By Jordan Martin, Albert S. Khouri, MD, and Vishal Jain, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from January 2009 and may contain outdated material.

What started out as just another night of watching television turned out to be anything but ordinary for Bob Kaiser,* a 39-year-old comic book store owner. At around 1 o’clock in the morning, while snacking on popcorn and watching late-night television with his wife, Mr. Kaiser suddenly felt a choking sensation and found it difficult to swallow his own saliva. As Mrs. Kaiser attempted to aid her husband, she was quick to notice that his right eyelid was now drooping. By the time Mr. Kaiser arrived in the ER, he also complained of a difficult-to-characterize sensation on the left side of his body in his arm, trunk and leg.

We Get a Look

When we saw Mr. Kaiser in the emergency department, he was resting in his gurney. He occasionally was spitting out his saliva because of dysphagia. Indeed, attempting to swallow his saliva lead to violent coughing. He had never experienced any similar symptoms previously and denied ocular pain, double vision or a change in visual acuity. Mr. Kaiser suffered from hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea but was not compliant with therapy for either condition. He had a body mass index of 45.

On physical examination, there was a 2-mm ptosis of the right upper eyelid, and upside-down ptosis of the right lower eyelid (Fig. 1). Levator function and extraocular muscle movements were preserved. His pupils appeared equal in the brightly lit ER. However, in a dimly lit room, we noticed that the right pupil was 2 mm smaller than the left pupil. No nystagmus was present. Visual acuity, color vision and biomicroscopic eye examination were normal. There were no signs of altered sweating in the face.

Neurologically, Mr. Kaiser’s cranial nerve examination revealed a deviation of the uvula to the left side and a diminished gag reflex, consistent with involvement of the right cranial nerves IX and X. Although motor strength and tone were normal in his arms and legs, sensation to pain and temperature was decreased in the left leg, left side of trunk, and left arm up to his neck. Facial sensation was normal.

Mr. Kaiser had a wide-based gait and had difficulty maintaining balance well.

Differential Diagnosis

The findings of unilateral upper eyelid ptosis, lower eyelid upside-down ptosis and miosis are consistent with Horner’s syndrome. Causes of this syndrome are typically divided into central, pre- and postganglionic (superior cervical ganglion). Central lesions include brainstem tumors or infarcts. Preganglionic causes include Pancoast’s syndrome of lung tumor, carotid dissection or neck trauma. Postganglionic etiologies include nasopharyngeal tumors, high internal carotid dissection and vascular headaches, as well as cavernous sinus pathology.

The combination of Horner’s syndrome, cranial nerve paresis causing dysphagia and contralateral sensory deficit in our patient pointed toward a central etiology involving the brainstem. Neoplasms or vascular causes (infarct, thrombosis, dissection or aneurysms) could potentially explain Mr. Kaiser’s symptoms and signs.

|

|

WE GET A LOOK. We noted right upper lid ptosis and right lower lid upside-down ptosis. When we dimmed the lights, his right pupil was smaller than his left.

|

Neuroimaging

While Mr. Kaiser was in the ER, a CT scan of his head was obtained to look for evidence of infarct or mass lesions. The scan was unremarkable and did not elucidate the cause of his symptoms.

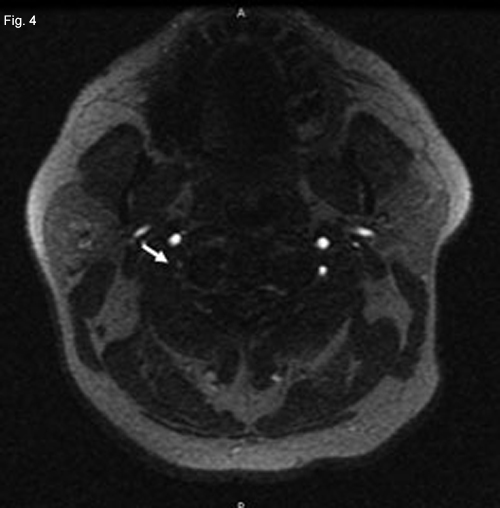

A posterior circulation infarct remained a possibility, and an MRI of the brain and MR angiography (MRA) of neck vessels were obtained. The MRI revealed evidence of a recent infarct in the right medulla (Fig. 2). The MRA showed nonvisualization of the mid- to upper-right vertebral artery consistent with thrombosis, severe stenosis or dissection (Figs. 3 and 4). With this new information, a diagnosis of lateral medullary syndrome was made.

|

|

|

NEUROIMAGING. Since a posterior circulation infarct seemed possible, we obtained an MRI of the brain and MRA of the neck vessels. Restricted diffusion (white arrow) in the right half of the medulla seemed consistent with a recent infarct. Decreased visualization of the distal right vertebral artery (white oval) compared with the left vertebral artery (white arrow) in an MRA reconstruction of neck vessels. Marked tapering of the distal right vertebral artery (white arrow) on axial MRA image.

|

Discussion

Lateral medullary syndrome, or Wallenberg’s syndrome, is a rare condition that results from an embolic occlusion or thrombosis of the arterial blood supply to the medulla, leading to ischemia.1 The ipsilateral vertebral artery is implicated in the majority of cases, although the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) also can be responsible.1 This syndrome can involve the tracts in the lateral spinal cord and the nuclei of cranial nerves within the medulla.

A variety of symptoms may be seen, depending on which nuclei and tracts are involved. Such signs and symptoms include numbness of the ipsilateral face and contralateral limbs, diminished pain and temperature sensation of contralateral body, diplopia, nystagmus, vertigo, ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, paralysis of ipsilateral vocal cord, weakness of ipsilateral palate and ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome.1,2 Partial syndromes can be seen with occlusions of the penetrating branches of either the vertebral artery or the PICA.1

In our patient, the sympathetic and spinothalamic tracts, as well as cranial nerves IX and X, were involved. This explained his Horner’s syndrome (ptosis, upside-down ptosis and miosis from sympathetic involvement), loss of pain and temperature (spinothalamic tract) and inability to swallow (nucleus ambiguus).

There are numerous etiologies that can cause lateral medullary syndrome secondary to posterior circulation ischemia. The most common condition is vertebral artery atherosclerosis.2 As with atherosclerosis in other blood vessels, there is a strong association with smoking, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia.2

Vertebral artery occlusion also can be the result of emboli. These emboli can have many origins, including cardiac. However, in one study 24 to 50 percent of emboli came from a plaque that originated in the vertebral artery itself.3

An aneurysm is another condition that can lead to medullary ischemia or can compress the medulla. They are not common in the posterior circulation, but when they occur, the most common site is at the basilar artery apex.2 Most aneurysms of the posterior circulation can be detected by either MRI or MRA. This was not seen in our patient.

Dissections of the posterior circulation also can result in brain stem ischemia, with the extracranial vertebral artery usually implicated.2 It has been recognized that minor trauma can result in spontaneous dissection; therefore, a history of major trauma is not necessary.2 Signs and symptoms from the ischemia may develop immediately or may be delayed hours to days after the trauma, further decreasing the chance of a patient recalling a minor trauma.2

Another interesting, though less common, cause of posterior circulation ischemia is compression of the vertebral artery by osteophytes. The vertebral artery runs in the transverse foramina, which makes it susceptible to projections of osteophytes from adjacent vertebral joints.2 A majority of patients with spondylosis also have coexisting atherosclerosis, further adding to the susceptibility of the vertebral artery to compression by osteophytes.2 There also have been reports of vertebral artery inflammation due to temporal arteritis leading to posterior circulation ischemia.2

After reviewing the possible etiologies for our patient’s symptoms, it appears the most likely cause was atherosclerosis. Not only is this the most common condition leading to vertebral artery occlusion, but our patient had a history of uncontrolled hypertension and morbid obesity. However, dissection from inconspicuous trauma should be kept in mind as a cause in younger individuals.

Treatment

Treatment for posterior circulation ischemia is not well-defined, as there have not been studies that definitively establish the advantages and disadvantages of a given therapy. In many patients, anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies are used. The benefits of medical and surgical treatment regimens are inferred from carotid studies.3 Thrombolysis and embolectomy may provide benefit if treatment is provided within a few hours of symptom onset; however, larger studies are needed.4 If the etiology for the ischemia is a vertebral artery aneurysm, surgical clipping can be utilized, but more often coils and balloon stenting have been employed.5

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Fauci, A. S. et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 17th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008).

2 Barnett, H. J. M. et al. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management, 2nd ed. (New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1992).

3 Spelle, L. et al. Neuroimag Clin N Am 2006;16:413–451.

4 Lutsep, H. L. et al. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;17:55–57.

5 Dabus, G. et al. Neuroimag Clin N Am 2007;17:381–392.

___________________________

Mr. Martin is a fourth-year medical student at Drexel University, Philadelphia. Dr. Jain is a hospitalist in the Internal Medicine Department and Dr. Khouri is a resident at Saint Peter’s University Hospital–Drexel University, New Brunswick, N.J.