This article is from September 2012 and may contain outdated material.

For patients in advanced stages of glaucoma who need low intraocular pressure (IOP), trabeculectomy and tube-shunt surgery remain the mainstay therapies. Both are associated with similar reductions overall in IOP, and both necessitate about the same amount of reliance on supplemental medical therapy after surgery. However, a recent study comparing the two procedures among patients who had previously undergone cataract or trabeculectomy surgery has shown that, although both are effective in controlling IOP, tube-shunt surgery has a higher success rate.1 So is it time to take a new look at tubes? Yes, say experts in the field.

TVT Challenges Assumptions

Traditionally, trabeculectomy has been considered the gold standard glaucoma procedure—the first choice for management of glaucoma patients who need surgery. In contrast, tube-shunt surgery generally has been used as a primary approach only for more complex cases, such as neovascular glaucoma.

Recent results from the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) Study, a multicenter randomized clinical trial that compared tube-shunt surgery with trabeculectomy for glaucoma in patients who had undergone cataract surgery or failed trabeculectomy, show that tube shunts are a powerful tool in the fight against glaucoma—with a higher surgical success rate, lower complication rate, and fewer repeat surgeries five years after the procedure compared with trabeculectomy.1,2

“The TVT Study does not demonstrate clear superiority of one procedure over the other,” said Steven J. Gedde, MD, a chairman of the study and professor of ophthalmology and residency program director at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. “However, it does show that tube shunts are a very viable surgical option in this patient group.” (The group excluded patients with refractory glaucomas—including neovascular glaucoma; uveitic glaucoma; and glaucoma associated with iridocorneal endothelial syndrome, epithelial downgrowth, or fibrous downgrowth—for whom tubes may normally be preferred.) The TVT group is at lower risk of surgical failure than the more difficult patients that have traditionally undergone tube-shunt implantation, he said.

These findings coincide with an increase in the use of shunts.3 Some ophthalmologists are suggesting that, in certain circumstances, sooner is better than later for using the drainage devices, a shift that is reflected in changing practice patterns.4

“When the TVT trial began, many of us were starting to get away from trying a second trabeculectomy after the first one failed,” said Cynthia Mattox, MD, vice chair for clinical services in the department of ophthalmology at Tufts University and director of the glaucoma and cataract service at the New England Eye Center in Boston. “The results of the TVT reassure surgeons that using tube-shunt surgery after the first trabeculectomy has failed, rather than systematically performing a second trab, is a good alternative,” she said.

Specifically, the TVT study showed that, among patients who had previous surgery, those who received tube shunts were more likely than trabeculectomy patients to show adequate and sustained IOP reduction in the long term. In addition, the failure rate for trabeculectomy was more than three times that of tube-shunt surgery during the first year of follow-up.5 The differences appear to persist: At the three-year mark, the cumulative probability of failure was 15.1 percent in the tube group and 30.7 percent in the trabeculectomy group.6 By five years, it was 29.8 percent and 46.9 percent, respectively.1

|

|

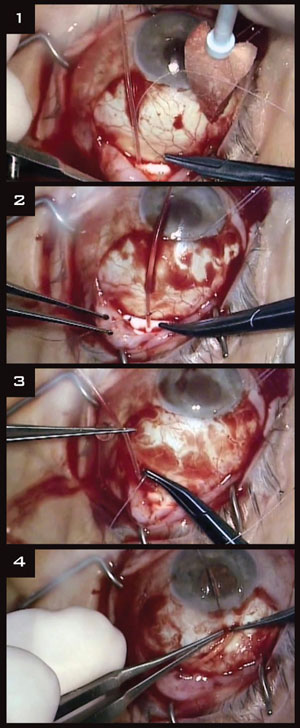

(1) The Baerveldt implant is sutured between rectus muscles. (2) The tube is ligated. (3)Venting slits allow limited flow until the ligature dissolves. (4) Then 2 to 3 mm of the tube is placed into the anterior chamber.

|

Pros and Cons for Tubes

Of course, outcomes are a key factor in determining choice of procedure, but several other aspects of tube surgery are worth taking into consideration.

It’s a standardized procedure. “Tube-shunt surgery is, in many ways, a very standardized procedure. In fact, I use the same surgical technique in almost every patient,” said Dr. Gedde. “In contrast, there is a lot more finesse involved in performing a trabeculectomy.” For example, the dosage of antifibrotic agent and number of scleral flap sutures “are variables that need to be tailored to each individual patient,” he said. He also characterizes tube-shunt surgery as “more forgiving.”

Postop care is relatively easy. An advantage of tube-shunt surgery over trabeculectomy, Dr. Mattox said, is that it usually has a “less burdensome postoperative care regimen.” In some situations, tube shunts may be an appropriate first-line surgical option rather than trabeculectomy, she said. For example, “We have some patients from a long way away,” Dr. Mattox explained, “who express difficulty in making return trips.” When that occurs, she may suggest that they consider tubes. In addition, tube-shunt surgery might be appropriate for any patient who would have problems managing the vigilant postsurgical care required for trabeculectomy.

There’s a learning curve—trab is a habit. On the other hand, one factor limiting adoption may be a learning curve, said Brian A. Francis, MD, a contributing investigator in the TVT study and associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Ophthalmologists are more familiar with trabeculectomy and are accustomed to considering it as the initial surgery for glaucoma. He added that doctors think trabeculectomy first partly because it doesn’t preclude future shunt placement in the same patient.

Options are limited if tubes fail. In contrast with trabeculectomy, “The biggest downside of a primary tube shunt is that, if it fails, the choices are more limited and include a second, inferiorly placed tube or cyclophotocoagulation,” said Dr. Mattox. However, “When a previously successful trabeculectomy fails, there are several choices, including an in-office mitomycin C–augmented needling revision, which can resurrect a trabeculectomy, even years later.”

Patient may have concerns about tubes. Dr. Francis has encountered some resistance from patients “who don’t really like the idea of [what they perceive as] hardware in their eye.” Outcome data from the TVT Study may help quell such reservations, he said. Dr. Mattox has heard similar concerns—that a tube is a foreign object, plastic and unnatural, and “it’s always going to be in there.” Patient education is key. But, apart from patients’ opinions, it remains to be seen whether erosion or extrusion of the implants will become more of a problem as more tubes are used earlier in the course of glaucoma, Dr. Mattox noted.

Long-term results are unknown. A study of the long-term results of primary trabeculectomy versus primary tube shunts is still under way. “Until the results of the primary comparison study are out, I’m not ready to jump on the bandwagon of primary tubes for my initial filtering surgery in all cases,” Dr. Mattox said. “I like my trabeculectomies and the fact that I have more options down the line.”

Other Surgical Techniques

Surgery for both trabeculectomy and tube shunts is labor intensive, so the quest for newer devices and procedures is continuing. Currently, there is interest in less invasive angle-based surgeries that can be combined with cataract surgery. These procedures may lead to earlier surgical management of glaucoma, in the mild and moderate stages of disease, once more is known about their long-term success and safety.7

So far, though, there is no universal go-to approach, said Dr. Francis. “It takes looking carefully at an individual patient to determine treatment,” he said. “That has always been the case.”

___________________________

1 Gedde SJ et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):789-803.

2 Gedde SJ et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):804-814.

3 Ramulu PY et al. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2265-2270.

4 Desai MA et al. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2011;42(3):202-208.

5 Gedde SJ et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(1):9-22.

6 Gedde SJ et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(5):670-678.

7 Gedde SJ et al. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(2):118-126.

___________________________

Drs. Francis, Gedde, and Mattox report no related financial interests.