Download PDF

Even though members of underrepresented minority groups make up more than 30% of the U.S. population, they make up only 6% of practicing ophthalmologists.1

And this gap matters. To begin with, clinicians with disparate backgrounds bring unique perspectives to the workforce, said Purnima S. Patel, MD, at Emory Eye Center in Atlanta. As she noted, research supports the hypothesis “that a diverse team of people comes up with more creative solutions to complex problems.”2

Moreover, within health care, diverse teams generally lead to better patient outcomes.3 For instance, minority physicians are more likely to provide care for minorities and to practice in underserved neighborhoods, said Ambar Faridi, MD, at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and the VA Portland Health Care System in Portland, Oregon. “This is especially important within ophthalmology,” she said, “given that ethnic minorities have higher rates of diabetic retinopathy, cataract, and glaucoma.” (See “Tackling Health Care Disparities,” June EyeNet.)

|

|

ROLE MODEL. Why did you become an ophthalmologist? Mentorship is key to building the pipeline of URIM candidates.

|

|

|

ZERO TOLERANCE. Discrimination and harassment need to be nipped in the bud, no matter the source—and no matter the time point in the clinician’s career.

|

How to Diversify the Pipeline

Given these challenges, how can practicing clinicians—including those who are not in academic positions—begin to redress current imbalances in the ophthalmology workforce? How can the profession broaden its outreach to URIM (underrepresented in medicine) individuals?

“Intentionality is required, not just to recruit a diverse pipeline, but also to support, retain, and promote diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) within workplaces—efforts that ultimately benefit us all,” said Dr. Patel.

Actively reach out to potential candidates—and do so early. As ophthalmology is a highly competitive surgical subspecialty, “we need to do our part to make sure that medical school students get early exposure and are set up to succeed in matching,” said Fasika A. Woreta, MD, MPH, at the Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore. Dr. Patel agreed, adding that younger students should be encouraged to pursue a career in medicine when they’re at that decision-making stage. “And when they’re deciding on a specialty, we want them to see ophthalmology as a meaningful, achievable option.”

As cochair of a new committee called CADIO (Casey Advancement of Diversity and Inclusion in Ophthalmology), Dr. Faridi works with her colleagues at OHSU’s Casey Eye Institute in outreach to high school and college minority students to tell them about a career in ophthalmology. “It’s a hidden gem that many students, especially URIM students, don’t know about,” she said. “In addition, we explain our motivations for pursuing ophthalmology to URIM students. For example, we emphasize that it is possible to change health care disparities in ophthalmology” as well as in fields like primary care and pediatrics.

Create a level playing field in medical school—and beyond. “When I was a medical student,” said Dr. Woreta, “I was told I needed board scores in the 90th percentile or above to match in ophthalmology at the programs I wanted to go to.”

In fact, said O’Rese J. Knight, MD, the first thing many mentors ask ophthalmology students is, “What is your board score?” Depending on your response, he said, “you will either be ushered into the world of ophthalmology and have every possible opportunity that a mentor can throw at you, or you will be told, ‘Thank you for playing. Please consider something else.’” Unsurprisingly, this has discouraged many students from pursuing ophthalmology, even though they may possess the requisite passion and skills, said Dr. Knight, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Help medical students gain experience and confidence. At Wilmer, said Dr. Woreta, a research elective between the first and second year of medical school provides URIM individuals with critical research and presentation experience. “At Johns Hopkins, we are having our second annual Virtual Clinical Elective in Equitable Healthcare for fourth-year URIM students applying to ophthalmology,” she said, adding that these electives also help increase recruitment. Giving students such opportunities helps give them the confidence that they can match in ophthalmology, added Dr. Patel.

Beware inequities in screening. Dr. Knight recently reviewed all ophthalmology applicant data between the years of 2016 and 2020. “The average USMLE Step 1 score of matched applicants was 245,” he said, “and [the use of] 245 as a cutoff to screen ophthalmology applications would have eliminated 75% of URIM applicants from consideration.” Thus, he noted, although using USMLE as a screening tool may not appear to support bias, “it does have a disparate racial impact.”

Technically, USMLE Step 1 “is only intended to assess minimum competency, which means if you pass, you are competent to practice medicine,” Dr. Knight said. This is one of several reasons the USMLE Composite Committee, of which Dr. Knight is a member, recently changed the scoring format of USMLE Step 1 to pass-fail. This will encourage residency selection committees to use other criteria for evaluations, he said.

Structure candidate reviews and interviews with an eye toward DEI. Dr. Faridi works with Thomas Hwang, MD, residency program director at Casey Eye Institute, to conduct a holistic review of applications and ensure that all selection committee members take training on implicit biases and approach interviews with a DEI mindset. “We are focusing more on the content of candidates’ characters, service, and scholarship than on a standardized test score, which we know contains structural racism,” she said.

It’s also important to have people on your residency selection committee who represent a broad set of views, values, and interests, said Dr. Knight. “Otherwise, it’s very easy to be impressed by applicants with a similar worldview, cultural background, or set of interests.”

Create mentorship programs—and become a mentor. If you ask current ophthalmologists why they chose the field, said Dr. Woreta, many will say it’s because of an encounter with someone who became a mentor.

Dr. Knight’s experience bears this out: As the only Black man in his University of Miami Miller School of Medicine class of 166 students, he found mentorship invaluable. “When I decided to pursue ophthalmology, I was uncomfortable because I didn’t see anyone who looked like me,” he said. “It wasn’t until a Black ophthalmologist visited my medical school and took the time to talk to—and ask about—me that it became a legitimate career choice.”

This kind of mentorship is even more important in places where no ophthalmology program exists, such as at nearly all the historically Black colleges and universities. Dr. Patel and another colleague have been serving as primary mentors at the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, which has a large percentage of URIM medical students but no ophthalmology program.

Provide substantive organizational support. Both the Academy’s Minority Ophthalmology Mentoring program4 and the Rabb-Venable Excellence in Ophthalmology Program—which Dr. Knight is a part of—have successfully supported URIM students interested in ophthalmology. “Over 20 years, Rabb-Venable has retained 90% of its participants to careers in ophthalmology,” Dr. Knight said. He added that the program has provided a “home” to him since the beginning of his medical career.

Overcoming Bias: One Doctor’s Journey

“When I was about a year old,” said Dr. Faridi, “we moved from Pakistan, where I was born, to Kuwait, where we lived until the Persian Gulf War began in 1990.” Her family escaped as refugees, living in their car for more than a month—fleeing from Kuwait to Iraq to Iran, and eventually moving back to Pakistan.

Childhood: Finding inspiration amid desperation. Faridi’s mother—who had been a pediatrician—used her medical skills to help refugees along the roadside in Iraq as the family fled the war, Dr. Faridi said. “I remember thinking how amazing it was that she could provide medical care, hope, and an empathetic ear to people who were desperate. That is when I decided to become a doctor.” During this chaotic journey, her mother experienced a retinal detachment, which also heightened the young girl’s appreciation for vision and later sparked her interest in ophthalmology.

Training: Facing bias during interviews. Faridi shared some of these experiences in her personal statement to her medical school and in her residency applications for ophthalmology. In response, some interviewers asked her pointed questions about the situation in the Middle East (e.g., “How would you fix the problem with the Taliban?”). At a program in the Midwest, the interviewer’s first question was, “Why would someone like you want to come here?”

These questions, she said, made her feel uncomfortable and negatively stereotyped rather than valued as an individual with unique skills and talents.

Fortunately, she said, she felt supported and guided by her “wonderful ophthalmology advisors”—and she noted that the experience illustrates “the critical need for the early mentorship of students entering our field.” And now that she is involved in the residency selection process herself, she emphasizes the importance of identifying one’s biases and checking them daily, participating in unconscious bias training regularly, and taking implicit association tests through Project Implicit (https://implicit.harvard.edu).

Practice: Dealing with microaggressions. Fast-forward to today: Dr. Faridi’s “everyday experiences as a Brown, Asian woman” in ophthalmology include navigating discourteous comments and questions from patients, such as, “You speak perfect English, no accent!” or “You look so exotic; where are you from?” Her response: “I’m American, and let’s get back to your medical visit.” Her colleagues from other specialties and institutions have shared similar experiences with her, she said. “We strive to provide excellent patient care, but if we feel uncomfortable, that is hard.”

Tools for responding to all kinds of bias and microaggressions range from simply not acknowledging the incident to standing up for yourself or for someone else, said Dr. Faridi. “As I’ve gotten more established in my career, I’ve started to do the latter more and more. I’ve also learned how important it is to be an active ally and bystander, and I encourage everyone to seek out bystander training—and to take it!”

|

Beyond Recruitment: Build for the Future

Is the solution to simply hire from diverse groups? On one hand, that would seem to be the case, especially when confronted with the challenges of uprooting deeply entrenched cultural biases.

But such hiring efforts appear to be falling short: A survey of 16,000 employees in 14 countries found that three-quarters of underrepresented groups don’t feel as though they’ve personally benefited from DEI programs.5 What’s missing?

A diverse leadership. Visible role models speak volumes. And although DEI efforts need to take place across the board, a diverse leadership can supercharge change, said Dr. Patel. As an example, Dr. Faridi cited Danny Jacobs, MD, the first Black president of OHSU. “Under his leadership, I’ve seen more antiracist initiatives than ever before—ones that predated the summer of 2020.”

According to Dr. Woreta, diverse leadership also helps with recruitment and retention of top URIM candidates, who often will ask about a program’s DEI efforts. In fact, she said, the schools that are doing well with recruitment all have a diverse leadership and have been great diversity advocates.

However, as Dr. Knight cautioned, this can’t be a “one-and-done” tactic. “Increasing the pool of available candidates who can be promoted into leadership will continue to require very intentional and active recruitment” by gatekeepers, he said.

A planned, intentional approach. Dr. Woreta recommends mandatory cultural competency and implicit bias training, especially for everyone involved in selection committees, whether for residency and medical school, fellowships, or faculty.

But such efforts take thoughtful planning and development. In other words, don’t simply show videos and leave it at that, Dr. Patel said. “Include intentional discussions to ensure people understand the effects of implicit bias, and make infrastructural changes to decrease its impact.”

To support these efforts in ophthalmology, the Academy has formed special task forces and is revising Section 1 of the Basic Clinical and Science Course to include a new chapter on Social Determinants of Health (see “Key DEI Resource”). “Educating ophthalmologists and ophthalmologists in training about DEI is essential for turning awareness into action,” said Dr. Faridi.

Key DEI Resource

The Academy continues to expand and update the resources on its DEI web page (aao.org/diversity-equity-and-inclusion). It now includes the following:

- An extensive list of citations, including journals and books.

- Links to webinars, videos, and podcasts.

- A section on the Minority Ophthalmology Mentoring Program (see aao.org/minority-mentoring).

- A link to Chapter 17 of BCSC Section 1, Update on General Medicine. This chapter, Social Determinants of Health, will appear in the 2022-2023 edition and will be expanded for the 2023-2024 edition.

|

Reality Check: Be Prepared

Share the load—and beware any DEI stigma. “It’s a huge effort to make all of this happen,” said Dr. Patel. “The work of learning, educating, and removing institutional barriers is up to everyone. This can’t just be a volunteer effort by URIMs.” If it is, it can turn into a kind of “minority tax.”

And despite the benefits of URIM-concordant mentors, said Dr. Knight, relying solely on them adds a professional burden—one that’s unpaid and often unrecognized and unappreciated.

“URIM faculty feel obligated to the groups they represent and spend more time on DEI projects, but they are disproportionately represented in institutions’ diversity efforts,” said Dr. Faridi. “Does this leave them time to work on other ‘more valued and awarded’ projects? We need to end the ‘diversity efforts disparity’ by supporting our URIM colleagues and sharing the time-consuming, heavy load of this work. This will help us promote and retain them as well.”

Take a proactive stance. Well-designed antidiscrimination policies, publications, and training need to be available before problems occur, said Dr. Patel.

“Leadership needs to really embrace zero tolerance for any kind of discrimination or harassment—even when it’s coming from a patient. We need to serve as advocates for our medical students, residents, and fellows during a vulnerable part of their career,” said Dr. Woreta.

The most important thing is to keep an open mind and listen to colleagues who have experienced discrimination, said Chris Albanis, MD, with Ocular Partners and Arbor Centers for EyeCare in the Chicago area. “It can be eye-opening because many people think these things don’t happen anymore.”

Have a plan. Dr. Albanis said that leaders can help by taking the following steps:

- Establish trust and allay any concerns about retaliation.

- Take charges seriously and be thoughtful with comments.

- Ensure privacy but thoroughly document the conversation.

- Take action (including disciplinary, if indicated), bringing complaints to human resources sooner rather than later, especially if there is a legal or compliance issue.

- Follow up to make sure concerns are resolved.

- Educate, coach, listen, and re-educate.

Address barriers. It’s important not to underestimate the obstacles for URIM individuals. For example, a few years ago, women ophthalmologists vocalized concerns about the lack of lactation facilities at the Academy’s annual meeting, said Dr. Patel. “It was difficult for lactating moms to attend the meeting, so they missed out on opportunities to present, collaborate, and network.” The Academy addressed this barrier, she said, which not only allows women to share their talents at the Academy’s meeting but also may lead to similar improvements at other meetings.

Be aware of cultural disconnects. One source of bias in medicine stems from cultural differences, which can lead to subjective clinical evaluations. For instance, Dr. Knight was a first-generation college student who grew up in a Caribbean household. He describes how clinical attendings initially questioned his ability to be a “team player”—though, by the end of the rotation, they were well aware of his ability to care for patients.

Without a shared cultural identity, he explained, he may have initially appeared aloof when he couldn’t add to certain conversations about music, food, books, or television shows. In a competitive environment, he added, such subjective evaluations significantly influence whether an individual is considered for opportunities and advancement.

Promote cultural connections. Making an effort to connect outside of the daily work routine is one way to get to know each other as unique people.

To help promote cultural awareness within her organization, Dr. Albanis has responded to various staff members’ requests to celebrate Black History Month, the Day of the Dead, and Ramadan. Last year, staff celebrated a variety of cultures and traditions during a Zoom holiday party. It’s important to make staff feel comfortable suggesting such celebrations, she emphasized—and she added that it’s also critical to reach out to multiple staff members to help shape these programs, instead of tapping the person who typically writes policies and procedures.

Follow the Data

Evidence of inequity abounds. Consider the following:

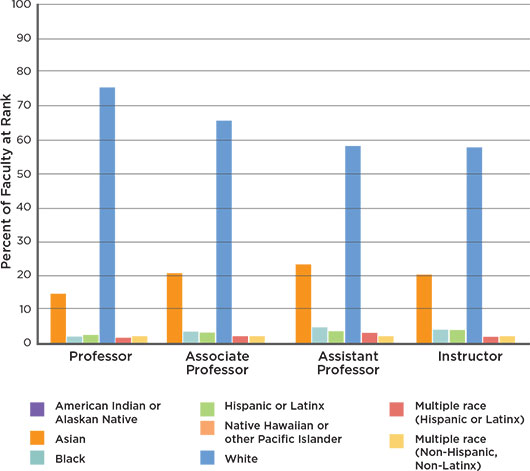

In faculty positions. When compared to their peers, URIM individuals are more often in junior faculty than in leadership positions, are promoted at lower rates, and experience disparities in compensation.1 And clinical faculty and department chairs of ophthalmology at United States medical schools are the third least diverse of 18 clinical departments across the country.2,3 For instance, in 2015, Blacks made up 2% of ophthalmology faculty, with Hispanics making up 3.4%.3

In practice. While there was a modest increase in the proportion of female practicing ophthalmologists from 2005 to 2015 (23.8% to 27.1%), there was no increase in URIM ophthalmologists during the same time period (7.2% over time).3

Research, diversity, and disparity. Health disparities researchers and minority faculty who spearhead DEI initiatives often don’t get the same credit for their efforts as someone who created a surgical teaching course.4

Research, publication, and leadership. In a study of 1,077 journal editorial and professional society board members, 74% were men and 26% were women; 92.3% of editors-in-chief or presidents were men and 7.7% were women. No association was seen between publication productivity and election to leadership positions.5

WIDESPREAD CHALLENGE. U.S. medical school faculty, as of Dec. 31, 2020. Adapted from Rotenstein LS et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1083-1086.

___________________________

1 Rodriguez JE et al. BMC Medical Educ. 2015;15:6.

2 Fairless EA et al. Ophthalmology. Published online Jan. 10, 2021.

3 Xierali IM et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(9):1016-1023.

4 Hoppe TA et al. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaaw7238.

5 Camacci ML et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(5):451-458.

|

Can We Measure Success?

Given the impact of health care disparities on patient health, it is essential that ophthalmology conduct the kind of research that’s been done by other specialties to identify health care “deserts” for underserved groups of patients, said Dr. Knight.

Nationwide metrics also are important to see how well the profession is doing with DEI, said Dr. Woreta. Until relatively recently, ophthalmology wasn’t properly measuring its success, said Dr. Patel, but data such as those from the Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology are now available.6

Monitoring metrics for diversity will help ophthalmologists realize where improvement is needed, said Dr. Woreta. “Sharing diversity efforts across specialties and programs throughout the country will help program directors learn from each other and gain new ideas about how to increase DEI.”

Eyes on the prize. “In our profession, of course, data are important,” said Dr. Albanis. “But much of this is a cultural shift that can’t be easily measured with numbers. We need to stop and listen to ourselves and each other and ask, ‘Are we actually getting where we need to go?’”

Whether it’s creating evaluation guidelines free of bias, roadmaps for advancement, time and funding for training, or grants for URIM faculty, the time for action is past due, Dr. Knight said. He added that, as a community, ophthalmology should strive to ensure that all ophthalmologists—whether in academic or private practice—have access to the same professional opportunities. That means “the same ability to earn, to pursue research interests, to present at national conferences, and to serve in leadership roles in our professional societies. Anything less falls short.”

___________________________

1 Xierali IM et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(9):1016-1023.

2 Tsusaka M et al. www.bcg.com/publications/2019/winning-the-20s-business-imperative-of-diversity. Published June 20, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2021.

3 Gomez LE, Bernet P. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(4):383-392.

4 Aguwa UT et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;223:306-307.

5 Krentz M et al. www.bcg.com/publications/2019/fixing-the-flawed-approach-to-diversity. Published Jan. 17, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2021.

6 https://aupo.org/news/2019-03/gender-and-ethnicity-data-ophthalmology-residency-2019. Published March 9, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2021.

Meet the Experts

CHRIS ALBANIS, MD Chief medical officer of Ocular Partners, president of Arbor Centers for EyeCare, and chair of ophthalmology at Advocate Christ Medical Center, all in the greater Chicago area. She is also clinical associate of ophthalmology at the University of Chicago and serves as the Academy’s Leadership Development Program director. Financial disclosures: None.

AMBAR FARIDI, MD Ophthalmologist with the VA Portland Health Care System and associate professor of ophthalmology and associate residency program director at Oregon Health & Science University, both in Portland. Financial disclosures: None.

O’RESE J. KNIGHT, MD Associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill. He is also a member of the Diversity and Inclusion Council at UNC’s School of Medicine. Financial disclosures: None.

PURNIMA S. PATEL, MD Ophthalmologist with the Emory Eye Center and Atlanta VA Medical Center in Atlanta. She is also associate professor of ophthalmology at the Emory University School of Medicine. Financial disclosures: None.

FASIKA A. WORETA, MD, MPH Assistant professor of ophthalmology and residency program director at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of the Eye Trauma Center at the Wilmer Eye Institute, both in Baltimore. Financial disclosures: None.

More at AAO 2021

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Retina (event code Ret03). When: Friday, 9:36-9:42 a.m. Where: The Great Hall.

Diversity Task Force Researching Eye Health Care Equity Amidst Workforce Disparity (Sym23). When: Sunday, 11:30 a.m.-12:45 p.m. Where: New Orleans Theater C.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: Perspectives From Ophthalmology Leadership (Sym39). When: Monday, 11:30 a.m.-12:45 p.m. Where: Room 243.

Achieving Health Equity in Glaucoma Care (Sym42). When: Monday, 2:00-3:15 p.m. Where: Room 243.

|