Download PDF

Eighteen cases cover the full spectrum of surgical complications, from the common to the rare—and from the spectacular save to the demoralizing outcome.

This past October, the 17th annual Spotlight on Cataract Surgery Symposium at AAO 2018 was entitled “Pressure Cooker: Managing Nerve-racking Complications.” Cochaired by Mitchell P. Weikert, MD, and myself, this four-hour case-based video symposium focused on cataract and IOL surgical complications.

Even the very best cataract surgeons suffer complications that challenge us to react, think, and operate under pressure. How and what we learn from our mistakes makes us better ophthalmologists. For this symposium, 18 cataract experts presented stressful cases in which something went wrong, with complications that tested their skills, decision-making, and nerves. What did they learn, and what would they do differently? At critical decision points during the case, the video was paused, and the attendees were asked to make clinical decisions using electronic audience response pads. Next, two discussants (who had never viewed the case) were asked to make their own management recommendations and to comment on the audience responses before the video of the outcome was shown. The audience voted for the best teaching cases and for those surgeons who displayed the most courage, both in the OR and at the podium.

Complications included anterior capsule tears (with and without posterior capsular extension), implantation of the wrong IOL, intraocular bleeding, haptic misadventures and subluxated IOLs, iris prolapse and iatrogenic iridodialysis, aqueous misdirection, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, descending nuclei and IOLs, IOL exchange complications, and capsules or zonules torn at virtually every stage of surgery. Robert J. Cionni, MD, concluded the symposium by delivering the 14th annual Academy Charles Kelman Lecture, entitled “Dealing With Damaged Zonules.”

This EyeNet article reports the results of the audience response questions, along with written commentary from the presenters and selected panelists. Because of the anonymous nature of this polling method, the audience opinions are always honest and candid and were discussed in real time during the symposium. View the videos here. The entire symposium with videos can be seen at AAO Meetings on Demand (aao.org/annual-meeting/aao-on-demand).

Finally, I want to especially thank our 18 video presenters. When we are speaking in front of several thousand attendees, we would all prefer to showcase our best cases instead of our complications. We appreciate their humility and generosity in sharing these cases with us so that we might all learn important surgical lessons from them.

—David F. Chang, MD

Cataract Spotlight Program Cochairman

Case 1: Trampolining Makes Me Jumpy

Tetsuro Oshika presented a case of a high myope undergoing phacoemulsification of a dense cataract. As most—but not all—of the nucleus was removed, the posterior capsule was noted to be extremely floppy, and it started trampolining toward the phaco tip. Dr. Oshika stopped phaco to consider how to remove the remaining nuclear fragments. (Video.)

Q1.1 What is the most likely etiology of the bulging and trampolining posterior capsule in this eye?

| Aqueous misdirection syndrome |

8.8%

|

| Shallowing of the anterior chamber |

7.9%

|

|

Weak zonules

|

70.2%

|

| Anterior vitreous detachment |

6.1%

|

|

Other (e.g., capsular anomaly)

|

7.0%

|

Tetsuro Oshika During surgery, there was significant billowing of the posterior capsule while the anterior capsule behaved normally, showing no sign of zonular weakness. The anterior chamber was deep, without positive vitreous pressure. It seemed that the Wieger ligament was detached from the posterior capsule, and the connection between the anterior hyaloid membrane and the posterior capsule was lost. Because the latter was no longer supported by the Wieger ligament, it became significantly floppy, remarkably increasing the risk of aspirating the posterior capsule with the phaco tip. I decided to suspend phaco and implant the IOL in the bag first and then resumed phaco to remove the remaining nuclear fragment over the IOL. Before resuming phaco, I injected a dispersive ophthalmic viscoelastic device (OVD) fully into the anterior chamber in order to prevent the nuclear fragment from moving around on the IOL and damaging the corneal endothelium. Only torsional phaco was used without longitudinal power so that thermal burn of the incision could be avoided with the anterior chamber filled with dispersive OVD.

Q1.2 What would you do to prevent posterior capsular rupture with this trampolining posterior capsule while removing the last nuclear fragment?

|

Insert a capsular tension ring (CTR), then phaco

|

16.2%

|

|

Repeatedly inject OVD

|

43.0%

|

|

Perform a pars plana anterior vitrectomy/tap, then phaco

|

1.7%

|

|

Implant an IOL first, then finish phaco over the IOL

|

36.9%

|

|

Manually extract the nucleus

|

2.2%

|

George Beiko Faced with this clinical observation of a trampolining posterior capsule, it is important to consider the cause. The likely cause would be either generalized zonular laxity or localized zonular loss. In either case, I would keep my phaco tip in the anterior chamber and introduce a dispersive OVD through the paracentesis in order to fill the capsular bag and manipulate the remaining nuclear fragment into the anterior chamber. The phaco tip would be removed. I would place a CTR to try to diminish the trampolining and might also place the IOL into the bag to act as a scaffold. Emulsification would be “slow motion,” with lowered infusion. Dispersive OVD would be replaced as needed. The remaining cortex would be removed using a combination of dry aspiration, viscodissection, low flow/low vacuum I/A, and additional dispersive OVD. The final step would be to irrigate the anterior chamber with triamcinolone to detect any vitreous prolapse and, if present, to determine whether the capsular bag–IOL complex is stable. If it is unstable, then capsular support segments or rings would be considered. Vitreous, if present, would be removed via a posterior approach.

|

|

CASE 1. While the anterior capsule behaved normally, the posterior capsule became significantly floppy.

|

Case 2: A Splitting Headache

In Bill Trattler’s case, a large nasal zonular dialysis became apparent during phaco as he removed the first heminucleus. (Video.)

Q2.1 After discovering a large nasal zonular dialysis with a dense heminucleus still present, what would you do next?

| Fill the bag with OVD and resume slow-motion phaco in bag |

15.6%

|

| Implant a CTR, then resume phaco in bag |

37.1%

|

|

Implant capsule retractors, then resume phaco in bag

|

25.3%

|

| Prolapse nucleus into the anterior chamber, then resume phaco in the anterior chamber |

19.4%

|

|

Convert to manual extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE)

|

2.5%

|

Bill Trattler This case focused on the management of a patient who developed a zonular dialysis during phacoemulsification of a relatively dense cataract. After the creation of the capsulotomy, hydrodissection was performed. However, only a limited fluid wave occurred. Phacoemulsification was performed with the creation of a central groove that allowed for the nucleus to be split into halves. The first half was removed. However, when the second half was engaged with vacuum, the presence of an area of zonular dialysis became evident (Fig. 1). The vacuum was disengaged.

Audience members were relatively split on what they would recommend for the next step. The most popular recommendation was to implant a CTR to provide capsular stability. While the anterior capsule behaved normally, the posterior capsule became significantly floppy. While this is a good option, challenges can occur when a CTR is placed early in a case. The second most popular answer was to implant capsule retractors, which is an excellent recommendation. This step would hold the capsule in place and potentially prevent further extension of the dialysis. The third most popular choice—which was what was done in this case—was to prolapse the heminucleus into the anterior chamber and then resume phacoemulsification. This was accomplished with the placement of an OVD into the capsular bag and under the heminucleus, resulting in the nuclear material shifting forward into the anterior chamber. The nucleus was removed with phaco. Following this step, the cortex was carefully removed, leaving the capsule, with the zonular dialysis evident (Fig. 2A).

Mike Snyder It’s daunting when a zonular dialysis occurs during phaco, as it not only exposes the hyaloid face, which can result in vitreous loss and potential retinal sequelae, but also it can increase the chance of posterior displacement of nuclear fragments, a situation which most anterior segment surgeons loathe.

Most of the audience chose to stabilize the capsular equator. Most chose a solid restraint to the equator (some by a CTR; others by hooks), and a smaller subgroup chose to use an OVD to support the internal aspect of the capsular bag. It would be my hope that those choosing this approach would select a highly dispersive OVD. The choice to bring the remaining nucleus into the anterior chamber, selected by 19.4%, actually increases the risk of nuclear fragment loss into the vitreous cavity when compared to in-the-bag phaco in the setting of zonular dialysis. This approach does, however, minimize the risk of damage to the posterior capsule.

Conversion to a manual ECCE was the least common choice. This may reflect fading of the skills required for ECCE among the younger population of ophthalmologists.

CASE 2 CONCLUSION: The remaining nucleus was removed without a CTR or capsule retractors, and an anterior vitrectomy was performed. A large 5 clock-hour zonular dialysis was present superiorly and nasally.

Q2.2 How would you fixate an IOL with this large zonular dialysis?

|

Scleral suture a modified CTR (e.g., Cionni/Malyugin) plus an intracapsular posterior chamber (PC) IOL

|

34.6%

|

|

Scleral suture a capsular segment (e.g., Ahmed) plus an intracapsular PC IOL

|

20.0%

|

|

Implant a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus

|

29.2%

|

|

Place a PC IOL in the sulcus and iris, or scleral suture fixation of the haptics

|

4.3%

|

|

Use an anterior chamber (AC) or Artisan aphakia iris-claw IOL

|

11.9%

|

Mike Snyder In the setting of a zonular dialysis, IOL fixation can be a challenge. It is telling that there was a wide diversity of opinion among the audience members on how to best manage an IOL in this case, demonstrating that there are many reasonable alternatives.

More than half of the respondents would have chosen to place the IOL in the capsular bag and to fixate the bag to the sclera using some sort of capsular fixation device. A significant percentage expressed a preference for a CTR with an integral fixation element (either a Cionni ring or a Malyugin CTR). This would have been my personal preference as well, due to the greater structural stability of the single fixation-ring unit (versus independent fixation elements). Some preferred an Ahmed segment. While this is easier to place, it does not fully expand the bag; nonetheless, it is a fully reasonable alternative for fixation of the bag to the eye wall.

Nearly 30% of all respondents chose to place a three-piece PC IOL passively in the sulcus. While this is a reasonable option, there is a chance that the IOL will eventually find its way to the zonular dialysis and subluxate, perhaps requiring a repositioning surgery. The respondents might have selected this option for a variety of reasons, including the availability (or lack thereof) of capsular fixation devices, a low percentage of experience with subluxations in similar settings, or relative familiarity with fixation alternatives. Another strategy—not included as a response option—would involve placing a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus, then capturing the optic through the capsulorrhexis into the bag. This hybrid alternative would provide some IOL fixation without requiring transscleral or iris fixation sutures, although it might have been hard to capture the optic with such a large dialysis. The surgeon did choose passive sulcus fixation in this case, which did lead to a sustained favorable outcome.

Finally, it was interesting that nearly 12% of individuals would have chosen an AC IOL, as doing so would require significantly enlarging an existing clear corneal wound.

|

|

CASE 2. (2A) Zonular dialysis evident during phacoemulsification. (2B) Following cortical removal, the capsule is clear. The area of zonular dialysis is visible, and the surgeon must decide where to place the IOL. (2C) A three-piece IOL has been placed in the sulcus, and a 10-0 nylon suture secures the temporal corneal incision.

|

Case 3: Don’t Cry for Me

Rosa Braga-Mele presented her case of a 63-year-old with a white and brunescent mature cataract. She aspirated cortex with a needle—but as she initiated the continuous curvilinear capsulorrhexis (CCC) under dispersive OVD, the patient coughed, and the anterior capsule split from one end to the other, creating an “Argentinian flag” sign. (Video.)

Q3.1 What’s your preference for anterior capsulotomy with a mature white cataract?

| Femto capsulotomy |

16.2%

|

| Zepto capsulotomy |

2.0%

|

|

Manual CCC (after aspirating the cortex with a needle)

|

58.5%

|

| Manual CCC (without cortex aspiration) |

21.7%

|

|

Would refer this case

|

1.6%

|

Daniel Badoza In cases with an intumescent white cataract, my preferred technique for capsulotomy is manual CCC after aspiration of the cortex with needle. As it is important to keep the anterior chamber pressurized, when the main incision is made, the keratome should penetrate only 1 mm. Next, the chamber might be filled with a viscodispersive or viscoadaptive OVD. After the CCC is completed, the keratome is introduced completely through the initial incision in order to achieve the desired incision width. Manual CCC without cortex aspiration should be limited only to those white cataracts without an increased lens vault (noted on optical coherence tomography, ultrasound biomicroscopy, or slit-lamp exam), which is a preoperative sign of hypertension inside the bag. To date, there are few reports with Zepto capsulotomy, and there is no strong evidence that femto capsulotomy is safer than manual CCC for intumescent white cataracts.

Q3.2 What would you do now?

|

Commence phaco

|

16.7%

|

|

Convert to a can-opener capsulotomy, then start phaco

|

50.7%

|

|

Prechop with the miLOOP, then perform phaco

|

4.6%

|

|

Convert to a manual ECCE

|

27.7%

|

|

Abort surgery and refer the patient

|

0.4%

|

Rosa Braga-Mele When the anterior capsule splits, as it did in this case, it is sometimes difficult to remain calm and proceed in an organized manner. In fact, the first instinct is to do the most straightforward thing … either abort the case and refer or convert to manual ECCE (as chosen by nearly 28% of the audience) if one does not feel comfortable proceeding with phaco.

More than 50% of the audience would have converted to a can-opener capsulotomy and then commenced phaco. However, this could lead to more radial tears and issues with nuclear loss into the vitreous. I chose to begin phaco with the anterior capsule split as it was—but with a twist. I used a dispersive OVD throughout the case to help maintain the pressure in the eye and the structural integrity of the anterior chamber and the capsular bag, with the hope of minimizing the risk of the tear propagating posteriorly to the posterior capsule. I also removed the nucleus in its entirety from the capsular bag and used the iris as a scaffold, as I slowly phacoed the nucleus from the edge without breaking or chopping it into smaller pieces. (That way, if the bag was not intact, there would be less risk of pieces dropping posteriorly.) My most significant pearl for my colleagues is to go slow and never let the eye decompress. Maintaining a cool demeanor and a safe environment is key to getting a good outcome.

|

|

CASE 3. The anterior capsule split when the patient coughed.

|

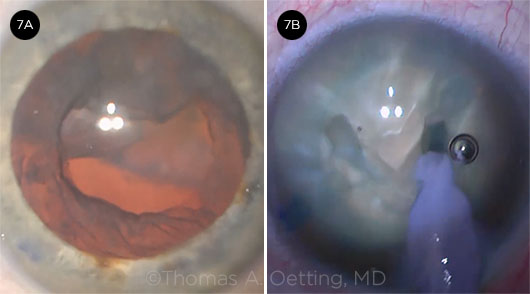

Case 4: My Bipolar Presentation

Kendall Donaldson presented her case of a posterior polar cataract. The femtosecond laser was used first to create the anterior capsulotomy and then to perform grid pattern nuclear fragmentation with a 500-μm safety zone. A large posterior capsular defect was noted nasally. The temporal subincisional heminucleus was still present. (Video.)

Q4.1 What is your surgical preference for a posterior polar cataract?

| Femtosecond laser–assisted cataract surgery (FLACS) for both capsulotomy and fragmentation |

12.4%

|

| FLACS for capsulotomy only |

3.8%

|

|

Manual phaco (I don’t ever use FLACS)

|

70.0%

|

| Manual phaco (I otherwise use FLACS, but not here) |

11.7%

|

|

I refer these cases

|

2.1%

|

Bonnie Henderson I have found that not all posterior polar cataracts behave the same way. In some cases, the posterior capsule is intact but thinner and more fragile. In others, there is a frank defect in the capsule. Even in those cases with a defect, some openings are circular, with strong fibrotic borders that can often withstand the tugging/pulling associated with lens removal. In these cases, the defect does not extend into a tear. However, it is prudent to prepare for every posterior polar cataract case as if a capsular tear can occur. I recommend avoiding hydrodissection and proceeding with hydrodelination to mobilize and remove the inner nuclear core before carefully removing the epinucleus and cortex. Using a dispersive OVD to “plug” the hole in the posterior capsule is also useful to keep the vitreous in a posterior position.

The management of a posterior polar cataract can be challenging because of this unpredictability of the posterior capsule. Because the use of a femtosecond laser creates air bubbles that can build up pressure in a closed eye, I agree with 81.7% of the audience that a manual approach in this case would have been better. Although some surgeons may argue that the use of the femtosecond laser can ensure a continuous anterior capsulotomy and successful lens fragmentation, the difficulty in managing a posterior polar cataract does not lie in these steps. Instead, the difficulty is removing the lens in the face of a capsular defect, which is not made safer using a laser.

Q4.2 How would you remove the remaining heminucleus in the presence of this large posterior capsular defect?

|

Cautiously resume phaco in the bag

|

5.5%

|

|

Attempt to use the I/A tip to aspirate the remaining nucleus

|

1.7%

|

|

Elevate the nucleus into the anterior chamber, then perform phaco

|

50.0%

|

|

Elevate the nucleus into the anterior chamber and phaco over an IOL scaffold

|

41.1%

|

|

Convert to manual extraction of the nucleus

|

1.7%

|

Kendall Donaldson In the case of a posterior polar cataract, the lens is generally not very dense aside from the central posterior core, so the remainder of the lens should require very little phaco energy to remove in its entirety. In this case, the vitreous had not yet prolapsed, so dispersive OVD was used as a tool to prevent the vitreous from shifting forward. I turned to the audience’s preferred strategy (the third choice), and I used a Drysdale spatula to gently lift the remaining lens material into the anterior chamber. Low bottle height, high vacuum, and full occlusion of the nuclear material with the phaco tip was maintained at all times. Despite my best efforts, vitreous prolapse did occur, and I had to do an anterior vitrectomy. Ideally, the vitrectomy should be done through the pars plana or through a new wound after suturing the primary wound with 10-0 nylon. I also like the idea of an IOL scaffold (the fourth option). I would still try to remove more of the lens material before placing the IOL, so as not to capture lens material in the eye. With so little of the capsular bag intact, reverse optic capture (ROC) would be difficult, especially if the capsulotomy is on the larger side (larger than the optic).

|

|

CASE 4. This posterior polar cataract case involved a large posterior capsular defect.

|

Case 5: Battle Royale: Femto Versus Nucleus

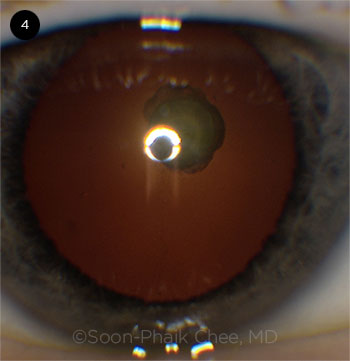

Soon-Phaik Chee’s case involved an 80-year-old patient with an ultrabrunescent rock-hard cataract with a 5.9-mm lens thickness. The femtosecond laser was first used to successfully complete a 5.5-mm anterior capsulotomy. The patient moved during the femtosecond laser nuclear fragmentation, causing the laser firing to abort. When the patient was finally positioned beneath the operating microscope, one-half of the nucleus could be seen prolapsing through the pupil. (Video.)

Q5.1 What would you do now that the lens is prolapsing into the anterior chamber?

| Phaco after repositing the nucleus into the bag |

32.9%

|

| Phaco after prolapsing the nucleus into the anterior chamber |

45.9%

|

|

Manual ECCE (large incision)

|

12.0%

|

| Small-incision manual ECCE (e.g., with miLOOP) |

7.1%

|

|

Abort and refer

|

2.1%

|

Soon-Phaik Chee One pole of this thick brunescent nucleus prolapsed into the anterior chamber following excessive gas formation, lifting the partially fragmented nucleus against an incomplete femto capsulotomy and leading to an anterior capsular rip. This was certainly a challenging situation, and it is no surprise that 2.1% of respondents voted to abort surgery and refer the case on. The largest percentage of the audience voted to phaco after prolapsing the nucleus into the anterior chamber. Bearing in mind the nuclear density and thickness, this would have been technically difficult due to the limited space available in the anterior chamber for manipulating this huge rock, inevitably resulting in significant endothelial cell loss. The option to convert from phaco to large- or small-incision ECCE was the choice of almost 20% of attendees. This option avoids the risk of a dropped nucleus and is perhaps associated with a smaller risk of posterior capsular rupture, but it requires a larger incision.

I decided to proceed with phaco after repositing the nucleus into the capsular bag, which was the choice of a third of the attendees. Faced with the unforeseen, I stained the capsule with capsular dye from the side port to visualize the capsulotomy. The nucleus was gently reposited into the capsular bag using the viscoelastic cannula, releasing the trapped gas bubbles from behind the tilted nucleus. After the anterior capsular rip was identified, phacoemulsification without hydrodissection was started with reduced parameters, using an in-situ chop technique. The lateral separation of nuclear fragments was performed at a location away from the anterior capsular rip to avoid extending the tear posteriorly. It was tedious and difficult to completely separate the fragments, despite the partial femto-fragmentation, as the nucleus was thick and leathery. Rotation of the nucleus was executed carefully about its central axis in order to minimize its lateral movement. The nucleus wobbled during the procedure, suggesting a lack of posterior support, but the fragments continued to swirl around normally.

Finally, an intact thin cushion of cortex covering the posterior capsule was bared. This defined layer was likely to be a result of the 500-μm PC femtosecond laser offset. The anterior chamber was maintained by injecting dispersive OVD before removing instruments from the eye. Coaxial irrigation and aspiration of cortical material was initiated, exposing a wide capsular rip that extended from the anterior capsular tear across the posterior capsule, leaving the anterior vitreous face intact.

CASE 5 CONCLUSION: After the prolapsed nucleus was displaced posteriorly, a radial anterior capsulotomy tear could be seen extending to the equator. The nucleus was manually chopped and removed with phaco—and at this point, the radial anterior capsular tear could be seen extending into a large tear across the entire posterior capsule. Cortex was removed without vitreous prolapse or any need to perform an anterior vitrectomy.

Q5.2 What IOL would you implant at this point?

|

An iris-claw or AC IOL

|

5.9%

|

|

A three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus (no suture)

|

84.4%

|

|

An iris- or scleral-sutured three-piece PC IOL

|

7.5%

|

|

Glued intrascleral haptic fixation (ISHF) of a PC IOL

|

0.6%

|

|

Yamane ISHF of a PC IOL

|

1.7%

|

Edward Holland In the situation of an anterior capsular tear extending into the posterior capsule, the surgeon must assess the stability of the anterior capsule. If there is adequate anterior capsular support, a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus is definitely the procedure of choice. This technique was far and away the one favored by the audience. With an adequate anterior capsule, there is no need for the more complex fixation procedures listed above.

If, however, the anterior and posterior capsular tears are extensive and the IOL needs fixation, then the surgeon should be equipped to perform additional steps to secure the IOL. The most common choice would be an iris- or scleral-sutured three-piece PC IOL, and that was the second choice favored by the audience. The sutured three-piece PC IOL is the favored fixation method utilized, and it has excellent results. Newer techniques, such as the glued ISHF and the Yamane ISHF, are innovative and avoid fixation sutures. However, most surgeons do not have experience with these methods.

|

|

CASE 5. One pole of the nucleus prolapsed into the anterior chamber

|

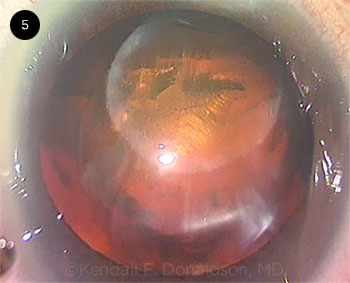

Case 6: I Could Use More Support

Sumitra Khandelwal presented a case of a 52-year-old uveitis patient with a unilateral white cataract. This eye had previously undergone two pars plana vitrectomies and had a history of cystoid macular edema (CME). After trypan blue staining, a small-diameter capsulorrhexis was completed. In the course of divide-and-conquer phaco, the capsular bag became increasingly mobile. After Dr. Khandelwal withdrew the phaco tip for inspection, the entire subincisional pole of the lens prolapsed into the anterior chamber due to severe zonulopathy. (Video.)

Q6.1 Now that the subincisional lens has prolapsed into the anterior chamber because of severe zonulopathy, what would you do next?

| Reposit the lens posteriorly with OVD, then resume phaco |

23.8%

|

| Insert a lens scaffold (e.g., IOL) and resume phaco |

3.6%

|

|

Convert to a manual ECCE (by extending the corneal incision)

|

33.9%

|

| Convert to a manual ECCE (via a separate new incision) |

31.8%

|

|

Abort the surgery and refer the patient

|

6.9%

|

Sumitra Khandelwal This was a tough situation because the whole capsular bag–IOL complex prolapsed into the anterior chamber, risking the lens falling to the back with typical approaches. Much of the audience response reflects individual comfort levels, as this is not an ideal case in which to try something new. I resumed phaco, taking care to prevent the lens from falling posteriorly. The scaffold technique would only really work if there was a posterior capsule or the surgeon chose scleral fixation, but likely this is not the best choice at this time. Conversion to an ECCE—or, in this case, an intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE)—would likely be the best option for anyone who is unfamiliar with using capsule retractors. The downside would be a large incision and the risk of retinal detachment; however, the risk of detachment reported with ICCE is based on normal zonules requiring cryotherapy to break them and vitreous prolapse. This patient is postvitrectomy, so the latter is not an issue.

CASE 6 CONCLUSION: After Dr. Khandelwal reposited the capsular bag posteriorly with OVD, she supported the capsular bag with nylon iris retractors (capsule retractors were not available). However, the capsulorrhexis tore when the phaco tip was inserted. She successfully removed the nucleus without any posterior capsular rupture.

Q6.2 What IOL fixation method would you use with a radially torn anterior capsule, a possible posterior capsular tear, and severe zonulopathy in this postvitrectomized eye with a history of CME?

|

An iris-claw or AC IOL

|

16.2%

|

|

A three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus (no suture)

|

50.0%

|

|

Iris- or scleral-sutured PC IOL

|

20.3%

|

|

Glued ISHF of a PC IOL

|

4.9%

|

|

Yamane ISHF of a PC IOL

|

8.6%

|

Rob Weinstock The audience response to this question is very telling. Half the respondents felt comfortable placing a three-piece lens in the sulcus space despite the zonular instability and the tear in the anterior and posterior capsules. This is a bit surprising since the audience clearly saw at least half of the capsule tilted up and floating in the anterior chamber at the start of the case. The fact that the inferior zonules seem to be intact may be the reason these surgeons felt confident that a lens would be stable in the sulcus. My concern would be that the entire capsule and zonules are not supportive enough, and the IOL could decenter or even dislocate into the vitreous with time.

The other half of respondents chose to do some type of more stable IOL fixation, which would be my preference as well. Surprisingly, most chose either an AC IOL or an iris- or scleral-sutured IOL, while only 9% chose the Yamane technique. This may represent the fact that many surgeons have not been trained or are not comfortable yet with this elegant but novel IOL fixation method and, therefore, prefer a more traditional and practiced technique.

Sumitra Khandelwal In a case with greater than 4 clock-hours of poor zonules, the surgeon can utilize CTRs and segments, but we are unable to do that in the case of an anterior capsular tear. It’s best for the surgeon to do what is most comfortable for him or her. It is surprising that 50% of the audience picked a PC IOL in the sulcus without a suture. Given the combination of diffuse zonules and the anterior capsular tear, the sulcus is not a stable place for the IOL. The IOL will likely fall to the vitreous, if not during surgery then shortly postoperatively. If the surgeon is not comfortable with iris or scleral fixation, then an AC IOL or aphakia is the best option, as a posterior dislocation of the IOL will require retinal surgery and involve possible additional complications.

An iris- or a scleral-fixated lens could be an excellent option. Again, the choice of technique depends on the surgeon’s comfort level. In general, I avoid iris fixation in the setting of history of vitrectomy because of the risk of pseudophacodonesis. However, in this case, there is some posterior capsular support. I also avoid it in cases with a history of uveitis because iritis often occurs, so perhaps scleral fixation is best. Surgeons can choose the option that is best in their hands.

A well-sized AC IOL is always a great choice; several studies have found good outcomes in complex cases, and even in eyes with uveitis. The relatively young age of the patient is concerning for long-term complications, but an endothelial cell count and an IOL exchange can always be performed later. Again, scleral fixation is likely the best option assuming the surgeon is comfortable with this technique, which is why we made that choice.

|

|

CASE 6. In this case of a unilateral white cataract (6A), the capsular bag–IOL complex prolapsed into the anterior chamber (6B). Although the capsular bag was supported by iris retractors (6C), the capsulorrhexis tore when the phaco tip was inserted (6D).

|

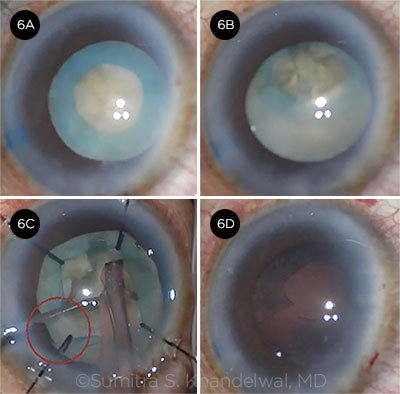

Case 7: Getting Shot Down

In this case presented by Daniel Terveen, Tom Oetting started what he thought would be a routine cataract surgery. The patient had been treated for age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with a series of intravitreal injections over several years. After an uneventful capsulorrhexis and hydrodissection of the lens, the nucleus became excessively mobile during phaco. As the nucleus was rotated, it started to descend posteriorly through a posterior capsular defect (Fig. 7). (Video.)

Q7.1 What would you do next once the nucleus starts to sink posteriorly?

| Try posterior assisted levitation (PAL) to levitate it anteriorly |

26.9%

|

| Urgently summon a vitreoretinal colleague to the OR |

18.0%

|

|

Leave the nucleus and leave the eye aphakic

|

8.2%

|

| Leave the nucleus and implant a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus |

40.1%

|

|

Leave the nucleus and implant a one-piece PC IOL in the sulcus using ROC

|

6.8%

|

Roger Zaldivar These cases represent a real challenge to a surgeon’s ego, and the most difficult decision involves setting limits in order to avoid compromising the patient’s safety. Once the nucleus starts to sink posteriorly, we like to keep things simple by removing residual cortical material, performing an anterior vitrectomy, and placing a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus. Performing a pars plana vitrectomy to remove the fallen nucleus can take place in a second attempt, usually two days later.

Daniel Terveen Dr. Oetting did as the audience suggested by removing residual cortical material and performing an anterior vitrectomy aided by preservative-free triamcinolone. We placed an MA50 IOL (Alcon) initially in the sulcus and then positioned just the optic into the bag, which is a very stable configuration. A few days later the patient had a pars plana vitrectomy to remove the fallen nucleus.1

Q7.2 What do you think was the most likely cause of the early posterior capsular tear in this case?

|

Capsular block with hydrodissection

|

40.1%

|

|

Chopping too aggressively

|

17.0%

|

|

Rotating the nucleus too aggressively

|

17.4%

|

|

Postocclusion surge

|

4.3%

|

|

Occult posterior capsular defect

|

21.3%

|

Daniel Terveen Several interesting studies have reported that patients who have a history of intravitreal injections are two to three times more likely to experience posterior capsular rupture during cataract surgery. These studies suggest that iatrogenic trauma from the injections may have increased both the risk of loss of lens material into the posterior chamber and the risk of a capsular tear. A V-groove nucleofractis technique can be used when you do not want to do hydrodissection or lens rotation, as in cases of posterior polar cataract, or when you suspect posterior capsular injury—e.g., after pars plana vitrectomy2 or, as in this case, following intravitreal injections (Fig. 7B).

___________________________

1 www.facebook.com/cataract.surgery/videos/10154988848396868/. Accessed Dec. 5, 2018.

2 webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/239-post-vit-cataract-surgery.htm. Accessed Dec. 5, 2018.

|

|

CASE 7. (7A) The lens fell early in the case. (7B) A V-groove nucleofractis technique was used to eliminate the need for hydrodissection.

|

Case 8: Nothing Wrong With LRIs

Elizabeth Yeu’s case involved a 72-year-old patient with axial myopia and 2.5 D of with-the-rule astigmatism. A toric IOL was planned; after a femtosecond laser capsulotomy and nuclear fragmentation, the nucleus was removed. However, during cortical cleanup, a large posterior capsular rent was created by the I/A tip. Vitreous prolapse was avoided. (Video.)

Q8.1 What IOL would you implant in this case?

| A three-piece spherical PC IOL in the sulcus (manage astigmatism with LASIK) |

39.0%

|

| A three-piece spherical PC IOL, plus astigmatic keratotomy (AK) |

30.5%

|

|

Place a one-piece toric IOL in the sulcus with CCC/optic capture

|

12.5%

|

| Place a one-piece toric IOL in the bag with ROC |

17.4%

|

|

Leave aphakic and refer the patient

|

0.7%

|

Eric Donnenfeld This patient has 2.5 D of preoperative astigmatism and is a candidate for a toric IOL—and now has a large posterior capsular tear. Although there are several alternatives to consider for managing this complication, the overriding goal should be to choose the procedure that provides the safest outcome for the patient, and that procedure is very surgeon-dependent. Because all toric IOLs in the United States require placement in the capsular bag, if the surgeon feels comfortable with this approach, a toric IOL with primary or reverse optic capture can be considered. It does, however, entail some risk.

The audience overwhelmingly suggested a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus followed by either LASIK or AK. I agree that this is the safest approach. I would perform LASIK, which is more precise and is less likely to result in irregular astigmatism.

Elizabeth Yeu My video demonstrated the option of carefully aligning the toric IOL that is tucked into the capsular bag in a controlled posterior capsular rent with ROC (in which the haptics are in the capsular bag and the optic is prolapsed anteriorly to sit in front of the anterior capsulotomy). Understandably, however, this is not the choice of the audience majority.

Anecdotally, I have found this to work nicely, but I will consider it only in axial myopes who have a well-centered approximately 5-mm capsulotomy without any complications that would necessitate further surgery (i.e., lens fragment in vitreous). The IOL should be calculated for sulcus placement if ROC is performed.

I do agree that a conservative approach of a three-piece IOL injected into the sulcus, ideally combined with optic capture to prevent any iris chafing and recurrent iritis, is an excellent approach any time the posterior capsule is compromised. The corneal astigmatism can be reduced intraoperatively with AK or postoperatively with excimer laser, AK, or spectacles. Modern one-piece IOLs should never be placed into the sulcus, as a form of uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome will result from the chafing of the haptics themselves against the posterior iris, even if the optic is captured.

|

|

KELMAN LECTURE. Robert J. Cionni, MD, was the 2018 Charles D. Kelman lecturer. He is shown here with Drs. Chang (left) and Weikert (right).

|

Case 9: Shifting Fortunes

Bill Wiley’s patient was an ophthalmologist with pseudoexfoliation, a small pupil, and primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). After Dr. Wiley inserted a Malyugin ring, the capsulorrhexis and hydrodissection were completed. Zonulopathy was noted during divide-and-conquer phaco, and Dr. Wiley paused to insert capsule retractors. The cortex was successfully removed despite severe circumferential zonulopathy, but an anterior capsular tear was noted in the region of one of the capsule retractors. (Video.)

Q9.1 At this point, what IOL fixation method would you employ?

| Place a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus |

55.2%

|

| Place a one-piece PC IOL in the bag |

26.9%

|

|

Scleral fixate the haptics of a three-piece PC IOL

|

11.1%

|

| Iris suture the haptics of a three-piece PC IOL |

3.7%

|

|

Use an AC or iris-claw IOL

|

3.1%

|

Bill Wiley During the extraction of the complicated cataract, an anterior capsular rent developed, which further complicated the surgery. I believe the rent was caused by the capsule support hook, which might have caused undue stress on the anterior capsule during the insertion of the I/A tip or the phase fusion. (It’s important to note that the tension of the hooks should be adjusted after the anterior chamber is manually filled with balanced salt solution [BSS].)

This anterior capsular rent in a bag with loose zonules presented me with a critical decision: Where should the lens be placed? The audience chose a three-piece IOL in the sulcus. In general, I believe this is a good decision, and it is ultimately what I chose to do. However, in addition to placing the lens in the sulcus, I decided to further support the capsule-bag complex by placing a CTR in the bag. This maneuver can cause stress on the bag, and it introduces the risk of further expanding the anterior capsular tear. To help prevent that, I used a suture in the CTR to help with insertion and to give an option to remove the ring if I felt that it was not providing support.

After I inserted the CTR into the bag, I noted that the anterior capsular tear was stable and had not extended, and the ring seemed to give the needed support. At that point I considered placing a lens in the now-stabilized bag, but I opted for sulcus placement instead. At the conclusion of the case, the lens appeared secure; it was centered and stable in the sulcus on top of the bag and CTR. Unfortunately, the next day, the lens was subluxated inferiorly even though the bag appeared stable. I believe the lens slipped past an area of absent zonules, resulting in the malpositioned optic.

CASE 9 CONCLUSION: After Dr. Wiley implanted a CTR in the bag, he implanted a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus without any supplemental haptic suture or scleral fixation. On postoperative day 1, however, there was a major “sunset” inferior subluxation of the PC IOL.

Q9.2 How would you manage this IOL, which is already subluxated one day after surgery?

|

Iris suture the existing PC IOL

|

18.2%

|

|

Scleral fixate the existing PC IOL

|

40.2%

|

|

Perform an IOL exchange with an AC or iris-claw IOL

|

7.4%

|

|

Exchange for an Akreos IOL (Bausch + Lomb) with Gore-Tex scleral fixation

|

4.4%

|

|

Refer the patient

|

29.7%

|

Alan Crandall Since the CTR is still in the eye, that device should be removed. Looking at the possibilities, the first (iris fixation using the IOL) would be feasible, as the retina associate is doing a vitrectomy.

I prefer not to use iris fixation, as there can be significant pseudophacodonesis (which can lead to UGH and recurrent inflammation), but if an anterior vitrectomy is all that is needed, it would be a reasonable choice.

With regard to an IOL exchange with an AC IOL or the iris-claw IOL, I prefer not to use AC IOLs in patients this young because of potential downstream problems (glaucoma, peripheral anterior synechiae, and/or ovalization of iris). The iris-claw lens would be a reasonable choice; however, it is not yet FDA approved. As for an IOL exchange with the Akreos, using four-point scleral fixation with Gore-Tex sutures: This can be an elegant procedure, and it is one I have used and like. My one caveat is that the lens is made of a hydrophilic acrylic material. Some of these complicated eyes may need a DSAEK procedure—and the air bubble could cause the anterior IOL surface to opacify. (Bausch + Lomb is planning to develop a version with a hydrophobic acrylic material, which would not opacify with air.)

Finally, the option of scleral fixation with the existing lens would be my choice in this setting. One could use the Yamane technique or any version of a glued IOL.1-3

Bill Wiley Nearly one-third of the audience recommended referral. I took this path, and I referred the patient to a retina specialist. My colleague performed a vitrectomy with a lens exchange, using an Akreos IOL (Bausch + Lomb), which allowed for four-point fixation with Gore-Tex sutures. This created a very stable fixation and—because of the patient’s underlying POAG—was preferable to the choice of iris fixation or an AC IOL.

___________________________

1 Yamane S et al. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(8):1136-1142.

2 Gabor SC, Pavilidis MM. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(11):1851-1854.

3 Agarwal A et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(9):1433-1438.

Case 10: When Routine Becomes Not-so-Routine

Kerry Solomon presented his case of a 29-year-old patient who had been continuously unhappy with her uncorrected near vision following previous implantation of a distance monofocal acrylic IOL in her right eye. Both eyes were very blurry with 20/70 best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in her right eye due to a secondary membrane and 20/50 BCVA in her left eye (due to cataract). She wanted to be spectacle independent, if possible. (Video.)

Q10.1 What would you recommend for this patient?

| YAG the right eye, then implant a monofocal IOL (mini or full monovision) in the left eye |

36.5%

|

| YAG the right eye, then implant an extended depth of focus (EDOF) or monofocal IOL in the left eye |

23.6%

|

|

Implant an EDOF or a monofocal IOL in the left eye, then address the right eye

|

22.4%

|

| Implant a monofocal IOL (mini or full monovision) in the left eye, then address the right eye |

5.7%

|

|

Exchange the monofocal IOL in the right eye for an EDOF or a monofocal IOL in that eye

|

8.7%

|

|

Refer this patient elsewhere

|

3.0%

|

Thomas Kohnen Young adult cataract patients have often been excluded from receiving multifocal IOLs. However, these patients can now benefit from new IOL technology and modern IOL power estimations, as outcomes are now so much better. As this patient is unhappy with the near visual acuity after monofocal IOL implantation, this should be best addressed with an IOL exchange or IOL addition (add-on technology).

The question of which eye should be treated first and which IOL should be chosen is not an easy one to answer. If we assume the right eye is the dominant one, one option would be to perform an exchange with an EDOF IOL in the right eye and a trifocal IOL for near vision in the left eye. The second option could be to use panfocal (tri-/quadrifocal) IOLs in both eyes. With the progress we have made over the last five years with these IOLs, I would feel comfortable exchanging the monofocal IOL for a tri-/quadrifocal IOL. The secondary cataract can be addressed intraoperatively with a posterior capsular opening, which would provide the patient with a clear view directly after the intervention. However, the latter treatment, when performed with an Nd:YAG laser, would enable an easier IOL exchange in the future.

A third option would be to implant a trifocal add-on IOL, which leaves the monofocal IOL in place. In addition, the procedure is reversible. Posterior capsular opacification in this case can be treated later with a Nd:YAG laser. If the patient is happy with the outcome of the right eye, the left eye could be treated immediately after with a tri-/quadrifocal IOL. Overall, in our experience, patients who have received these IOLs are happier with near visual acuity than are those who have received EDOF IOLs with a very similar optical phenomena effect. As a result, I prefer tri-/quadrifocal IOLs for those patients who really want to be spectacle independent.

My final thought is on IOL calculation. As we know the outcome of the first eye, we would take the IOL power of the right eye implant into consideration in case of an IOL exchange. Add-on IOL power calculation is based on the postoperative refractive outcome; for the second eye, we would choose one of the modern IOL calculation formulas, such as Barrett Universal II or Hill-RBF.

CASE 10 CONCLUSION: Dr. Solomon did cataract surgery first in the left eye and implanted an EDOF IOL. The patient was extremely happy with the uncorrected vision and requested that the monofocal IOL in her right eye be explanted and exchanged for an EDOF IOL. She still wanted better uncorrected near vision, and Dr. Solomon planned an IOL exchange with a multifocal IOL. The single-piece acrylic IOL was dissected free from the capsular bag and then was bisected with an IOL cutter prior to removal. As the posterior capsule was vacuumed with the I/A tip, a large posterior capsular tear was discovered.

Q10.2 What IOL would you implant, given the presence of this large posterior capsular tear?

|

Place a one-piece multifocal IOL in the bag

|

8.5%

|

|

Place a one-piece multifocal IOL using ROC

|

10.5%

|

|

Place a three-piece multifocal IOL in the sulcus with CCC/optic capture

|

50.8%

|

|

Place a three-piece monofocal IOL in the sulcus

|

29.8%

|

|

Abort the surgery and refer the patient

|

0.4%

|

Kerry Solomon This 29-year-old woman with posterior subcapsular cataracts had a hyperopic outcome after having a monofocal IOL implanted three years earlier in her first eye. She was interested in spectacle independence for both distance and near vision, and she had not tolerated monovision in the past. In addition to her BCVA, she had visually significant posterior capsule opacification (PCO) in her previously operated eye and a posterior subcapsular cataract in her fellow eye. She underwent uneventful cataract surgery with an EDOF IOL in the fellow eye. While her distance vision was excellent (20/20), she still wanted better near vision. Subsequently, I performed an IOL exchange of her single-piece acrylic IOL—and discovered an open capsule.

At this point, most of the attendees (51%) chose a three-piece multifocal IOL for sulcus placement and CCC optic capture. This is a very reasonable response, and this strategy would achieve the patient’s goal of improved reading vision with a stronger reading add in a multifocal compared to an EDOF lens. The next largest response (30%) was for a monofocal IOL placed in the sulcus. While this is also a reasonable response, the patient would likely need to continue to use reading glasses. If she were older, this might not be an issue, but at age 29, this would likely be of greater concern. Finally, 19% of attendees would choose a single-piece multifocal.

I chose a single-piece multifocal IOL with ROC. Although the lens centered very well in the capsule without optic capture, capturing the optic may provide a little more security in the short term for centration. The patient has been and will need to be followed for pigment dispersion. To date (eight months postoperatively), none has been detected.

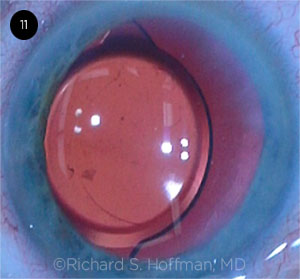

Case 11: Why Don’t You Stay?

In Rich Hoffman’s case, following routine surgery, the intracapsular single-piece acrylic monofocal IOL was discovered to be decentered on postoperative day 1. (Video.)

Q11.1 What would you do for this asymptomatic patient at this point?

| No intervention unless or until the patient becomes symptomatic |

65.4%

|

| Try a miotic to see whether the edge is still exposed |

6.3%

|

|

Return to the OR to surgically reposition the IOL

|

20.3%

|

| Perform an IOL exchange with a three-piece PC IOL in either the bag or the sulcus |

7.7%

|

|

Refer the patient

|

0.3%

|

John Hovanesian As this implant decentration was not discovered until the day after surgery, it is reasonable to wait to assess the patient’s symptoms before deciding on further surgical steps, as 65% of the audience members recommended. However, the significant degree of decentration in this case suggested that the patient would experience symptoms, which did indeed occur. Simply returning to the OR to “reposition” the implant, as suggested by 20% of the audience, is not likely to be a viable option; a single-piece implant with significant decentration usually signals either a peripherally torn capsule with haptic extrusion into the vitreous or a damaged haptic. In this case, with a damaged haptic, the only viable option was to replace the lens.

CASE 11 CONCLUSIONS: The patient was promptly brought back to the OR to surgically reposition the IOL. However, each time the IOL optic was manually centered, it kept migrating within the capsular bag to the same decentered position that it started in.

Q11.2 What would you do next?

|

Leave it alone

|

18.1%

|

|

Insert a CTR

|

21.3%

|

|

Fixate it with ROC through the CCC

|

47.7%

|

|

Exchange it for a three-piece PC IOL in the bag

|

4.2%

|

|

Exchange it for a three-piece PC IOL in the sulcus

|

8.7%

|

Rich Hoffman This single-piece IOL would not center. After several attempts at simple recentration with a Sinskey hook, I decided that there was probably something abnormal about the capsular bag equator that was causing the decentration. At this point, I decided to rotate the IOL 90 degrees, thinking that placing the haptics in a new location within the bag should eliminate the tendency of the IOL to drift nasally. To my surprise, half of one of the haptics was missing, and this was the cause for the perpetual decentration.

Before I discovered the missing haptic, “leaving the IOL alone” was an option, but it’s always difficult leaving a lens in the eye in a suboptimal position. Most of the audience thought that centering and fixating the IOL with ROC was the best choice—and, in general, I think this is a good option other than the small refractive change and eventual onset of PCO. Once the damaged haptic was discovered, I elected to remove it and replace it with a three-piece IOL in the bag. Another single-piece IOL could also have been placed in the bag.

Whenever possible, I believe it is best to try to determine the cause of the decentration. It can result from occult vitreous prolapse, a kinked haptic, or, as in this case, a torn haptic. Once I discovered that the haptic was missing, it was very important to determine if the torn haptic fragment was still in the eye. The last video clip in this presentation demonstrated an old case of corneal decompensation that required a penetrating keratoplasty (before the days of DSAEK and DMEK) several months after a routine IOL exchange. Apparently, after bisecting the IOL to be exchanged, the surgeon left a small sliver of IOL in the eye, and this was ultimately responsible for the endothelial decompensation. If my decentered IOL case had just been “left alone” and a haptic fragment remained in the eye, a catastrophic complication could have occurred. Luckily, the fragment was never injected into the eye; this was confirmed by reviewing the original video and documenting that the IOL was injected without the haptic fragment.

|

|

CASE 11. Each time the IOL optic was manually centered, it migrated.

|

Case 12: Fool Me Once …

Luis Izquierdo presented the case of a 58-year-old patient who has always worn contacts for a large degree of congenital anisometropia. Her goal was to have balanced refraction so that contacts would no longer be necessary. After cataract surgery in her more myopic left eye, she immediately complained that she was unable to see anything on postoperative day 1. A review of the chart revealed that she had received the wrong IOL power—one that would have been correct for her right eye. She required a low-power +4.0 D IOL for her left eye. Dr. Izquierdo explained what had happened and took her back to the OR for an IOL exchange in that eye. (Video.)

Q12.1 What is your preferred method for explanting a single-piece acrylic IOL for an IOL exchange?

| Bisect the lens with an IOL cutter |

49.5%

|

| Cut 90% across the IOL to leave it hinged, and remove it as one piece |

24.8%

|

|

Use the “Pac-Man” method: Excise one quadrant with scissors, then rotate the IOL out

|

18.2%

|

| Use forceps to refold the acrylic IOL inside the eye |

5.3%

|

|

Use another method

|

2.3%

|

Natalie Afshari My preferred method of explanting a single-piece acrylic IOL is to cut the lens with an IOL cutter while supporting it with retinal forceps and then removing it. This could be performed by cutting through 90% of the IOL and then removing it as one piece through the incision (my technique of choice) or bisecting it fully into two pieces and removing each half separately. I agree with the majority of the audience. Folding the IOL inside the eye can be tricky, but it is a nice maneuver if the surgeon has experience with that technique, and it eliminates the risks that come with having a sharp instrument in the eye.

While no major studies have demonstrated the superiority of one technique over another—and there are no studies that directly assess endothelial cell loss with each technique—I feel that cutting the IOL into multiple small pieces or folding the IOL may induce more endothelial damage, as these strategies involve more maneuvering in the anterior chamber. (In these cases, the use of an OVD in the anterior chamber is crucial for endothelial cell protection.) Therefore, although removing the IOL as one piece or bisecting it may be more technically demanding and require the main incision to be enlarged, it could be more endothelial cell–friendly. In the presence of a deep enough anterior chamber, I would also consider inserting the new IOL before explanting the old one so that it could serve as a scaffold and protect the posterior capsule.

CASE 12 CONCLUSION: Dr. Izquierdo explanted the single-piece IOL by first refolding it inside the eye with forceps. When the low-power three-piece IOL was implanted into the capsular bag, the haptic was bent during injection. This resulted in poor intracapsular centration of the IOL, and a posterior capsular tear was also noted. Because of the unusual low power, no backup IOL was available.

Q12.2 At this point, what would you do?

|

Leave the IOL in the bag

|

17.3%

|

|

Leave the IOL but implant a CTR in the bag

|

3.8%

|

|

Position the IOL in the sulcus and suture the haptic to the iris

|

17.3%

|

|

Explant the IOL and leave the eye aphakic

|

43.8%

|

|

Use another method

|

17.8%

|

Luis Izquierdo At this point, my options included leaving the IOL in place to see if some decentration could be tolerated—or explanting it and leaving the patient aphakic. With the low-powered IOL, the patient might have a tolerable amount of hyperopia, or a secondary IOL could be performed later after a replacement IOL was ordered. In this particular case, the patient was already very unhappy that she required a second surgery to exchange the wrong power IOL. As I hated to leave her with anything but a perfect result, I tried a novel approach. Even though the IOL had already unfolded within the eye, what if I could just replace the bent haptic and keep the same optic? I pulled the bent haptic out of the optic while the IOL was still in the eye. I then pulled a haptic off a brand-new IOL (one with a different power), and I was able to dock this into the vacant haptic tunnel within the intraocular optic. The docking was secure, and the IOL was then rotated into the capsular bag with beautiful centration!

Case 13: When Push Comes to Shove

Bob Osher presented a case in which, following routine phaco and cortical cleanup, the single-piece acrylic toric monofocal IOL was inserted upside down. The IOL was flipped within the eye to the proper orientation, but there was some posterior pressure during this maneuver. As the OVD was removed with the I/A tip, the globe became firm and the anterior chamber shallowed due to massive positive pressure. It was difficult to even remove the I/A tip due to flattening of the chamber despite continuing irrigation. (Video.)

Q13.1 What would be your next step?

| Add more retentive OVD via the side port |

33.2%

|

| Start intravenous (IV) mannitol, then add more OVD |

29.8%

|

|

Perform a vitreous tap (e.g., via the pars plana)

|

14.1%

|

| Insert IOL before resuming phaco |

1%

|

|

Abort the surgery in case of a suprachoroidal hemorrhage concern

|

22.0%

|

Bob Osher There are a number of useful steps to prevent unexpected chamber shallowing, especially if it is related to fluid misdirection, which occurs as the infusion during the phaco and I/A follow gravity through the zonules, thus expanding the contents of the vitreous cavity.

I always recommend hydrating the incision before introducing the I/A tip to remove the OVD. After the OVD has been removed and before I withdraw the phaco tip, I will place a cannula on a syringe filled with either BSS or Miochol-E (Bausch + Lomb) through the side port. Then I will kick off the continuous irrigation on my footswitch and simply observe the behavior of the chamber. If it remains deep, I will inject fluid and withdraw the I/A tip before hydrating the incision once again. However, if the lens moves forward and the chamber begins to collapse, I will inject fluid through the side port and keep the I/A tip in place (allowing it to act like a “finger in the dike”) as I depress the footswitch, thus activating irrigation to forcefully deepen the chamber. Mild positive pressure can be managed by injecting fluid with the left hand, withdrawing the I/A tip, and immediately hydrating the incision again. But if the positive pressure appears to be significant, the I/A tip should remain in the incision while the second cannula is exchanged for another syringe containing air.

The injection of air will deepen the chamber and allow the surgeon to withdraw the I/A tip and forcefully hydrate the main incision. The air bubble is both highly effective and cost-efficient. Air has mild endothelial toxicity, so it can be exchanged for either BSS or Miochol-E in small aliquots. But it is difficult to remove air from the corneal dome with a conventional cannula because the distortion of the incision results in loss of fluid. Therefore, I designed a curved cannula with Bausch + Lomb (I receive no royalties), which allows access to the corneal dome, where some of the air is aspirated. The cannula is withdrawn, and fluid is injected through the stab incision. This sequence is repeated several times until most or all the air is removed and replaced with fluid, thus maintaining a deep chamber.

A plurality of surgeons responded that they would add a retentive OVD; however, this does not solve the problem and still has to be removed. Another group recommended starting mannitol, but it takes too long to have any meaningful effect. Performing a vitreous tap will certainly work, although it is unnecessary. The last answer, aborting the case if a suprachoroidal hemorrhage is present, is reasonable, but the surgeon should be able to view the fundus, which can easily be accomplished with the Osher fundus lens (Ocular Instruments; again, no royalties). The urgent use of air is an excellent surgical technique for managing the shallow anterior chamber in fluid misdirection syndrome.

Q13.2 Have you ever experienced anterior chamber shallowing with aqueous misdirection syndrome?

|

Never

|

7.3%

|

|

Possibly, but I didn’t recognize the etiology

|

26.4%

|

|

Once or twice

|

35.3%

|

|

Approximately three to five times

|

18.5%

|

|

More than five times

|

12.5%

|

Marjan Farid Aqueous misdirection—or, more accurately, infusion misdirection—can occur during or at the end of a routine cataract surgery, and it is common enough that most busy cataract surgeons will experience this phenomenon a few times during the course of their career. The audience response supports this, in that approximately 65% of attendees stated that this has happened to them one or more times.

It is important to identify infusion misdirection when it occurs, ensure that the positive posterior pressure and firmness of the globe are not related to a suprachoroidal hemorrhage, and have a directed plan of action for its management. In mild cases, it is possible to reposit any prolapsing iris with a small amount of dense, cohesive OVD, put a suture through the wound, and recheck the pressure in an hour to make sure that it is normalizing. Dr. Osher demonstrated an excellent technique that involved placing an air bubble into the anterior chamber and securing the wound while allowing time for the pressure to normalize, the vitreous to contract, and the eye to stabilize in the postoperative area.

In more severe instances, in which the globe is very dense and the anterior chamber is flat, it is quite reasonable to cut a small-port sclerotomy about 3 mm posterior to the limbus, create a vitrectomy port, and perform a small amount of posterior vitrectomy with no irrigation to break up the anterior hyaloid and deepen the anterior chamber. This requires only one to two seconds of vitrectomy to break the posterior pressure. Of course, it is very important to confirm that the vitrector is in the center of the eye and well visualized behind the IOL before starting the vitrectomy. This technique is very effective at breaking the infusion misdirection, softening the globe, and deepening the anterior chamber.

SPECIAL AWARDS

The following cases were chosen for special awards by audience vote.

Cases 1 to 3: Second City Award

Awarded to the case that required the best use of surgical improvisation.

Rosa Braga-Mele

Cases 4 to 6: Prohibition Award

Awarded to the surgeon who “did the most things that I would not do.”

Soon-Phaik Chee

Cases 7 to 9: Chicago Blues Award

Awarded to the case that was the most upsetting to watch.

Bill Wiley

Cases 10 to 12: Al Capone Award

Awarded to the best case of a surgeon who committed a crime but got away with it.

Luis Izquierdo

Cases 13 to 15: Windy City Award

Awarded to the case “that most blew me away.”

Nicole Fram

Cases 16 to 18: “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” Award

Awarded to the case that required the most endurance.

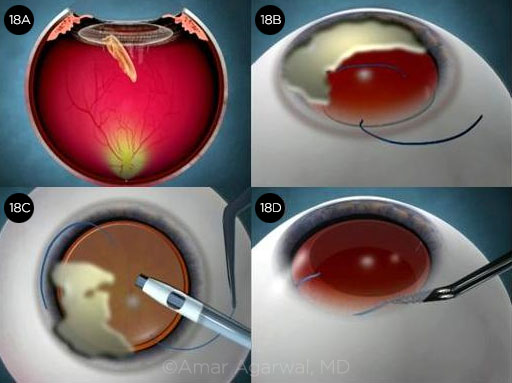

Amar Agarwal

|

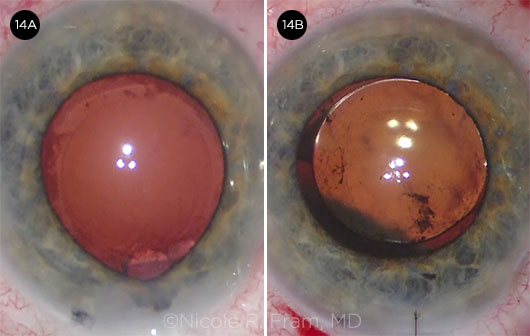

Case 14: Getting Squeezed

In Nicole Fram’s case of a 72-year-old patient with Parkinson disease, the globe became very firm following uncomplicated femtosecond laser capsulotomy, phaco, and cortical cleanup. The anterior chamber was shallowing during I/A, so Dr. Fram switched to bimanual I/A for some remaining subincisional cortex, but the anterior chamber became increasingly shallow. The eye was firm, but the patient reported no pain, and there was no fundus shadow evident against the red reflex. A cohesive OVD was injected in order to implant the IOL, resulting in some partial prolapse of the subincisional iris. (Video.)

Q14.1 What would you do next?

| Start IV mannitol and attempt IOL implantation |

35.4%

|

| Perform a pars plana vitreous tap, then implant the IOL |

37.5%

|

|

Stop surgery, have the patient rest for an hour, then attempt IOL insertion

|

16.5%

|

| Reposit the iris and abort surgery, leaving the eye aphakic |

9.1%

|

|

Leave the iris prolapsed and abort surgery, leaving the eye aphakic

|

1.4%

|

Dick Lindstrom Unexpected shallowing of the anterior chamber with significant positive posterior pressure occurs during cataract surgery in 1% to 2% of procedures. The differential diagnosis includes fluid misdirection syndrome (in which the infusion fluid passes through the zonules and pushes the posterior capsule and iris forward) and the more serious choroidal hemorrhage.

Fluid misdirection syndrome can result in the so-called rock-hard eye syndrome. This can be relieved by removing fluid from the vitreous, as recommended by 37.5% of the audience, using needle aspiration with a 23-gauge needle or pars plana vitreous cutter. I prefer a vitreous cutter but have had success with simple needle vitreous aspiration. It is important to rule out a choroidal hemorrhage before vitreous aspiration, as this maneuver can increase choroidal bleeding and possibly result in direct damage to the retina in the face of a choroidal detachment.

Patients with a choroidal hemorrhage usually have significant pain and loss of red reflex, and the hemorrhage can be seen with intraoperative visualization of the retina. I no longer personally use IV mannitol, but many in the audience have found this useful. It is usually necessary to soften the eye some to be able to reposit prolapsed iris, and a high-molecular-weight cohesive OVD can be helpful along with a miotic applied directly to the prolapsed iris. I never excise prolapsed iris in cataract surgery, but a small peripheral iridotomy can be helpful in some cases. In a difficult case, I do not hesitate to close the wound with sutures and abort the case. I can then check the intraocular pressure (IOP) and examine the patient with the slit lamp and indirect ophthalmoscope 60 minutes later.

In the case of fluid misdirection syndrome, the positive pressure almost always spontaneously resolves, and the patient can be returned to the OR later the same day or the next day for completion of the procedure. In the face of a choroidal hemorrhage, the diagnosis becomes clear, and the patient can be counseled and managed appropriately, usually in collaboration with a retina specialist.

CASE 14 CONCLUSION: A suprachoroidal hemorrhage was diagnosed postoperatively. It eventually resolved without further surgery with an excellent visual outcome (20/20) by one month. The patient was pleased and was eager to undergo surgery in the second eye.

Q14.2 The patient was happy with the first outcome and requested surgery on the second eye. What would you recommend?

|

Advise that he delay or avoid the second surgery due to high risk

|

2.8%

|

|

Refer him elsewhere for the second surgery

|

5.6%

|

|

Do phaco under topical anesthesia

|

24.8%

|

|

Do phaco with retrobulbar block or general anesthesia

|

60.4%

|

|

Do phaco (either the third or fourth choice), but with FLACS

|

6.4%

|

Nicole Fram Significant risk factors for suprachoroidal hemorrhage during cataract surgery include advanced age, hypertension, anticoagulation, glaucoma filtering procedures, penetrating keratoplasty, high myopia, large-incision surgery, and/or a Valsalva maneuver. The pathophysiological mechanism of suprachoroidal hemorrhage involves abrupt hypotony or trauma causing shearing of the short or long posterior ciliary blood arteries or vortex veins in the potential space between the deep sclera and the choroid.

The surgeon who is considering cataract surgery in a patient who has demonstrated the potential for a suprachoroidal hemorrhage in the first eye should take precautions in the second eye. Interestingly, this particular patient had no obvious risk factors. Nonetheless, I avoided all conceivable triggers of IOP fluctuation that might cause hypotony pre-, peri-, and postoperatively. Preoperatively, general anesthesia with paralysis was administered to avoid any potential for squeezing intraoperatively. A retrobulbar block was excluded due to the potential for high and then low surrounding ocular pressure. In addition, FLACS was excluded to avoid any potential for abrupt IOP fluctuations during suction release. Intraoperatively, careful attention was made to ensure that the anterior chamber was stable throughout the procedure by filling with BSS or viscoelastic each time an instrument was removed. This allowed for minimal IOP fluctuation and maximum stability with a normotensive IOP at the conclusion of the case. Postoperatively, special precautions were taken to avoid excessive coughing or Valsalva maneuvers while the patient was waking up from general anesthesia. Fortunately, the patient had an uneventful manual small-incision phacoemulsification and no complications.

If a suprachoroidal hemorrhage had occurred in the second eye and the patient had classic signs of pain and anterior chamber shallowing with a decreased red reflex, the best course of action would have been to close the eye, evaluate the patient postoperatively with a retina colleague to assess the extent of the hemorrhage, and maintain normotensive IOP control to tamponade the hemorrhage. Mannitol or acetazolamide should be given only in the setting of high postoperative IOP, as hypotony is undesirable in the immediate management of suprachoroidal hemorrhages.

|

|

CASE 14. Unexpected shallowing of the anterior chamber (14A) was followed by a suprachoroidal hemorrhage (14B).

|

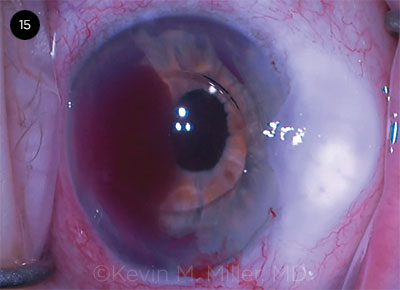

Case 15: My Turn to Turn Red

Kevin Miller’s case involved an 85-year-old patient with bilateral ReSTOR multifocal IOLs and a trabeculectomy in the left eye. The bag-IOL complex in the left eye became dislocated following a car accident. There was a history of pseudoexfoliation, and no CTR was implanted. (Video.)

Q15.1 How would you address this late bag–multifocal IOL dislocation?

| IOL exchange with a scleral-fixated three-piece multifocal ReSTOR |

23.9%

|

| IOL exchange with an iris- or a scleral-sutured monofocal PC IOL |

23.5%

|

|

IOL exchange with ISHF monofocal PC IOL (glued or Yamane)

|

18.2%

|

| IOL exchange with an AC or iris-claw IOL |

13.0%

|

|

Refer this patient

|

21.5%

|

Kevin Miller It’s interesting to note that there was absolutely no audience consensus on the best way to proceed with this bag–multifocal IOL dislocation. Achieving perfect pupil centration when securing a lens to the sclera is difficult. If the entire central ring of a diffractive optic is not completely within the pupil, quality of vision suffers. About a fifth of respondents would refer the patient, which is always a reasonable choice. There was an almost even split between iris or scleral suture fixation of a monofocal lens and intrascleral haptic fixation. Both of these approaches would normally place the patient at higher risk of bleeding than the approach I took, which was to exchange the ReSTOR for an AC IOL. I have found that AC IOL implantation is quick and easy and, if sized appropriately, safe for the corneal endothelium, especially in an older patient.

An additional benefit of AC lenses is that they do not dislocate. There are no sutures to break and no haptics to wiggle their way out of scleral tunnels. Unfortunately, the quest to perfectly position the haptics led to an inadvertent iris root tear and pesky intraoperative bleeding. Maybe the audience was right!

CASE 15 CONCLUSION: An IOL exchange was performed, during which the bag-IOL complex was explanted and an anterior limbal vitrectomy was performed. An AC IOL was implanted. While Dr. Miller was maneuvering the IOL away from the incision, significant bleeding commenced from the iris root adjacent to the rotated haptic.

Q15.2 Would you stop blood thinners prior to performing a vitrectomy and an IOL exchange?

|

Would not stop any blood thinners

|

28.7%

|

|

Aspirin would be okay, but I would stop warfarin

|

17.0%

|

|

Would stop all blood thinners, including aspirin

|

33.6%

|

|

Yes for an AC IOL; no for a PC IOL

|

9.8%

|

|

Would refer these patients

|

10.9%

|

Sam Masket In general terms, I am comfortable leaving patients on anticoagulant therapy for routine cataract surgery, as this is, or should be, an avascular procedure. That said, surgery is not truly “routine” until it is completed. With warfarin therapy I prefer that the INR (international normalized ratio) be no higher than 3.2.

However, in consideration of the more involved surgery for IOL exchange, including multiple pars plana entries, vitrectomy, and potential scleral fixation of the IOL, my comfort zone changes. In this instance, I prefer that the patient discontinue use of all anticoagulant agents, as the procedure invades vascular tissue and there is a potential for hypotony early after surgery. The latter increases the risk for significant ocular hemorrhage.

It is prudent to be in contact with the patient’s general physician and coordinate plans for stopping and starting anticoagulants, as some cases will require use of heparin or similar agents in the perioperative period, while others may be safe off medication for prolonged periods, varying with the underlying indication for anticoagulant therapy.

Interestingly, the audience response showed no clear trend, as 29% would not—and 34% would—stop blood thinners for the complex case at hand.

|

|

CASE 15. An iris root hemorrhage occurred while an AC IOL was being dialed into final position.

|

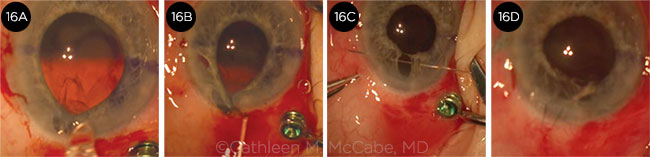

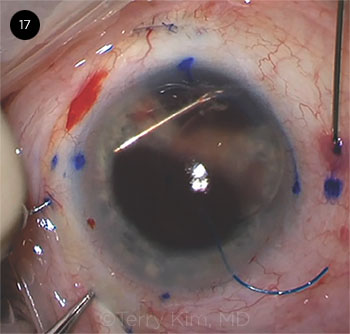

Case 16: Who Knows What Evil Lurks?