Download PDF

From posterior polar cataract and temporal negative dysphotopsia to phaco in uveitis and glaucoma patients, the 2016 Cataract Spotlight session covered much ground. See the audience poll responses, and read fresh commentary from the experts.

This past October, the 15th annual Spotlight on Cataract Surgery Symposium at the Academy’s annual meeting was entitled “Complicated Phaco Cases—My Top 5 Pearls.” Cochaired by Mitchell Weikert, MD, and myself, this 4-hour symposium focused on challenging cataract and IOL cases.

During this symposium, 16 international cataract experts were each given 7 minutes to highlight their 5 best pearls for a specific type of challenging case. A shot clock timer was displayed to ensure that the take-home points were summarized in a concise and concentrated manner. Amazingly, not a single speaker exceeded the 7-minute limit.

The topics included posterior polar cataract, rock-hard nuclei, mature white lenses, anterior vitrectomy, post-LASIK eyes, temporal negative dysphotopsia, and delayed bag-IOL dislocation. In addition, the presentations covered phaco in patients with uveitis, Fuchs dystrophy, intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS) and small pupils, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, pseudoexfoliation with weak zonules, high myopia, and high hyperopia with a crowded anterior segment. The final topic was medicolegal considerations with unhappy cataract patients.

A rotating panel of additional experts then shared their own pearls and strategies for these challenging cases in a free-flowing discussion. Finally, using electronic response pads, audience members were able to register their own opinions and preferences for each of the 16 subject areas. (Register your response to the sample poll question immediately below this introduction. Then scroll to Case 13 to see how your colleagues at the spotlight symposium responded.)

Roger Steinert concluded the spotlight symposium by delivering the 12th annual AAO Charles Kelman Lecture, “Cataract/Refractive Surgery: The Next Big Thing?” in which he presented 3 exciting new refractive technologies that he is working on—the Raindrop inlay, the LensGen accommodating IOL, and refractive index shaping of lenses in vivo.

|

|

KELMAN LECTURE. Roger Steinert, MD, was the 2016 Charles D. Kelman lecturer. He is shown here with Drs. Chang (left) and Weikert (right).

|

This EyeNet article reports the results of the 32 audience response questions, along with written commentary from the symposium presenters and panelists. Because of the anonymous nature of this polling method, the audience opinions are always candid, and these were discussed in real time during the symposium by our panelists. The Spotlight on Cataract Surgery Symposium also annually attracts a virtual audience that watches the program online in real time and is able to respond to the audience questions along with the live audience. A recording of the entire symposium can be obtained at AAO Meetings on Demand (see below).

—David F. Chang, MD

Cataract Spotlight Program Cochairman

Scroll to Case 13 to see how your colleagues at the spotlight symposium responded.

Case 1: Phaco With Uveitis

Q1.1 With a history of severe uveitis, what is your preferred route for adjunct postop steroid?

| Topical only |

11.1%

|

| Periocular injection |

20.0%

|

|

Intraocular injection

|

5.5%

|

| Oral |

9.4%

|

|

Oral + #1 or #2

|

54.0%

|

Eric Donnenfeld Phacoemulsification in patients with uveitis is among the most challenging cataract surgeries we perform. The overwhelming consideration is to have an eye that is as quiet as possible preoperatively, to perform atraumatic surgery, and to manage with aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy postoperatively. The preferred route of adjunctive therapy depends upon the severity of the uveitis. I agree with the audience that oral and topical/periocular therapy is optimal treatment for most patients. Of note is that I suggest using the most potent topical corticosteroid and starting corticosteroid therapy prior to surgery.1 In the past, we attempted to suppress inflammation in patients with uveitis, but now the goal is to eliminate inflammation in order to optimize surgical results.

1 Donnenfeld ED et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(4):609-617.

Nisha Acharya The key to performing phacoemulsification in patients with uveitis is to operate only if the uveitis is controlled on a stable medical regimen for a minimum of 3 months. Even with this uveitis quiescence, perioperative corticosteroids are still very important. Traditionally, oral corticosteroids were used, usually starting 3 days prior to surgery and tapering over approximately a month postoperatively. Frequent topical corticosteroids were only used postoperatively, and periocular corticosteroid injections were also performed for additional control. In patients who can tolerate oral corticosteroids, I still recommend a short course starting at 1 mg/kg of oral prednisone in most patients, but if there are contraindications to systemic steroids, an alternative regimen is a regional corticosteroid injection plus topical corticosteroids. With the advent of more potent topical corticosteroids like difluprednate, patients with less severe uveitis may have their inflammation sufficiently controlled in the postoperative period with this medication. In summary, there is no single correct answer here. The decision on what corticosteroids to administer should be individualized for patients, with patient preference and tolerability playing a big role in the decision-making process.

Q1.2 For a patient with 360 degrees of posterior synechiae, what is your primary preferred strategy for managing the small pupil?

|

Lyse synechiae + intracameral epinephrine/phenylephrine

|

19.9%

|

|

Pupil stretching

|

8.0%

|

|

Sphincterotomies + pupil stretching

|

4.9%

|

|

Iris retractors

|

31.8%

|

|

Pupil expansion ring (e.g., Malyugin)

|

35.5%

|

Eric Donnenfeld Small pupils are the enemy of good cataract surgery. Large pupils make good cataract surgeons great, while small pupils make great cataract surgeons nervous. In patients with posterior synechiae, there are 2 concerns: breaking the synechiae and enlarging the pupil. In patients with good potential dilation, I agree with answer #1, lysing the synechiae with viscodissection and then dilating the pupil with intracameral dilating agents. This is generally sufficient and is the least traumatic solution.

In general, I try to avoid pupil stretching or sphincterotomies, as they may permanently affect pupillary function. I will employ iris retractors if the pupil has been damaged and will not support a ring, but this is rarely the case. After the synechiae have been broken, I agree with the audience and prefer a pupil expansion device such as the Malyugin ring or the iRing.

Nisha Acharya It is extremely important to obtain adequate pupillary dilation that lasts the duration of the cataract surgery. In patients with uveitis, the iris may be friable, and there are often adhesions between the iris and the lens extending back from the pupillary margin. The posterior synechiae must be broken prior to any attempts to dilate the pupil. Once these adhesions are broken, iris retractors or a Malyugin ring are both helpful tools in expanding the pupil. Iris retractors can allow you to control the degree and location of dilation, depending on the placement of the retractors.

Case 2: Phaco With Fuchs Dystrophy

Q2.1 What is your target refraction for a patient with guttata who is undergoing phaco (and who historically likes and is accustomed to emmetropia)?

|

Plano (no change with guttata)

|

32.4%

|

|

Plano if mild guttata, but –0.75 to –1.00 if moderate/severe guttata

|

41.1%

|

|

–0.75 to –1.00 in all patients with guttata

|

20.7%

|

|

Slightly hyperopic

|

4.2%

|

|

I refer these patients

|

1.6%

|

Edward Holland The target refraction depends on 2 main factors: 1) the risk of corneal decompensation with phaco, and 2) if the risk of corneal decompensation is high, who the corneal surgeon will be and what the typical hyperopic shift is with that surgeon’s preferred endothelial keratoplasty procedure.

If the patient has mild to moderate guttata and is at very low risk for endothelial failure, there is no reason to select a myopic lens to offset the potential hyperopic shift that occurs with endothelial keratoplasty. If there is a high risk for decompensation (severe guttata), a myopic offset is warranted. However, the amount of myopic offset depends on the surgeon and their specific technique. Standard DSEK has the most hyperopic shift, ultrathin DSEK less, and DMEK a minimal effect. Each corneal surgeon knows their hyperopic shift, and the referring cataract surgeon should discuss this with the corneal specialist.

Dick Lindstrom All of the endothelial transplant procedures induce mild hyperopia, usually between 0.25 and 0.75 diopters. DMEK induces less hyperopia than DSEK, and a thinner DSEK less than a thicker DSEK. A busy corneal surgeon will know what the hyperopic shift is with their specific surgical technique, so if one works regularly with a particular corneal surgeon, the preferred refractive target can be discussed. I agree with the audience that with very mild guttata, where an endothelial transplant is unlikely, the refractive target can be the same as in a patient with a normal cornea. I also agree with the respondents that mild myopia is the best target when an endothelial transplant is more likely to be needed. I favor DMEK over DSEK, and I target –0.50 diopters in a patient with moderate to severe guttata if the patient is likely to need DMEK. For DSEK, I target –0.75 diopters. It is possible to safely perform a PRK enhancement in a patient in whom a DMEK or DSEK has been performed, but patients prefer mild myopia over induced hyperopia, and avoiding a second procedure is desirable.

Q2.2 What would you do for a symptomatic cataract patient with guttata (and 20/40 bedewing)?

|

First phaco only, then reassess visual acuity and function postoperatively

|

57.7%

|

|

Obtain cornea consultation prior to #1

|

30.2%

|

|

Recommend lamellar corneal transplant prior to phaco

|

0.8%

|

|

Recommend combined lamellar transplant + phaco

|

5.9%

|

|

#4 only if brunescent nuclear cataract

|

5.6%

|

Edward Holland This patient already has the clinical findings of stromal edema. I am surprised that so many of the respondents chose to perform phaco only and to reassess the vision postoperatively. With preexisting stromal edema, the cornea will only develop more edema postoperatively. In the vast majority of cases presenting with cataract and stromal edema, a combined phaco/endothelial keratoplasty should be performed. Response #2, obtaining a cornea consultation if the cataract surgeon is not sure what to do, is also appropriate.

There is one scenario in which the surgeon may want to perform phaco alone in a patient who has stromal edema. This is when there is a dense cataract and mild edema, with significant macular disease that would have a worse effect on vision than the corneal edema would. Removing the dense cataract and not addressing the residual mild stromal edema with coexisting macular pathology would result in improved visual acuity but not burden the patient with the postoperative management of an endothelial keratoplasty.

Dick Lindstrom The audience responses are again appropriate and reasonable. The classical symptom to ask for in the Fuchs dystrophy patient is so-called morning edema. In clinically significant Fuchs dystrophy, when the lids are closed overnight, the cornea swells, inducing epithelial microcystic edema, which causes blurry vision and halos around lights upon awakening. It is important to ask how long the blurring and halos last, which can be a few minutes to all day. If the morning edema lasts only a few minutes, patients may still do well with cataract surgery alone. If the morning edema lasts several hours, endothelial keratoplasty will nearly always be required. While endothelial cell counts are less useful in Fuchs dystrophy, the corneal thickness or pachymetry is helpful. The normal Caucasian cornea is 540 μm ± 30 μm thick. Thus, a pachymetry over 630 μm is present in less than 1% of normal patients. Corneal thickness between 640 and 700 μm suggests a cornea that is ready to decompensate and develop blurring from epithelial microcystic edema. When a pachymetry over 640 μm is associated with symptoms of morning edema, I am prompted to consider a combined cataract surgery with endothelial transplant approach.

In my opinion, it is always appropriate to offer the Fuchs dystrophy patient an attempt at cataract surgery first, and I continue to be surprised how often adequate visual rehabilitation is achieved, at least for a number of years in many patients with very significant and even confluent guttata. An endothelial transplant can always be performed when needed, and some very experienced corneal surgeons prefer a staged approach in all patients. However, if I am highly confident that an endothelial transplant will be needed, I personally do offer the patient a combined procedure; for me, that usually is phacoemulsification combined with DMEK, thus avoiding 2 separate trips to the operating room.

|

|

CASE 2. The choice of target refraction is an important preoperative consideration for Fuchs patients with cornea guttata.

|

Case 3: Posterior Polar Cataract

Q3.1 For a posterior polar cataract, I would …

|

Hydrodissect and hydrodelineate

|

16.0%

|

|

Hydrodelineate with balanced salt solution

|

59.4%

|

|

Hydrodelineate with ophthalmic viscoelastic device

|

14.8%

|

|

Skip all hydrosteps

|

7.5%

|

|

Refer these cases

|

2.3%

|

Terry Kim General principles for approaching a posterior polar cataract include avoiding excessive intralenticular pressure from any source, as well as limiting downward pressure on the capsule. The practice of performing hydrodelineation with balanced salt solution (BSS) only—and specifically avoiding hydrodissection—is recommended to minimize the risks of rupturing the posterior capsule. This corresponds with the majority vote of the audience.

Abhay Vasavada Creating an epinuclear cushion effect to protect the fragile posterior capsule is logical and reduces the stress to the capsule while the central nucleus is being removed. Of the respondents, 74% achieve this by hydrodelineation with either BSS or ophthalmic viscoelastic device (OVD). We find the inside-out hydrodelineation technique useful: After a central trench is created in the anterior epinuclear material, fluid is slowly injected into the core of the nucleus until a golden ring is seen. When low phacoemulsification settings are used, this technique avoids inadvertent passage of fluid into the subcapsular plane.

Very few of the respondents additionally perform hydrodissection. In cortical-cleaving hydrodissection, it is very important to inject only a small amount of fluid gently in such a way that the fluid wave does not reach the central posterior capsule. To be effective, it becomes necessary to repeat the injection in multiple quadrants.

Only a few audience members avoid all hydroprocedures. This can make epinucleus and cortex removal more difficult and unpredictable. In my experience, femtodelineation using femto-assisted cataract surgery has been very beneficial in avoiding hydroprocedures. The removal of epinucleus and cortex is not difficult because the laser-cut, smooth wall of epinucleus is easily occludable with the phaco tip and aspiration port of I/A tip.

Q3.2 What is your personal posterior capsular rupture rate with posterior polar cataracts?

|

1% or less

|

28.4%

|

|

2%-5%

|

14.7%

|

|

5%-15%

|

8.9%

|

|

>15%

|

4.8%

|

|

Insufficient experience to know

|

43.2%

|

Terry Kim Studies in the peer-reviewed literature report a 26%-36% incidence of posterior capsular rupture with posterior polar cataracts.1,2 Most of the audience claimed insufficient experience to know their rate, while others claimed a much lower incidence. With proper surgical techniques, we can all lower our risk of this well-known complication of posterior polar cataract removal.

1 Osher RH et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1990;16(2):157-162.

2 Vasavada AR, Singh R. Phacoemulsification in posterior polar developmental cataracts. In: Lu LW, Fine IH, Phacoemulsification in Difficult and Challenging Cases. New York, NY: Thieme: 1999: 121-128.

Abhay Vasavada It is too good to be true that 28% of the respondents have a posterior capsular rupture rate of 1% or less. It is very important to differentiate posterior subcapsular “plaque” cataract from a posterior polar cataract (PPC). PPC is an uncommon condition compared with subcapsular cataract. A typical PPC has a bull’s-eye appearance with concentric rings surrounding a central plaque area. Creating an epinucleus cushion; adhering strictly to the principles of closed-chamber technique, including preventing forward bulge of the capsule–iris diaphragm; and using “slow motion” technique for lens removal certainly will help in reducing the rupture rate.

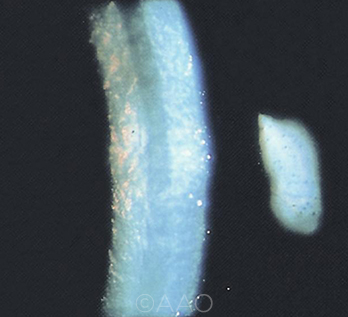

|

|

CASE 3. The literature has shown a posterior capsular rupture rate of 26%-36% in patients with posterior polar cataract.

|

Case 4: IFIS & Small Pupil

Q4.1 Which of the following brand-name prostate medications is least likely to cause severe intraoperative floppy iris syndrome?

|

Flomax

|

13.0%

|

|

Uroxatral

|

39.0%

|

|

Jalyn

|

28.5%

|

|

Rapaflo

|

19.5%

|

David Chang Because patients might list either, it is important for cataract surgeons to recognize both the brand and generic names for systemic alpha antagonists. Flomax (tamsulosin) was the first approved systemic alpha-blocker that specifically blocks the alpha 1A receptor subtype, which predominates in the prostate. Rapaflo (silodosin) was the second alpha 1A subtype–specific alpha antagonist to be approved. Being in the same pharmacologic class as tamsulosin, it demonstrates a similar propensity to cause intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS). Jalyn is a combination of tamsulosin and dutasteride, a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor that shrinks the size of the prostate. Combination therapy was shown to decrease the progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) compared to monotherapy with either agent.1 Uroxatral is alfuzosin, which is a nonspecific alpha antagonist. We conducted a prospective, masked comparison of cataract surgery in patients taking tamsulosin, alfuzosin, or no alpha-blockers.2 Alfuzosin was statistically less likely to cause severe IFIS and is the correct answer.

1 Roehrborn CG et al. Eur Urol. 2010;57:123-131.

2 Chang DF et al. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):829-834.

Q4.2 What is your preferred initial strategy for a patient in whom you anticipate severe IFIS?

|

Retentive OVD (e.g., Healon 5) to viscodilate

|

9.7%

|

|

Intracameral epinephrine or phenylephrine

|

32.6%

|

|

Iris retractors

|

20.8%

|

|

Pupil expansion ring (e.g., Malyugin)

|

35.5%

|

|

Other

|

1.5% |

Tom Oetting When I face a situation where the likelihood of IFIS is high (e.g., selective alpha-blocker like tamsulosin and the pupil starts off small), I prefer to use the Malyugin ring. I will shift to iris hooks if the angle is narrow, if the patient has significant central posterior synechiae, or if the patient has a very hard lens and may need conversion to extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE). I typically use the smaller 6.25-mm Malyugin ring, as it is easier to place and remove than the larger 7.0-mm ring. However, I suggest using the 7.0-mm Malyugin ring if the pupil diameter is on the larger side, or if I plan to use a large-optic intraocular lens (IOL) such as the 6.5-mm Alcon MA 50.

The most important tip: Do not completely retract the ring into the cylinder of the inserter when removing the ring. If you try to completely retract the ring into the cylinder, funny things can happen if the lateral eyelets catch and flip the ring under the inserter. Just bring the ring into the inserter enough to bring the lateral eyelets near the opening of the inserter. Thank you to Dr. Boris Malyugin for this great device, which is most useful.

Boris Malyugin One can expect IFIS in male patients taking selective alpha 1A–blockers. Lately, some other medications (for instance, antidepressants) have been linked to that syndrome. Some studies showed that the incidence of IFIS in females is higher than previously thought. Gender distribution among IFIS cases was 57.1% males vs. 42.9% females.1

However, a certain drug regimen is not always a perfect predictor of IFIS, as we know that 14% of patients may develop idiopathic IFIS, which is not induced by any of the known medications linked to that condition.2

So, the question is whether or not the IFIS can be anticipated. And the answer to that question is: Yes, it is possible to anticipate IFIS by assessing the pupil size. When the pupil is opened insufficiently (within the range of 5.0-7.5 mm), the chance of having severe (Grade 3) IFIS is 3.8 times higher than in patients with pupils of 8.0-10.0 mm in diameter.2

My personal strategy in IFIS is to inject phenylephrine 1% into the anterior chamber first, as suggested by Richard Packard. That maneuver not only expands the pupil but also helps to increase the tone of the iris dilator muscle and to improve biomechanical stability of the iris by increasing the rigidity of its tissue. This strategy came in at only second place among respondents, which I believe reflects the limited access to intracameral mydriatics.

Recently, Omidria, which is the combination of phenylephrine 1% and ketorolac 0.3% to be added into the BSS bottle, was introduced in the United States. And I believe that its use as a preventive strategy in patients for whom one can anticipate IFIS is worthwhile. In Europe, surgeons have access to Mydrane (Thea), which is a mixture of 0.31% phenylephrine + 0.02% tropicamide + 1% lidocaine HCl. This combination is indicated for intracameral injection at the very beginning of the surgical procedure to support mydriasis and decrease sensation in the patient.

The use of pupil expansion rings is the strategy preferred by the majority (35.5%) of the respondents. This is an extremely effective procedure to be used primarily or as a second step when for some reason intracameral mydriatics did not work well or are not available.

My personal preference is the second generation of the Malyugin Ring 2.0, which is made of 5/0 polypropylene and is more pliable and gentler on the iris. The 7.0-mm ring works best in IFIS cases, as the pupil might not be very small at the very beginning of the surgical procedure.

Iris retractors (the third most common option among audience respondents) can also be effectively utilized in IFIS cases. I like the idea of placing the retractors in the “diamond” configuration. Placing one of the retractors close to the main incision helps the instruments to go in and out of the incision without the risk of iris prolapse.

Personally, I am not a big advocate of retentive OVDs as a primary measure to fight IFIS. These substances do not stay in the anterior chamber long enough, and repeated reinjections during the course of lens evacuation are usually necessary. However, this can be used as an augmenting maneuver, as the use of the heavy OVDs may help the surgeon to place and to remove the pupil expansion ring more easily.

1 Wahl M et al. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Published online Oct. 19, 2016.

2 Chang D et al. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):829-834.

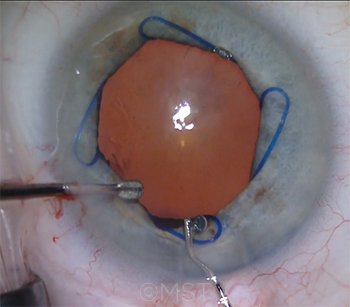

|

|

CASE 4. The majority of the audience said that use of a Malyugin ring is their preferred strategy for patients in whom severe IFIS is anticipated.

|

Case 5: Mature White Lens

Q5.1 What is your capsulotomy technique for a white lens in a young patient?

|

Healon 5 + capsule forceps

|

18.2%

|

|

Other OVD + capsule forceps

|

23.9%

|

|

First use a needle to aspirate some cortex

|

45.5%

|

|

Femtosecond laser capsulotomy

|

9.2%

|

|

Would refer this patient

|

3.2%

|

Soon Phaik Chee The challenge in a mature white lens in a young patient—where the lens is likely to be swollen—is making the capsulotomy in the presence of high intralenticular pressure. Hence, I would give intravenous mannitol 30 minutes preoperatively and minimize the speculum pressure. If capsular fibrosis is present and likely to affect the capsulorrhexis, I prefer femtosecond laser–assisted capsulotomy, adjusting the settings to increase the laser energy and taking care to achieve level docking to obtain a complete capsulotomy.

In the absence of significant capsular fibrosis, either femto-capsulotomy or conventional phacoemulsification is acceptable. I use trypan blue to stain the anterior capsule to improve visibility. Then I pressurize the anterior chamber with retentive viscoelastic and, using the cannula, make gentle sweeping movements over the center of the swollen lens to flatten the anterior capsule. With a 27-gauge needle, bevel up, I simultaneously puncture the flattened anterior capsule and aspirate the liquefied lens cortex. The viscoelastic cannula is next used to sweep over the intact capsule from the periphery of the lens centripetally, milking the swollen lens material toward the center, thus flattening the midperipheral lens. I inject viscoelastic at the same time to pressurize the anterior chamber. This allows the capsulorrhexis of the desired size to be safely created with minimal risk of run-out as the capsulorrhexis is torn over the flattened anterior capsule. This technique of initially aspirating the cortex is commonly practiced, with more than 45% of the audience using this currently. The additional steps I described above avoid the need to enlarge the capsulorrhexis at the end of the case, as the initial capsulorrhexis is often smaller than desired.

Q5.2 What is your strategy for an “Argentinean flag” tear in a white cataract with 3+ nuclear sclerosis?

|

Phaco in bag after enlarging the capsulotomy

|

30.8%

|

|

Prolapse the nucleus and phaco in the anterior chamber

|

47.9%

|

|

Convert to a large-incision manual ECCE

|

15.3%

|

|

Convert to a sutureless small-incision manual ECCE

|

4.9%

|

|

Abort surgery and refer the patient

|

1.2%

|

Soon Phaik Chee I would generally prefer to continue with phacoemulsification, using a direct chop technique with standard settings. I would initially aspirate more of the swollen cortex from under the intact anterior capsule, inject retentive viscoelastic over the midperipheral capsule, and pressurize the anterior chamber. Using microscissors, I would initiate a capsulorrhexis of about 6 mm in diameter with an adequately long snip of the capsule (larger than usual to avoid stressing the anterior capsule rip and risking posterior extension during fragment lateral separation movements required in a moderately dense cataract) and make the tear using microcapsule forceps. I would avoid sculpting and instead initiate phaco by burying the phaco tip into the core of the nucleus to obtain adequate purchase before starting to chop. However, if I am faced with a leathery posterior plate, I would inject dispersive viscoelastic into the bag to bring the nucleus into the anterior chamber and complete the phaco in the anterior chamber with supplemented endothelial protection. It is important to emphasize that before removing instruments from the anterior chamber, one should always inject viscoelastic into the anterior chamber to prevent the chamber from flattening and risking posterior extension of the anterior capsule rip. The haptics of the IOL should be placed perpendicular to the direction of the anterior capsule tears.

Almost a quarter of the audience responded that they would not proceed with phaco. Almost half would have brought the nucleus into the anterior chamber to phaco, while the remaining third would have tackled it in the bag after enlarging the capsulotomy. I believe that this choice is guided by the experience of the surgeon. Prolapsing the nucleus in the anterior chamber to do the phaco itself may increase the risk of posterior capsule extension, except in experienced hands; it also increases the risk of endothelial damage. This technique can be challenging in the presence of a thick nucleus and a shallow anterior chamber.

Bob Osher In order to answer this question accurately, it is necessary to differentiate between the 3 types of white cataracts. The hard (mature) white cataract is simply a challenge requiring a capsular dye for visualization and patience. The morgagnian cataract has a liquefied cortex that will escape into the anterior chamber, causing the capsule to collapse around the very hard nucleus. The capsulotomy is best managed by reinflating the capsular bag with OVD, which serves to separate the anterior and posterior capsules.

The third type, the intumescent white cataract in the younger patient, is associated with the Argentinean flag sign. Some liquefaction has occurred anterior and posterior to a nuclear block. There is increased intralenticular pressure in both the anterior and posterior cortical compartments. An excellent article written by Dr. Carlos Figueiredo from Brazil recommends using a retentive OVD, which serves to pressurize the anterior chamber; staining the anterior capsule with trypan blue; and performing a small rhexis to reduce any tendency for the anterior capsule to run.1 A key principle is posterior voiding, which decompresses the pressure in the posterior cortical compartment by balloting or dribbling the nucleus toward the retina. After this maneuver, there is no longer a tendency for an Argentinean flag, and the rhexis can be enlarged to facilitate the emulsification and removal of cortex. Therefore, it is not enough just to decompress the anterior cortical compartment, as many physicians prefer to do. Moreover, it should be kept in mind that the anterior capsule is less elastic whenever trypan blue is used for staining the capsule.

1 Figueiredo CG et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(9):1531-1536.

|

|

CASE 5. The approach to mature white cataract depends on its type, according to Dr. Osher.

|

Case 6: Rock-Hard Nucleus

Q6.1 What is your usual technique for the rock-hard cataract?

|

Divide and conquer

|

43.0%

|

|

Phaco chop

|

35.7%

|

|

Manual ECCE

|

5.9%

|

|

I do both phaco or ECCE—it just depends on the patient

|

14.9%

|

|

I would refer these patients

|

0.5%

|

Amar Agarwal When a rock-hard cataract, meaning something like a black cataract, is present, I think the best way to operate is to do an extracapsular cataract extraction, or ECCE. One can also do a SICS, or manual small-incision cataract surgery, provided one is well versed in it. The audience poll shows divide and conquer in phaco as the top answer. The problem in divide and conquer is that too much energy is being used, and every time you groove into the cataract you create pressure on the posterior capsule by manual pressure itself. If one wants to do a phaco, the way to do it is to use the phaco chop technique and also use the air pump or gas-forced infusion. This was started by Dr. Sunita Agarwal in 1999 for phakonit, or bimanual phaco. Since then, we have used it routinely in all our coaxial phaco cases. This technique or its modifications are now available in nearly all phaco machines. It makes the anterior chamber deep so that we can work faster and more easily, with less damage to the endothelium or posterior capsule. A final point to remember: If doing a phaco in rock-hard cataract, do ask your assistant to irrigate the corneal wound with BSS so that the patient does not get a corneal burn.

Kevin Miller The majority of the audience would approach the patient with a rock-hard nucleus as a candidate for some form of phacoemulsification. Some would consider an ECCE, depending on the details. Only 5.9% would go straight to an ECCE. I belong to the large group of ophthalmologists who approach the majority of patients as candidates for phacoemulsification. If the zonules are too loose to make phacoemulsification possible, I would go with an intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE). I almost never plan to perform an ECCE. Instead, I convert to ECCE if phacoemulsification is taking too long or not progressing properly.

There are slightly more ophthalmologists who would perform a divide-and-conquer procedure than a chop procedure. I think the specific approach depends on the experience and comfort of the surgeon. While chop procedures generally allow nucleus disassembly with less applied ultrasound energy, sometimes it is impossible to impale the rock-hard nucleus to obtain purchase before chopping. In these cases, one must resort to a divide and conquer. It is important in all such cases to use some form of pulse modulation to limit the applied energy and liberally apply a dispersive OVD to protect the corneal endothelium and posterior capsule.

Q6.2 Describe your experience with manual large-incision ECCE

|

Very experienced

|

33.4%

|

|

Some experience (and I am comfortable with ECCE)

|

23.5%

|

|

Some experience (but I am not that comfortable with ECCE)

|

21.7%

|

|

Very limited (or no) experience

|

14.7%

|

|

I am also comfortable with sutureless, manual small-incision ECCE

|

6.8%

|

Amar Agarwal Most of the audience knows how to perform an ECCE. That is a good sign, as this is an important technique that the surgeon should master. In black, hard cataracts, an ECCE may be better than even a SICS. In ECCE, all one has to do is a linear capsulotomy. Just a straight line over the anterior capsule is easier than making a circle, as is done in a capsulorrhexis. Struggling with a 6-mm SICS incision may not be the answer in black cataracts, especially for the novice surgeon. A good ECCE gives excellent results with less chance of a dropped nucleus and posterior capsular rupture.

Kevin Miller It appears that the majority of ophthalmologists feel comfortable performing ECCE. This is good. Hopefully, a similar number are comfortable performing ICCE. For those who are not, this would be a good skill to acquire in a Skills Transfer course offered by the Academy or ASCRS.

Case 7: Anterior Vitrectomy

Q7.1 Describe your experience with pars plana anterior vitrectomy.

|

Have tried it, and it is my preference

|

27.7%

|

|

Have tried it—it’s a bad idea or I am not comfortable

|

8.7%

|

|

Have never tried it, but I would consider trying

|

42.8%

|

|

Have never tried it, and I wouldn’t ever do it

|

20.9%

|

Rudy Nuijts It is clear from the responses that anterior segment surgeons in general (>70%) do not feel comfortable with switching to the posterior side of the eye. I, personally, believe that a posterior approach is best performed using the vitreoretinal instrument armamentarium (27 gauge, etc.) and should be reserved for experienced surgeons. In general, when appropriate techniques are used (separated cutting and infusion, or even dry vitrectomy, use of triamcinolone), an anterior approach will be efficient for removing the vitreous from the anterior segment.

Susan MacDonald I have found that a pars plana anterior vitrectomy is superior to an anterior vitrectomy through side ports. I have found it extremely successful in managing a posterior capsule rupture or zonular dehiscence with vitreous that has prolapsed into the anterior chamber. It allows for gentler and more efficient removal of the vitreous, pulling it back into the posterior chamber and out of the anterior chamber. This limits the tension on the vitreous, and it can limit the tear of the posterior capsule. For those considering changing their technique, I would recommend taking an Academy course with a wet lab.

Q7.2 Does femtosecond laser–assisted cataract surgery (FLACS) reduce the posterior capsule rupture (PCR) rate, compared with manual phaco?

|

Yes, for both routine and complex cases

|

8.8%

|

|

Yes, but for complex cases only

|

10.5%

|

|

No, the PCR rate is equivalent

|

21.0%

|

|

No, the FLACS PCR rate is higher

|

20.5%

|

|

Not sure

|

39.2% |

Rudy Nuijts In the 2014 European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS) FLACS vs. phaco case control study, PCR rate was similar at 0.3% in both groups. Also, in various Australian articles overall, the intraoperative complication profile of FLACS, including posterior capsule tears and dropped nuclei, was comparable to or even better than conventional phaco. The introduction of any new technique or device clearly involves a learning curve. With respect to FLACS, this was related to buildup of cavitation bubble pressure in the bag which, in initial series, led to an increased rate of blowout posterior capsule ruptures after forceful hydrodissection. Currently, FLACS does not lead to higher PCR rates, a phenomenon that does not appear to be known to the audience.

Susan MacDonald FLACS does not reduce the posterior capsule rupture rate compared with manual phaco. As Dr. Nuijts points out, there were earlier case reports of PCR due to cavitation bubble pressure blowing out the posterior capsule. This has been addressed by software adjustments. Intraoperative capsular blockage syndrome was first reported in 2011,1 identifying capsule rupture with aggressive hydrodissection. The increased pressure can cause PCR. This can be avoided by gentle hydrodissection and a gentle rocking of the nucleus to release any trapped fluid or gas bubbles.

1 Roberts TV et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(11):2068-2070.

Case 8: Phaco & Diabetic Retinopathy

Q8.1 Would you implant a diffractive multifocal IOL in a young insulin-dependent diabetic with good blood sugar control (who wants a multifocal IOL)?

|

No, would not implant a multifocal IOL in this patient

|

33.1%

|

|

Yes, but only if there is no diabetic retinopathy at all

|

28.9%

|

|

Yes, if there is no more than mild background diabetic retinopathy, and no macular edema

|

12.5%

|

|

I would discourage it, but, yes, would if the patient insists despite the risk

|

23.0%

|

|

I would refer this patient

|

2.4%

|

Julia Haller There’s a good reason that the audience is cautious here: This is a tough decision. That’s why we see a split between an absolute “no,” a “discourage, but implant if the patient insists despite the risk,” and a “yes, but only if there is no diabetic retinopathy at all,” because everyone is rightly worried about long-term outcomes in this young insulin-dependent diabetic. We know that virtually 100% of patients with type 1 diabetes will eventually get retinopathy, although we are better and better at treating it and preventing visual loss, if we can catch it early. No conscientious surgeon wants to implant a multifocal IOL if there is a good chance that the patient will have problems with it down the road. And we know that young diabetics can be very difficult to follow, although we are encouraged that this particular patient has good blood sugar control now, which is a positive sign that long-term systemic health outcomes—which translate into long-term eye health outcomes—are more likely to be good. As a retina surgeon, I probably have a skewed view of this population, with a darker outlook. That said, I would side with the slim majority here who voted “no” but acknowledge the positivity and caution of almost all of the respondents. Good job, audience!

Paisan Ruamviboonsuk Interestingly, although choice #1, “No, would not implant a multifocal IOL in this patient” (the only choice with a “no” answer) got the highest percentage of votes, a total of 64.4% of the responders still voted yes, with different reservations. The responders who voted yes might have been thinking about the stability of diabetes in this patient and the availability of useful treatments for vision restoration in diabetic retinopathy that exist today. However, another factor that we should think about is the fact that this patient is insulin dependent, and retinopathy develops more aggressively in these patients than in those who are not insulin dependent. Another fact is that retinopathy is usually worsened after cataract surgery.

I personally would choose answer #1 and might cautiously choose #4, although the decision seems to be made on the patient side.

Q8.2 Your preoperative assessment for a 3+ nuclear sclerotic (NS) cataract in a patient with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR):

|

I’m comfortable ruling out diabetic macular edema (DME) without OCT

|

8.2%

|

|

I’m comfortable ruling out DME with OCT

|

65.2%

|

|

I refer all NPDR patients to a retina specialist for preop assessment

|

10.9%

|

|

I refer to retina specialist only if I suspect DME

|

12.7%

|

|

I would schedule phaco regardless, and plan to refer the patient to a retina specialist postoperatively if necessary

|

3.0%

|

Julia Haller This question and the responses show the sea change in ophthalmic practice since the introduction of optical coherence tomography. Many, if not most, comprehensive ophthalmologists and cataract surgeons now routinely screen patients with OCT and feel comfortable with this diagnostic modality. I interpret answers 2 and 4 as meaning that the cataract surgeon has performed an OCT and feels comfortable judging whether there is or is not DME. This adds up to 77.9% of the audience—a remarkable and heartening finding, when we think ahead to the huge burden of diabetes escalating globally and the growing demands on our profession for its management. When you add in the 10.9% of physicians in the audience who cautiously refer all diabetic patients to a retina specialist preoperatively, we have a huge majority of respondents demonstrating a very high level of retina sophistication. These surgeons are alert to the threats and challenges of the diabetic eye. They clearly have gotten the crucial message that diabetes is the No. 1 cause of preventable blindness in the developed world and that diabetic macular edema is the No. 1 cause of blindness in working-age Americans. This is good news for their patients and happy-making to those of us in academic retina!

Paisan Ruamviboonsuk One of the reasons why we very much rely on OCT today—despite the fact that it can show only the anatomic appearance of the macula, not function—is because we can share and explain the evidence on OCT with patients and their relatives rather easily. With 3+ NS cataract, although some experienced ophthalmologists may be comfortable ruling out DME without OCT, having evidence to share with patients would be preferable. I think laser from the OCT machine can still penetrate the 3+ NS and detect DME, although the images may not be very clear.

It is better to detect any macular lesions preoperatively rather than postoperatively (choice #5). This is not only so that we can inform patients about their visual prognoses more precisely but also so that we can plan better for appropriate management, such as preoperative or intraoperative intravitreal injection.

Case 9: Phaco With Glaucoma

Q9.1 Would you combine a glaucoma procedure for a cataract patient with early visual field loss + IOP 20 on 2 medications?

|

Yes, trabecular bypass stent (e.g., iStent)

|

23.3%

|

|

Yes, other microinvasive glaucoma surgery device/procedure

|

6.7%

|

|

Yes, combine trabeculectomy

|

11.3%

|

|

No, I would do phaco only

|

53.0%

|

|

I would refer this patient

|

5.8%

|

Reay Brown I implant an iStent in all mild-to-moderate glaucoma patients who have cataract surgery. Since the iStent is approved only for use at the time of cataract surgery, this is the only opportunity to use this device to either lower the IOP, reduce the number of eyedrops, or both. The iStent can “bend the curve” of glaucoma damage and reduce the risk of future problems. The specified patient is in the mild-to-moderate category, and my expectation with an iStent/phaco would be for a pressure reduction of 4-5 mm Hg on average, which may allow for the discontinuation of 1 or more medications, depending on the visual field. It is possible that this same patient would also benefit from the CyPass, which was approved by the FDA last summer. I would not consider a trabeculectomy in this patient because the benefit is not worth the risk of an external drainage procedure in this early stage of glaucoma. Furthermore, a trabeculectomy often has a negative impact on the visual recovery and the ability to use toric IOLs.

Rick Lewis Combining a glaucoma procedure with the phaco is generally my recommendation in a setting of visual field loss and an IOP of 20. The specifics of which procedure among the various combinations to use depend on the severity of the glaucoma and the risk factors for the individual patient. The options available are expanding, with a wider choice of small-incision ab interno microinvasive glaucoma surgery procedures, as well as the more traditional tubes and trabs. The current options are safer and allow for more aggressive management of the patients with well-defined glaucoma, reducing the risk of hypotony and complicated postoperative care.

Q9.2 What topical steroid would you initiate for a phaco patient with open-angle glaucoma on 2 IOP medications?

|

Usual steroid, no change

|

72.4%

|

|

Usual steroid, but decrease duration or dosing

|

17.1%

|

|

Switch to “weaker” topical steroid

|

8.3%

|

|

No topical steroid initially

|

1.4%

|

|

Inject intraocular steroid only

|

0.7%

|

Reay Brown I would use my usual steroid protocol for this patient. But where I usually see cataract patients at 1 day and 1 month, I would see patients like this at 2 weeks instead of 1 month. Eyes with glaucoma often have more inflammation and so benefit from steroids. But the case can be made for reducing the frequency or duration of steroids—or using a weaker steroid—because of a concern about raising the pressure. Although I watch carefully for steroid-related glaucoma, I don’t have a sense that pressure elevation has been a big problem for my patients—or at least it has been easy to treat it by stopping the steroids. It is rare to have a steroid response before a week of treatment, and it is most common after 3 or 4 weeks, so this is usually long enough that most of the steroid benefit has already occurred. We need to watch for pressure elevation more closely when using more potent steroids. We also need to be attentive to the risk of steroid glaucoma in patients receiving an iStent.

Rick Lewis Steroid use in glaucoma patients is always a concern. One important rule of thumb is that steroids do not cause an IOP elevation on day 1. Most often, such an early increase can be attributed to retained viscoelastic. In most studies, prolonged steroid use requires 2-4 weeks before an IOP response is noted. For a steroid-responsive patient, there is no steroid currently available that eliminates this risk. Anti-inflammatory treatment is clearly necessary in managing postoperative cataracts. For a patient at high risk of a steroid-induced IOP rise, NSAIDs are an option. However, for those patients who require steroids in this setting, I recommend using only a topical steroid (and avoiding injecting in the vitreous or subconjunctival space) that could be discontinued if the IOP is elevated.

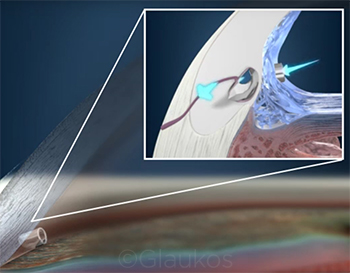

|

|

CASE 9. Dr. Brown says that he implants the iStent in many of his patients with mild-to-moderate glaucoma in an effort to lower IOP and/or reduce the number of medications needed to control the disease.

|

Case 10: Pseudoexfoliation/Weak Zonules

Q10.1 Upon initiating surgery and discovering that the zonules are extremely weak, what would you do next?

|

Carefully continue phaco without any devices

|

38.8%

|

|

Insert a capsular tension ring (CTR) and then resume phaco

|

18.7%

|

|

Insert capsule/iris retractors and then resume phaco

|

13.9%

|

|

Insert capsule retractors + CTR and then resume phaco

|

23.7%

|

|

Convert to a manual extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE)

|

4.8%

|

Rosa Braga-Mele Diffuse or localized zonular weakness can usually be identified during capsulorrhexis early on, which makes management more immediate and, typically, easier. It is important to do a gentle hydrodissection. If the weakness is localized, then I typically prefer to continue gentle phaco without any devices, as long as I can stay away from the area of weakness and create the least amount of stress. If this is not feasible, then I will typically use capsule retractors in the area of weakness and continue phacoing. If the weakness is diffuse, I would prefer to insert a CTR to allow any zonular stress to be minimized, and will use some capsular hooks in areas that may be weaker than others. If necessary, one can sew in an Ahmed segment or a Cionni ring at the end of the case. If the weakness is significant and there is a large lateral movement of the nucleus, then converting to a manual ECCE may be the only option.

Tom Samuelson Unanticipated intraoperative discovery of loose zonules should be an uncommon occurrence. In most cases surgeons should have a strong suspicion based on the preoperative exam, recognizing clues such as exfoliation, unilateral shallowing of the anterior chamber often associated with a slightly larger pupil, iridodonesis, or frank phacodonesis. The first intraoperative clue suggestive of zonulopathy is pronounced dimpling of the anterior capsule noted when the cystotome first penetrates the capsule. Upon the initial discovery of loose zonules, like the majority of the respondents surveyed, I typically continue on with the procedure, taking great care to avoid unwarranted zonular stress. However, if additional risk factors are present, such as IFIS or a poorly dilating pupil, I have a very low threshold for placing a pupil-expanding device. If the zonulopathy is mild, I generally don’t use a CTR. If the zonular weakness is more than mild, I will use a standard CTR. If zonulopathy is severe, a sutured CTR is required. I generally don’t use capsular hooks unless the zonulopathy is profound and I am unable to complete the rhexis, lens emulsification, or IOL implantation without them. As a rule, if capsular hooks are needed, a standard CTR will not adequately support the IOL/capsular complex, and a sutured modified CTR or sutured segment is necessary.

Q10.2 With advanced diffuse zonulopathy in a pseudoexfoliation patient, what method of posterior chamber (PC) IOL fixation would you employ?

|

Intracapsular with no CTR

|

20.6%

|

|

Intracapsular with a CTR

|

42.4%

|

|

Intracapsular with a Cionni/Malyugin CTR, or Ahmed capsular tension segment

|

7.0%

|

|

Sulcus without any haptic suture fixation

|

27.3%

|

|

Sulcus with haptic suture fixation

|

2.6%

|

Rosa Braga-Mele I tend to agree with the audience on this question. I would likely put in a CTR and implant a single-piece IOL in the bag. However, this would be best if it were a nonprogressive zonulopathy. In a progressive zonulopathy, sewing in either a CTR or a suture-fixated IOL would likely be the best option and would likely delay any decentration and further surgery.

Tom Samuelson If I am confident of the capsular stability, I will implant a 1-piece acrylic IOL in the bag, generally with a CTR to better maintain centration. However, when in doubt, sulcus placement of a 3-piece IOL with optic capture is a good strategy. If I have any concern that the IOL will be unstable or not remain adequately centered, suture fixation to the iris is an easy and reassuring measure. The “flanged IOL fixation with double needle” technique described by Shin Yamane of Japan (in an award-winning video presentation at the 2016 ESCRS meeting in Copenhagen) is another novel IOL fixation method that is elegant and minimally invasive.

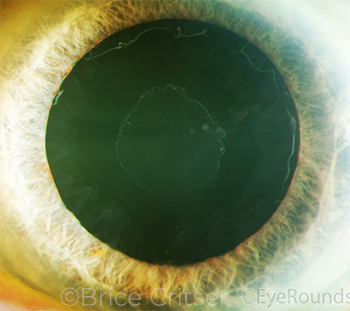

|

|

CASE 10. Loose zonules may be heralded by several preoperative clues, including exfoliation (shown here) and unilateral anterior shallowing that may be associated with a slightly larger pupil, iridodonesis, or frank phacodonesis.

|

Case 11: Delayed Bag-IOL Dislocation

Q11.1 How would you manage a delayed bag-IOL inferior subluxation in a pseudoexfoliation patient with a 3-piece IOL and no CTR?

|

I would suture-fixate the IOL/haptic

|

41.2%

|

|

IOL exchange with a PC IOL

|

6.7%

|

|

IOL exchange with an anterior chamber (AC) IOL

|

14.3%

|

|

Refer to anterior segment surgeon

|

21.6%

|

|

Refer to posterior segment surgeon

|

16.2%

|

Nick Mamalis Late-onset spontaneous IOL dislocation within the lens capsular bag is being seen more frequently with the advent of continuous curvilinear capsulorrhexis (CCC) followed by phacoemulsification and placement of an IOL within the capsular bag. Studies at the Intermountain Ocular Research Center of the Moran Eye Center have shown that the most common etiology for this condition is pseudoexfoliation with a diffuse zonulopathy, leading to delayed dislocation of an IOL within the capsular bag approximately 9• years (on average) following uneventful cataract surgery. Pseudoexfoliation has been the most common etiologic factor noted in these cases evaluated; half to approximately 66% of the cases with delayed dislocation of the IOL within capsular bag had pseudoexfoliation.

The most common method for managing this condition was suture fixation of the IOL/haptic, which 41.2% of the respondents chose. Other options, such as exchanging the IOL with either a posterior chamber or an anterior chamber IOL, were noted much less frequently. The second most common answer was to refer this patient to an anterior segment surgeon. There are now many methods for fixating a subluxated IOL–capsular bag complex to the sclera/ciliary sulcus, which can be done safely within a closed system, utilizing various techniques and different suture types.

Alan Crandall In this eye with pseudoexfoliation and late subluxation of the IOL-bag complex, we have a 3-piece IOL and no CTR. The first question that I ask the patient is, “Was the vision good with the implant?”

If they had good vision, I would opt to use small incisions to fixate the IOL. There are a number of techniques we can use.

- One is to elevate the lens so the optic is in the anterior chamber and the haptics are in the posterior chamber.

- If there is a Soemmering’s ring, I remove it and the capsule. I will then use 10-0 or 9-0 Prolene sutures to iris-fixate the lens.

- Using a Siepser technique, we can often use only 2 or 3 small incisions with a stab knife. I also use vitreous stain to watch for vitreous that might move forward, and I use an anterior vitrectomy unit to remove any vitreous in the anterior chamber.

If the vision was not good because of IOL power issues or a damaged IOL, then I would explant the lens. If the patient does not have glaucoma, then one could use an anterior chamber lens, but I would prefer an Artisan (iris-claw) lens (not FDA approved, but an ongoing study is in progress). Another option is scleral fixation, for which I usually use an Akreos lens (Bausch + Lomb).

If the capsule and haptics are strongly adherent, another technique has been described by Garry Condon. A peritomy is performed, and 2 incisions are made 2 mm posterior to the limbus; a 9-0 Prolene suture on a long, curved needle is passed under and then through the bag near the haptic and passed through peripheral cornea; viscoelastic is used to push the complex posterior to the scleral incisions; and an MST Snare or any hook retrieves the suture above the complex, thus encircling the haptic bag complex without docking or other complex maneuvers. This works well especially if there is a CTR in place.

Further reading:

Chan CC et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(1):121-128.

Davis D et al. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(4):664-670.

Jehan FS et al. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(10):1727-1731.

Kirk TQ, Condon GP. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(10)1711-1715.

Q11.2 What percentage of your pseudoexfoliation eyes get a CTR?

|

I don’t use CTRs

|

27.3%

|

|

<10%

|

53.7%

|

|

10%-50%

|

12.2%

|

|

>50%

|

6.0%

|

|

I refer these patients

|

0.7%

|

Nick Mamalis There has been speculation that placement of a CTR within the capsular bag at the time of cataract surgery will help to resist the contractile forces caused by fibrous metaplasia of the anterior lens epithelial cells, with subsequent shrinkage of the capsulorrhexis or phimosis. Among the respondents, 53.7% stated that they used the CTR in this setting in less than 10% of cases, and 27.3% stated that they do not use CTRs in general. At the Intermountain Ocular Research Center, laboratory analysis of intraocular lenses that have spontaneously dislocated within the capsular bag, requiring explantation, has shown that in the setting of pseudoexfoliation, the presence of the CTR did not either delay or prevent the spontaneous dislocation. Similarly, neither the style nor material of the IOL implanted within the capsular bag seemed to affect spontaneous dislocation of the IOL–capsular bag complex in these patients. Pseudoexfoliation leads to a diffuse zonulopathy, which predisposes patients with this condition to spontaneous dislocation of the IOL within the capsular bag. Methods to try to prevent this using a CTR have not proven to be successful.

Alan Crandall In eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome, I use CTRs any time I see evidence of zonular weakness. For example, when I start the capsulorrhexis, I look for wrinkling of the capsule. I also look for any folds in the capsule that might appear in front of the tear, as this also suggests weakness. If the capsular bag is floppy, I have a tendency to use a CTR. I look at the anterior vitreous for another subtle sign: evidence of small pieces of cortex that have slipped through weak zonules. I estimate that I use CTRs in 30% or more of cases.

However, we must remember that a CTR can cause problems (as well as add to the cost of the procedure). Also, the timing of insertion needs to be considered.

Further reading:

Ahmed IK et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(9):1809-1813.

Lee DH et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002:28(5):843-846.

Case 12: Crowded Anterior Chamber/High Hyperopia

Q12.1 If there is no consensus among multiple formulas for a short axial length eye, what formula or method do you favor?

|

Haigis

|

19.2%

|

|

Holladay II

|

21.9%

|

|

Hoffer Q

|

46.4%

|

|

Olson

|

2.3%

|

|

RBF [radial basis function]

|

5.1%

|

|

Other

|

5.1%

|

Warren Hill The high axial hyperope presents one of the greater challenges for IOL power selection. The audience response reflects that which is generally available within biometry software and 2 decades of common practice. However, more recent IOL power selection methods such as Barrett, Olson, and Hill-RBF tend to be more accurate for these unusual eyes. Barrett and Hill-RBF also have open-access websites that allow surgeons to use them, independent of biometry software.

Dennis Lam In general, the Hoffer Q is well established for axial length (AL) <22 mm. As a routine caveat, the Holladay II, Haigis, and Hoffer Q work rather equally well for AL <20 mm. Newer concepts of effective lens position using the C constant of Olson’s formula or the “in-bounds” and “out-of-bounds” predictability of RBF formulas seem promising. Software-based computer programs like Okulix aim to reduce calculation error and ensure more reliable estimation of AL. Additional use of corneal mapping with Pentacam analysis may improve refractive outcomes regardless of the AL of the eyeball.

Q12.2 What is your approach for a brunescent cataract in a very crowded and shallow anterior chamber?

|

Phaco with generous OVD (e.g., dispersive)

|

35.8%

|

|

#1 + IV mannitol

|

41.9%

|

|

#1 after a pars plana vitreous tap

|

6.7%

|

|

Manual ECCE

|

12.8%

|

|

I would refer this patient

|

2.8%

|

Warren Hill For the majority of cases, mannitol as an IV bolus, intermittent ocular compression, and a retentive viscoelastic will allow cataract surgery to proceed without difficulty. The majority of respondents recognized the importance of the use of preoperative mannitol. My experience has been that a pars plana tap or a limited pars plana vitrectomy prior to cataract surgery is rarely necessary. I have found a pars plana tap to be useful mostly in the setting of intraoperative aqueous misdirection, after I’ve taken great care to first exclude a choroidal effusion or hemorrhage. Faced with a shallow anterior chamber, I would add that establishing multiple paracentesis sites prior to beginning the case allows access to all areas of the anterior segment. This can also be very useful for reestablishing normal anatomic relationships at any time during surgery, if the need arises.

Dennis Lam Preoperative mannitol is a useful adjunct, but phaco is best done within 20 minutes after the infusion, lest the vitreous get rehydrated. For pars plana vitreous tap, using a 21-gauge needle reduces chances of dry tap or retinal traction. Limited anterior vitrectomy (AV) using a phaco machine’s AV system with a 1-port 23-gauge self-sealing sclerotomy would be a good option. Do not remove more than 0.2 mL of vitreous lest the anterior chamber become too deep. ECCE is always an option. When in doubt, the golden dictum always stands … don’t!!! Referring instead to someone with more expertise is a good practice.

Case 13: Highly Myopic Eye

Q13.1 When the anterior capsule (AC) deepens excessively in a high myope, I would …

|

Adjust the microscope and instrument angle

|

9.8%

|

|

Lower the irrigation bottle

|

46.1%

|

|

Depress the lens with a second instrument

|

1.2%

|

|

Lift the iris with a second instrument

|

39.5%

|

|

I rarely encounter this situation

|

3.5%

|

Robert Cionni The eye with axial myopia presents several challenges. Intraoperatively, the most significant challenge is that of reverse pupillary block (RPB). Past literature referred to this phenomenon as the lens–iris diaphragm retropulsion syndrome, and recommendations included lowering the bottle height or widening the incision to increase wound leakage. More recently, we recommended a different maneuver for managing this occurrence. Simply separating the iris from the anterior capsular rim resolves this syndrome.1 Unfortunately, each time irrigation begins, the phenomenon recurs. Therefore, separating the iris from the anterior capsular rim prior to initiating irrigation flow is recommended to prevent its occurrence. An alternative approach would be placement of a pupil expansion device, such as an iris hook or Malyugin ring. It appears that nearly half of the audience is not aware of this easy maneuver to resolve RPB.

Because deepening of the IOL-bag complex can affect pseudophakic intraoperative aberrometry readings for both spherical and cylindrical powers, the surgeon should be certain that the anatomic position of the complex is normalized, as described above, prior to obtaining a pseudophakic reading.

1 Cionni R et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(5):953.

Steve Lane While the audience favored lowering the bottle for a highly myopic patient when the anterior chamber deepens excessively upon irrigation, Bob Cionni, MD, has taught us that the reason for the deepening is reverse pupillary block. This is frequently noted in highly myopic eyes and is caused by irrigation fluid getting behind the anterior capsular opening, closing (blocking) the space between the capsule and the iris such that the increase in pressure causes a posterior movement of the capsule-iris diaphragm. This causes an excessively deep anterior chamber and an increase in IOP, manifesting itself to the patient as pain. This block is most easily broken by slipping a spatula or second instrument (e.g., a chopper) between the posterior iris and anterior capsule. In eyes such as those described here, it is best to anticipate that this will occur and to proactively have a second instrument between the capsule and iris as the irrigation is initiated. This will mitigate any block and prevent any sudden discomfort for the patient.

Q13.2 What postoperative anti-inflammatory drops would you prescribe for a 54-year-old patient with an axial length of 29 mm?

|

Prednisolone acetate

|

72.8%

|

|

Loteprednol

|

7.3%

|

|

Difluprednate

|

14.0%

|

|

Topical NSAID only; no topical steroid

|

3.8%

|

|

Intraocular triamcinolone only

|

3.5%

|

Robert Cionni Prevention of postoperative inflammation is particularly important in the highly myopic eye to decrease the risk for retinal detachment. Therefore, I would recommend the use of steroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, there have been reports of a higher incidence of postoperative IOP spikes in these eyes. Most of the audience seems to agree with avoiding the most potent steroid to help decrease the risk of a pressure rise after cataract surgery. Additionally, one might consider an early postoperative evaluation 2-4 hours after surgery, as this is the time when an early postoperative IOP spike begins to develop and, if found, can be treated appropriately.

Steve Lane David Chang has reported an increased IOP response to steroids among high axial myopes (29.0 mm or more) who are young, 65 years or less.1 Therefore, these young myopes should be more carefully monitored for a postoperative steroid response following uncomplicated cataract surgery, and consideration should be given to using steroids such as loteprednol, an ester steroid that has a lower propensity to cause an increase in IOP, or possibly using no steroid at all to avoid this potential problem.

1 Chang DF et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(4):675-681.

Case 14: Post-LASIK Patients

Q14.1 What is your preference for IOL calculation in a post–hyperopic LASIK patient with no prior records?

|

I use intraoperative wavefront aberrometry (IWA) + another formula

|

14.5%

|

|

I don’t use IWA—I would favor the ASCRS Calculator

|

55.2%

|

|

I don’t use IWA—I would favor Haigis/Shammus method

|

16.5%

|

|

I don’t use IWA—I would favor another method

|

5.8%

|

|

I would refer this patient elsewhere

|

8.1%

|

Jack Holladay From the audience poll percentages, we see that less than 15% of surgeons have access to or use intraoperative refraction (ORA, Alcon; Holos, Clarity Medical Systems). We will see this percentage increase with time as cost, accuracy, and efficiency continue to improve—but also because it is especially helpful in post-refractive cases, since the actual refractive power of the cornea is used (rather than calculated from anterior surface measurements). It also incorporates the back corneal surface as well as any optical irregularity.

Scheimpflug tomography (Pentacam, Oculus; Galilei, Zeimer Ophthalmic Systems) also measures the back corneal surface and measures thousands of points over the nominal 4.5-mm pupil and can determine a more accurate equivalent K-reading (EKR) than keratometry alone. With this EKR, the double-K method, and a 5-7 variable predictor formula (Holladay 2, Olson 2, or Barrett 2), 70% of these eyes can be within 0.50 D and 95% within 1.0 D of the target.

Doug Koch This is an interesting set of responses that reflect the diversity of approaches and, frankly, the absence of a definitive approach to calculating IOL power in post-LASIK eyes. Published data show refractive accuracy within ±0.5 D in less than 70% of these eyes with any method, including intraoperative aberrometry.

I believe that regression methods that rely on averages from prior patient outcomes have maxed out in their accuracy, highlighting our need to be able to measure each patient’s anterior and posterior corneal power accurately. This need is not restricted to post-LASIK eyes but pertains to all patients—certainly those with more complex corneal curvatures (e.g., keratoconus, post–penetrating keratoplasty, post–Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty, etc.) but also those with “normal” corneas whose anterior-posterior curvature ratio differs widely from the assumed ratio used to estimate total corneal power.

Q14.2 When would you be willing to implant a diffractive multifocal IOL in a post-LASIK patient?

|

I never implant multifocal IOLs

|

27.4%

|

|

I implant multifocal IOLs, but never in post-LASIK eyes

|

41.7%

|

|

Only if the patient insists because I generally discourage multifocal IOLs in these eyes

|

16.3%

|

|

I would, assuming that the patient was otherwise a good candidate

|

10.6%

|

|

I would refer this patient

|

4.0%

|

Jack Holladay Diffractive multifocal IOLs are known to cause a reduction in contrast sensitivity of 30% and in best spectacle-corrected visual acuity of 1 line, and they are associated with halos and glare that are noticeable by some patients. If the patient has poor corneal optics or reduced macular function, a further reduction in visual performance occurs and often results in an unhappy patient.

We have quantitative measures of corneal optics, where topographers/tomographers provide a higher-order (HO) root-mean-square (RMS) corneal wavefront error over a 6-mm zone. A study by G.J. McCormick and colleagues in 20051 showed the average HO RMS wavefront error for symptomatic patients was 1.31 ± 0.58 μm. This was an average of 3.46 times greater than the average magnitude of normal preoperative eyes (0.38 ± 0.14 μm) and an average of 2.3 times greater than the average magnitude of asymptomatic successful postoperative conventional LASIK eyes (0.58 ± 0.21 μm) over a 6-mm pupil. Any patient with an HO RMS corneal wavefront error above 0.50 μm over a 6-mm zone is not a good candidate for a diffractive multifocal IOL, regardless of the cause.

1 McCormick GJ et al. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(10):1699-1709.

Doug Koch Roughly 25% of respondents would implant multifocal IOLs in post-LASIK eyes. Personally, I have removed many multifocal IOLs from eyes that had previously undergone LASIK or PRK. All had irregular corneal astigmatism. I find monovision to be a valuable approach in many of these patients, providing extended range of vision while preserving quality of vision. The multifocality of the cornea can be beneficial with this approach.

There clearly is a subset of post-LASIK eyes that are candidates, presumably those with very regular anterior corneal curvature. What is unknown is how we should select these patients. Do we look at corneal aberrations? If so, which ones individually or in combination are most predictive?

Two new categories of IOLs may expand opportunities: extended range of focus and heavily distance-dominant low-add multifocal IOLs. Further studies are needed to understand their role in these patients.

Case 15: Temporal Negative Dysphotopsia 6 Months Out

Q15.1 How would you manage a patient who is miserable with temporal negative dysphotopsia (6 months following implantation of a single-piece acrylic IOL with an overlapping capsulorrhexis)?

|

YAG the edge of the capsulorrhexis

|

24.6%

|

|

Implant a piggyback IOL in the sulcus

|

7.4%

|

|

Reverse optic capture of the single-piece acrylic IOL

|

25.8%

|

|

Exchange the IOL

|

12.5%

|

|

Other

|

6.3%

|

|

I would refer this patient elsewhere

|

23.4%

|

Bonnie Henderson The management of negative dysphotopsia (ND) is challenging because the etiology is multifactorial. In a review of the literature of negative dysphotopsia,1 all the options above have been reported to be successful but also to be unsuccessful. Personally, I believe the 2 best options are to perform reverse optic capture of the IOL or to implant a piggyback sulcus IOL. If the original surgery was more than a year ago or if the capsule opening will not support an optic capture, I implant a sulcus silicone 3-piece IOL with rounded anterior edges. This technique is usually helpful but often does not eradicate the symptoms completely. Many patients find that the symptoms have decreased about 75% and are less bothersome, but they can still find the ND shadow under certain conditions.

Another possible solution to prevent ND symptoms in patients with a 1-piece acrylic IOL is to place the optic-haptic junction inferotemporally to decrease the amount of available optic edge. Light striking a square optic edge appears to be one of the many causes of ND. Therefore, placing the junction in the inferotemporal position limits the amount of edge in that location where light enters the eye. In the other positions, light is obstructed by the lids. Decreasing the amount of available edge by one-third has been shown to decrease the ND symptoms significantly in the early postoperative period.2

1 Henderson BA et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(10):2291-2312.

2 Henderson BA et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(10):1449-1455.

Sam Masket While negative dysphotopsia is not rare early after cataract surgery, the great majority of patients improve over time, most likely due to neuroadaptation. Those cases that persist beyond 6 months tend to be chronic, and the patients are generally frustrated and desirous of help.

At the outset, I have a lengthy conversation with the patient about the enigma of the condition, including the fact that it occurs only with what is considered to be anatomically “perfect” surgery, and I discuss our experience with surgical approaches. Typically, the patient has seen several other ophthalmologists who have not been sympathetic to the problem, and the patient must be reassured that he or she is sane and indeed has a debilitating problem. Unfortunately, in many such cases, an unnecessary and ineffective posterior capsulotomy has been performed in an attempt to alleviate symptoms.

Although always a worthy consideration, nonsurgical means for dealing with symptomatic chronic ND often fail. Those include pharmacologic mydriasis (which may induce glare and aesthetic deformity) and spectacles with thick temple pieces (patients often desire freedom from glasses). That said, I generally offer those methods, albeit with little success.