Download PDF

Volunteer ophthalmologists are ramping up the fight against eye disease by building capacity in communities around the world. Here’s how you can help.

Volunteering abroad is undergoing a sea change. Gone are the days of simply flying overseas to an under-resourced community, performing hundreds of cataract surgeries, and returning home to your practice. Most communities now have their own health systems in place with local physicians who can perform procedures at a lower cost than in the past.

Rethinking the Rationale

Instead of “delivering care,” the buzzword in medical volunteerism is now “building capacity.”

Magnify your impact. “Given the cataract backlog in the world today, we are more than 100 years from eradicating this cause of blindness if we simply rely on delivery of care,” said Jeff H. Pettey, MD, at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “Yes, performing cataract surgeries will impact individuals, but it pales in comparison to the overall impact you’ll have if you build capacity in an individual, a practice, and a country.”

Build local partnerships. How is this done? By partnering with individuals and groups to improve education and training. By procuring equipment and connecting communities to local resources. By bringing local physicians to international meetings and uniting them with their ophthalmic societies. “It’s about substituting single-episode surgical care with impact that functions 365 days a year,” said Dr. Pettey. “We as volunteers transfer our skills to a community and empower a population because it’s the members of that community who are best able to care for one another.”

And the more boots on the ground the better. Here’s how you can play a role in the leading edge of global ophthalmology.

Why They Do It

Volunteering is a uniquely individual experience, as each community has distinct needs with its own rewards and challenges. At the same time, each volunteer brings his or her own motivations.

Marc Safran, MD, who practices in Liverpool, N.Y., has volunteered in Bolivia, Ecuador, India, and Vietnam. Doing work overseas allows him to reconnect with the core of why he originally went into medicine. “It’s a throwback to providing medical care to needy people in a free and unencumbered way,” said Dr. Safran, “without electronic health records, MIPS, MACRA, and all of the bureaucratic hassles we now face at home.”

For Mitchell V. Brinks, MD, MPH, the motivation to volunteer overseas in areas like Cambodia, Guatemala, and Myanmar stems from the power of human connection. “It’s a pretty special feeling to know you have friends and a sense of home in another part of the world,” said Dr. Brinks, at Oregon Health & Science University’s Casey Eye Institute in Portland. “Cataract surgery, for example, can open the door to do so much good in so little time. And to have that access to the inside of a community? That’s pretty rare. But we as ophthalmologists have the key—it’s sitting there right in our hands.”

|

|

STRABISMUS. Dr. Safran, shown with a young boy who had strabismus surgery that was provided via Healing the Children in Guayaquil, Ecuador.

|

Become a Better Clinician

Volunteering might mean different things to different ophthalmologists, but all agree on one thing: Whether you are a resident, a young ophthalmologist new to practice, or a seasoned vet, the skills you learn doing mission work will have a significant impact on your practice at home.

Sharpen your skills. “There might not be a better way to hone your skills as an ophthalmologist,” said Dr. Pettey. “You’ll be faced with the most complicated cases and forced to make important decisions in incredibly difficult environments. Afterwards, little will faze you. You return more focused and more capable of making difficult decisions on the fly. When done right, you return a better surgeon.”

You’ll also see the natural progression of diseases in a way that’s just not part of most ophthalmologists’ day-to-day experience in the United States. During his travels, Dr. Safran has witnessed child after child with advanced strabismus, which could have been easily corrected if eyeglasses were available. “Seeing the natural path of uncorrected disease gives you a genuine appreciation of its true nature and severity,” he said. “Whether it’s amblyopia, congenital cataract, or ptosis, I’ve gained a better appreciation for biology in a way that’s not possible in the normal U.S. clinic, where we have more early interventions [available].”

Deepen connections with patients. Not only can volunteering abroad make you a better surgeon, but it also will teach you how to build better physician-patient relationships. “By having the opportunity to work with people from different cultures and backgrounds, I’m building a skill set that translates to a lot of different scenarios domestically,” said resident Travis Redd, MD, MPH, at the Casey Eye Institute.

Andreas K. Lauer, MD, also at the Casey Eye Institute, agreed. “In my experience, it’s been really helpful to learn more about other cultures firsthand so that when I return home, I can interact more meaningfully with patients from diverse backgrounds. If I can tell a patient, ‘Hey, I recently visited your country,’ there’s automatically a better connection.”

Gain greater perspective. In addition to giving you a broader and deeper perspective on another culture, working abroad can also give you a new perspective on your own practice. “Volunteering gives you a window like no other into how commercialized and money-oriented medicine has become here in the United States,” said Dr. Brinks. “Many times, we as physicians buy into the earnings and the patient volume as our metrics of success. We can take it too seriously. Getting out of the clinic and setting foot in another world can help you build another model of professional satisfaction. It can make ophthalmology a truly enjoyable, long-term endeavor.”

For Dr. Redd, his mission work as a resident has made him rethink the role of public health in the practice of ophthalmology. “Going overseas to places like Uganda and Ethiopia reminds me to think about medicine in a different way when I return home. It’s more than just, how am I going to treat someone? It’s, how are my patients getting to the exam room? What hoops do they have to jump through? How can I better recruit my patients and better serve my local community?”

|

|

BUILDING CAPACITY. Today’s No. 1 goal is to help build programs that will continue long after the volunteer returns home. Friendships— as the one between Dr. Brinks (left) and Benjamin D. Siatu’u, MD, who practices in Pago Pago, American Samoa—are a bonus.

|

Getting Started

There are several ways to approach volunteering abroad, depending on your career stage.

Residents. For ophthalmologists still in training, many U.S. residency programs have integrated overseas experiences into their educational program. And some of them will help subsidize a resident’s travel expenses and other costs. For example, the International Ophthalmology Program at the Casey Eye Institute allows ophthalmology residents to travel internationally to areas like Fiji to learn low-cost alternative surgical skills, such as manual small-incision cataract surgery, for treating patients in underserved communities.

Fellows. A small but growing number of institutions around the United States have also created global ophthalmology fellowships to help young ophthalmologists put their training at home into practice abroad. These include the following:

- Dean McGee Eye Institute’s Global Eye Care Fellowship (University of Oklahoma)

- Emory Eye Center’s Global Ophthalmology Fellowship (Emory University)

- Moran Eye Center’s Moran International Ophthalmology Fellowship (University of Utah)

- Truhlsen Eye Institute’s Prevention of Global Blindness Fellowship (University of Nebraska)

- Wills Eye Center for Academic Global Ophthalmology Fellowship (Wills Eye Hospital)

Midcareer and older physicians. More established ophthalmologists may want to consider volunteering through a charitable or nonprofit organization. Groups like Orbis International, the Seva Foundation, and the Himalayan Cataract Project, for example, serve close to 100 countries and train thousands of medical professionals a year in how to build self-sustaining programs for preserving and restoring vision. For such a trip, most ophthalmologists can expect to take a hit on the income they’d normally bring in from their own practices, but some of these organizations might be able to offset a portion of the costs, including travel and lodging.

|

|

TEAM EFFORT. Patients, their family members, and members of the team from Healing the Children. The group of 5 ophthalmologists and 20 staff performed 125 general strabismus cases during a week-long mission in Guayaquil, Ecuador.

|

Developing a Plan

Regardless of the route you take to get involved, prospective volunteers will want to heed the following expert advice when exploring their opportunities.

Start at home. After a decade of local volunteering, Linda M. Lawrence, MD, who practices in Salina, Kansas, began collaborating with more than 30 nonprofit organizations everywhere from Nigeria to Vietnam. Her advice for prospective global ophthalmologists? Don’t just jump on a plane. Start by doing work around your local community.

She said, “When a new volunteer asks me how they can get involved in international work, I ask them, ‘What are you doing at home?’ Home is your training ground. Home is where you learn about people and different health care systems. It’s where you learn how to network and really how to volunteer.”

EyeCare America. You can do mission work without ever leaving your office, thanks to the Academy’s EyeCare America program. The program helps medically underserved seniors and those who are at increased risk for glaucoma receive eye care through dedicated volunteer ophthalmologists. Once an ophthalmologist enrolls as a volunteer, eligible patients are matched online to the nearest volunteer by zip code.

Find a mentor. Dr. Pettey’s experience echoes that of Dr. Lawrence. Before taking his experience overseas, he started volunteering locally in a homeless clinic in Salt Lake City. And he is adamant about the importance of mentors. Under the guidance of Drs. Randy Olson, Alan Crandall, and Geoff Tabin at the Moran Eye Center, he learned how to translate the skills he was developing at home into the ability to provide high-quality care abroad.

“Good mentors really are the doorway to involvement,” Dr. Pettey said. “As a young ophthalmologist, you don’t have a clinical skill set that translates to the developing world. The cataracts you’ll encounter, for example, are the most difficult cases you’ve seen. It takes mentors who can build that clinical capacity in you before you can really get to work in a different country.”

Even for the most seasoned physician, a good mentor can prevent you from becoming a burden, added Dr. Brinks. “You’re not sleeping well, you have jet lag, you might have a bug, everything is difficult,” he said. “Unless you have someone alongside you who’s gone through it before, you’ll have to relearn their same mistakes on patients who are in dire need. So even for the smartest ophthalmologist out there who has the best of intentions, there’s just too much to learn on the ground to think you can do it by yourself the first try.”

Go with a group that has experience. Your first impressions of your mission site will be vital, so find an experienced organization to join. “Inspiration is your fuel when you’re volunteering abroad,” said Dr. Brinks. “And it’s delicate. You don’t want a traumatic experience to destroy it. So, research the location and go with a group that reflects your own values, because once you go overseas, the regulations and standards of care that you are accustomed to are all gone. The only things you have to guide you are the values and principles of the people you surround yourself with.”

Consider long-term impact. Finally, be sure the organization has a plan for long-term follow-up care, Dr. Redd added. “Many new volunteers think they’ll just pop into an outreach camp, work for a few days, and then return home. That might sound appealing, but you can do more harm than good in the long run if the organization has no plan for follow-up care and has no foundation built up for referral networks to help patients after you leave.” You have a duty to these patients to volunteer with a responsible organization, he said.

Before You Go

Once the path is clear and you’ve decided on your journey, you’ll want to make sure you follow a standard to-do list:

- Get your passport ready. The minute you decide you are going somewhere, check the official country website and figure out what you need (e.g., passport and visa) to enter the country. Plan ahead; the materials can take months to acquire.

- Make sure you’re licensed. You’ll head out overseas with the best of intentions. But if you aren’t legally approved by the host country’s government to perform surgery in your host country, you’ll be heading back home sooner than expected.

- Get your vaccines. This is essential. Some countries may even require proof of immunization prior to entry.

- Purchase evacuation insurance. You don’t want to become acutely ill and stranded in a foreign country that lacks proper resources. In addition to purchasing health insurance when traveling abroad, you should obtain evacuation insurance. This service will provide a jet or helicopter to extricate you from the direst of circumstances.

- Register with the appropriate U.S. consulate. You shouldn’t expect any danger when you are working overseas, but you’ll want to make sure the U.S. State Department knows where you are in case of catastrophe, natural disaster, or political unrest.

- Learn the language. Doing your homework about the local language and cultural makeup will be tremendously helpful down the road. You don’t need to be fluent, but learning simple terms like “thank you” and “good evening” will ingratiate you with hosts and patients.

|

On the Ground

No matter how long you prepare for your work overseas, there are certain things that only experience can teach when you touch down on the ground.

Don’t be the hero. “As a resident or new volunteer in a foreign country, keep in mind that you are first a guest,” said Dr. Lauer. “So be respectful of the host because the host has a lot of responsibility. There’s a cost to them to ensure that the visit achieves the aim. If you go over there thinking that you’re going to run the show, you won’t be welcomed back.”

It’s also important to remember that your surgical skills or station in life should never dictate how you interact with the people you meet on the ground. “Fifteen years ago, physicians in the developing world didn’t have great access to the internet,” Dr. Safran said. “Times have changed, and now an ophthalmologist from the furthest reaches of the globe might very likely be a better surgeon than you. So, treat every person you meet—physicians, nurses, patients, community members—as a fellow human citizen.”

Don’t undercut the local economy. “This is something very important that I’ve learned from decades of volunteering abroad,” said Dr. Lawrence. “Where I work in Peru, for example, I used to bring donated [glasses] frames to a local school. But a mother of one of the students is an optician in the community. Why would I want to compete with her and take away her livelihood? In the end, you want to transfer your skills and promote the local economy and infrastructure.”

Understand your limits. Perhaps the most important caveat is to set realistic expectations of yourself, the experts said. For a resident, this might mean that you simply go as a student rather than a practitioner. But even the most experienced ophthalmologist will still want to be cognizant of his or her comfort zone. Clinics overseas might be saving up the most difficult cases for someone like you. But if it involves something that youwouldn’t normally do or involves compromising on your own safety or the safety of your patients, you should know when to say “no” and defer to someone else.

“Most of the patients you’ll see are going to be blind, and they will need a lot of care,” said Dr. Brinks. Arriving at your destination “with an undefined desire to help isn’t a sophisticated strategy. People try to work themselves to death. They’ll do things they’re not ready to do, and then there’s nobody to help fix the problem afterwards. So be safe, be calm, and be humble.”

|

|

ZIKA OUTREACH. Dr. Lawrence with a mother and infant in Brazil, both of whom were affected by the Zika virus.

|

An Unmet Need

According to the World Health Organization, almost 90% of the world’s visually impaired live in low-income countries. And in these areas, treatable cataracts are the leading cause of blindness.1 It’s therefore no surprise that mission work to provide cataract surgery is the leading intervention for ophthalmologists. But there are also millions of others suffering from other diseases, such as glaucoma, who require ophthalmology’s attention. And this is where new recruits play a vital role.

“Manual small-incision cataract surgery is definitely an amazing type of intervention to prevent blindness,” said Dr. Lauer. “It has the ‘wow’ factor. But as we get more sophisticated about doing international missions, building capacity, and investing in public health, we need to expand our focus and find new volunteers to tackle these other conditions. It’s going to be a challenge, but if we can help these patients collectively, we really will be making the world a better place.”

___________________________

1 World Health Organization. Global Data on Visual Impairments 2010. Accessed Oct. 25, 2017.

The Academy’s GO Guide

“Familiarizing yourself with global ophthalmology is one of the best ways to get started,” said Dr. Pettey. “And to really prep my residents, I send them to the Academy’s Global Ophthalmology (GO) Guide.”

The guide provides members-in-training with a listing of fellowships and observerships available as well as online CME courses for all physicians who want to work overseas. Topics include the following:

- “Starting in Global Ophthalmology: Mentorship, Funding, and the Work-Home Balance”

- “Assessing Outcomes in Global Health Programs”

- “So You Want to Work Overseas?”

You can use the GO Guide to find region-based treatment and management information on a variety of disease topics; multimedia clips pertaining to global ophthalmology; and an Academy pamphlet, “Before You Go,” in which veteran physicians discuss how to make lasting changes around the world.

Prospective volunteers will also want to check out the Academy’s “Advisory Opinion on Ethical Issues in Global Ophthalmology.” It covers the challenges involved in international ophthalmic care, including how ophthalmologists can maintain professionalism and high clinical standards while practicing abroad.

|

Meet the Experts

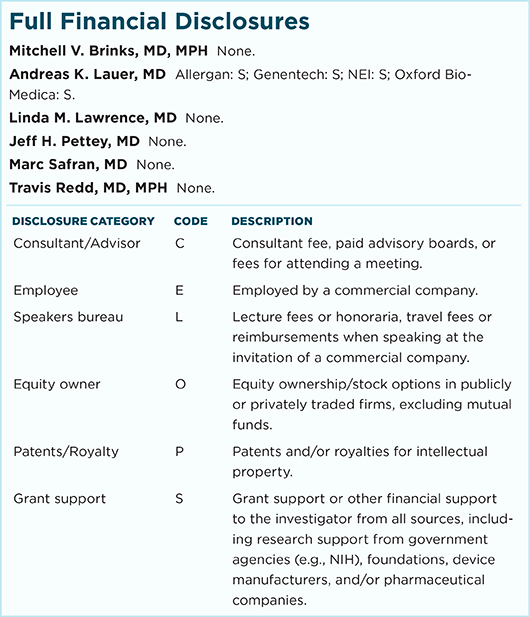

Mitchell V. Brinks, MD, MPH Assistant professor of ophthalmology and codirector of the International Ophthalmology Program at Oregon Health & Science University’s Casey Eye Institute in Portland. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Andreas K. Lauer, MD Professor of ophthalmology, vice-chair for education, and chief of the Retina-Vitreous Division at Oregon Health & Science University’s Casey Eye Institute. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Linda M. Lawrence, MD In private practice in Salina, Kansas. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Jeff H. Pettey, MD Associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, residency program director, and medical director of global outreach at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Marc Safran, MD In practice at the Clay Eye Center in Liverpool, N.Y., and associate faculty professor at Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse, N.Y. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Travis Redd, MD, MPH Second-year ophthalmology resident at Oregon Health & Science University’s Casey Eye Institute. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

|