By Brett D. Gerwin, MD, and Lanning B. Kline, MD

Edited By Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from February 2007 and may contain outdated material.

Friday night was another football game for Matt Williams,* a 17-year-old who was proud to be playing for his high school. The ball was handed off to Mr. Williams just as a player from the opposing team ran into him, knocking him unconscious. He gradually regained consciousness as the officials and his coach ran over. He was taken to a local emergency room where he was evaluated. A CT scan of his head was normal and he was discharged that evening.

Determined to Play Football

Throughout the following week, Mr. Williams went about his usual daily activities. His family and friends thought he was back to normal—but he knew otherwise.

He was suffering from headaches, but he kept this to himself lest he be sidelined for the next game. After telling his coach and parents that he was ready to play, he was back on the field the following Friday night. He played part of the game before collapsing on the side of the field.

He Returns to the ER

Mr. Williams was rushed to the university emergency department where he was evaluated. When questioned, Mr. Williams could not recall what had happened.

He denied any prior medical problems, medication or drug use, allergies or prior surgeries.

A CT scan of the head revealed a subdural hematoma on the left with a large amount of cerebral edema and midline shift.

He was admitted to the neurosurgical intensive care unit and, because he complained of diplopia, we were asked to look at him.

We Get a Look

On examination, Mr. Williams was lethargic but awake and denied that there had been any change in his visual acuity. He was able to read J1 on the near vision test card with each eye.

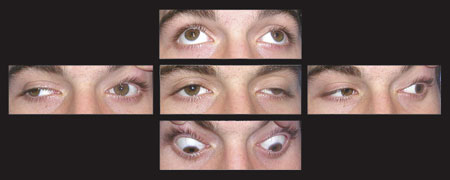

He had no anisocoria and no relative afferent papillary defect. His color vision was tested with the Ishihara color plates, and it was normal in both eyes. Our initial confrontation visual fields test demonstrated a right homonymous hemianopia. Mr. Williams’ ocular motility was abnormal with limited elevation, adduction and depression of the left eye (Fig. 1).

He had ptosis of the left eye. Otherwise his examination was normal, including no anterior and posterior segment abnormalities.

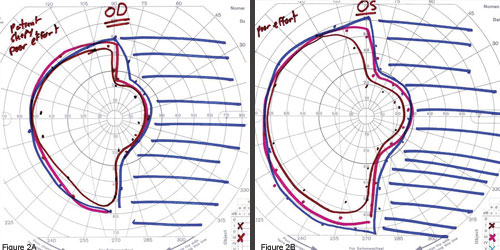

After Mr. Williams was transferred out of the ICU, formal visual field testing demonstrated a right homonymous hemianopia with macular sparing (Figs. 2A and 2B).

An MRI of his brain showed a left occipital lobe abnormality.

|

|

Limited Motility. (Fig. 1) We saw Mr. Williams one week after he had been knocked unconscious during a football game. His motility was abnormal, with limited elevation, adduction and depression of the left eye.

|

Diagnosis

Our patient presented with a right homonymous hemianopia with macular sparing and a partial left third nerve palsy. This occurred in the setting of a left subdural hematoma with substantial cerebral edema and midline shift of the brain.

|

|

Further Testing. (Figs. 2A and 2B) Formal visual field testing confirmed that Mr. Williams had a right homonymous hemianopia with wide macular sparing.

|

Treatment

Mr. Williams was followed in the intensive care unit and treated with intravenous hyperosmotic agents and corticosteroids to reduce his cerebral edema. Follow-up scans revealed significant improvement in his brain edema and midline shift so a decision was made not to evacuate the hematoma.

At a clinic visit six weeks after injury, he demonstrated normal eye movements, lid position and pupillary responses. His visual fields had markedly improved, with only a partial right inferior homonymous quadrantanopia remaining.

|

|

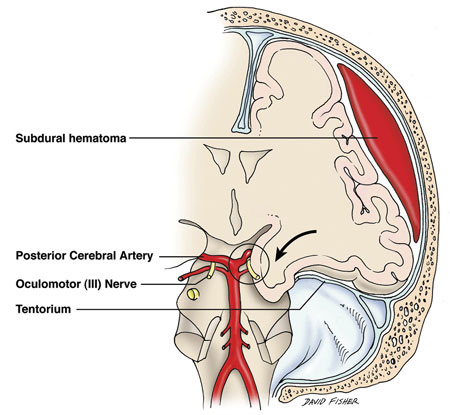

Figure 3. Transtentorial herniation from subdural hematoma with compression (circled area) of ipsilateral third nerve and posterior cerebral artery.

|

Discussion

The mechanism by which this constellation of signs and symptoms may occur together is transtentorial herniation of the temporal lobe. Herniation in the setting of increased intracranial pressure compresses the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) as well as the underlying third nerve near its exit from the midbrain (Fig. 3).1The PCA is compressed against the tentorium at any point along the tentorial edge and leads to occipital lobe ischemia.2 At times, the contralateral PCA can also be compressed, leading to bilateral occipital lobe involvement.3

Because the left PCA and left occipital lobe were involved, our patient developed a right homonymous hemianopia. He was relatively unaware of his field defect, possibly due to sparing of the occipital tip by its dual blood supply from both the middle and posterior cerebral arteries.

Third nerve palsy is a well-described clinical finding with transtentorial herniation, often heralded by pupillary dilation.4 Mechanisms include direct compression by the temporal lobe beneath the tentorial edge, or compression by the proximal segment of the PCA.1,4 In our patient, the third nerve palsy was incomplete with no documented anisocoria. Other reported ocular motor signs of transtentorial herniation include unilateral or bilateral ptosis, internuclear ophthalmoplegia and vertical gaze paresis.5

This case is particularly interesting for four reasons:

- the patient had a normal cranial CT scan one week prior to admission,

- the patient’s second CT scan revealed cerebral edema and midline shift due to a subdural hematoma,

- the patient presented with a macular-sparing homonymous hemianopia and a pupil-sparing third nerve palsy, and

- the patient survived without the need for evacuation of the hematoma.

This case illustrates that subdural hemorrhage may lead to ipsilateral third nerve palsy and contralateral homonymous hemianopia through the mechanism of transtentorial herniation.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Walsh, F. B. and W. F. Hoyt. Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, vol. 3, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: Williams & Williams Co., 1969), pp. 2403–2413.

2 Sato, M. et al. Neurosurgery 1986;3:300–305.

3 Soza, M. et al. Can J Neurol Sci 1987;14:153–155.

4 Glaser, J. S. Neuro-Ophthalmology, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999), pp. 419–420.

5 Keane, J. R. Arch Neurol 1986;43:806–807.

___________________________

Dr. Gerwin is a third-year resident, and Dr. Kline is professor and chairman of ophthalmology. Both are at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.