Download PDF

Vision rehabilitation has traditionally been viewed as an intervention driven by the failure of ophthalmic care, and that perspective needs to change, according to low vision experts. An aging population, new technologies, and a growing body of evidence-based research have significantly broadened the scope of vision rehabilitation, according to Mary Lou Jackson, MD, at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. It’s time for ophthalmologists to reframe the role of rehab as part of a continuum of good eye care.1

Your Evolving Role

“Ophthalmologists need to recognize that identifying and responding to their patients’ vision loss by offering information about rehabilitation is the current standard of care, just as neurologists recommend stroke rehabilitation and cardiologists offer cardiac rehabilitation,” said Dr. Jackson.

“Patients may not find, or even be aware of, vision rehabilitation services without guidance from their ophthalmologists,” said Lylas G. Mogk, MD, at the Center for Vision Rehabilitation & Research in Grosse Pointe, Mich.

Start early. “Part of that responsibility is advising patients early in their disease process,” said Dr. Mogk, “because even mild vision loss can be debilitating and anxiety-provoking.” The Academy’s Vision Rehabilitation: Preferred Practice Pattern (PPP) recommends referral when corrected acuity is less than 20/40 in the better eye or when there is impaired contrast sensitivity, visual field loss, or a scotoma.2 When corrected acuity is 20/50 or worse, patients have two times the risk of falling, four or more times the risk of hip fracture, and three times the risk of depression; they are admitted to nursing homes an average of three years earlier than their peers.3-5

Because many conditions that cause low vision are progressive, ophthalmologists and occupational therapists need to maintain a close relationship, referring patients back and forth if visual function changes.2

|

Practical Ramifications

|

|

|

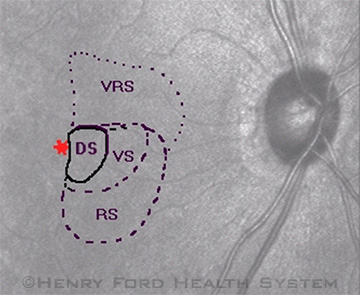

Scanning laser ophthalmoscopy from a patient who complained bitterly of difficulty reading after a cerebrovascular accident that had been deemed resolved by his previous physicians. He had a very small scotoma, affecting both eyes, immediately to the right of central fixation. Thus, when reading left to right, he read into the scotoma, slowing him down tremendously. Although this effect was very troubling for the patient, it would be considered a mild residual deficit. KEY: Red asterisk is the fixation point, in this case the fovea; DS, dense scotoma; RS, relative scotoma, which is present only in dark conditions; VRS, variable relative scotoma; VS, variable scotoma.

|

Comprehensive Rehab

Comprehensive vision rehabilitation doesn’t rely on a single device or training technique. It is a multidisciplinary approach that addresses the whole person, examining the broader impact of vision loss on the patient. This type of rehabilitation takes into account five aspects of the patient’s life: reading, activities of daily living, safety, participation in the community, and psychological well-being.2

Benefits. The importance of a holistic approach was highlighted recently in a study funded by the National Institutes of Health about depressive disorders associated with age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The trial tested a mental health care model that was integrated into a low vision rehabilitation setting. It not only confirmed the high risk of depression associated with AMD but also showed that an integrated mental health and low vision intervention protocol halved the incidence of depression compared with standard outpatient low vision rehab. The mental health component, referred to as behavior activation, was administered by an occupational therapist specially trained in the approach. It involved helping patients to focus on activities they enjoy, to recognize that loss of those activities can lead to depression, and to reengage in those activities.6 According to Dr. Mogk, the integrated protocol used in the study corresponds to the comprehensive vision rehabilitation recommendations outlined in the Academy’s PPPs.

Nonapparent Deficits

“It’s ironic that some visual deficits can be invisible to Eye M.D.s,” Dr. Mogk said. This is particularly true for stroke patients, whose underlying cognitive and visual deficits are not always apparent in a structured eye exam. “While you may pick up on a hemianopia in a field test, you’re not going to see things like alexia [an inability to recognize letters or words] or agnosia [an inability to recognize faces or objects] until a patient is challenged functionally in a rehab evaluation,” said Annie Riddering, OTR/L, CLVT, COMS, at the Henry Ford Center for Vision Rehabilitation & Research.

Ask the patient to read some text. “If a patient mentions reading difficulties but their visual acuity is good, ask the patient to read a few sentences,” advised Dr. Mogk. “Deficits can make a dramatic appearance.”

Ask the patient to draw a clock face. Likewise, if patients (or their family members) mention driving difficulties but their vision is fine, ask the patient to draw a clock face and set the hands at ten to two, said Dr. Mogk. “I’ve been amazed by the spatial deficits this task reveals, which correlate to driving safety.”

Overall, Dr. Mogk advised ophthalmologists: “Be alert to undetected visual or cognitive deficits and to the fact that the impact of central vision loss is invisible. Patients with even advanced AMD can walk in, sit down, shake hands, appear to make eye contact, and conduct themselves as if they are fine, but they aren’t,” she said.

Practical Concerns

Who has time? In today’s private practices, many ophthalmologists simply don’t have time for lengthy discussions with patients about potential rehab. For that reason, the Academy’s SmartSight Initiative in Vision Rehabilitation created a handout for ophthalmologists to give to all patients who have any level of vision loss. The handout guides patients to local rehab providers and other resources. It’s available at www.aao.org/smartsight. “If ophthalmologists just give their patients the handout, that’s progress,” said Dr. Mogk.

Who’s paying? Many ophthalmologists, according to Dr. Jackson, are unaware that Medicare funds vision rehabilitation by occupational therapists after a referral by an ophthalmologist (or optometrist). The low vision examination is reimbursed under Evaluation and Management (E&M) codes, with the visual impairment as the primary diagnosis and the disease causing the impairment as the secondary diagnosis, added Dr. Mogk.

Driving: Realistic Expectations

Patients have varying goals and potential. Difficulties with reading and driving are the most common complaints that bring patients to rehab, according to Dr. Mogk. Setting realistic expectations is important.

Many patients want to maintain or return to driving status, which may be feasible for some. “If all a patient has is a hemianopia, there is a chance he or she can still drive, depending on the laws of the state. But if there are [other] visual or cognitive deficits as well, the likelihood is far lower,” said Ms. Riddering. To verify your state’s visual field and visual acuity requirements for driving, visit AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety or the Prevent Blindness page titled “State Vision Screening and Standards for License to Drive.”

It’s important to recognize that visual acuity alone is not an adequate measure of a patient’s ability to drive safely. For example, an adequate visual field is needed for safe driving, although there is not yet consensus on how much is enough. Drs. Jackson and Mogk highly recommend reviewing the Physician’s Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers, created by the American Medical Association and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. This is the most thorough resource currently available; it’s online and it’s free.

___________________________

FURTHER READING. See this month's “Make Your Office Safer for Patients With Low Vision” and “Caught in the Middle: The Eye M.D., Visually Impaired Drivers, and Road Safety” in the February 2010 EyeNet.

___________________________

1 Morse AR. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(2):235-237.

2 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Vision Rehabilitation: Preferred Practice Pattern. 2012. Updated May 2013. Available at www.aao.org/ppp.

3 Ivers RQ et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(1):58-64.

4 Rovner BW, Casten RJ. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(3):305-310.

5 Wang JJ et al. Med J Aust. 2001;174(6):271-275.

6 Rovner BW et al. Ophthalmology. Published online July 9, 2014.

___________________________

Mary Lou Jackson, MD, Director, Vision Rehabilitation Service, Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston. Financial disclosure: None.

Lylas G. Mogk, MD, Director, Center for Vision Rehabilitation and Research, Department of Ophthalmology, Henry Ford Health System, Grosse Pointe and Livonia, Mich. Financial disclosure: None.

Annie Riddering, OTR/L, CLVT, COMS, Director of Occupational Therapy, Center for Vision Rehabilitation and Research, Department of Ophthalmology, Henry Ford Health System, Grosse Pointe and Livonia, Mich. Financial disclosure: None.