By Samuel Baharestani, MD, Brad Kligman, BS, Tatyana Milman, MD, and Paul T. Finger, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from October 2009 and may contain outdated material.

By the age of 61, Charles Carmichael* learned to expect the worst when it came to his health. His case of uncontrolled diabetes had led to multiple complications, including proliferative diabetic retinopathy, hypertension, cataracts and a myocardial infarction. His systemic signs became so bad, in fact, that he required kidney and pancreas transplants in order to avoid renal failure and dialysis.

After the operation, Mr. Carmichael vowed to take better care of himself. He improved his diet, jogged daily and stuck to his extensive regimen of medications, including immunosuppressive drugs for the new organs. Ten years later, with his diabetes finally under control, he noticed that the hearing in his left ear was slowly deteriorating. A consultation with an otolaryngologist revealed an acoustic neuroma that was promptly treated with surgery. While he was reassured that it was a benign condition with no relation to his diabetes or medications, it was nonetheless an unnerving experience.

For the next two years Mr. Carmichael’s health remained stable until he noticed a small red growth beginning to form on the surface of his left eye. It had been slowly enlarging for about a month when he saw his primary ophthalmologist for a routine visit. With his recent history of an allegedly benign neoplasm and the fear that the growth might represent more than a simple benign process, his ophthalmologist referred him to The New York Eye Cancer Center for evaluation.

Our Initial Evaluation

Mr. Carmichael began the visit by briefing us on his past medical history and current medications, which included mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone for chronic post-transplant immunosuppression, labetalol and amlodipine for hypertension, and terazosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia.

He had no family history of eye problems or cancer. He denied any ocular pain, discharge, itchiness or change in vision.

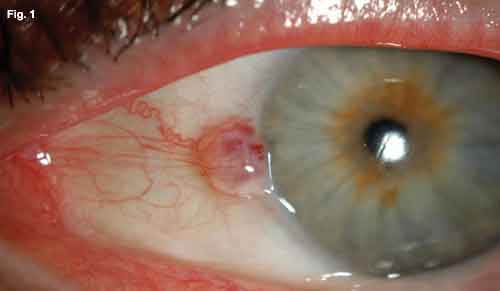

His vision was 20/50 and 20/80 in the right and left eyes, respectively. He had full range of eye movements, and there was no afferent pupillary defect. His intraocular pressures were within normal limits. Slit-lamp examination revealed a round, well-circumscribed, raised lesion on the surface of the left nasal conjunctiva, abutting the corneal limbus (Fig. 1). Although fixed to the limbus, it was mobile on gentle pressure with a cotton-tip applicator in its extralimbal regions. Feeder vessels extended from its nasal aspect. The anterior chamber was deep and quiet. There was no evidence of neovascularization, inflammation or mass effect.

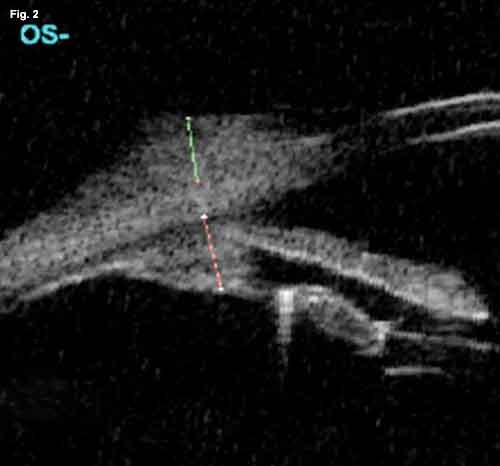

Ophthalmoscopy revealed posterior chamber intraocular lenses and laser-treated diabetic retinopathy. High-frequency 35 MHz B-scan ultrasonography (also known as ultrasound biomicroscopy) revealed a moderatelyhigh reflective epibulbar tumor with minimal scleral thinning (Fig. 2). It had a diameter of 4.9 mm and a height of 1.2 mm. There was no evidence of angle blunting or ciliary body enlargement as might be seen with tumor invasion of the globe. As a result, Mr. Carmichael underwent excisional biopsy for histopathologic diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

While we awaited the biopsy results, we considered the differential diagnosis. Our greatest concern was that this lesion represented an ocular surface squamous neoplasm. Mr. Carmichael fell within the mean age range for such disease, and the tumor’s location (abutting the limbus in the interpalpebral fissure) and vascularity were consistent with the diagnosis of a malignant tumor of the conjunctival epithelium. Furthermore, it is welldocumented that immunosupressed patients are at a significantly higher risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the eye.1 These patients are also at a higher risk for life-threatening metastatic disease.

Two additional malignancies to be concerned about in an immunosuppressed patient presenting with a conjunctival mass are Kaposi’s sarcoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The incidence of these diseases has been found to be up to nine- and threefold higher, respectively, in patients who had a kidney transplant vs. the general population.2 Although this particular lesion did not clinically resemble the classic appearance of either of those conditions, it is important to keep them in mind when dealing with an immunosuppressed patient, as they respond to particular treatment modalities and may warn of more extensive systemic disease.

Finally, amelanotic conjunctival melanoma should be considered. Although it is atypical for a melanoma to arise without preexisting primary acquired melanosis or a conjunctival nevus, there has been a 300 percent increase in conjunctival melanomas among white men over the last three decades.3

Owing to the nonspecific features of the lesion, our differential also included numerous benign conjunctival masses, such as elastotic degeneration, squamous papilloma, capillary hemangioma, reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphangioma, inclusion cyst, amyloid deposition and nodular episcleritis. Of these benign masses, conjunctival capillary hemangioma and lymphangioma appeared most plausible, given Mr. Carmichael’s clinical appearance. A conjunctival capillary hemangioma often presents as a red mass that may or may not be associated with a cutaneous or orbital capillary hemangioma. These most commonly occur in infancy but can occur in adults and often have a gradual onset and spontaneous resolution. A lymphangioma is another vascular tumor that represents dilated lymphatic channels, which often become filled with blood. These similarly can present as a pink to red solitary conjunctival mass.

We Take a Look at the Slides

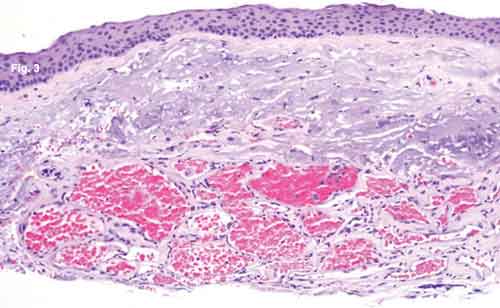

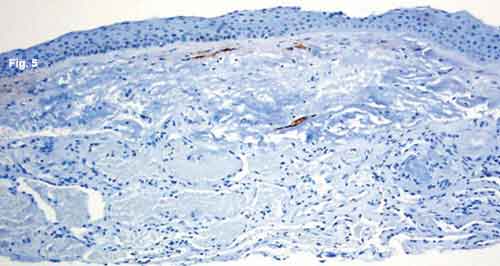

With assistance from an ophthalmic pathologist, we were reassured by a completely normal-appearing epithelium (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5). This finding ruled out some of our more worrisome potential diagnoses—conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma.

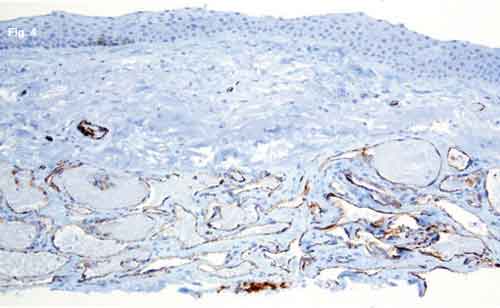

What we did discover was very unusual in a patient such as this: There was a proliferation of dilated, thinwalled, blood-filled vascular channels in the conjunctival substantia propria with an overlying area of actinic elastosis (Fig. 3). The walls of these channels stained positively for CD31 (Fig. 4), a vascular endothelial marker, and negatively with M2A immunostain (Fig. 5). M2A is an indicator for lymphatic endothelium.

These results confirmed that we were looking at a vascular proliferation without any lymphatic component. The lack of encapsulation, presence of uniformly thin septae devoid of smooth-muscle bridging, and smallcaliber vascular channels led to the diagnosis of capillary hemangioma. However, morphologically the tumor most resembled a cherry angioma (senile angioma), a subtype of capillary hemangioma that is typically recognized on the skin of elderly people, but not ordinarily noted on mucous membranes.

|

|

|

WE GET A LOOK. (Fig. 1) At the slit lamp, we note a well-circumscribed elevated lesion of the nasal conjunctiva approaching the corneal limbus. There are multiple feeder vessels with botryoid bulbs. (Fig. 2) The B-scan reveals a highly reflective epibulbar tumor (green line) with minimal scleral thinning. It measures 1.2 x 4.9 mm. There is no evidence of angle blunting or intraocular extension. The subjacent ciliary body (red line) is of normal thickness.

|

Discussion

Incidence. Two large retrospective reviews of conjunctival specimens found the occurrence of conjunctival capillary hemangioma to be 5.1 percent and 0.5 percent, respectively.4,5 When taking into account all conjunctival specimens tested rather than only those determined to be neoplasms, the rate in the first study is reduced to 0.7 percent. The same study found the mean age for diagnosis of a conjunctival capillary hemangioma to be 22.3 years of age. However, none of these reported tumors occurred in an elderly, immunosuppressed man.

Management. In Mr. Carmichael’s case, the clinical appearance of the mass, its rapid onset and the relative safety of the procedure prompted his excisional biopsy. Moreover, excisional biopsy is an acceptable treatment modality in uncomplicated cases where a hemangioma does not spontaneously regress, or the cosmetic appearance is not acceptable to the patient. Local or systemic steroids and, more recently, beta-blockers have been employed for ocular adnexal hemangiomas.6

As an alternative, cryodestruction is commonly used for a wide range of eyelid, conjunctival and scleral lesions (most commonly in conjunction with excision of the lesion).7 However, without improved imaging techniques that can provide a more definitive diagnosis without tissue sampling, excisional biopsy remains the best option for an atypical lesion that may require further cryotherapy or topical antimetabolic treatment.8

|

|

|

HISTOLOGY. (Fig. 3) There are numerous blood-filled vascular channels in the conjunctival substantia propria, with overlying actinic elastosis and normal nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. (Fig. 4) The channels stain positively for endothelial marker CD31. (Fig. 5) M2A immunostaining demonstrates that the overlying lymphatic channels appear normal.

|

Follow-Up

We recommended that Mr. Carmichael be followed with serial observation following the postop period. This included inspection of all conjunctival surfaces with lid eversion, as well as palpation of preauricular and cervical lymph nodes on all subsequent visits. To date, no tumor recurrence has been noted.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Vajdic, C. M. et al. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:1340–1342.

2 Gilbertson, D. T. and C. Wang. Am J Transplant 2004;4:905–913.

3 Yu, G. P. et al. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135:800–806.

4 Amoli, F. A. and A. B. Heidari. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006;13:275–279.

5 www.missionforvisionusa.org/anatomy/2006/06/what-is-conjunctival-hemangioma.html.

6 Siegfried, E. C. et al. N Eng J Med 2008;359:2846; author reply 2846–2847.

7 Finger, P. T. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:942–945.

8 Finger, P. T. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:807–808.

___________________________

Dr. Baharestani is an ophthalmology resident at New York University Langone Medical Center and the Manhattan Eye, Ear, and Throat Hospital. Mr. Kligman is a medical student at New York University (NYU). Dr. Milman is an assistant professor of ophthalmology and an associate attending pathologist at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary (NYEE). Dr. Finger is the director of ocular oncology at the New York Eye Cancer Center, NYEE and NYU.