This article is from April 2012 and may contain outdated material.

One surgery or two? Combined or staged? With new devices available and in the pipeline, eye surgeons may be rethinking their approach to managing coexisting cataract and glaucoma.

Fifteen years ago, if a patient had coexisting cataract and glaucoma, Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, was likely to perform a combined phacoemulsification and trabeculectomy. “I thought cataract surgery would lower pressure only a couple of millimeters of mercury,” said the cataract specialist. But over time, he recognized that cataract removal was all that most of his patients needed to attain adequate intraocular pressure reduction.

Flash forward to the present. Dr. Lindstrom has joined a chorus of physicians who envision a return to the two-for-one operation. But with a twist: It doesn’t involve trabeculectomy. “If we had a really safe, minimally invasive glaucoma surgery that basically added no risk—and that could lower the pressure further and reduce the medication burden—we would all love that,” said the founder and attending surgeon of Minnesota Eye Consultants and adjunct professor emeritus of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Some possible alternatives already exist; others are in the pipeline. But nothing has yet emerged as the ideal surgical combination hoped for by Dr. Lindstrom and other cataract surgeons.

In the meantime, doctors must decide the best approach for treating the patient with coexisting cataract and glaucoma. The most common, but hardly definitive, answer is: individualize. Still, there are some branches along the decision tree that the experts agree on. “You can do a trabeculectomy first, cataract first, or both combined. Those are your three options on day one,” said David S. Friedman, MD, MPH, professor of ophthalmology and director of the Dana Center for Preventive Ophthalmology at the Wilmer Eye Institute, Baltimore.

Combined Procedure: Evidence Is Mixed

A meta-analysis by Dr. Friedman and colleagues reported that good evidence supports the finding that long-term IOP is lowered more by a combined procedure than by cataract extraction alone.1 But the evidence was graded weak to moderate for another finding: that a combined procedure is not as effective as trabeculectomy alone; adding cataract surgery to a planned trabeculectomy appears to counteract the IOP-lowering effect of trabeculectomy by approximately 2 to 4 mmHg on average. “When IOP is of paramount importance, it may be better to separate the cataract and trabeculectomy procedures,” the researchers concluded.

Kuldev Singh, MD, MPH, professor of ophthalmology and director of the glaucoma service, Stanford University, said that there are always trade-offs to consider. He noted that the benefit of addressing cataract and glaucoma in a single operation should be weighed against the risk that the combined cataract and trabeculectomy procedure is less likely to result in successful filtration than trabeculectomy alone. Yet if a trabeculectomy alone is performed prior to cataract surgery, the latter procedure could compromise a functioning bleb. In sum, he said, “There’s no high-quality evidence that performing combined cataract and trabeculectomy surgery is better or worse than doing the two operations separately.”

Debating the Three Approaches

Combined Surgery

“I think the choice is clear when a patient has an absolutely visually significant cataract and has progressive glaucoma despite the best-tolerated medical treatment that we can offer,” said Norm A. Zabriskie, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences and vice chairman and medical director of clinical services, John A. Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “In most cases, that’s a situation where we’re going to do a combined surgery.”

Dr. Zabriskie added, “We do combined surgery very successfully. The only debate is, when it’s combined do you get slightly less pressure lowering than if you do trabeculectomy alone? Perhaps. But combined surgery is still quite effective both in terms of IOP lowering and visual rehabilitation.”

Quality of life factors into Dr. Friedman’s decision to do combined surgery. “I do them when a patient needs pressure lowering soon and has a dense cataract,” he said. “Otherwise, I’ll do one or the other first, depending on the severity of each problem.”

Guidance from the PPP. The Academy’s Preferred Practice Pattern on primary open-angle glaucoma calls combined surgery a reasonable choice but endorses it cautiously and, ultimately, defers to the doctor and patient to carefully weigh the risks and benefits according to the individual situation.2 Preventing an IOP spike that could complicate cataract surgery is one presumed advantage of combined surgery, the PPPstates. Another advantage is the potential to achieve long-term glaucoma control with a single operation. Then comes the caveat: “Despite these presumed advantages, the evidence to date does not support routinely combining cataract and glaucoma surgery for all patients, because IOP outcomes with two-stage surgery are likely similar. Additionally, combined procedures are technically more complex.”

|

|

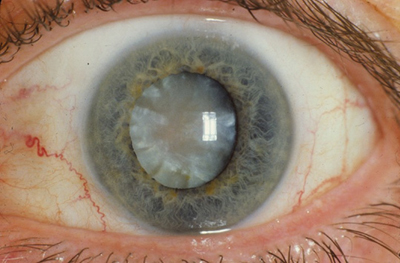

A CLEAR CASE? It’s clear that this cloudy lens should be removed with cataract surgery. But surgical decisions are more complex when the patient has coexisting glaucoma.

|

Trabeculectomy Alone

“For a person who has a small cataract that is not visually significant, I feel quite comfortable doing just trabeculectomy surgery alone,” Dr. Zabriskie said. “We shouldn’t ignore the fact that the way we do trabeculectomy has improved in the past five to seven years.” New flap construction techniques and tighter sutures with broad application of mitomycin C have reduced the problems of hypotony, flat chambers and hyphema, he said. “This in turn lowers the rate of cataract progression following trabeculectomy, in my opinion. And in the end, nothing gets the pressure as consistently low as trabeculectomy.”

Borderline cases: a harder call. What if a patient who definitely needs a trabeculectomy also has a cataract that meets criteria for removal—but the cataract doesn’t bother the patient visually? This presents a more difficult decision, said Dr. Zabriskie, because the patient will need cataract surgery, perhaps relatively soon; and the future surgery may have an adverse effect on the trabeculectomy. A recent study exploring the timing of cataract surgery after trabeculectomy suggests that the closer in time the two procedures are performed—especially within the first six months—the more likely it is that the trabeculectomy will fail.3

He explains the situation to the patient, saying that even though he or she doesn’t have many visual complaints, there may be justification for removing the cataract at the time of trabeculectomy surgery rather than at a later date. “Then we decide together what to do,” he said. “I have had patients in this setting who have felt strongly about both options.”

Cataract Surgery Alone

“Unless people really have significant pressure control issues, I like the idea of getting the lens out of the eye, which might lower pressure. Then I can go back and do the trabeculectomy if the IOP is still too high. That’s how many doctors are playing it,” Dr. Friedman said.

“I’m fine doing a cataract alone,” Dr. Zabriskie said. In these cases, the cataract is visually significant, and the glaucoma is well controlled on drops that the patient tolerates and is willing to continue. Dr. Zabriskie cited other reasons for performing cataract surgery alone, including the fact that it can now be performed through a clear corneal incision, thus preserving the conjunctiva for a future trabeculectomy if needed. He added that studies indicate cataract surgery alone can lower IOP.

IOP lowering with cataract extraction. Dr. Friedman’s meta-analysis found weak but consistent evidence that cataract surgery with phacoemulsification lowers IOP 2 to 4 mmHg. And new data from the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study group strongly support the IOP-lowering effect of cataract surgery (see “OHTS Supports Phaco Effect”).

In patients with IOP over 21 mmHg, Dr. Lindstrom has seen pressure drops of 6 to 8 mmHg following cataract surgery. In general, he has observed that the IOP reduction associated with cataract surgery is proportional to the pressure before surgery; that is, the higher the initial pressure, the greater the reduction obtained. He warned, however, that IOP can rise slightly after cataract surgery in patients with low preoperative pressures in the range of 12 mmHg.4

One explanation for cataract surgery’s ability to reduce IOP, according to Dr. Lindstrom and others, is that as the crystalline lens enlarges with age, its anterior surface moves forward, changing zonular tension and compressing the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal. Cataract extraction repositions the iris and lens, allowing the trabecular meshwork to expand and attain better outflow.4

When cataract surgery addresses both conditions, “It’s a triple win,” Dr. Lindstrom said. “We’re removing the cataract, reducing refractive error and enhancing management of the glaucoma.”

|

|

PHACO EFFECT. Cataract surgery itself reduces IOP and, in some cases, may be the only surgical intervention needed in glaucoma patients.

|

Cataract + Mild Glaucoma: New Options

Dr. Singh agreed that some cases present clearer choices than others. “When the glaucoma is mild and well controlled, we generally perform cataract surgery alone. For severe and high-risk or uncontrolled glaucoma, we commonly perform combined phacoemulsification and trabeculectomy,” he said. “There is much room, however, between these two scenarios along the spectrum of glaucomatous disease for an effective IOP-lowering procedure that is safer than trabeculectomy and can be combined with cataract surgery.”

These in-between patients might not be candidates for trabeculectomy, but they could be candidates for that safer surgery earlier alluded to by Dr. Lindstrom. And so the conversation has shifted to that set of patients who definitely need cataract surgery but who also have mild glaucoma or ocular hypertension (OHT).

The updated surgical combo. “Patients will increasingly be presented with the option of phaco plus a novel glaucoma procedure safer than trabeculectomy,” Dr. Singh predicted. “If these new procedures are truly safer than trabeculectomy,” he said, “we may accept a smaller IOP-lowering effect, particularly for patients with mild to moderate disease.”

Dr. Singh acknowledged that while cataract surgery alone may lower IOP enough for many patients, the effect varies between individuals. “This is why there is so much focus on a glaucoma procedure that can safely be combined with cataract removal,” he said. “A glaucoma surgery revolution is unfolding for those who also happen to need cataract surgery.”

Dr. Friedman agreed. “The major changes that are occurring [in the field of cataract/glaucoma comorbidity] are the addition of other surgical options at the time of cataract surgery. With these newer procedures, we have a greater chance of getting patients to a safe pressure and can avoid full-thickness procedures like trabeculectomy.” Still, he said, “Most of us who feel the pressure has to be very low are unlikely to do any of these newer procedures. None of them consistently results in pressures as low as trabeculectomy or tube shunts.” If you need 10 to 14 mmHg, you will have to do a combined surgery with external filtering, he said.

Both FDA-approved and investigational glaucoma procedures and devices are being touted as adjuncts to cataract surgery. Here are some of the contenders.

OHTS Supports Phaco Effect

A new, not-yet-published report from the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) group strongly supports earlier evidence that cataract surgery with phacoemulsification lowers IOP. In fact, the finding was strong enough to suggest that cataract surgery may be the only treatment needed to lower intraocular pressure in some patients with OHT.

“We found an 18 percent drop in IOP just from cataract surgery alone,” said Steven L. Mansberger, MD, MPH. “That’s pretty remarkable,” he said, noting that the measure of success used by many studies is an IOP reduction of 10 to 20 percent. What’s more, the effect lasted the length of the follow-up, more than two years after cataract surgery.

In other studies looking at the effect of cataract surgery on IOP, patients were usually on a number of glaucoma medications before, and were sometimes started on medication after, surgery, said Dr. Mansberger, who is associate scientist at Legacy Health System and director of glaucoma services at Devers Eye Institute. “So it’s hard to know if the decrease in IOP is due to medication or the surgery.” Findings were clearer in this study because subjects received no glaucoma medication.

The OHTS findings have implications for the role of what Dr. Mansberger calls “cataract plus” surgeries. “Doctors need to realize that part of the IOP lowering may not be from the glaucoma surgery but from the cataract surgery,” he said. “We’re very confident that cataract surgery lowers pressure a significant amount.”

|

FDA-Approved Devices

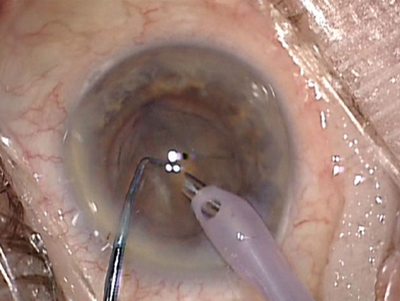

Trabectome (NeoMedix). First used in the United States in 2006, trabeculotomy ab interno with the Trabectome was designed to reestablish access to the eye’s natural drainage pathway. Performed under direct visualization with a gonioscopy lens, it removes a 60- to 120-degree strip of the trabecular meshwork and the inner wall of Schlemm’s canal with electrocautery (Fig. 1).

“It combines very nicely with cataract surgery,” Dr. Zabriskie said. “You can do it through the same approach and basically the same incision.”

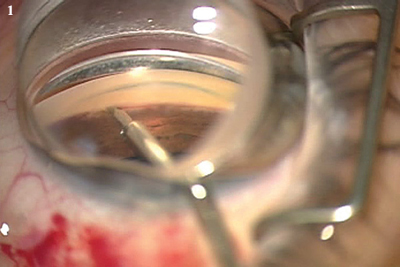

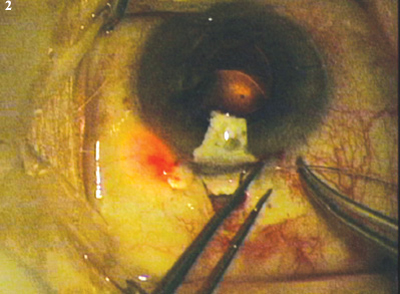

Canaloplasty (iScience Surgical). This procedure is a refinement of the older technique of viscocanalostomy. A proprietary microcatheter is inserted through a small incision to enlarge Schlemm’s canal. After 360 degrees of cannulation, the device is used to insert a suture into the entire circumference of the canal. The suture ends are tied together to provide tension to the inner wall of the canal and the associated trabecular meshwork. The tension stretches the trabecular meshwork to keep the canal open and facilitate aqueous outflow (Fig. 2).

Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (Endo Optiks). ECP applies laser energy to the ciliary processes to decrease aqueous production and, thereby, to lower IOP. It may be used in phakic, pseudophakic or aphakic eyes. However, the data supporting ECP in the published literature “are limited, in my opinion,” said Dr. Zabriskie, noting the dearth of prospective studies with long-term follow-up. “Most of what’s out there is talked about at meetings or in publications that are not peer reviewed.”

|

|

(1) TRABECTOME. Electrocautery is applied with a proprietary handpiece to ablate a portion of the trabecular meshwork. (2) CANALOPLASTY. In this surgical photo, the red light at the tip of the microcatheter indicates its position within Schlemm’s canal.

|

Investigational Devices

All of the following have received the European Union’s CE mark of approval, and clinical trials are currently under way or being organized in the United States. They represent only a few of the so-called microinvasive glaucoma surgical technologies now in development.

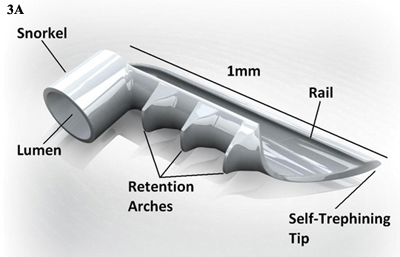

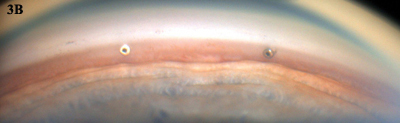

iStent (Glaukos). This titanium microstent fits into Schlemm’s canal and is designed to improve aqueous outflow by bypassing the trabecular meshwork (Fig. 3). The device is inserted through a corneal incision into Schlemm’s canal near the lower nasal quadrants and collector channels, with use of gonioscopic visualization. A prospective clinical trial involving 240 eyes randomized to cataract surgery plus iStent or cataract surgery alone found statistically significant pressure reduction on fewer medications one year after a combined stent-cataract procedure compared with cataract surgery alone.5

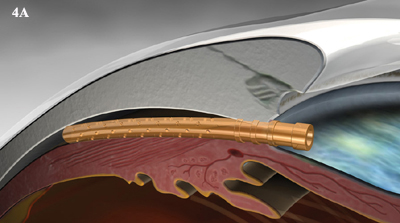

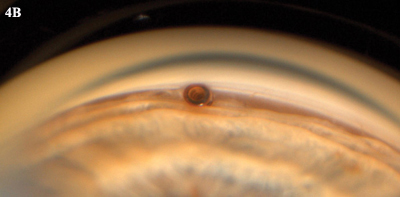

CyPass (Transcend). The CyPass Micro-Stent is designed for insertion through the phaco incision after the cataract is removed. It acts as an ab interno conduit to establish a new drainage pathway from the anterior chamber angle into the suprachoroidal space (Fig. 4).

Hydrus (Ivantis). The Hydrus Intracanalicular Implant is designed to facilitate outflow through the conventional pathway. The device has a dual mechanism of action: It creates an opening through the trabecular meshwork and dilates Schlemm’s canal.

|

|

(3B) Goniophoto shows the lumens of two iStents implanted during cataract surgery.

|

Will These Devices Change Practice?

“What you’re seeing in this field is a push to find other things we can do at the time of cataract surgery,” Dr. Friedman said. “For companies trying to build businesses around pressure-lowering procedures, cataract surgery is a natural time to do them, because you’re already in the OR. Now you can add a procedure with little additional risk,” he said. “This is a key area with a potentially large marketplace.”

High stakes. The numbers bear that out. Dr. Lindstrom said that just over three million cataract operations are performed annually in the United States. And Medicare statistics suggest that as many as 20 percent of those patients also have glaucoma or elevated IOP. Together, the two conditions constitute one of the most common comorbidities confronting ophthalmologists. Even assuming that only 10 percent of those cataract patients also have mild glaucoma or OHT, 300,000 patients might benefit from some other pressure-lowering surgery, Dr. Lindstrom said.

Dr. Singh said that doctors wouldn’t risk the stand-alone procedure of choice for refractory glaucoma—trabeculectomy—for many of these patients. If any of these new procedures with or without devices prove to be safe and effective, he predicted that the number of combined procedures would rise and could lead to “a paradigm shift.” But, he added, “Safety has to be near-perfect if these new procedures are to be accepted. Otherwise, you’re back to the problems seen with trabeculectomy.”

|

|

CYPASS. (4A) Schematic illustration of device bypassing the trabecular meshwork. (4B) Goniophoto of CyPass in place.

|

Why try these devices? “I am a minimalist by nature,” Dr. Zabriskie said. “I am not that big on the idea of doing a procedure, even if supposedly relatively safe, just to get someone off their drops, unless the person is asking for that or needing that in some way. There needs to be an indication for doing a procedure.” He cited cost, intolerance to the medication or inadequate pressure control as reasons to consider surgery.

However, he has used the Trabectome during cataract surgery in patients with early glaucoma or OHT who weren’t getting adequate pressure control on medication or who were intolerant of drops. “These patients didn’t need a trabeculectomy, but they needed something done to better control their IOP,” he said.

Dr. Friedman, who also uses the Trabectome, cautioned that there is limited evidence regarding the efficacy of these newer glaucoma procedures, and each procedure poses some additional risk. “For me it argues for increased non–industry-sponsored funding for trials to look at some of the newer things going on in glaucoma surgery,” he said. “The key question that you really need to ask yourself as a physician is: ‘What is likely to preserve my patient’s quality of life and vision for the rest of his or her life?’ That’s the key thought process for surgical decision making.”

___________________________

1 Friedman DS et al. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(10):1902-1913.

2 American Academy of Ophthalmology Glaucoma Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2010. Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

3 Husain R et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(2):165-170.

4 Poley BJ et al. In: Johnson SM. Cataract Surgery in the Glaucoma Patient. New York: Springer; 2009:35-49.

5 Samuelson TW et al. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(3):459-467.

Meet the Experts

DAVID S. FRIEDMAN, MD, MPH Professor of ophthalmology and director of the Dana Center for Preventive Ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute, Baltimore. Financial disclosure: Is a consultant for Bausch + Lomb, Glaukos, Merck, Pfizer and QLT.

RICHARD L. LINDSTROM, MD Founder and attending surgeon of Minnesota Eye Consultants and adjunct professor emeritus of ophthalmology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Financial disclosure: Is a consultant for Alcon, AMO, AqueSys, Bausch + Lomb, Glaukos and Transcend.

STEVEN L. MANSBERGER, MD, MPH Associate scientist at Legacy Health System and director of glaucoma services, Devers Eye Institute, both of which are in Portland, Ore. Financial disclosure: Is a consultant for Allergan and Santen and a lecturer for Merck.

KULDEV SINGH, MD, MPH Professor of ophthalmology and director of the glaucoma service, Stanford University. Financial disclosure: Is a consultant for Alcon, iScience, Ivantis and Transcend.

NORM A. ZABRISKIE, MD Associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences and vice chairman and medical director of clinical services, John A. Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Financial disclosure: None.

|