This article is from September 2012 and may contain outdated material.

During the past decade, endothelial keratoplasty (EK) has supplanted penetrating keratoplasty (PK) as the procedure of choice for treating corneal endothelial dysfunction.

And refinements keep on coming. Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) gained favor when surgeons began dissecting donor tissue with a microkeratome and eye banks began providing precut donor tissue.1 “Since 2007, DSAEK has been the standard of care, amounting to about 80 percent of endothelial corneal transplants performed in the United States,” said cornea surgeon Francis W. Price Jr., MD, president of the Price Vision Group in Indianapolis.

Today, Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) is emerging as a contender. Recently published reports have offered information on visual outcomes, graft survival, and endothelial cell loss, among other issues. Is it time for you to adopt DMEK? Here’s a look at the procedure, with some pros and cons to consider.

Overview

DMEK presents surgeons with two primary challenges: stripping the donor graft and then manipulating it, said Donald T. H. Tan, MBBS, director of the Singapore National Eye Centre.

Stripping the graft. The DMEK graft consists only of an isolated endothelium–Descemet membrane layer. (In contrast, DSAEK involves transplantation of the donor endothelium, Descemet membrane [DM], and posterior corneal stroma.)

Although graft loss attributable to tearing of the DM remains a potential concern, said Dr. Tan, the process of “stripping DM off the donor button is now generally solved,” and researchers have described similar techniques that can be used to strip DM successfully. “While other modifications may occur, such as development of specific instruments to aid in stripping, the procedure is generally now possible with a high degree of success,” Dr. Tan added, “and I feel that most eye bank technicians can eventually perform it with appropriate training.”

Manipulating the graft. Handling the stripped DM donor tissue continues to present a challenge, said Dr. Tan. The tissue “almost always scrolls up on itself, with the endothelial layer outward. While this actually makes insertion easier compared with DSAEK—because the scrolled-up tube of DM has a long, thin profile—the main challenges are unrolling it in the anterior chamber, determining which side has the endothelial layer, and actually positioning it centrally without wrinkles.”

All of these maneuvers “have to be performed without touching the DM graft because that will damage endothelial cells,” Dr. Tan said. “Current techniques involve using short blasts of balanced salt solution or air. As in DSAEK, viscoelastic cannot be used, as it may get between the donor and the recipient cornea.”

No More Wrinkles?

How can surgeons solve the problem of the difficult-to-handle DM graft during DMEK? “We have come up with a simple approach,” reported Dr. Tan. Because the DMEK donor graft lacks the stromal component of the DSAEK donor graft, his team has developed a carrier platform that serves as the stromal component. Here’s an overview.

No touch. Dr. Tan’s technique involves a platform, which his team calls the D-Mat. The mat is made of an ultrathin (50 µm), transparent polymer. As its diameter is larger than the DM graft, “one grips the edges of the mat rather than the DM itself,” Dr. Tan said. And because the mat has the correct “tensile strength, elastic memory, and flexibility, it won’t wrinkle up, which means that the DM can’t wrinkle up.”

Not much solution. Dr. Tan’s team also “strips the DM in such a manner so as to prevent it from scrolling up in the first place,” he said. “This is achieved by stripping the DM under very little donor storage solution. A deep chamber of fluid will allow the DM to scroll up, so we use just a shallow level of solution to prevent automatic scrolling.”

Onto the mat. The surgeon slips the mat under the DM, which is lying with the endothelial surface facing up. “The DM will thus attach well to the mat after any excess fluid is wicked off, so that it will neither scroll nor wrinkle up,” Dr. Tan said.

Into the eye. At this point, the mat is coiled up and loaded into the Tan EndoGlide graft inserter (AngioTech). Once the EndoGlide is inserted through the wound, its forceps pulls only the DM into the eye, leaving the mat inside the inserter. “Holding the DM with forceps now helps in ensuring the right orientation of the DM and also helps in positioning, which can be performed by injecting air,” Dr. Tan said. “Keeping the anterior chamber shallow at this point prevents the DM from scrolling.”

Clinical trials are under way, and the D-Mat is still at the prototype stage. In addition, the procedure is still not a simple one and has a “distinct learning curve,” Dr. Tan said. Even so, he added, “we feel this technique gives the surgeon much more control of the DM in the eye and may be one further solution to solving the challenge of DMEK surgery.”

|

Benefits

In successful DMEK surgeries, “The anatomy is restored back to normal, with no evidence of any interface between the donor and recipient tissue,” said David T. Vroman, MD, a cornea specialist with Carolina Cataract & Laser Center in Charleston, S.C., and the medical director for Lifepoint Eye Bank. “And when DMEK works, which is most of the time, you can truly provide superior visual acuity.”

Visual acuity. Indeed, several studies have reported excellent outcomes with DMEK. “Where DMEK really pulls away from DSAEK has to do with visual acuity,” said Dr. Price, who also heads the board of directors of the Cornea Research Foundation of America. “We get better results—by one or two lines—with DMEK, and that makes all the difference.”

In a comparison of DMEK and DSAEK, DMEK provided faster and more complete visual rehabilitation.2 Six months after surgery, 95 percent of the 38 DMEK patients had a BCVA of 20/40 or better, and 50 percent had a BCVA of 20/25 or better. In comparison, 43 percent of the 35 DSAEK patients achieved 20/40 or better, and 6 percent reached 20/25 or better.

And in an evaluation of 136 eyes that underwent DMEK, the mean BCVA was 20/24. “This exceeds the visual acuity results typically reported for DSAEK, which have ranged from 20/34 to 20/66 with a mean follow-up of nine months,” the researchers noted.3

This difference may be explained in part by the finding that DMEK induces fewer corneal surface higher-order aberrations (HOAs) than either DSAEK or PK. In a retrospective analysis of data, both DSAEK and PK patients exhibited increased posterior corneal HOAs even years after surgery. In contrast, the DMEK patients had minimal HOAs.4

Refractive outcomes. DMEK appears to offer better postoperative refractive outcomes than DSAEK, which has been linked to hyperopic shifts ranging from 0.7 D to 1.5 D. In contrast, the one-year study of DMEK found a hyperopic shift of 0.24 D and a reduction of 0.16 D in the negative cylinder; neither of these results was statistically significantly different from the preoperative status.3

Wound integrity. DMEK (like DSAEK) is a small-incision, sutureless, closed procedure. “If you get a suprachoroidal hemorrhage during DMEK,” said Dr. Price, “you close the eye; it’s usually a self-sealing incision. Then you wait a couple of weeks and reassess.”

Postoperatively, the DMEK incision—2.8 mm or smaller—“is not going to rupture,” Dr. Price added. This is in stark contrast to what is seen with PK patients, in whom “even minor trauma to the eye can easily lead to wound rupture,” he said.

|

|

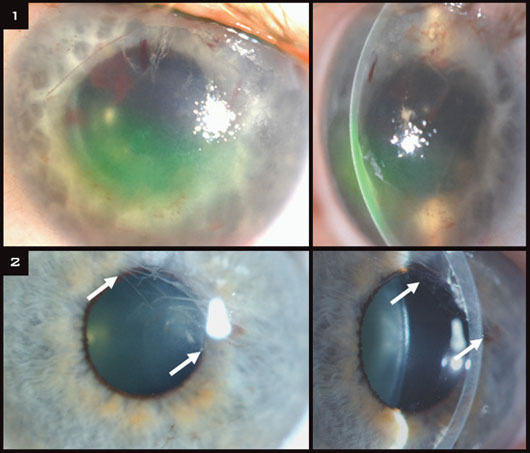

(1) Intraoperative hemorrhage caused by traction on the peripupillary iris stroma just before the injection of air to lift the Descemet graft toward the recipient stroma. (2) In a different patient, paracentral wrinkles (arrows) one year after DMEK caused by air-bubble entrapment behind the iris.

|

Concerns

Endothelial cell loss. As DMEK is a relatively new procedure, data are lacking on long-term endothelial cell survival. Two recent studies provide six-month and one-year data: In one study, DMEK and DSAEK patients showed similar rates of endothelial cell loss at six months—41 and 39 percent, respectively.2 And at one year, Guerra et al. found that the mean cell loss in DMEK patients was 36 percent.3

Graft detachment. As with other EK procedures, DMEK grafts may partially or completely detach, requiring repeated air injections, or rebubbling, to reattach the graft. For instance, Tourtas et al. found that 31 of 38 DMEK eyes (82 percent) showed partial graft dehiscence compared with 7 of 35 DSAEK eyes (20 percent).2

In addition, 8 of the 31 DMEK eyes (26 percent) required more than one air injection to reattach the graft. They noted that additional research and modifications in surgical protocols may lead to a lower rebubbling rate.

“We still don’t fully understand why partial detachments occur,” said Dr. Tan. “Often, on the first day, the donor tissue is fully attached. Of course, there is still a large air bubble in the anterior chamber, which helps in the attachment. But a few days later, when the air bubble disappears, areas of detachment may be seen.” This may be due to “some form of temporary endothelial dysfunction, or else due to endothelial cell damage or loss in those areas,” he added.

According to Dr. Tan, Dr. Price now recommends that “minor peripheral detachments may in fact be left alone, and most of them will automatically reattach with time. As a result, Dr. Price’s rebubbling rate has now dropped. I feel that we have probably been rebubbling minor cases of detachment unnecessarily, so rates will probably drop significantly if this is true. Certainly, if we are able to reduce endothelial damage with the actual DMEK operation, we should see a reduction in these rates.”

Graft rejection. In 136 consecutive cases of DMEK, 11 grafts failed, and episodes of immunologic rejection were documented in seven eyes during the first year of follow-up. However, most occurred at a center that tapered steroids vary early.3

More recently, Dr. Price’s center conducted a head-to-head comparison of DMEK, DSAEK, and PK performed for the same indications and with the same steroid regimen. In this study, the risk of rejection was lowest in the DMEK group. Only one of 141 DMEK grafts (0.7 percent) experienced a rejection episode, versus 54 of 598 DSAEK grafts (9 percent) and five of 30 PK grafts (17 percent).5

Dr. Price described these latest findings as “startling.” He added, “The current thinking has been that the endothelium had a lot of antigenic load and the stroma had less; our findings imply that the stroma has a significant role in stimulating rejection.” Given DMEK’s newness as a procedure, additional studies to document the rate of rejection with DMEK are needed.

A Note on Patient Selection

“One should note that DMEK is still generally only performed in standard, noncomplex cases—that is, mostly for Fuchs endothelial dystrophies or uncomplicated cases of pseudophakic bullous keratopathy,” Dr. Tan said. “In complicated cases, such as previously vitrectomized eyes, aphakia, previously failed grafts, or glaucoma cases with setons or drainage blebs, DMEK is currently still contraindicated and DSAEK remains the procedure of choice.” With regard to glaucoma drainage devices, “You can bang up against the tube,” said Dr. Price.

In addition, DMEK isn’t recommended for patients with anterior chamber intraocular lenses or peripheral anterior synechiae and iris abnormalities, including aniridia.

But apart from these limitations, DMEK is appropriate for patients who have problems with reading or driving because of glare and fluctuating vision. “Patients who have high demands regarding their work or activities are good candidates,” said Dr. Vroman. For instance, he has performed the procedure on several surgeons. “I also had a pilot who often flies at night and had to have 20/20 vision.”

Slow Route to Acceptance

Overall, DMEK appears to be gaining traction more slowly than DSAEK did. “It’s still not widely accepted,” Dr. Vroman acknowledged. Dr. Tan noted, “There are many experienced DSAEK surgeons who have now embarked on performing DMEK, but we don’t see many results or presentations at this time.”

What’s behind the slow route to acceptance? “I don’t think it’s an issue of outcomes,” Dr. Vroman said. “We know that one- and two-year visual acuity results are generally better than those seen with DSAEK.” And although long-term endothelial cell counts are still unknown, “I don’t think that’s the issue,” he said.

Instead, DMEK’s learning curve appears to be at the heart of the matter. As things now stand, DSAEK is a known quantity. In contrast, Dr. Vroman said, “DMEK surgery is more complex and delicate, and the possibility of losing tissue is a big concern.”

Thus, DMEK remains a procedure in transition. However, as cornea researchers continue to refine their techniques, things may change. “At the end of the day, if surgery techniques are improved to the level where most cornea surgeons can safely and consistently perform this procedure, DMEK may ultimately become a mainstream procedure,” said Dr. Tan. And as Dr. Price noted, “As good as DMEK is, I’m fairly certain that the next two years will make a significant difference. As more surgeons join in, the overall level of quality will go up.”

Yet Another Alternative

Another option—ultrathin DSAEK—may even render the DMEK versus DSAEK debate moot.

“The main reason to perform DMEK is that it has the potential to provide better BCVA than DSAEK, as there is not the additional stroma-to-stroma interface that occurs in DSAEK,” said Dr. Tan. “Having said that, ultrathin DSAEK—in which the donor graft thickness may be anywhere between 50 and 100 µm—is now beginning to show visual results that may match DMEK. So, the question is whether ultrathin DSAEK will become mainstream.”

It has a big advantage as well, he added. On the one hand, ultrathin DSAEK is “a bit more challenging to perform than normal DSAEK—the ultrathin donor is more difficult to manipulate, as it can wrinkle easily—and may also result in higher endothelial cell damage.” However, “it is still easier to perform than current DMEK surgery.”

Ultrathin DSAEK does have a significant downside, though, said Dr. Tan. “The main problem is being able to consistently achieve an ultrathin donor, which may result in a higher rate of donor tissue loss.”

“Nevertheless, if thin grafts provide better vision, DMEK is the thinnest option,” said Dr. Price. “Microkeratomes always induce some irregularities in the donor tissue because they do not create a perfectly even cut. Any interface or thickness irregularities can decrease BCVA and/or increase HOAs, no matter what the procedure.”

___________________________

1 Anshu A et al. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57(3):236-252.

2 Tourtas T et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(6):1082-1090.

3 Guerra FP et al. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2368-2373.

4 Rudolph M et al. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(3):528-535.

5 Anshu A et al. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(3);536-540.

___________________________

Drs. Price and Vroman have no related financial interests. Dr. Tan has a financial interest in the Tan Endoglide device.