By Kara Della Torre, MD, Leonard Bielory, MD, Roger E. Turbin, MD, Seena Aisner, MD, and Larry P. Frohman, MD

Edited By Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from October 2006 and may contain outdated material.

At 23-years-old, Brigitte Erzulie* should have been full of plans for the future. Instead, the young Haitian was fretting about her vision, which had been slowly declining for five years. She had not noticed any blind spots, nor any difference between her day and night vision. There had never been any pain in her eyes, but she noticed that they had seemed drier over the past five years.

Ms. Erzulie also commented that she had had a dry mouth since she was a child. There was a chronic rash of uncertain duration on her chin and neck. When asked about headaches, Ms. Erzulie said that she never had any. Nor did she suffer from joint pains, night sweats or difficulty swallowing. She denied any cardiac, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary or—with the exception of her visual loss—neurologic problems. She did not have diabetes mellitus, hypertension or any other systemic illness.

Apart from Depo-Provera (medroxyprogesterone acetate), she was taking no medications.

Ms. Erzulie had no family history of visual loss, cancer or connective tissue disease, and she denied a history of smoking, alcohol or intravenous drug abuse. She also denied any exposure to known toxins prevalent in the Caribbean basin, such as the cassava plant or “bush tea.”

On examination, Ms. Erzulie had 20/100 best-corrected vision in each eye with normal pupillary responses. She correctly identified six of six Ishihara color plates with both eyes. Her ocular motility was normal. The results of her slit-lamp exam were within normal limits, and her IOP was 17 mmHg in both eyes.

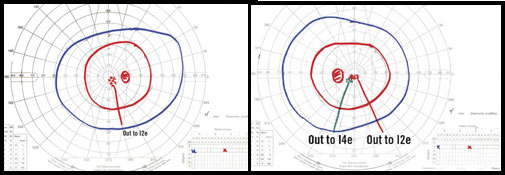

Visual field testing showed a central/ paracentral scotoma to a I-2-e test object on Goldmann perimetry. Automated perimetry of the central 10 degrees using a two-degree grid showed central depression in both eyes with a mean deviation of –7.06 in the right eye and –6.58 in the left. Her cup-to-disc ratio was 0.2 with mild carved out temporal pallor, arteriolar narrowing and a mild decrease in the nerve fiber layer in the papillomacular bundle of both eyes.

|

|

What’s Your Diagnosis.Visual field testing revealed that Ms. Erzulie had a central/paracentral scotoma. Automated perimetry showed a central depression in both eyes.

|

Differential Diagnosis

Ms. Erzulie’s history gave us much to consider. Bilateral optic neuropathy can be congenital, genetic, ischemic, toxic/ nutritional, compressive or inflammatory.

In Ms. Erzulie’s case, the gradual progressive visual loss, with onset in adulthood, made congenital, genetic and ischemic disease less likely.

Although optic neuropathy secondary to a vitamin deficiency was a consideration, toxic/nutritional optic neuropathy was not deemed likely since she did not smoke or drink alcohol and had no known toxic exposures.

Compressive optic neuropathy might fit the clinical picture of progressive painless visual loss, but discrete central scotomas are unusual in compressive lesions.

Demyelinating optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis were briefly considered, but slowly progressive visual loss would be atypical of those conditions.

A history like Ms. Erzulie’s should always prompt a search for a chronic systemic inflammatory illness or process. These include infectious etiologies—such as syphilis or tuberculosis—and noninfectious causes—such as sarcoidosis, vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus or other collagen vascular/ autoimmune systemic disease. Paraneoplastic optic nerve or cone disease could also present in this manner.

It also is important to consider nonsystemic conditions. There are rare cases of vision loss due to visual system– specific autoimmune disease that could present like this. These include autoimmune-related retinopathy and optic neuropathy spectrum, as well as autoimmune optic neuropathy.1,2

The Work-Up and Diagnosis

On Ms. Erzulie’s first visit to our clinic, we ordered a complete blood count, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a rapid plasma reagin screening test, a fluorescent treponemal antibody test, vitamin B12 and folate levels, antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and an MRI of the brain and optic nerves, including fat-suppressed, high-resolution views of the optic nerve with contrast.

All tests were within normal limits except the ANA titer, which came back as > 1:640 in a speckled pattern.

The positive ANA prompted us to check anticardiolipin antibodies and order a dilute Russell viper venom test (for lupus anticoagulants) and double- stranded DNA and rheumatoid factor assays. Of these tests, the only abnormality found was an elevated anticardiolipin IgM level of 20 U/ml (the normal range is 0 to 9 U/ml).

We then referred the patient to the department of allergy and immunology for further work-up. She was found to have marked elevations of anti-Ro/SS-A (1,837 U/ml; normal to 99) and anti-La/SS-B (1,020 U/ml; normal to 99). She also was shown to have an IgG1 level of 1,580 mg/dl (the normal range is 422 to 1,292 mg/dl). The rest of a detailed autoimmune serologic evaluation was normal.

Our patient’s marked antibody titers suggested the possibility of Sjögren’s syndrome. This is a rare cause of optic neuropathy, which is manifested serologically through elevated anti-Ro and anti-La. Ms. Erzulie underwent a lip biopsy, which is the definitive test for Sjögren’s syndrome. The biopsy was read as “unremarkable minor salivary gland with no inflammation seen” and the patient was diagnosed with a mixed connective tissue disease.

Discussion

There are five major connective tissue diseases: systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, polymyositis, dermatomyositis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Mixed connective tissue disease is an overlap syndrome that may display symptoms of some or all of these diseases, though the overlapping features often do not appear concurrently.

Sjögren’s syndrome is a disorder that is commonly associated with each of the connective tissue diseases. It is called primary SS when it occurs alone. Optic neuropathy is an uncommon manifestation of primary SS, and rarely is it the presenting feature. Secondary SS is common in mixed connective tissue disease, manifesting both through sicca symptoms (dry mouth, dry eyes, keratitis) and serologic evidence.3

In SS, the pathophysiology of optic nerve involvement is unclear. It is thought to be due in part to vasculitis, but it has also been suggested that humoral immunity could target neural tissues and thus contribute to the neuropathy.4 Because mixed connective tissue disease is considered an overlap syndrome, we infer that the mechanism of optic nerve damage may be similar.

To our knowledge, there are two published cases of optic neuropathy in mixed connective tissue disease, both of which resulted in recurrent attacks with progressive visual loss. The first case, presented by Gressel and Gressel, progressed despite therapy with corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents.5 The second case, presented by Flechtner and Baum, responded to plasmapheresis.6 Ms. Erzulie did not undergo therapy, as she presented late in her course with stable visual acuity and fields. Should she show active optic neuropathy, she would be treated acutely with corticosteroids and with immunosuppressive agents for long-term maintenance.

In cases of bilateral progressive optic neuropathy not due to a mass, a careful search for a systemic disease process is often necessary. A close working relationship with a rheumatologist or clinical immunologist is often helpful for establishing a diagnosis and developing a treatment plan.

_______________________________

All authors are affiliated with the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-New Jersey Medical School in Newark. Dr. Della Torre earned her MD this year. Dr. Bielory is director of allergy, immunology and rheumatology. Dr. Turbin is associate director of neuro-ophthalmology. Dr. Aisner is vice-chairman of pathology. Dr. Frohman is vice-chairman of ophthalmology.

_______________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

_______________________________

1 Keltner, J. L. et al. J Neuroophthalmol 2001;21:173–187.

2 Kupersmith, M. J. et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:1381–1386.

3 Setty, Y. N. et al. J Rheumatol 2002;29:487– 489.

4 Moll, J. W. et al.Neurology 1993;43:2574–2581.

5 Gressel, M. G. and R. L. Gressel J Neuroophthalmol 1983;3:101–104.

6 Flechtner, K. and K. Baum J Neurol Sci 1994;126:146–148.