By Lori Baker-Schena, MBA, EdD, Contributing Writer, interviewing Gerrit R.J. Melles, MD, PhD, Francis W. Price Jr., MD, and Mark A. Terry, MD

Download PDF

Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) appears to be gaining acceptance with cornea surgeons for treatment of patients with corneal endothelial dysfunction.

In DMEK, the endothelium and Descemet membrane (DM) are delivered into the anterior chamber in the form of a scroll that must be unfolded. A number of studies indicate that the procedure offers rapid and predictable visual recovery.1 And compared with other keratoplasty procedures, it offers a number of benefits, including better quality of vision and a reduced risk of immunologic graft rejection.1

Yet cornea surgeons have been slow to adopt the procedure, acknowledged Francis W. Price Jr., MD, of Price Vision Group in Indianapolis. However, he said, “we [now] appear to be at the tipping point where adoption will be more rapid Many training programs are now doing DMEK, and the younger generation of cornea specialists coming out should be trained and familiar” with it.

Gaining Traction

Gerrit R.J. Melles, MD, PhD, agreed that the tide of acceptance has shifted in the last few years, which he attributed to improvements in the surgical procedure and graft preparation techniques.

“Given the clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction, DMEK has been gaining traction with ophthalmologists all over the world,” said Dr. Melles, of the Netherlands Institute for Innovative Ocular Surgery in Rotterdam. “Currently, DMEK may be feasible for most cornea surgeons in any clinical setting and at a relatively low cost.”

Follow the numbers. A recent Ophthalmic Technology Assessment (OTA) underscores this shift, noting a 64% increase in DMEK procedures from 2014 to 2015.1 In comparison, the OTA found a 4.1% decrease in the number of an earlier EK iteration, DSEK (Descemet stripping EK), since 2013.

And the number of DMEK procedures is doubling every year, according to Mark A. Terry, MD, as the technique continues to be standardized and refined. “I tell surgeons that they should learn to perform DMEK, first focusing on routine cases without other confounding variables,” said Dr. Terry, of the Devers Eye Institute in Portland, Oregon.

|

|

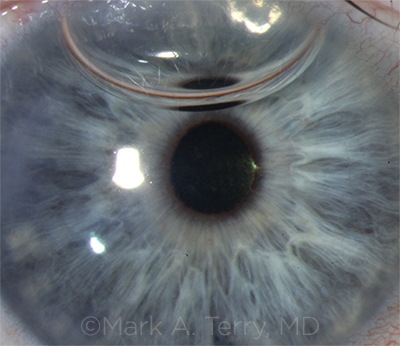

SIX DAYS OUT. A DMEK graft 6 days after surgery, the first DMEK procedure to be performed by a cornea fellow. At this point, the patient’s vision was 20/30 without correction.

|

Bumpy Road to Acceptance

DMEK was first described by Dr. Melles in 2006.2 As the technique was perfected over the next few years, cornea surgeons reported that they were achieving 20/20 and 20/15 in more than 50% of eyes—and that their patients were experiencing a quicker recovery time.

Game changer. In 2012, Dr. Price and his colleagues found that patients undergoing DMEK were significantly less likely to experience a rejection episode within 2 years after surgery compared with DSEK and PK for similar indications using the same corticosteroid regimen.3

These results prompted Dr. Price to revisit his corticosteroid dosing regimen. In a prospective study, he compared intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation and graft rejection with loteprednol etabonate 0.5% gel and prednisolone acetate 1% solution after DMEK. The 2 medications proved equally effective in preventing immunologic rejection episodes (none occurred), and IOP elevation was twice as likely in the prednisolone-treated eyes.4

“This was a game changer for us, allowing for a decreased dosage of topical steroid,” Dr. Price said.

Key challenges. Despite these and other favorable study results, barriers to DMEK acceptance remained.

Tissue prep. This has been one of the biggest stumbling blocks. “I had been stripping my own DMEK tissue since 2009,” Dr. Terry said. “However, surgeons were concerned with the time it took to prepare tissue in the OR, as well as the very real risk of damaging donor tissue.”

Dr. Terry and his colleagues overcame this hurdle by working with the local eye bank to provide prestripped donor tissue, which removed the risk for the surgeon without increasing the possibility of graft failure or re-bubbling compared to surgeon-prepared tissue.5

Graft orientation. The next barrier for surgeons was to confirm the correct orientation of the DM graft. Dr. Terry worked with the eye bank to perform a novel stromal-sided S-stamp preparation, which safely eliminated upside-down graft implantation.6

Graft delivery. “Even with these developments, surgeons were reluctant to adopt DMEK,” Dr. Terry said. “They still had to stain, trephinate, and load the graft into an injector, which entailed time and some risk.” Once again, he turned to the eye bank, working on the next advance, in which the prestripped, prestamped donor cornea is also preloaded into a glass injector, ready for injection into the patient’s eye.7

Learning curve. Experienced EK surgeons have been reluctant to adopt the newer technique, given their comfort level and success rate with DSEK (and its automated variation, DSAEK) as well as the technical challenges posed by DMEK. But this is beginning to change, driven by study results and what the OTA described as “extensive DMEK educational and skill transfer courses.”1

What impact does the learning curve have on outcomes? Dr. Melles recently published a multicenter study on approximately 2,500 DMEK eyes performed by different surgeons all over the world, looking at outcomes and complications.8

“Technique standardization and surgical experience seem to have a strong effect on the rate of postoperative complications and have especially contributed to fewer graft detachments,” he said. “However, experience does not seem to influence postoperative visual acuity outcomes.”

Complications. According to the OTA, the “types of complications during and after DMEK are similar to those encountered with DSEK.”1 The most common complication has been partial graft detachment; other complications have included graft failure, IOP rise, cystoid macular edema, and endothelial cell loss.1

Patient selection. DMEK can be performed concurrently with cataract surgery and in patients with previous trabeculectomy or glaucoma drainage devices.1

However, for eyes with large iris defects, aphakia, or significant anterior synechia and scarring, Dr. Price is among those who use DSAEK/DSEK.

The Historical Perspective

DMEK is a variation of EK, a surgical alternative to full-thickness cornea transplant designed to selectively replace only the diseased layer of the cornea, leaving the healthy tissue intact.

Dr. Terry distinctly remembers when he stumbled upon a unique lamellar technique back in 1998 while conducting a literature review.

“I had been doing penetrating keratoplasty (PK) since 1981 and had achieved results as good as anyone,” Dr. Terry recalled. “However, the inherent results of PK are relatively poor in terms of visual outcome, poorly healing wounds, and rejection risks. I knew there had to be a better alternative.”

As an author for the 25th anniversary issue of Cornea, Dr. Terry was asked by then editor Mark J. Mannis, MD, to write a review article on lamellar keratoplasty. During his literature search, Dr. Terry found a laboratory article in which Dr. Melles reported results from his work with eye bank eyes and 1 monkey. In the study, Dr. Melles dissected out the posterior cornea and replaced it with posterior stroma and endothelium from donor corneal tissue.1 The self-adherent graft required no sutures and could be held in place with an air bubble.

DLEK. “Posterior lamellar keratoplasty (PLK) was the inspiration for me,” Dr. Terry said. “I made some key modifications to make it easier, designed my own instruments and over 1 year developed a modified procedure that I named deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK).

“With this new name, I wanted to emphasize the ‘selective endothelial replacement’ of this procedure, which would open up an entire new category of surgery and surgical codes for EK,” Dr. Terry said. “I performed the first EK surgery in the United States in March of 2000 with fast visual recovery compared to PK and presented the case at the Academy meeting that year. Subsequent patients also did well with no complications, and we published their results in 2001.”2

Several advances have helped make the procedure even easier and more reproducible. These include descemetorhexis, which replaced manual dissection of the posterior stroma with removal of the DM,3 and the use of the automated microkeratome instead of manual dissection of donor tissue.4

DSEK. Dr. Price performed the first Descement stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) procedure in the United States in 2003 and then reported the first series of DSEK in 200 eyes in the United States.5 Dr. Terry helped popularize the technique by developing a standardized approach6 and by working with U.S. eye banks to precut donor tissue for transplantation.

___________________________

1 Melles GR et al. Cornea. 1998;17(6):618-626.

2 Terry MA, Ousley PJ. Cornea. 2001;20(3):239-243.

3 Melles GR et al. Cornea. 2004;23(3):286-288.

4 Gorovoy MS. Cornea 2006;25(8):886-889.

5 Price FW Jr., Price MO. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(3):411-418.

6 Terry MA et al. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1179-1186.

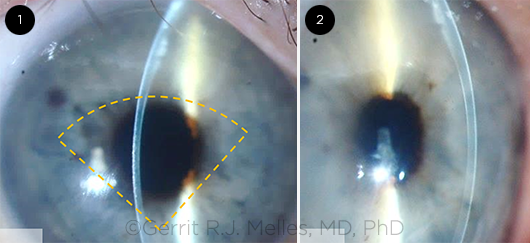

QUARTER-DMEK. Slit-lamp images taken 3 months after Quarter- DMEK. The orange dashed lines (1) outline the approximate location of the graft. Note a centrally thin cornea and some remnant edema in the superior quadrant (2).

|

What’s Next?

Research efforts on deck include the following.

Quarter-DMEK. Dr. Melles and his team are currently evaluating “Quarter-DMEK” for the treatment of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy.9 This hybrid technique marries DMEK, which provides fast visual recovery, to DM endothelial transfer (DMET), which allows a cornea to clear through donor and/or host endothelial cell migration.

“With Quarter-DMEK, a smaller graft is used to cover the central cornea, to provide fast visual recovery by the presence of donor endothelium within the visual axis, while stimulating host endothelial cells to bridge the area between the edge of the descemetorhexis and the graft itself,” Dr. Melles said.

He noted the added benefit of Quarter-DMEK is that 4 grafts may be prepared from 1 donor eye, which would potentially quadruple the number of transplants from a given donor pool.

Use of glaucoma drugs. Dr. Terry cited projects under study in which the DM is stripped and the eye is treated with the glaucoma medication ripasudil. This stimulates endothelial cells, thus possibly eliminating the need for a corneal transplant altogether.10 (See the December 2017 EyeNet cover story for more about this.)

Dr. Price’s center has recently begun a placebo-controlled randomized study to see if one of these glaucoma drugs, a rho-kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, can block the IOP increase seen with topical corticosteroids as well if it has any effect on the donor and recipient cornea.

Evaluation of color perception. Dr. Price’s team also has discovered that color discernment usually improves after DMEK in patients with Fuchs,11 an outcome he hypothesized may be related to the removal of the guttae associated with the condition.

___________________________

1 Deng SX et al. Ophthalmology. Published online Sept. 16, 2017.

2 Melles GR et al. Cornea. 2006;25(8):987-990.

3 Anshu A et al. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(10):536-540.

4 Price MO et al. Cornea. 2015;34(8):853-858.

5 Terry MA et al. Cornea 2015;34(8):845-852.

6 Veldman PB et al. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(1):161-164.

7 Tran KD et al. Cornea. 2017;36(4):484-490.

8 Oellerich S et al. Cornea. 2017;36(12):1467-1476.

9 Müller TM et al. Cornea. 2017;36(1):104-107.

10 Moloney G et al. Cornea. 2017;36(12):642-648.

11 Price DA et al. Cornea. 2016;35(8):1045-1048.

___________________________

Dr. Melles is director of the Netherlands Institute for Innovative Ocular Surgery (NIIOS), the Melles Cornea Clinic, and the Amnitrans EyeBank, all in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. He is also director of NIIOS USA, in San Diego. Relevant financial disclosures: DORC International BV/Dutch Ophthalmic USA: C; SurgiCube International: C.

Dr. Price practices with Price Vision Group and is the founder of the Cornea Research Foundation of America, both in Indianapolis. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Terry is director of Cornea Services at Devers Eye Institute and professor of clinical ophthalmology at Oregon Health Science & University, both in Portland. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

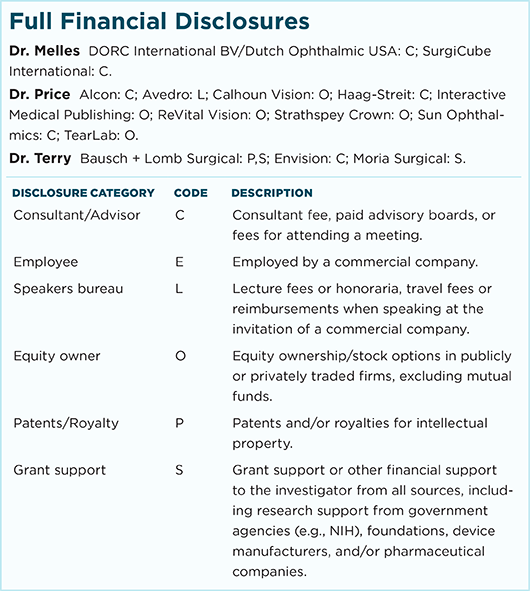

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.