This article is from September 2005 and may contain outdated material.

There’s a running joke among researchers who measure patient adherence to prescription drug regimens. Ask a patient when he ran out of a drug, and he’ll say, “Last night.” Ask again during the same visit, and he’ll say, “A few weeks ago.” The third time, he’ll reply, “Last month.”

Patients sometimes have trouble admitting the truth. “They want to please the doctor,” said James C. Tsai, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology, director of glaucoma division, Columbia University. “It’s like telling the dentist that you floss every day.” Patients claim they take their drugs more than they really do. And even those who do take their medications as prescribed are indistinguishable from those who do not.

How Big Is Nonadherence?

These unfortunate truths were first reported in a pioneering glaucoma compliance study published in 1986 by Michael A. Kass, MD.¹

In the years since Dr. Kass first attached an electronic monitor to a medicine bottle and discovered a huge discrepancy between self-reported adherence (100 percent) and actual (76 percent), the problem hasn’t gone away. In fact, Paul P. Lee, MD, JD, professor of ophthalmology at Duke University, said that it has taken on greater urgency in light of the lessons learned from a series of major, randomized clinical trials, including CIGTS, AGIS, OHTS and EMGT.

“We now know that lowering the eye pressure has been shown in the trials to be an effective means of preventing progression of vision loss due to glaucoma. We know we can lower the pressure with medications,” said Dr. Lee. “So the use of medications on a consistent basis is important to prevent vision loss.”

But patients don’t consistently take their medications. Compliance, or the currently-preferred term, adherence (see sidebar “You Say Adherence . . .”), is a significant problem. Over the years, nonadherence rates of greater than 25 percent have been measured through patient self-reporting, electronic monitoring, and prescription refill reviews.

In a meta-analysis of 569 studies that looked at prescriptions by nonpsychiatric physicians, the average nonadherence rate was 25 percent. It was even greater—more than 30 percent—for silent conditions like diabetes and pulmonary disease, which require long-term and complex regimens.²

|

|

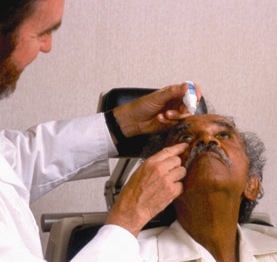

Clinician instructs patient on how to

administer glaucoma medication.

|

Why Patients Don’t Follow Their Plan

And so researchers continue to plumb the depths, searching for explanations to this self-defeating behavior. “We’ve got so many great medications out there, but how do you get the patient to take the drops correctly?” said Dr. Tsai. To answer that question, he turned to diabetes researchers, who have been at the forefront of the field. “The researchers don’t see the patients as being bad,” Dr. Tsai explained. “They just see barriers to adherence.” On their advice he created a taxonomy, or systematic classification, of all the barriers to adherence.

Through a series of open-ended and specific questions, Dr. Tsai and colleagues described 71 unique reasons for nonadherence, culled from interviews with 48 patients with glaucoma. The number of barriers was higher than expected.

Patients reported the typical reasons, including problems with drop administration, following directions, bottle design, cost and forgetfulness. But nearly 50 percent of the barriers were “situational/environmental,” instances in which some other factors come into play. For example, the patient travels to Europe, forgets his drops and has no way to refill them. Or a loved one is in the hospital and the glaucoma patient feels guilty focusing on her own health.

“Our major finding,” said Dr. Tsai, “was that solutions are going to have to become more innovative and individualized. It’s likely to be different for each patient.”

How to Improve Adherence?

Make it a shared problem. When addressing patients, Dr. Tsai avoids confrontational questions. He begins by saying: “I myself have difficulty taking a multivitamin every day. Do you have difficulty taking a glaucoma drop?” That, he explained, “takes the emphasis off of them doing something wrong. It makes it seem like this is a common problem that you understand. The approach makes the patient an active part of the process. After all, it’s their disease.” He added that once you identify the barriers, you can ask: “How do you think we can help you?”

Ask open-ended questions. Gail F. Schwartz, MD, a private practitioner and assistant professor of ophthalmology at both Wilmer Eye Institute and the University of Maryland also prefers an open-ended question approach. (See sidebar, “Tips for Better Adherence.”) If the patient’s pressure does not seem to be where it should be, consider repeating the questions, because changes in the answer—as the joke suggests—are common, Dr. Schwartz said.

Think for the long term. Dr. Schwartz said that optimal treatment requires a long-running conversation between the doctor and patient to reinforce the benefits of ocular hypotensive therapy and follow-up visits. “Be clear that this is a long-term plan. I can’t tell you how many patients say they finished the bottle and that was it.”

Simplicity wins. Finally, Dr. Schwartz recommends “the simplest feasible medication regimen that will meet the patient’s needs.”

That advice was underscored by Alan L. Robin, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Maryland and associate professor of ophthalmology at Johns Hopkins, who found that adding a second drug to a patient’s therapeutic regimen might affect a patient’s adherence to the first drug.³ In a retrospective study, Dr. Robin examined prescription-refill rates from the records of nearly 5,000 patients who were started on latanoprost (Xalatan). More than 3,000 of those patients remained on monotherapy, while a second drug was added to the regimen of 1,784 patients.

The adherence rate for both groups was the same until the addition of a second drug, said Dr. Robin. Once the second drug was prescribed, approximately one-fourth of those patients increased the time between refills by two weeks.

Dr. Robin also found that the length of time on the drug, which is often cited as a barrier, didn’t matter. What did matter was the addition of the second drug. “The more medications you use, the less likely you are to comply and adhere to therapy,” he said.

In a different study, Betsy Sleath, PhD, RPH, associate professor of pharmaceutical policy and evaluative sciences at the University of North Carolina, found that 60 percent of patients on two or more glaucoma medications reported one or more problems with taking their medications. “I think it is very important that the more medications they were on, the more trouble they had remembering to take them,” said Dr. Sleath.

Dr. Robin sees combination drug formulations as one solution. He noted that four different drugs, each combining a different prostaglandin with timolol, are currently pending before the FDA.

Acknowledging the problem is key. Dr. Robin said that for too long, the prevailing attitude has been that “adherence or compliance applies to everybody else’s patients, but not mine,” he said. “The bottom line is: It really happens all over. It’s a universal problem.”

_______________________________

1 Amer J Ophthalmol 1986;101:524–530.

2 DiMatteo, M. R. Med Care 2004;42:200–209.

3 Ophthalmology 2005;112:863–868.

_______________________________

Dr. Lee is a consultant for and receives research funding from Allergan and Pfizer. Dr. Robin is a consultant to Alcon, Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Schwartz receives research funding from Pfizer, Allergan, Alcon, Merck and Santen. Dr. Sleath is a consultant for Alcon. Dr. Tsai receives research funding from and is a consultant to Alcon and Allergan.

You Say “Adherence...”

In the lexicon of researchers who study whether patients stick to a prescription drug regimen, adherence has replaced compliance. The switch is more than semantic.

“Compliance, the original term, implied that the patient does what the doctor orders,” explained Dr. Sleath, who studies the social aspects of medication use. Adherence, which appears later in the literature, implies active patient involvement and a doctor-patient partnership, she said. “You and the doctor decide what you’re going to do and you do it together.”

Persistence, a term that appears frequently in the compliance/adherence literature, is the opposite of discontinuation. It means staying on the medication for the long term.

|

Tips for Better Adherence

Here are some tips from the experts on how to keep patients on track.

Minimize wastage. Have a technician observe how the patient instills drops by practicing with artificial tears.

Ask open-ended questions. What problems or concerns do you have with the medications? When did you last take your drops?

Consider repeating the questions. This is especially important if the IOP isn’t where it should be.

Help patients schedule drops. The prescription should be built into a daily routine, such as with morning coffee or at tooth-brushing time.

Advise patients to keep a spare. An extra bottle at the workplace may help.

Provide the patient with an eye drop chart. Then keep a copy in the patient record.

Don’t assume the pharmacist will explain how to use the medication. And don’t assume that patients can read and understand the instructions.

Determine if cost is an issue. If so, give patients information on pharmaceutical company assistance programs.

|