed she was seeing dirt on her seldom-washed windshield and gave it no more thought—other than wondering what she had done with her squeegee.

It was when the spots survived a thorough car wash that Ms. Petersen, who was 46 years old, began to worry. She described the problem to her primary care doctor, who referred her to a local ophthalmologist. This next doctor was concerned about a possible transient visual obscuration and ordered visual field testing and a brain MRI. Both were normal. Because of the persistence of the floaterlike spots, she was referred to our clinic for further workup.

We Get a Look

When we saw Ms. Petersen, she told us that she was still seeing the bothersome floaters in both of her eyes. There were too many to count, she said, and they had not changed over the last four months. She was happy, however, that her vision was unchanged and that she was generally feeling quite well.

On our exam, her vision without correction was 20/20 –1 in the right eye and 20/20 –1 in the left. Her IOP by applanation was markedly elevated at 40 mmHg in the right eye and normal at 19 mmHg in the left. Her angles were open 360 degrees by gonioscopy without peripheral anterior synechiae or neovascularization of the angle. She had mild anisocoria with a right pupil of 4 mm and a left pupil of 3.5 mm, constricting to 3.5 mm and 2.5 mm, respectively. We saw no relative afferent pupillary defect. Her ocular motility was full in both eyes, and her Goldmann and confrontation visual fields were full.

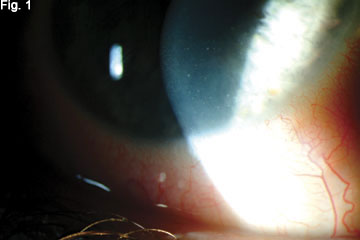

Her slit-lamp exam was notable for mild conjunctival hyperemia in the right eye. We also noted that the right eye had small stellate and granulomatous keratic precipitates in the inferonasal aspect of the cornea (Fig. 1). With a 0.2-mm beam, we noted five to 10 white blood cells and mild flare in the anterior chamber of the right eye. She also had a nodular irregularity of the iris at approximately 3 o’clock with surrounding dilated blood vessels and thickening of iris stroma (Fig. 2). The left eye was normal at the slit lamp.

Her dilated funduscopic exam revealed increased cupping of the right disc as compared with the left disc but without swelling or pallor. Her macula, vasculature and peripheral retina were normal in both eyes.

|

|

|

AT THE SLIT-LAMP. We found granulomatous keratic precipitates (Fig. 1) and nodular irregularity of the iris (Fig. 2).

|

Our Differential Diagnosis

We felt her exam was consistent with granulomatous uveitis, and our differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome and such infectious etiologies as syphilis, Lyme disease and tuberculosis. The fact that the patient was otherwise completely asymptomatic made it difficult to distinguish among these on our review of systems. Because some of the keratic precipitates were stellate and she had ipsilateral elevated ocular hypertension, we added atypical Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis to our differential diagnosis.

The workup. We initiated a workup to determine the cause of the uveitis and associated findings. The patient was scheduled for a chest x-ray and had RPR, ANA and serum ACE levels drawn prior to leaving the clinic. She was started on prednisolone four times daily in the right eye and timolol twice daily in the same eye. We asked her to return in one week.

The initial results. Prior to her follow-up appointment, we received the radiology and lab results. Her ANA titers were normal at less than 1:40, and her RPR was nonreactive, but her ACE was markedly abnormal at 113 IU/L (normal 8 to 52 IU/L) and her x-ray revealed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 3).

One week later. When Ms. Petersen returned, she denied changes in visual acuity but still reported the persistence of floaters in both eyes. She reported good compliance with her prednisolone and timolol eye drops.

Her visual acuity without correction was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/20 –1 in the left. Her IOP in the right eye had normalized to 12 mmHg, and in the left eye was stable at 14 mmHg. Her pupil exam was unchanged.

Her slit-lamp exam was notable for 0.5-mm noninflamed follicles in the nasal lower palpebral conjunctiva of her left eye and in the temporal upper palpebral conjunctiva of the same eye (Fig. 4). No white blood cells were visible in the anterior chamber, and there was no flare. The nodular irregularity in the iris was no longer visible.

A conjunctival biopsy was taken of the inferior palpebral conjunctiva. We told her to continue the prednisolone and timolol in the right eye; she was scheduled for follow-up in two weeks.

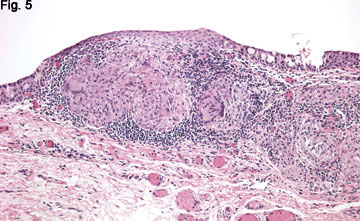

The biopsy results. The specimen revealed multiple noncaseating granulomas. Special stains for organisms—periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) with diastase and Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain—were negative (Fig. 5). This finding is very suggestive of sarcoidosis.

|

|

|

AT FOLLOW-UP. We informed Ms. Petersen that her chest x-ray had revealed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 3). We noted noninflamed follicles in the palpebral conjunctiva of her left eye (Fig. 4) and took a biopsy (Fig. 5).

|

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease with diverse manifestations. In the United States, it has an incidence of approximately six cases per 100,000. It is slightly more common in women and three to four times more common in African Americans than in Caucasian Americans.1 The disease is thought to have two peaks of incidence—one between 20 to 30 years of age and the other between 50 to 60 years.2

What causes the disease? This isn’t known for sure, but it is thought to involve an exaggerated immune response (specifically of macrophages and helper T-cells) to a self or nonself antigen in genetically predisposed individuals.2 While numerous microorganisms have been implicated as possible triggers, none have been shown to have a direct causative relation to the disease. The upregulated and poorly modulated inflammatory response results in granulomas in the affected organs.

Pulmonary involvement? This is present in nearly all patients with sarcoid. Patients often present with symptoms of chest pain and dyspnea combined with constitutional symptoms of malaise, fever and weight loss. Extrapulmonary sarcoid spares almost no organ system and can present in a myriad ways.

Ocular involvement? This occurs in 25 to 60 percent of patients with systemic sarcoid. Indeed, the disease leaves very few parts of the globe and adnexa untouched.2 Lacrimal gland involvement can present as painless swelling of the lateral upper lids. Sarcoid can also result in scleritis, episcleritis and, as seen in our patient, conjunctival granulomas. “Mutton-fat” granulomatous keratic precipitates are often seen on the inferior aspect of the cornea. In the chronic forms of this disease, nodules on the iris (Busacca nodules) or at the pupillary margin (Koeppe nodules), as well as posterior/anterior synechiae, are often seen. The posterior segment is involved in nearly 30 percent of cases of ocular sarcoid.1 Vitritis often appears as opacities in the inferior vitreous in clusters (“snowballs”) or linear arrangements (“string of pearls”). Vasculitis can be seen as focal narrowing of vessels and exudative lesions or “candle-wax drippings.” Multifocal choroiditis can occur with lesions distributed predominantly inferior and posterior to the equator. Finally, optic nerve involvement can cause papillitis and/or disc edema and often suggests more extensive disease of the central nervous system.

Definitive diagnosis? This requires both suggestive clinical findings and a tissue biopsy showing noncaseating granulomas. Supporting evidence that is highly suggestive but not definitive include chest radiograph (showing hallmark bilateral lymphadenopathy), elevated serum ACE (secreted by the macrophages within granulomas, elevated in 60 to 80 percent of patients with sarcoid), elevated lysozyme, elevated alkaline phosphatase, hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria.

The treatment goal is immunosuppression. Treatment usually begins with topical steroids, as in the case of our patient. Cycloplegics may also be necessary to prevent posterior synechiae. Posterior segment involvement and refractory anterior segment pathology usually call for systemic steroids or other immunosuppressive agents.3

Ms. Petersen’s case is instructive. While it was dramatic to see the reversal of her uveitis and iris findings, this case demonstrates that Eye M.D.s can be the front line in identifying systemic medical conditions and in making tissue-diagnoses in a minimally invasive way.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

Dr. Gandhi is a resident, Dr. Kirby is a professor of pathology and Dr. Oetting is professor of clinical ophthalmology. All three are at the University of Iowa.

___________________________

1 Bonfioli, et al. Semin Opthalmol 2005;20:177–182.

2 Rothova, A. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:110–116.

3 Jones, N. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2002;13:393–396.