By Andrea V. Gray, MD

Edited By Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from July/August 2005 and may contain outdated material.

Ann Morris, MD,* a 55-year-old cardiologist, presented for her routine eye exam complaining of three episodes in the past two weeks of blurred vision in the left eye. Her episodes included general blurriness and possibly a color change centrally. She admitted to extreme stress lately due to a high workload, being a single mom with teenage twin boys, and dealing with the abrupt death of a colleague. She reported that her blood pressure is usually low. She had no other medical history, and she is thin and fit. Her only medication was Fosamax (alendronate sodium).

On examination, Dr. Morris was able to achieve 20/20 vision in each eye with the appropriate refractive correction. Amsler grid and color plates were normal. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment revealed no abnormalities. Pupils were normal, as were extraocular motility and confrontation visual fields.

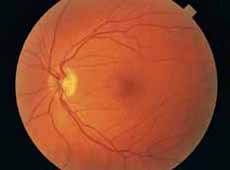

A surprise awaited on the fundus examination of the left eye. Scattered throughout the posterior pole in all four quadrants were dot hemorrhages. There were no abnormalities of the disc. There were no exudates or edema.The retinal veins and arteries were normal in appearance. Auscultation of both carotid arteries was unremarkable, and her blood pressure was normal. Hemorrhages had not been present on her previous eye examination one year ago.

The patient stated that she had an informal carotid duplex a few weeks earlier when her practice acquired a new Doppler probe. Results were unremarkable. She had been exposed to occupational levels of radiation in the course of working in the cardiac catheterization lab. There was no history of trauma.

I ordered a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, chemistry panel and a fasting blood glucose test. All lab values were within normal limits.

Dr. Morris requested to see a retinal specialist, who performed a fluorescein angiogram. The results, which were normal, included an artery-vein transit time of eight seconds.

Two months later, the hemorrhages had completely and spontaneously resolved.

|

|

What’s Your Diagnosis? In the left eye, intraretinal hemorrhages were present in all four quadrants of the posterior pole. There were no disc abnormalities.

|

Considerations

Systemic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, blood dyscrasias and anemia are all known to be associated with retinal hemorrhages, but this patient did not have any systemic pathology upon laboratory investigation. Also, the unilateral presentation in this patient was atypical for retinopathy due to systemic disease. The exception would be unilateral carotid disease or ischemia, and the patient’s normal carotid duplex study helped to eliminate that possibility. Fundus fluorescein angiography is also helpful in ruling out ischemia. In an eye affected by diabetes, hypertension or ischemic processes, fluorescein angiography will likely show areas of capillary drop-out, and abnormalities such as these were absent in this patient.

Also of note, traumatic injury to the head may result in Terson’s syndrome: multiple superficial intraretinal or preretinal hemorrhages that often resolve with full visual recovery. Severe head or chest trauma can lead to retinal hemorrhages and whitening, usually around the optic disc, termed Purtscher’s retinopathy. It has been suggested that this retinopathy results from the occlusion of small arterioles by intravascular particles such as fibrin clots, platelet-leukocyte aggregates, fat emboli, air emboli or other particles of similar size. Purtscher’s retinopathy also may be associated with nontraumatic systemic diseases such as pancreatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and chronic renal failure. Taking a good history from the patient can help eliminate these diagnostic possibilities.

In this case, the occupational exposure to radiation caused me to consider briefly the diagnosis of radiation retinopathy. However, there was no excessive radiation output noted on the dose-monitoring devices worn by personnel working in the cardiac catheterization lab. Furthermore, as radiation retinopathy includes capillary drop-out and endothelial damage, we would have expected to see angiographic microvascular abnormalities. The exact dose of radiation required to produce clinical retinopathy is unknown, but it is estimated at 15 to 60 Gy. The incidence of retinopathy steadily increases with doses greater than 45 Gy. The lens is typically more sensitive to radiation effects than the retina, so a cataract would be expected in an eye with radiation retinopathy from an external radiation source.

|

|

After Treatment. Two months later the hemorrhages in the left eye had completely resolved.

|

Narrowing It Down

Another possibility was venous stasis syndrome, a subcategory of central retinal vein occlusion in which there is only a partial occlusion, which may be transient. Heightened cortisol levels arising from stress may contribute to the pathology by increasing susceptibility to clot formation. The patient volunteered that she has a tendency to become dehydrated, which also may have predisposed her to venous stasis. I recommended that Dr. Morris take a daily aspirin and maintain good hydration in case venous stasis was the cause of her retinal hemorrhages and symptoms. But because of her normal vascular transit times and lack of other findings typical of carotid occlusive disease or vein occlusion, I did not feel that this diagnosis was as likely in my patient. Patients with ocular ischemic syndrome may additionally complain of pain or lengthened dark-light adaptation time, but Dr. Morris did not mention this. Also of note, this patient did not have any nerve fiber layer hemorrhages, which are typically present in central retinal vein occlusion.

I considered a new entity recently described in the journal Eye: benign idiopathic hemorrhagic retinopathy.1It is characterized by acute onset and is usually a unilateral, deep hemorrhagic retinopathy without abnormalities in the retinal vasculature or optic discs. In all of the cases described, fluorescein angiography demonstrated normal arteriovenous flow, without capillary nonperfusion, vessel or disc leakage. None of the patients had macular edema or cotton-wool spots, and all had complete, spontaneous recovery of visual acuity in the affected eye within four months. Systemic examination in all cases was normal. This diagnosis seemed the most likely for my patient.

Follow-Up

Dr. Morris returned for follow-up eight months after the initial presentation, and the fundus continued to be without hemorrhages or vasculopathy. She has not had any more visual symptoms. She is managing to deal with the stress of her job and family life.

_____________________________

*Patient name is fictitious.

_____________________________

1 Baker, G. R. and R. H. Grey. Eye 2002; 16(1):107–108.

_____________________________

Dr. Gray is a comprehensive ophthalmologist in private practice in Roseburg, Ore.