By Rick Roe, MD, MHS, Caroline Fisher, MD, and Emmett T. Cunningham JR., MD, PHD, MPH

Edited By Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from May 2006 and may contain outdated material.

Michael Chu* had just finished another busy day selling insurance and was on his way home when he began noticing blurry vision and floaters in his right eye. He shrugged the symptoms off for the night, but after they worsened the following morning he decided to see his ophthalmologist. He was diagnosed with a possible retinal hole and was referred to our eye clinic for evaluation.

We Get a Look

A note from the outside ophthalmologist described a small hole in the inferotemporal periphery of Mr. Chu’s right eye with surrounding hemorrhage. Mr. Chu had high myopia, but no history of trauma. He told us that there was no pain, photophobia or photopsia. He was not taking any medications. His past medical and surgical histories were otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, BCVA was 20/60 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left eye. There was no afferent pupillary defect, and his IOP was 15 mmHg bilaterally. His anterior segment examination was unremarkable.

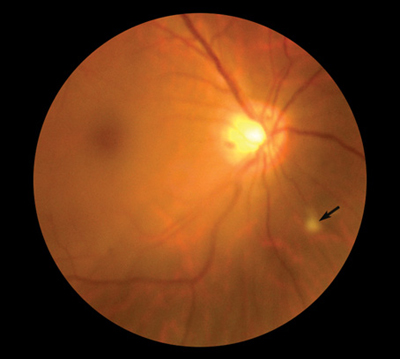

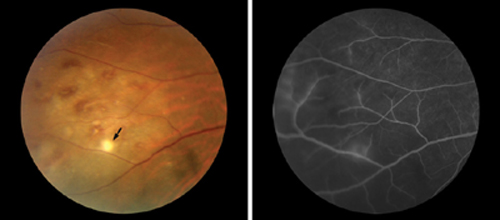

On dilated fundus examination, we noted that Mr. Chu had a 1+ vitritis in each eye and several small discrete areas of retinal whitening, including one nasal to the disc (Fig. 1). There was another, larger spot in the inferotemporal periphery of the right eye with surrounding intraretinal hemorrhages (Fig. 2A). In the left eye, the patient was noted to have a small white dot just superior to the fovea. No retinal holes were found on depressed examination of the retinal periphery.

Fluorescein angiography revealed scattered areas of vasculitis and capillary nonperfusion in the inferotemporal periphery on the right (Fig. 2B). A laboratory workup was initiated, including serum RPR (rapid plasma reagin), FTA-Abs (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption), ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme), CBC (complete blood count), HIV titer and Lyme titer. All results were either negative or within normal limits. A chest x-ray and PPD (purified protein derivative) were also ordered and were normal.

Clinically, our patient had an acute bilateral nongranulomatous uveitis associated with an occlusive retinal vasculitis and patchy retinal infiltrates. The differential diagnosis included syphilis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, viral retinitis and Behçet’s disease.

|

|

(1) When we performed a dilated fundus examination, we found that Mr. Chu had moderate vitreous inflammation. We also noticed a small area of retinal whitening inferonasal to the optic disc (arrow).

|

We Make a Diagnosis

Syphilis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease and sarcoidosis were effectively ruled out by laboratory investigations and radiologic testing.

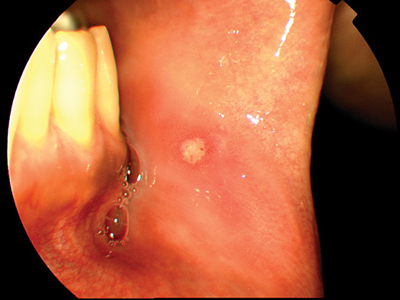

Upon further questioning, the patient admitted to recurrent fevers over the past several years with associated “mouth sores.” On physical examination, the patient was noted to have an aphthous mouth ulcer (Fig. 3) and several acne-iform skin lesions on his back.

With this additional information, the patient was diagnosed with Behçet’s disease, and he was subsequently started on 60 milligrams of oral prednisone daily with a slow taper. The patient responded well to the medications with decreased vitreous inflammation and resolution of his retinal hemorrhages and infiltrates. At his most recent visit, his vision had improved to 20/20 bilaterally.

|

|

(2) These color (A) and fluorescein angiographic (B) photographs of the inferotemporal periphery of the right eye show scattered intraretinal hemorrhages, a small area of retinal whitening (arrow) and active vasculitis.

|

Pathology and Incidence

First described by Turkish physician Huluci Behçet and Adamantiades from Greece in the 1930s, Behçet’s disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of systemic vasculitis, orogenital aphthous ulcers, skin lesions and panuveitis.¹ The cause of Behçet’s disease is still unknown, but the underlying pathology is an obliterative and necrotizing vasculitis in multiple organ systems, primarily involving mucosal tracts.

Most cases originate from the so-called ancient Silk Road—the area of the world stretching from Japan in the Far East to Turkey and Iran in the Middle East, where the prevalence can be as high as 42 per 10,000. In the United Kingdom, by contrast, the disease is rare, affecting only one to two per million. The idea that certain patients are susceptible to Behçet’s disease is supported by its increased association with HLA-B51.

|

|

(3) After further questioning, the patient told us that, for several years, he had been suffering recurrent fevers and associated “mouth sores.”

|

Ocular Signs of the Disease

The frequency of ocular involvement in Behçet’s disease is about 70 percent, and uveitis can be the first presenting sign in approximately 10 percent of cases. It commonly involves both eyes but can be unilateral in a minority of patients. Blindness occurs in up to 15 percent of patients affected by this disorder.2

Ocular signs of Behçet’s disease typically reflect a panuveitis, with a variable anterior uveitis with occasional accompanying hypopyon. However, the teaching that Behçet’s disease is synonymous with an anterior hypopyon should be accepted with caution since studies have consistently shown that this finding is fairly uncommon.

The principal causes of visual loss in Behçet’s disease are macular infarction and branch macular vein occlusions producing either macular edema or ischemia. Some patients may exhibit a vitritis as with Mr. Chu, but nearly all patients with Behçet’s disease present with a retinal vasculitis. This is often manifested by the presence of intraretinal hemorrhages and areas of patchy retinitis as observed in Mr. Chu. In fact, these patchy white retinal infiltrates are believed by some to be highly suggestive of this disorder and are often easily distinguished from cotton-wool spots by their round or oval shape and by their occurrence in the periphery, where the nerve fiber layer is too thin for cotton-wool spots to occur.3

Treatment

Early control of ocular inflammation in Behçet’s disease is best achieved with local or systemic corticosteroids. In most patients, however, noncorticosteroid immunosuppressive agents are required to achieve long-term control. Once the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease is established, it is important to involve a rheumatologist in the overall care and management of the patient. Recent studies have suggested that anti-TNF-alpha agents, such as infliximab or etanercept, as well as interferon alpha-2a may be promising in the treatment of severe refractory disease.4,5

___________________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________________

1 Verity, D. H. et al. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:1175–1183.

2 Tugal-Tutkun, I. et al. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;138:373–380.

3 Dominguez, L. N. and A. R. Irvine. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1997;95:367–382 and 382–386 (discussion).

4 Lindstedt, E. W. et al. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:533–536.

5 Kotter, I. et al. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87: 423–431.

___________________________________

Drs. Roe and Fisher are finishing their ophthalmology residencies and Dr. Cunningham is clinical professor of ophthalmology and director of the uveitis clinic. All are at New York University School of Medicine.